Data-based Discussion on Education and Children in Japan

- 1. Bukatsudou--A Puzzling Activity that Most Students Join

- 2. Analyzing Juku--Another School After School

- 3. Low Self-Esteem Among Japanese Children--How to Overcome This Issue (This paper)

- 4. Issues Regarding Japanese Children's Reading--In Association with the Effects of Reading

- 5. Now's the time amid COVID-19 fear, let's close up on the positive side of a "well-regulated lifestyle"

- 6. To prevent the "cycle of poverty" -current situation in Japan concerning continuation of education to college

Low Self-Esteem Is an Educational Issue in Japan

Japanese children are often said to have low self-esteem. In fact, results of several international studies indicate that Japanese children do indeed tend to have low self-evaluation. This situation has been considered a major educational issue in Japan.

In this article, I aim to identify changes that have been occurring in education in Japan with a focus on self-esteem. The term "self-esteem" is generally considered synonymous with "pride" or "self-confidence." Also, in the field of psychology, there are studies on "self-respect," "self-efficacy," "self-competence" and "self-acceptance" among others. While the concepts of "self-esteem" and such terms are similar in ways, they are essentially different. In this article, however, I define "self-esteem" as "consciousness or emotion of perceiving oneself in a positive way" and do not strictly distinguish it from the terms above. Based on data, I would like to explore the following questions: Do Japanese children actually lack such positive consciousness or emotion? If so, what problems does this accompany? How is the education sector in Japan trying to overcome this issue? Moreover, have policies aiming to tackle this issue been successful?

70% of Japanese Students Feel like They Are a Failure

First, let us verify whether Japanese children actually have low self-esteem.

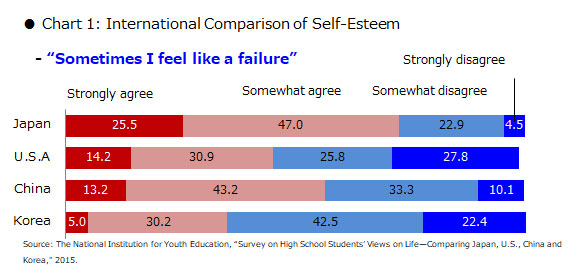

Chart 1 contains data that is often cited by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). This survey ("Survey on High School Students' Views on Life," The National Institution for Youth Education, 2015) asks upper secondary school students whether they agree/disagree to the statement "Sometimes I feel like a failure." While this question does seem rather direct, the chart shows that over 70% of the Japanese upper secondary school students agreed to this statement ("Strongly agree" or "Somewhat agree"). China came in second with 56.4%, followed by the United States and Korea with 45.1% and 35.2% respectively, revealing a difference among societies.

Other surveys also reveal similar tendencies among Japanese children, although results vary somewhat depending on the question itself, how it was asked, or who the target was. For example, in an international comparative study we conducted in 1994 targeting elementary school students in five cities ("Monograph/Elementary School Children Now" Vol.14-4," Japanese only), the rate of affirmative responses for categories on self-image including "I am kind," "I am a hard-worker," "I am good at sports" and "I have good school records" was lowest for children living in Tokyo. Also, in a study conducted in 2006 targeting elementary school students in six cities ("Basic Research on Academic Performance, International Survey of Six Cities"), children living in Tokyo had the lowest self-evaluation of their grades, suggesting that they are unconfident about their academic performance. Such survey results give the impression that Japanese children actually do have low self-esteem.

Also worth noting is the fact that not only children's self-evaluation, but also Japanese parents' evaluation of their children's growth tends to be low. Although slightly outdated, a study conducted in 1993 by the then Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture ("International Comparative Research on 'Home Education '") revealed that among parents with children of ages 10 to 12, those who "are satisfied with the growth of their children" accounted for over 80% in the United States, the United Kingdom and Sweden, but less than 40% in Japan. Japanese children's low self-evaluation is most likely affected by such negative evaluation from those close to them.

Problems Accompanying Low Self-Esteem

What kind of problems does low self-esteem produce?

Bandura, who is recognized for his study on self-efficacy, revealed that the more efficacious one's outlooks are on one's behaviours (the more confident one is), the more he or she will intensify his/her efforts (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy is the acknowledgement of the possibility of whether or not one has the capability to achieve a certain goal. If one believes that one can achieve a goal, he or she is more likely to take action, and conversely, if one thinks one will fail, he or she is less likely to take action. Self-efficacy involves not only confidence in oneself and value recognition, but also the difficulty and abstractness of a goal. It therefore may not be so simply put, but one can imagine that if one judges that he or she is not capable or may fail based on past experiences, he or she will not be motivated to take action.

