There are a few things in life I am truly passionate about. All aspects of the development of young children, teaching English to non-English speakers and researching ways to ensure quality education are all at the top of my list. During my 20 years of classroom experience as an English Second Language (ESL) specialist, I have worked in Africa, Europe, Australia, and Asia. My first classroom experience as an English teacher at an exclusive private high school in Africa highlighted my desire to work with young learners, I wanted to be the one to introduce children to English to establish a love and long-term success. In Europe, a lack of focus on English surprised me while in Asia, I was struck by the restrictive curricula which often didn't meet the needs of young learners. Children wanted to sing and dance, be creative and engage in the practical learning of English. I wanted to build an environment where I could steer learning through the activities children enjoyed most, while building on sound ESL principles in a balanced approach. In Australia I started an ESL playgroup for foreign families where we enjoyed more freedom, the group grew to 200 families within two years.

Relocated back to Asia I had grown in confidence in my international classroom experience, and I was ready to become an academic leader. I earned my M.Ed. in Early Childhood Education (ECE) specializing in preschool Japanese children with honors and received membership with Kappa Delta Pi (the International Honors Society in Education). Professionally I designed and implemented a specialized ESL baby program as part of a large business development strategy for a well-respected Japanese tutoring company. The more I studied different ECE curricula and pedagogies throughout the world, the more I wanted to know! I embarked on my Ed.S. in Education Leadership degree with a focus on International Education while enjoying employment as an English consultant/ teacher at a niche Japanese preschool in Singapore. At our little school, we were achieving phenomenal success in English through our unique method. It was inspirational! I enjoyed conducting many action research projects at school, publishing short articles in Japanese magazines of Singapore, consulting with parents, offering short teacher training sessions, and being involved in every aspect of the school and the Japanese community. I earned my Ed.D. in Education Leadership with honors by once again focusing on the Japanese community of Singapore. Being an English consultant to our Japanese community, strategizing with education start-up companies, researching, advising parents on English learning and international school-related topics became my passion and my life. COVID-19 struck and our family was relocated away from Asia, to Dubai in the Middle East.

This is where I have had to embark on the road to discovering my new place as an ESL consultant and strategist in early childhood education. After eleven years of serving private Japanese early childhood education environments, nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to experience. I was met by an early childhood education industry dominated by various interpretations of the British curriculum and a very strong singular focus, free play in preschools. I visited an array of schools in the hope that I would find my happy place, where I could once again serve, build relationships, and advise a community. With all my academic knowledge and experience, I was unable to reconcile what I was seeing with what I believed in. I began a methodical process of objective comparison as I had done during my studies so many times. In my head, I ran through a list of vital skills the Japanese system taught our young children: independence, collaboration, responsibility, cohesion, perseverance, self-reflection, effective communication, and self-control. Similar to the British system, Japanese preschools also promoted play-based instruction, concentrating on child-directed activities, yet our approaches differed vastly. One of the largest differences was the intentional development of executive function in Japanese early childhood education.

What is executive function

Executive function describes the self-regulation skills or the mental processes enabling students to focus attention during activities (Roskam et al., 2014). Fundamental skills included in the concept are planning, self-control, working memory, flexibility in thinking, self-monitoring, time management, and organization skills (Moriguchi, 2014). With young children spending a significant and increasing amount of time in school environments, the development of executive function (EF) skills is increasingly emerging as the responsibility of teachers. Studies have found EFs as reliable predictors of long-term success in academic, professional, and personal lives, while early year challenges of EF not only negatively impacted long-term learning and success, but an increased deficit over time (Moffitt et al., 2012; Moriguchi, 2014). Recent studies have repeatedly highlighted the importance of self-restraint and other executive function skills in preschool-aged children as reliable predictors of success in academics and higher socioeconomic standing in adulthood (Ten Braak et al., 2019; Harwood-Gross et al., 2021; Tiberio et al., 2017).

