Data-based Discussion on Education and Children in Japan

- 1. Bukatsudou--A Puzzling Activity that Most Students Join

- 2. Analyzing Juku--Another School After School

- 3. Low Self-Esteem Among Japanese Children--How to Overcome This Issue

- 4. Issues Regarding Japanese Children's Reading--In Association with the Effects of Reading

- 5. Now's the time amid COVID-19 fear, let's close up on the positive side of a "well-regulated lifestyle"

- 6. To prevent the "cycle of poverty" -current situation in Japan concerning continuation of education to college (This paper)

The issue of "Poverty" in Japan

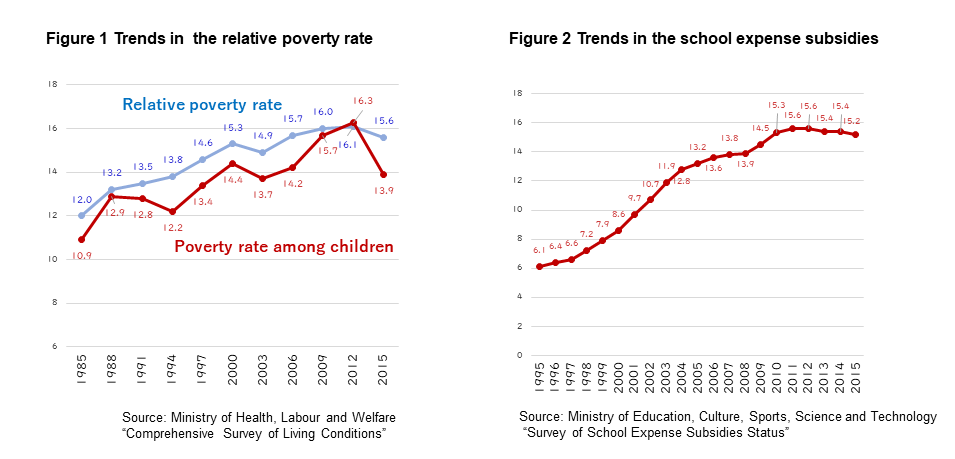

In 2014, the Japanese people were confronted with the shocking news that one in six children were living in poverty. In that year, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced that 16.3% of children under the age of 18 lived in households whose income ranked below half of the median household income, which was the worst record in history (Figure 1). This figure later improved to 13.9% according to research conducted in 2015, but it still remains at a high level, putting Japan among the high poverty rate nations of OECD members.

Japan has been called as a society of "all Japanese belong to the middle class." The dominant sentiment is that most Japanese people live above a certain standard of living, even though there are few very rich people. In the "Public Opinion Survey on the Life of the People" conducted by the Cabinet Office, 90% of the respondents rated their living standard as "middle class." This trend has remained unchanged from the 1960s until the present. In our daily lives, we do not see people who are very poor, without housing or food. Therefore, we are stunned at the revelation that the number of children living in poverty is increasing without our knowledge.

However, the signs were already making an appearance, and schoolteachers became aware that families in financial difficulty were increasing in number. That was shown by the increase in the number of children receiving school expense subsidies. Since the latter half of the 1990s, there has been a large increase in the number of children eligible for school expense subsidies. Before 2000, the proportion of children who qualified for and received school expense subsidies due to low family income was less than 8%, while it almost doubled to 15.6% in 2012 (Figure 2). This almost matches the result of the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions introduced at the beginning. Theoretically, around six children in a class of 40 are applicable.

Researchers have also revealed that the "education gap" comes about due to economic conditions and the cultural background of families. Traditionally it was considered in Japan that the gap between the rich and the poor would diminish due to equal distribution of good quality education. Many Japanese shared the belief that even a poor child could become successful in society if he/she performed well in schools by applying his/her ability and effort.

However, research in the 2000s eradicated such belief. In educational sociology research, my expertise, it has been revealed that gaps exist in the performance of children at school or their later education in colleges. Depending on the economic circumstances and culture of their families, a class difference exists in their motivation toward social success. Moreover, it has been proved that this gap has been widening in recent years*1. What is indicated is a larger possibility that the effect of school education is to reproduce and enlarge the gap between rich and poor (gap enlarging function) rather than to have a shrinking effect (equalizing function). It is comparatively easy for children of affluent families to maintain or improve their position through education, while poor families are unable to give sufficient education to their children. As a result, the gap tends to widen.

The government has not been inactive in this situation. In 2013, the "Law on Measures to Counter Child Poverty" was unanimously passed in both Houses of the Diet. In 2014, the "General Rule on Measures to Child Poverty" was approved by Cabinet decision. In the General Rule, it is clearly written that the indices concerning child poverty are established in specific terms, and the ministries and agencies in charge cooperate to comprehensively promote the measures. Various viewpoints to correct the gap were included such as guaranteeing academic ability, reducing the burden of educational expenses, support for living and recruitment of guardians, and financial assistance. Furthermore, the "Law to Support Education in Colleges and Other Institutions" was passed in May 2019, providing low income families with exemption/reduction of tuition and offering scholarships.

