Data-based Discussion on Education and Children in Japan

- 1. Bukatsudou--A Puzzling Activity that Most Students Join

- 2. Analyzing Juku--Another School After School (This paper)

- 3. Low Self-Esteem Among Japanese Children--How to Overcome This Issue

- 4. Issues Regarding Japanese Children's Reading--In Association with the Effects of Reading

- 5. Now's the time amid COVID-19 fear, let's close up on the positive side of a "well-regulated lifestyle"

- 6. To prevent the "cycle of poverty" -current situation in Japan concerning continuation of education to college

We bring you the second issue of our series introducing the landscape of education in Japan using data. This issue focuses on juku--private supplementary tutoring classes which many children attend after school.

Such tutoring is common not only in Japan but also in many other countries, particularly in Asia. According to "Basic Research on Academic Performance - International Survey of Six Cities" in which the author took part in the survey team, the juku enrollment rate among 5th grade elementary school students subject to the survey was 51.6%, 72.9% and 76.6% in Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing respectively. Jukus can be found all over urban areas in Asia, portraying the astonishing fervor for education. Mark Bray named such private supplementary tutoring "shadow education" since it was obscured under the shadow of public education up till now, and at times, even criticized. Recently, however, light is being shed on this "shadow education" as a research subject (e.g., Mark Bray, 1999, The Shadow Education System: Private Tutoring and its Implications for Planners). The role and function that private supplementary tutoring plays in each country is a highly significant research topic.

How many children attend juku in Japan? And how does this relate to the Japanese educational system and juken (i.e., taking entrance exams for lower/upper secondary school or university)? Are there any issues in this realm? We examine the current situation of Japan's education from the aspect of juku, which can be regarded as another school after school.

Juku Enrollment Rate by Grade

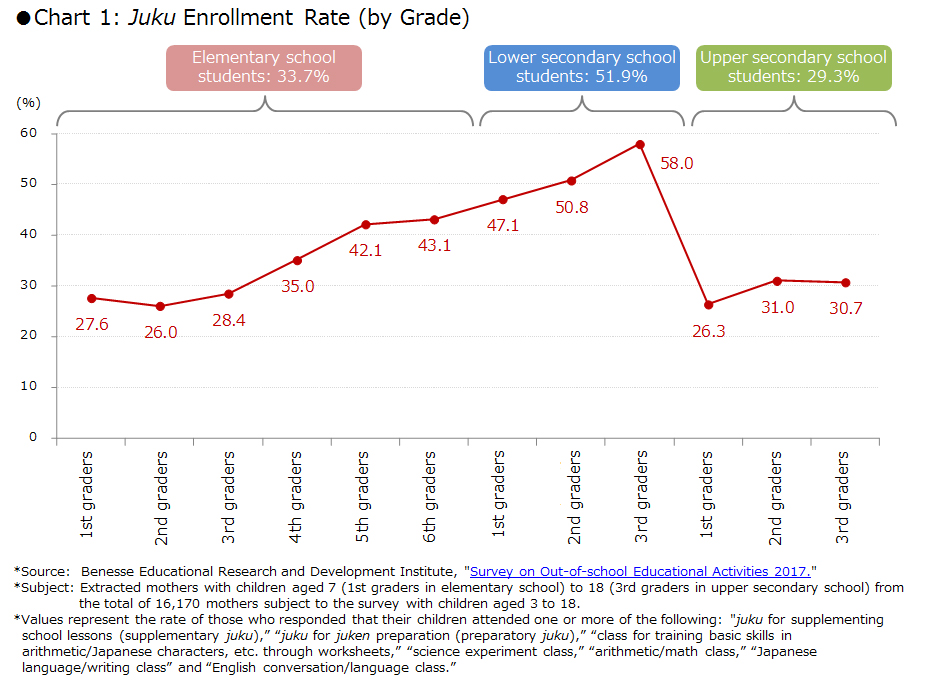

For starters, how common is it for children to attend juku in Japan? Chart 1 shows the juku enrollment rate by grade revealed in "Survey on Out-of-school Educational Activities 2017 (in Japanese)." In the survey, 16,000 mothers were asked whether their children attended juku during the past year. Several implications can be drawn from this survey.

