1. Starting Point: Why do Students Get So Engrossed in Games?

Kan Tanaka, a Social Studies teacher at a municipal junior high school in Tokyo, has interests in exploratory learning and PBL and is working to create classes where students take the initiative in their learning. One approach he focuses on in particular is "gaming."

Curious as to why students become so engrossed in games, Mr. Tanaka started to explore what makes games so attractive, in order to obtain some hints on how to get his students just as engrossed in their studies. This led him to the idea of "gamification." Reading publications on this topic, he became aware of the idea that elements of games could be applied to areas other than gaming.

"In a game the goal is clear, and you pursue a PDCA cycle in order to attain it. I thought that if I could incorporate some elements of gaming into my classes in a positive sense, maybe students would be more motivated to learn for themselves."

In his third-year Social Studies class, Mr. Tanaka operated a "money making game." He cut out small pieces of paper to use as money for purchasing shares and doing other things to boost capital. Students were divided into groups of 4-5 students to establish companies, with a total of nine companies competing in a single class. The company having the most funds at the end of the game was declared the winner.

"I ran this game when we were studying the introductory unit on economics. My aim was to immerse students in the actual experience of earning money, so they would engage with more interest in their learning about economic activities in society."

2. Participants Become Engrossed as They Strive for Victory

Participants in the demonstration class for Learning Space Lab were given the same experience as in Mr. Tanaka's actual class. Mr. Tanaka provided the same level of explanation as he gave his actual students, then the game began. Some of the rules were modified for the demonstration class, as it was held online.

Outline of the online version of the "money making game":

Procedure:

- Participants form companies in groups of four and assign roles within the group: president, secretary, accountant, and ordinary employee.

- The company presidents are each given 1 million yen for start-up capital, and purchase one card from a pack of "job cards" A-H.

- Each company produces information that satisfies the conditions shown on their card, and sells it for 100,000 yen each to generate revenue.

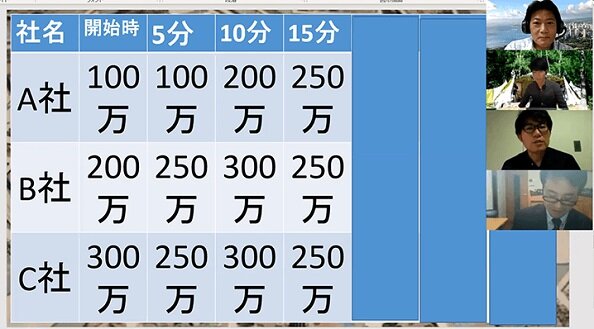

- Using the revenue they have gained, companies can purchase shares in the other three companies. Share prices and dividends vary from company to company, with prices fluctuating every five minutes.

- The time limit for the game is 30 minutes, and the company with the most funds at the end of this time is the winner.

- No loans are permitted.

- Only one person from each company can come to see the teacher (who is in the main meeting room in the case of a Zoom class) for the purpose of buying "job cards."

The class used Breakout Rooms in Zoom. Each company holds internal discussions in its own Breakout Room, and comes to the main room to sell information and trade shares.

*Participants were provided with a guidance sheet explaining the game, to be used as reference.

Participants were divided into groups of four, forming five companies in total. After the explanation, each company was assigned its own Breakout Room, and they began by assigning roles within the company. While the company president was purchasing a "job card" in the main room, the other members introduced themselves and confirmed how the game was run. The game began when the president returned from the main room with a "job card" and conveyed the conditions for producing the information that would become the company's product.

The conditions written on "job cards" included names of stations/airports, potential places to go on a date, and the names of songs and singers.

Some participants were confused because they could not grasp the rules properly, or were using Zoom for the first time, but those who were more familiar took the lead. Mr. Tanaka had expected this to be the case, and based on his experience running the game successfully for junior high school students with the same level of explanation, he encouraged the participants by saying, "just give it a go—you won't know until you try." This prompted the companies to swing into action.