I verified whether the same can be corroborated from data on Japan. Based on a joint panel survey by Institute of Social Science of the University of Tokyo, and Benesse Educational Research & Development Institute ("Parent-Child Study on Children's Lifestyle and Learning 2017," Japanese only), I regarded the category "I can state my strengths" as an indicator for self-esteem, and analyzed whether affirmative/negative responses were correlated with motivation or actions toward studying. I found that the "affirmative group" tended to respond that they "like studying," regardless of gender, grade or academic performance. For example, among upper secondary school students, the response rate for "like studying" was 43.0% among the "affirmative group," but 29.7% among the "negative group."

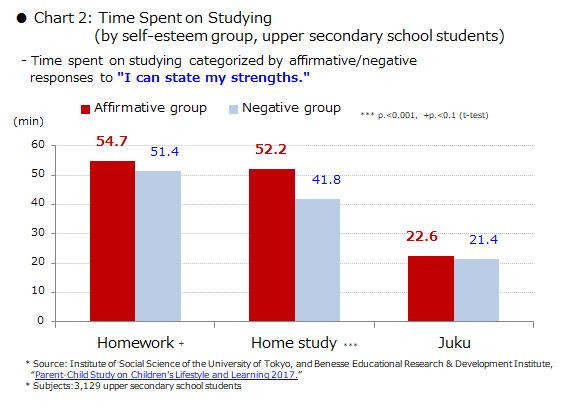

Similarly, I calculated the average time spent on studying by categorizing the samples into the "affirmative group" and "negative group." Again, the "affirmative group" tended to spend more time on studying regardless of their attributes. Chart 2 shows the data of upper secondary school students as an example. While the difference was small in time spent on semi-compulsory studies such as "homework" or "juku (private supplementary tutoring classes)," it was significant for voluntary studies such as "home study." This suggests that if students do not have a positive self-image, they will not be motivated to study, making it difficult for them to study voluntarily.

Impact on Education Policies

The above sections revealed that Japanese children have low self-esteem and that this has a negative impact on learning. While this situation was not acknowledged as a major educational issue in Japan prior to 1990, I feel that awareness spread rapidly during the 1990s. For example, in 1998, the Central Council for Education whose role is to consider the country's educational guidelines, issued a document titled "Discussion on Emotional Education from Childhood." This document repeatedly depicted how low children's self-esteem was and stated the following as a challenge:

- Given such circumstances as the low level of proactiveness and lack of self-esteem or self-usefulness among today's children, it is important to deploy education that evaluates children's strengths and cultivates their individuality according to their abilities/aptitudes or interests, and to enable children to feel a sense of fulfillment and achievement.

This awareness basically has not changed to date and is reflected in education policies. The "Courses of Study" issued in 2017 highlights that going forward, schools are expected to nurture individuals' self-esteem (MEXT, "Commentaries on the Courses of Study,"). In a rapidly changing society, such qualities and capabilities are deemed necessary for children to become creators of a sustainable society.

Changes Occurring in Education in Japan

How has this emphasis on self-esteem taken root in education in Japan? I would like to explore the impact on schools and classrooms using data.