Firstly, for elementary school students as a whole, the average juku enrollment rate is just over 30%, but increases incrementally from 2nd to 6th grade.

Secondly, in lower secondary school, the rate continues to rise, peaking at 58.0% in 3rd grade. More than half of the lower secondary students attend juku.

Thirdly, in upper secondary school, the rate declines markedly in 1st grade and hovers around 30% thereafter, suggesting that not a lot of students attend juku.

In short, lower secondary school students have the highest juku enrollment rate in Japan. This is due to factors related to Japan's education system, and entrance examination and admission system. Below, we consider why students of each school stage attend juku.

Elementary School Students and Juku

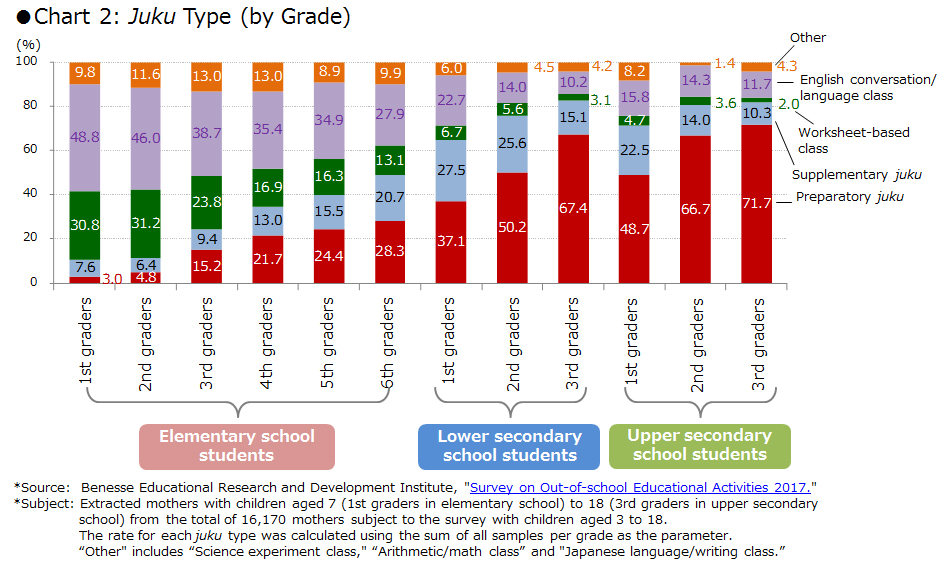

First, let us examine juku enrollment among elementary school students. Chart 2 extracts those subject to the survey that attended juku, and tabulates those samples by the type of juku.

The chart reveals that during the early stage of elementary school (1st to 3rd grade), few attend "Preparatory juku (i.e., juku for juken preparation)" and "Supplementary juku (i.e., juku for supplementing school lessons)," while many attend "English conversation/language classes" and "Worksheet-based classes (i.e., class for training basic skills in arithmetic/Japanese characters, etc. through worksheets, e.g., Kumon method)." This suggests that raising basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic, or skills in English are prioritized over raising academic performance in specific subjects, which is what "Preparatory juku" and "Supplementary juku" cater to. At this stage, many children also take part in out-of-school activities other than juku shown in Chart 2, such as sports, music or arts, suggesting that many parents want their children to gain wide-ranging experiences aside from studying.

However, the situation changes slightly during the latter stage of elementary school (4th to 6th grade). While the rate for "English conversation/language class" and "Worksheet-based class" declines, the rate for "Preparatory juku" rises to 20-30%. Since the overall juku enrollment rate for 4th to 6th grade students is some 40% (Chart 1), this means that 10% of all children attend "Preparatory juku." The main factor for this change is juken for lower secondary school.

Over 90% of children in Japan enroll in local, public lower secondary schools which do not require taking entrance examinations, or juken. Meanwhile, some 8% go to private lower secondary schools requiring juken, for which students generally need to start preparing from 4th grade.