Gap in continuing education into college

Such efforts should be continued, however, they are insufficient to solve the current problems, one of which is the gap in continuing education into college.

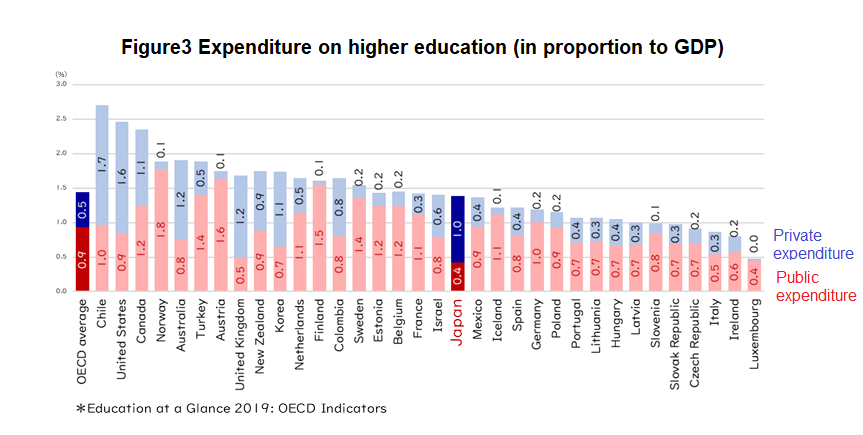

In Japan, the high cost of higher education discourages children in poverty from going on to receive college education. Figure 3 shows the ratio of higher education bearers in proportion to GDP in each country. This indicates Japan is positioned in the middle among OECD countries for expenditure on higher education. However, a large amount is paid privately while public expenditure stays low. Public expenditure in proportion to GDP is at the lowest level. The government simply does not spend sufficient money.

This means that the burden weighs heavily on families. It is not rare to see the expense of higher education exceeding 10 million yen when the cumulative expense concerning preparation for college is added, plus housing and living expenses away from family, etc., on top of enrollment fees and college tuition. If there is more than one child in a family, the burden weighs even heavier. When asked the reason why couples do not realize their ideal number of children, many couples answered "It costs too much to raise and educate children" ("Japanese National Fertility Survey" by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research). It is widely recognized that education costs too much.

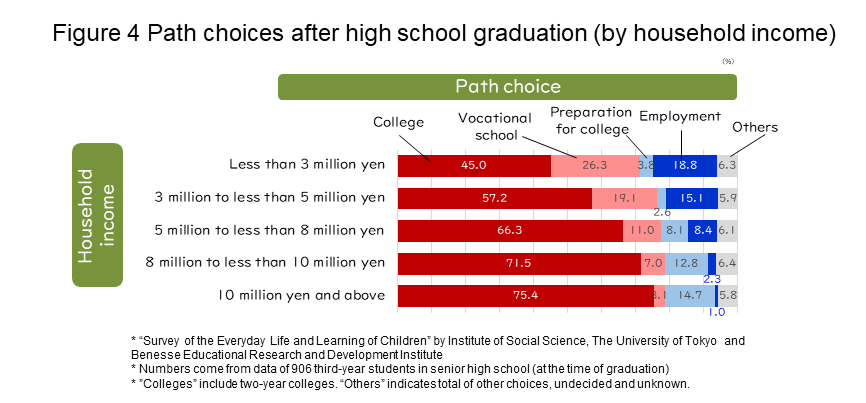

Let us see the difference in the ratio of continuing education in colleges by household income. Figure 4 shows the result of a survey asking third-year senior high school students what they would do after graduation, divided by household income. In Japan, somewhat fewer than 60% of students go on to colleges or two-year colleges, so caution is necessary in that the population of this research includes more than the average response for higher education. Still, it is obvious that household income affects the difference in the path choices after graduation. The lower the household income, the more students choose "vocational school" or "employment," while the higher the income, the more students choose "college" or "preparation for college." The total of responses for "college" and academic "preparation for college" exceeds 90% among households whose income is "10 million yen and above," while it is lower than 50% in households whose income is "less than 3 million yen." Children of low-income families have relatively fewer opportunities to receive higher education. It should be added that children of higher income families tend to go to topnotch schools among those who go on to colleges. For example, "Survey of Living condition of Students" conducted by The University of Tokyo clearly shows a deviation in the household income of students' families toward higher class. The tuition fees of national universities should be affordable, but that does not mean students from low-income families are enrolled.

