1. Conducting a Class for Third Year Elementary Students to Learn Coaching

Takatoshi Akiyama says that when he listened to his students' conversations in discussion time in class and during breaks, in many cases he noticed that there was no give-and-take: students were simply saying what they wanted to say, without acknowledging what the other party was saying.

If you can listen carefully to what the other person says, it makes you interested in them and keen to hear what they have to say. If the other person senses your enthusiasm, they will be more motivated to talk, and the peer-to-peer exchange of ideas will be enhanced. With this in mind, Mr. Akiyama conducted a class for his third-year elementary school group in which the students learned about coaching, a method which Mr. Akiyama had previously learned himself.

Coaching:

A process of supporting the actions required to achieve certain objectives, by enabling coachees to gain new insights and additional perspectives through ongoing interactive communication. Widely used in corporate settings as a management technique to unlock the potential of individuals and organizations.

Mr. Akiyama explained his motivations as follows:

"Many books have been published about coaching for schools, and coaching is increasingly used as a skill for teachers when engaging with students. But I thought it could be more than that: by giving students themselves the experience of coaching, maybe dialogue amongst students can be enhanced even if their teachers aren't directly involved."

Mr. Akiyama's aim was for all members of the class to gain the ability to listen to other people's ideas in class and in everyday life, and to reflect on their own thinking.

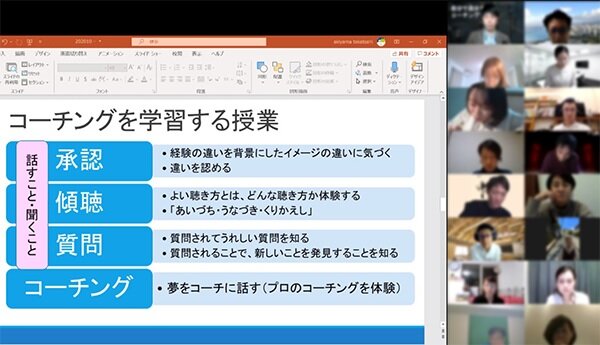

In the Learning Space Lab demonstration class, Mr. Akiyama conducted a class on "acknowledgment," which was the first in a series of four classes that he had held for third year elementary students in Japanese. The demonstration class attracted around 20 participants interested in coaching, including parents and other working adults as well as schoolteachers. Some even participated from outside Japan.

■Outline of the Learning Space Lab Demonstration Class

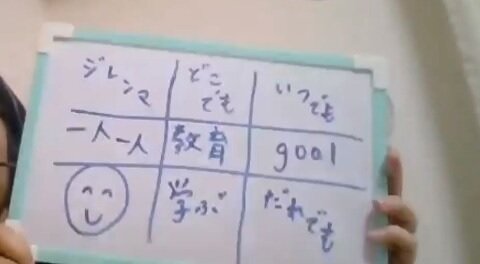

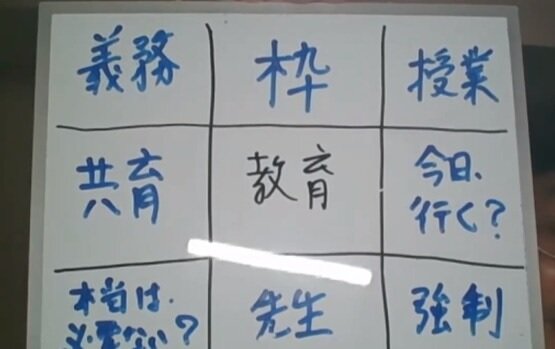

- Provide paper and writing implements. Participants rule two horizontal and two vertical lines on the paper to create a grid of 9 squares.

- In the central square, they write the word "apple."

- In the remaining eight squares, they write words associated with "apple." The time limit is 2 minutes.

Nouns, adjectives, and all other types of words are acceptable. Each word must stem directly from "apple," so that it does not become a word chain game. - Participants divide into groups of four or five, introduce themselves to the other members of the group, then present their words. Once everyone has presented, participants explain to one another their reasons for writing the words.

- Participants each draw up another 9-square grid, write the word "education" in the center square, and other words they associate with "education" in the remaining squares.

- Participants re-form the same groups that were used in step (4), and again present the words they have written. This time, listeners select one of the eight words presented and ask, "why did you choose that word?." The presenter responds. This is done in rotation, with the first presenter asking the fourth, the second asking the third, and so on.

In the class Mr. Akiyama held for third-year elementary school students, the same word, "apple," was used in the first round, but in the second round it was "cattle." This was changed to "education" in the demonstration class, as most participants were educators.

2. Activities that Naturally Motivate Students to "Listen"

Participants clearly enjoyed the group work where they shared with one another the words they had written, empathizing when another participant nominated a word that they had also used, and expressing surprise at words that did not match their impressions.

Comments in the Chat afterwards included "it was fun to discover what other people are thinking," and "I got the feeling that the words encapsulated the worldviews of the people who thought of them."

After the demonstration class, participants posed a variety of questions to Mr. Akiyama, which formed the basis of a discussion session chaired by Mr. Shogo Minote, a teacher at Koganei Municipal Maehara Elementary School, Tokyo.