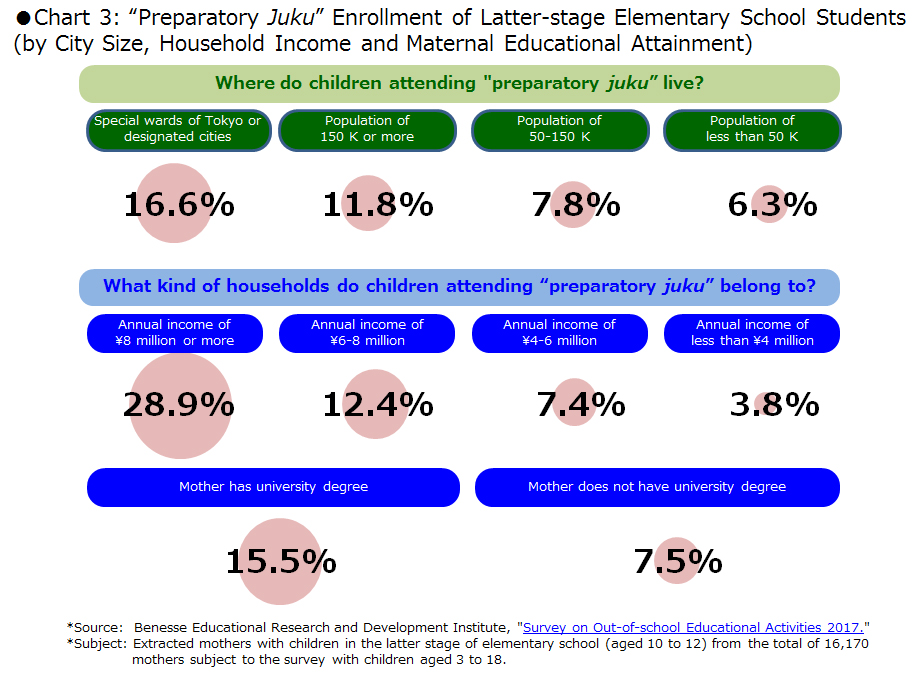

Such juken is concentrated in urban areas. In Tokyo, 26% of children enroll in private lower secondary schools, but this rate is zero in some other areas. Major providers of preparatory juku therefore tend to offer their classes in urban areas, while children in rural areas do not have the option to attend such type of juku.

In that sense, "inequality" can be regarded as a key issue in juku enrollment among elementary school students--in particular, for preparatory juku targeting lower secondary school juken. One "inequality" is that between urban/rural regions as mentioned, and another is that between households. Higher-income households have an advantage, since preparing for juken and enrolling in private lower secondary schools is considerably costly. In addition, highly educated parents with strong interest in education tend to make their children undertake juken. From an analysis based on this perspective, a bias can be detected in different attributes of those attending preparatory juku (Chart 3). In short, in terms of juku enrollment for elementary school students, there is overheated competition to enter private lower secondary schools for some groups.

Lower Secondary School Students and Juku

Next, we examine juku enrollment among lower secondary school students. Chart 1 shows that the juku enrollment rate increases from 47.1% in 1st grade, to 50.8% in 2nd grade, and 58.0% in 3rd grade. Also, the breakdown by juku type shown in Chart 2 indicates that the rate for "English conversation/language class" declines while the rate for "Preparatory juku" increases.

In Japan, the upper secondary school advancement rate is 98.8%, with almost all students taking part in the juken competition, unlike for lower secondary school or university. Additionally, entrance exams for public upper secondary schools are highly unique depending on prefecture. Jukus excel in providing customized strategies for entrance exams of each region.

Another factor prompting juku enrollment is schools' lack of information concerning upper secondary school juken. Previously, the competition for juken was intense and schools intently provided guidance. However, to suppress the overheating of juken guidance, the Ministry of Education at that time notified schools to refrain from using mock exams provided by private education service providers in the early 1990s. As a result, schools could no longer determine whether their students would pass the exam for the school of their choice, ironically driving students to attend juku.