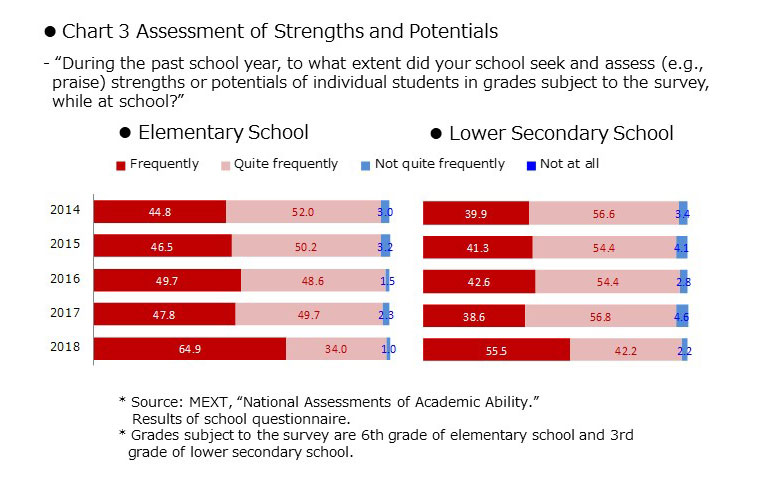

Chart 3 is based on an annual survey conducted by MEXT titled "National Assessments of Academic Ability," and shows the results to the following query in the school questionnaire: "During the past school year, to what extent did your school seek and assess (e.g., praise) strengths or potentials of individual students in grades subject to the survey, while at school?" I would first like to point out the significance of MEXT asking schools this question. This question was added in 2014, implying that MEXT places importance on efforts to "seek and assess strengths or potentials." Affirmative responses ("Frequently") increased significantly in 2018. 2018 marks the first year of a transition period to the new "Courses of Study," and schools are expected to introduce new educational contents and methods, including shifting to a teaching method called "active and interactive deep learning (i.e., active learning)." Schools are offering more activities that encourage children to think collaboratively and express themselves. I assume that through such activities, there is increased awareness toward assessing children's qualities and capabilities from various aspects instead of simply comparing their level of knowledge or skills (proficiency).

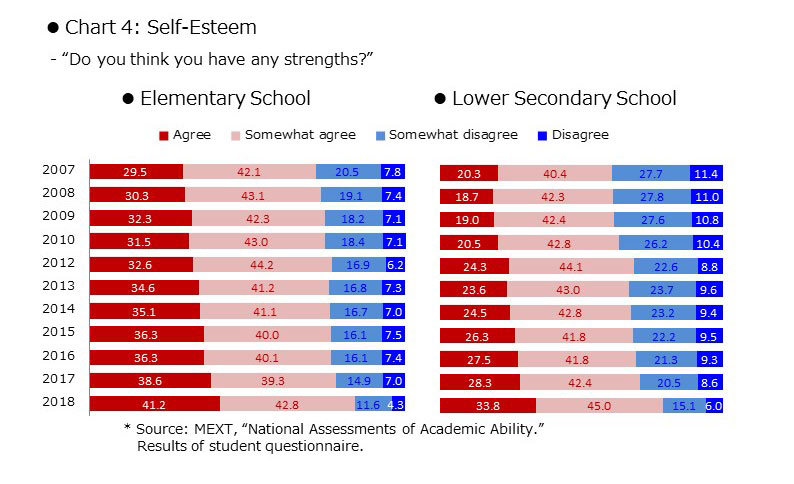

Such changes in teaching methods have also had an impact on the children. The survey also asks children whether they think they have any strengths. Results are shown in Chart 4. The number of those who responded "Agree" has been increasing yearly, indicating that the level of children's self-esteem is improving. Additionally, this upward trend has been a steady one, rather than short-term, and the significant improvement in 2018 is consistent with results of the school questionnaire.

Metacognition and Self-Esteem

Children's low self-esteem has been raised as an issue in Japan to date. Yet, as corroborated by data, the situation has been improving. Such improvements are not unrelated to the movement to evaluate diverse children's qualities and capabilities. I believe that in future education, it is ideal to apprehend and accept each child's strength both at school and at home.

Meanwhile, one might question whether low self-esteem is actually an issue. Japanese have a culture of regarding "humbleness" as a virtue in interpersonal relationships. It may be possible that Japanese do not necessarily have low self-esteem, but express self-esteem in a different way or to a different extent depending on the situation. Also, although having excessively low self-esteem may be a problem, having excessively high self-esteem most likely has its side effects too. There is a study indicating that children learn strategies to hide their incompetence in order to maintain high self-esteem (Covington, 1992). According to this study, when faced with a difficult challenge, a mental mechanism is activated, where children intentionally do not try hard in an attempt to avoid attributing the cause of failure to their capabilities.

If this is true, children should ideally have appropriate self-esteem. They should recognise their characteristics (what they are good at/not good at, or what they like/dislike), be able to determine where they stand relative to their goals, and contemplate strategies to bridge the distance to their goals. Furthermore, they should focus on the process of achieving their goals rather than reacting simplistically to successes and failures by attributing the cause to their "capabilities." I believe such functions are equivalent to metacognition. Exercising metacognition may be difficult depending on the child's development stage and perhaps it is better for younger children to feel omnipotent. However, as they grow older, it would be best to foster self-esteem accompanied by metacognition.

References

- Bandura, A., 1997, Self-efficacy: the exercise of control.

- Covington, M.V., 1992, Making the grade: A self-worth perspective on motivation and school reform.

- Kage, Masaharu, 2013, Gakushū Iyoku no Riron--Dōkizuke no Kyōikushinrigaku (Learning Motivation Theory--Educational Psychology of Motivation), Kanekoshobo.

- Sato, Yoshiko, 2009, Nihon no Kodomo to Jisonshin--Jikoshuchō wo Dō Hagukumuka (Japanese Children and Self-Esteem--How to Nurture Self-Assertion), Chukoshinsho.

Haruo Kimura

Haruo Kimura