Mr. Minote picked up on the strategies used to kindle participants' desire to listen to others. By having all participants contemplate the same word, the activity fostered a shared interest, which is the foundation for interaction. The group work created a natural motivation to communicate, with participants wanting to hear what others had to say and to share their own ideas.

Mr. Minote suggested that this kind of interest in others is the most crucial precondition for interaction.

"In Japanese classes, when the focus is on 'speaking and listening,' I think it's common to deal firstly with models such as 'listening quietly,' 'speaking clearly,' and 'taking turns.' Interaction, however, cannot be achieved simply by following models. The appropriate attitude to adopt when listening and the way of making yourself understood are things you acquire through the experience of conversation with others. Coaching involves developing an interest in others and listening to them, so I think it helps foster an interactive mindset."

Mr. Akiyama explained that he designed the activity firstly to help students appreciate the enjoyment of "listening."

"If you learn set question patterns, for example, then you would be able to ask the other person questions. However, if you aren't interested in him or her, you would just stick to the patterns, and it's disrespectful to ask about things that you don't really want to know. If you can develop a natural interest in what the other person is saying, it becomes more enjoyable to listen, and you become motivated to listen even more."

One strategy here is word selection, which was part of the task in Mr. Akiyama's class.

"If you select something that's familiar but can be interpreted in many different ways, participants engage actively in the group work. I chose 'cattle' because it is a word that can refer to different contexts, such as living creatures, and food, so I thought that there would be differences in the way the participants approached it, even among third-year elementary school students."

3. Firstly Make Students Aware of "Differences"

The next issue was whether or not elementary school students were capable of learning coaching. Mr. Akiyama reported that when he introduced this class at a different school, the response was: "children at a private elementary school in the Tokyo area could probably do it, couldn't they?"

Mr. Minote explained that because skill acquisition is not the aim of this lesson, it could be conducted even in the lower levels of elementary school, provided it was adapted to the cohort.

"The primary aim of a lesson on coaching is to have students experience the enjoyment of being listened to, and cultivate an interest in listening to what others have to say. The task is to come up with single words, so students of any level should be able to write their ideas down. As long as the teacher provides solid support to enable students to interact effectively, I think this class could be conducted at any level of schooling and scholastic ability."

Meanwhile, in relation to stages of development, one participant expressed doubts, observing that while adults are able to enjoy differences, in some cases third-year elementary school students may be unable to accept such differences so readily. Mr. Akiyama responded by suggesting that as well as supporting such students, teachers need to design the activity so that the interactions do not go too deep.

"Coaching is originally designed to develop deeper thinking through interaction, but for children who are unable to accept differences, a simple engagement with others can feel like a cross-examination. So in this class I deliberately stop at the level of sharing the eight words. It's enough that students understand that different people may associate different things with the same word."

Before beginning the activity, Mr. Akiyama told the class that the rule was not to criticize or reject anything that another student says. He took care to ensure that all students were able to come up with their own words, express them freely, and not feel ashamed of their ideas, even if they couldn't fill all eight squares of the grid.

4. Interactive Capabilities Required of Teachers and Students

In Mr. Akiyama's actual class, the second period on "active listening" provided an opportunity for students to share the awareness they had gained, and through this process, develop further awareness. Two scenarios were conducted: one where the students playing the roles of listeners nodded as they listened, and the other where they did not nod or make any other active response. Mr. Akiyama reported that most students appeared anxious in the no-response scenario.

Through their own experience the students realized how unpleasant it is not to be listened to, and gained an understanding of the importance of listening attentively to others."

Moreover, Mr. Akiyama intentionally used specialized terms such as "coaching" and "acknowledgment," explaining the terms' meanings so they could be understood by third-year elementary school students. He explained that precisely because these terms were specialized and appeared difficult for children to understand, they gave his students a sense of excitement at encountering something new, and raised their motivation to learn.

"Children seem to take a more positive approach to their learning in an atmosphere where they can enjoy a sense of extending themselves by using the same vocabulary as adults. When discussing a topic in their class meetings, my students actually made use of what they'd learned, saying things like 'let's listen actively to that' and 'we need acknowledge this'."

Having listened to Mr. Akiyama's account of his own students, one participant made the following comment:

"No matter how many times you say 'let's listen carefully' in class, students won't listen. I realized the importance of nurturing a desire to listen in the first place. I'm convinced that when the aim is cultivation of this kind of motivation, it's worth running a coaching class regardless of the year level."

These insights can be placed in the context of the new national curriculum guidelines, which envisages that teachers in the future will play the roles of coaches and facilitators more than conventional teaching. Mr. Minote had the following to say on this topic:

"The ability to interact with others can also enhance your capacity to question yourself. Confronting your inner self and digging deeper into it by asking questions such as why you feel like doing a certain thing, is surely part of the process of autonomous growth.

Mr. Akiyama added:

"I believe that as more and more activities require students to think and act for themselves, teachers will be expected to provide support for students to move forward in their preferred directions, and this will require the skills and mindsets of coaching. The same goes for students themselves: as part of their approach to learning they will need interactive mindsets and skills such as listening, speaking, and asking questions. I plan to continue fostering such attributes in my teaching."

Takatoshi Akiyama

Takatoshi Akiyama Shogo Minote

Shogo Minote