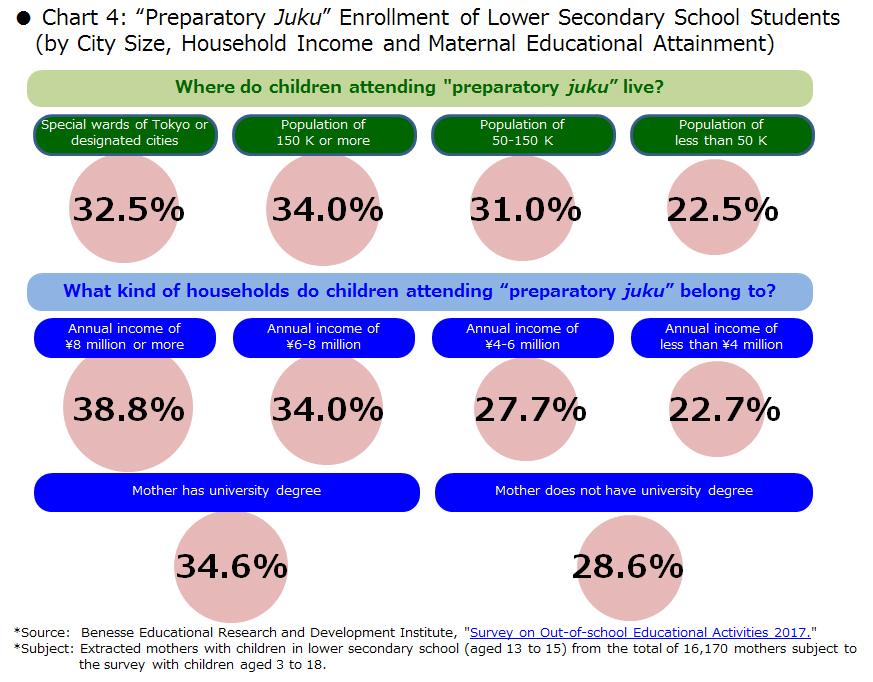

As mentioned, almost all students take part in juken for upper secondary school. To corroborate this, there is no bias in the juku enrollment rate among lower secondary school students with different attributes, unlike in the case of elementary school students. Results of the analysis are shown in Chart 4. In summary, the number of children who attend preparatory juku increases during lower secondary school because of juken for upper secondary school which almost all students take part in.

Upper Secondary School Students and Juku

How does the situation change in upper secondary school? The juku enrollment rate falls to 26.3% in 1st grade and does not increase much thereafter, hovering around 30% during 2nd and 3rd grade. There are several reasons for this decline.