When producing and collating information to meet the conditions stated on their "job cards," rather than simply writing down their first thoughts, each company devised its own approach, such as having participants search for information online and use the Chat function to send ideas to their president. They also took care to avoid duplication, for example by selecting local station names for the "stations and airports" category.

Each company kept a close eye on the other companies' movements, with participants discussing questions such as how much information would be needed to ensure victory, and how the other companies might be gathering their information.

When buying and selling shares, they also thought carefully about how to increase their funds, proposing strategies such as purchasing shares to obtain dividends rather than focusing on producing information, and considering the timing of their purchases to maximize profit.

Very soon the 30-minute time limit was up, and victory went to the company that had sold names of stations and airports, which had earned over 40 million yen.

3. Fiction Serves as the Key to Unlocking Creativity

After the demonstration class, there was time for reflection centered on a question-and-answer session between Mr. Tanaka and the participants, chaired by Mr. Shogo Minote, who is conducting student-centered class improvements at the Koganei Municipal Maehara Elementary School, Tokyo.

Firstly, Mr. Minote asked participants for their impressions of the "money making game." Many commented that had been very focused on what they were doing, suggesting that they became absorbed in the game environment naturally. Mr. Minote revealed that some companies in the game had used other online tools to share information, and others had generated their information using internet searches. Participants seemed impressed at the way teams had come up with their own strategies for winning within the rules of the game.

There followed a number of questions regarding how students had responded in Mr. Tanaka's actual class at school. Mr. Tanaka explained the differences between the game he had run at school and the one in this demonstration class, then outlined the students' response as follows:

"Students did everything they could to make money, devising strategies not written in the rules of the game, such as lending and borrowing tools and people, and trading information. Up to seven different companies merged into one, despite the students never learning about mergers in class. I was astonished at how creative they were."Mr. Minote commented:

"I believe that participants were able to experience how creativity can be unleashed as you become engrossed in an activity. Because the game is a fictitious environment, you can allow yourself to be deceived, and it's easier to give free rein to your ingenuity and creative abilities. I feel that this is the true power of gamification."

4. Balancing the Fun of Games with Curricular Teaching

The next question concerned the stage of learning at which the game should be conducted. Mr. Tanaka envisaged using the game at the introductory stage of a curricular unit, and thus conducted it with an emphasis on immersing students in economic activity. The suggestion was made, however, that in the context of a Social Studies class for third-year junior high school students, the game could be used after introducing the three key functions of currency. Mr. Minote commented:

Using the game at the introductory stage is one example. As they engage in the game, students build a shared culture. Then as the course progresses, they can recall scenes from the game and share reflections that give greater depth to their learning. But I don't think there's any single correct way to divide between game elements and curricular content. I believe that the balance between learning stage, purpose, and content to be mastered can be patterned differently depending on the goal.

Mr. Tanaka recalled that in practice, some students referred back to their experiences in the game in later classes—not only in the economics unit, but also when discussing economic activity in relation to the SDGs.

Participants were also highly interested in online teaching. Envisaging that face-to-face teaching may be suspended again in the future, they shared their thoughts regarding how to conduct the class online. Comments included:

"It's possible that some students who would have participated if the class was held face-to-face will be reluctant to participate online. It's essential to find ways to make them want to participate.

One advantage is that students can use the Chat function to state their opinions, without having to verbalize them aloud. Students unwilling to speak up will find it easier to participate in online classes."

"If you use the Broadcast function effectively to disseminate information, it might also be possible to make students aware of the role of the media."

"It's a lot of work for a single teacher to run the game on their own, so maybe students could be appointed as assistants."

Discussion continued unabated, as participants acquired insights for use in improving their own teaching practice.

Finally, Mr. Tanaka offered some words of reflection.

"Responses to the student questionnaire I conducted after the class revealed a wide variety of opinions, ranging from enthusiastic endorsements such as 'I learned the true essence of economics!' to those such as, 'it seems to be nothing more than a game.' Hearing the responses of participants today made me realize the potential of gamification and online teaching. I'd like to develop this work further, with a view to the balance between learning and playing."

Kan Tanaka

Kan Tanaka Shogo Minote

Shogo Minote