Problem of family environment in the background

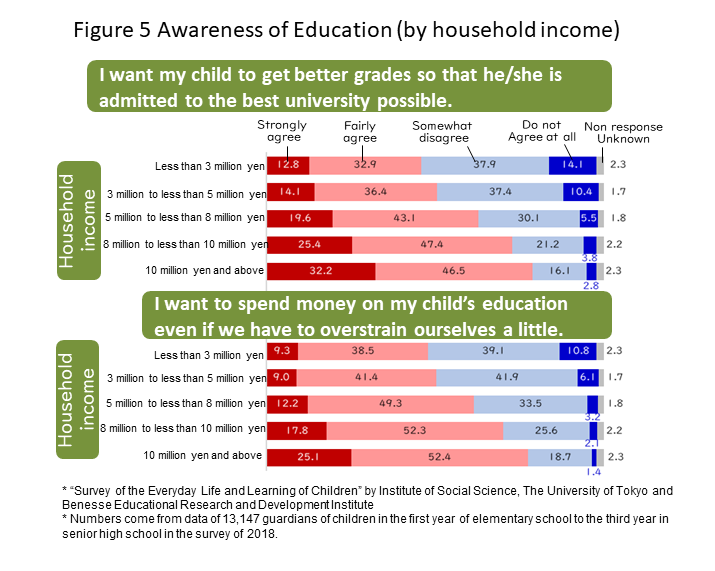

This problem is difficult to solve because the simple economic factor is not the only thing that decides continuing education in colleges. Even if college education became completely free of charge, the gap in the opportunities for college education by household income would probably remain. That is because differences exist in the cultural environment among families. First, parents (guardians) in high-income households tend to be highly educated. Such parents have a high affinity with school culture, and well understand the value of education received in schools and good grades. Figure 5 shows this aspect.

The graph on the top in Figure 5 shows the response to the statement "I want my child to get better grades so that he/she is admitted to the best university possible."

You can see that the lower the annual income of the parents, the more negative the response, while positive responses increase as income becomes higher. Similarly, the bottom graphs show the responses to the statement "I want to spend money on education for my child even if we have to overstrain ourselves a little." Again, the households with higher income give more positive responses.

As you can see, household income and awareness of education are correlated, which is reflected in actual behavior. Seen relatively, the low-income class contains more parents who are not enthusiastic about education. They tend to show passive behavior in educational encouragement to their children or educational investment outside schools. As a result, their children are less able to be motivated for continuing education in colleges. They avoid study, let their grades drop, and make choices other than going on to colleges.

Should be viewed as a structural problem

When considering the relationship between the socio-economic status of parents and choice of career path by children, "Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs" by Paul E. Willis is a good source of reference. This research was conducted in the UK in the 1970s under the important theme of class reproduction through school education.

This pioneering research reveals that there is a paradoxical structure of existing social system reproduction by children of the labourer class denying school education (meaning middle-class culture). It should be noted that being one of the "lads" involves actively choosing to fall off from the system and not receive college education. Their choice lands them a job in factories (workplace resembling prison cells without freedom) and ultimately absorbed into the social system. Only "education" can set them free from the prison, but it is too late by the time they realize that.

In Japan, class division is not that obvious and cultural clash is not apparent. This point shows a palpable difference from the situation in the UK depicted by Willis. Also, opportunities for college education are given equally to high school graduates (or those with equivalent education). It appears to be equality of opportunity. This presents all the more reasons for the children themselves and people around them to conclude it was the results of their own choices that children in poverty did not go on to study in colleges. However, it may be due to the mechanism that leads them "not to choose colleges" - the mechanism that prevents the introduction of the value of higher education and cools their motivation for studying.

We should not only blame the children for being responsible for their choice but also look at this problem as a structural one, where family environment and school education are making an impact in complex ways. We also need extra consideration for children in poverty to prevent school education from enhancing the problem. It also brings huge merit to society to teach them that education is one of the ways to get out of the prison called poverty.

Breaking the cycle of poverty

Japan has a problem of productivity too slow to be improved in addition to its rapidly aging society. We cannot maintain our national strength in this way. Some developed countries suffer from similar problems. It is considered important to continuously support childbirth and child rearing (and work-style support along with it) as well as enrichment of education. The cycle of poverty works negatively on both of those.

The current situation of an increasing poverty rate among children was introduced at the beginning of this paper. If unattended, a further declining birthrate and social inactivity will result. First, it will be difficult for people in poverty to get married, have children and raise them. Also, in a situation where the gap is reproduced through education, the class who feel they are not receiving the merit of education will be reluctant to actively receive education. It is thought to be the cause of lower productivity throughout the whole of society and result in higher cost of social security, etc.

Breaking the cycle of poverty will lead to the creation of a society where success gained by ability and effort is justly rewarded, not success bestowed by birth. This is an ideal principle in modern society. Are we getting near to the ideal? I think it is about time we, not only in Japan but also all countries and regions, everyone, should take it seriously and deal with this problem beyond our borders.

- *1 Takehiko Kariya, (2011). Kaisouka nippon to kyouikukiki -fubyoudousaiseisan kara iyoku kakusa shakai (insentibu dibaido)[Class divided Japan and Educational Crisis - from Reproducing Inequality to Motivation Gap Society (Incentive Divide)] Yushindo.

Haruo Kimura

Haruo Kimura