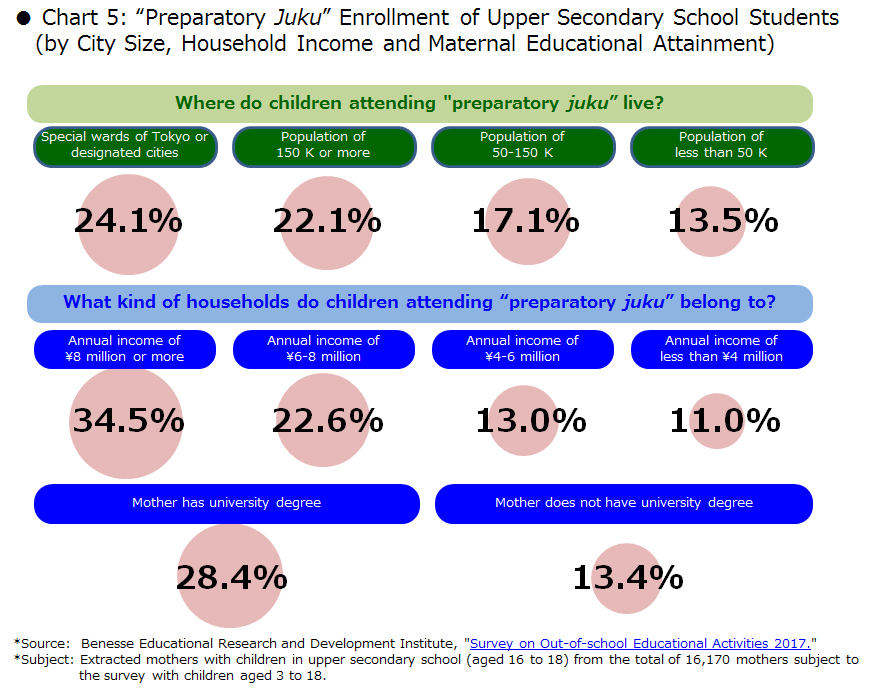

One is that not all students take part in the competition to enter university. The advancement rate for university and college was 57.3% in 2017. In addition, from a longer-term perspective, the 18-year-old population is shrinking while the number of universities is increasing. The ratio of applicants per place which was 2 fold or more during the 1970s is currently about 1.1 fold. One can go so far as to say that students can enter university without studying, as long as they are not selective in their choice of university. Admittedly, it is still difficult to enter top ranking universities and competition does exist for certain groups; however, not all students are involved in this competition. As shown in Chart 5, children of urban households with higher income and educational attainment tend to attend juku, whereas children of households with lower income and educational attainment tend not to, suggesting that there is inequality at this stage as well.

Another reason for the decline in juku enrollment is that upper secondary schools are sufficiently able to provide guidance for university juken. Upper secondary schools in Japan are diverse, unlike lower secondary schools, since juken for upper secondary schools sort students by academic performance. In some schools, many graduates enroll in university, while in others, many find employment or enroll in vocational schools. Also, even among schools where most graduates enroll in university, the contents of juken guidance differ depending on whether students enroll in top-ranking universities or middle-ranking ones. Since each upper secondary school provides education tailored to their students' education track and aims for superior university advancement rates, juken preparation can be handled sufficiently within the scope of each school. This is largely different from elementary or lower secondary schools where juken preparation is mostly covered by juku.

That said, the relationship between upper secondary schools and juku seems to be changing. The longitudinal data of "Basic Research on Academic Performance in Japan (in Japanese)" which surveys the academic activities of children, shows that the juku enrollment rate is rising only among upper secondary school students. More specifically, the juku enrollment rate for 2nd grade upper secondary school students subject to the research increased from 12.7% in 1990 to 15.0% in 1996, 19.8% in 2001, 25.3% in 2006, and 27.2% in 2015.

This is partially owing to the fact that students previously had to attend actual juku classrooms, whereas, now, they can view classes of distinguished teachers anywhere and at any time through videos or online streaming. More and more jukus are providing such audio-visual classes throughout Japan.

In addition, now that it is easier to enter university, there are less students who fail juken and study another year at juku in preparation for the following year. These students are called rouninsei, and have been a specific target group for juku industries. In response to the contraction in customer base, jukus have been expanding services targeting upper secondary school students--another reason why juku has become more accessible to upper secondary school students. Students nowadays expect jukus to provide thorough guidance catered to one's needs. Along with the diversification of university entrance exams, jukus are now taking over needs that cannot be covered by schools.

The Future of Juku

We elaborated on the current situation of jukus by school stage thus far. In closing, I would like to comment briefly on current challenges as well as the future prospect of juku.

I feel that the social position of juku has been rising in Japan. Juku used to be considered a necessary evil fuelling the juken competition and distorting "the ideal education;" however, this is not the case today. Rather, the society expects, and at times, even relies on jukus to make up for shortfalls of public education. Currently, various demands are being made from society to school education. To respond to such demands, there is momentum among the public education sector to seek help from the private education sector. I believe this is partially owing to efforts on the part of private education service providers to offer more valuable learning opportunities.

Meanwhile, jukus also inherently function to widen social disparity and inequality. For example, about half of those entering The University of Tokyo, which is regarded as Japan's top university, are graduates of private, integrated (lower and upper) secondary schools. To enter such schools, children must attend juku during elementary school, making it advantageous for children of urban households with higher income and educational attainment. Jukus cannot simply be dismissed when considering its strength in fostering each child's capabilities. Yet, when looking at society as a whole, one must acknowledge that children who cannot attend juku may be deprived of the opportunity to unleash their full potential.

In addition, jukus emphasize short-term outcomes, which is inevitable in some ways since that is what their customers seek. However, in the world of education, there are many important things that do not yield immediate outcomes. Going forward, the private education sector needs to complement shortfalls in the public education sector, and likewise, public needs to complement private. The private education sector must also acknowledge its shortcomings and strive to enhance children's qualities and capabilities leveraging on such complementary relationships between private and public.

Haruo Kimura

Haruo Kimura