Components of executive function

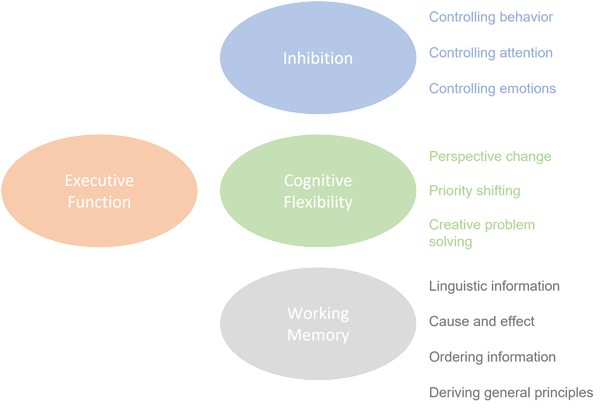

Executive function skills start developing shortly after birth. Studies found the optimum time for the natural development and training of EF skills during the early years with the most dramatic growth occurring between the ages of 3 and 5 (Diamond, 2012). This necessitates the inclusion of thoughtful and robust strategies for the development of EF skills as essential in preschool environments. EFs encompass a group of control functions to assist us in regulating reactive behavior, managing impulses, and allowing the brain to consider, think, and focus rather than spontaneously respond. Three main categories are generally accepted in studies: inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory (see Figure 1). With the development of cognitive functioning throughout preschools and into further learning, these form the foundations for eventual reasoning, planning, and advanced problem solving (Diamond, 2012; Moriguchi, 2014).

Inhibition pertains to (1) the ability to control behavior including the ability to control impulsive responses or the resistance of temptation, (2) the ability to focus and concentrate attention on a specific task, and (3) the ability to control emotions and respond appropriately within the social context. Strong development of inhibition is often associated with an individual's ability to delay gratification or control response in challenging situations. A longitudinal study conducted by Moffitt et al. (2012) suggested children aged between 3 and 11 who struggled with poor inhibition including a lack of perseverance, lack of attention, and impulsivity earned less, had worse health, were more unhappy, and had higher criminal activity 30 years later than children with strong development of inhibition (Diamond, 2012).

Working memory describes a human's ability to retain and process information to create meaning and derive valuable information from experiences. It is needed to derive value from linguistic information. Working memory allows for the ability to create, recreate, and organize lists, draw conclusions from cause-and-effect situations, and develop general hypotheses of general principles from information to predict future events (Diamond, 2012; Roskam et al., 2014).

Cognitive flexibility as the words suggest pertains to the ability to adjust and modify thoughts, opinions, rational strategies, or solutions according to shifts in information or priorities. It includes the ability to recognize and understand the perspectives and points of view of others, the ability to approach solution finding from different angles, to start, stop, and switch between varied cognitive activities as needed, and to shift priorities between wide-ranging activities (Diamond, 2012).

The development of executive function in children

Results reported by Roskam et al. (2014) revealed effective scaffolding of learning to be the most reliable predictor of EF development in young children. Maternal scaffolding in studies where children spent the majority of time at home coupled with imitative learning was highlighted as particularly important. The importance of social interaction, specifically interaction with parents and significant adults for the development of EFs in the early years are well documented (Moriguchi, 2014; Tiberio et al., 2017). Interaction with peers, especially for collaborative learning purposes where conflict and separate opinions emerge could lead to adverse situations presenting opportunities for the development of executive control. Situations challenging children's current self-control, problem-solving, and reasoning abilities and tasks requiring collaboration or delayed gratification were all ways to enhance EF.

Ten Braak et al. (2018) highlighted the challenges unstructured, play-based early education posed to the development of EF skills. Limited time for intentional, structured teacher-led activity created an environment where it was anticipated that children would learn and develop at their pace through free play. Considering the relationship between mathematics development, and the vital role of expressive vocabulary for self-expression and regulation, a more comprehensive methodology with focused activities to improve and support the development was proposed (Tiberio et al., 2017).

Research suggests the successful development of EF skills from intervention depends on the approach to the activity (Harwood-Gross et al., 2021). Groups of troubled adolescents were assigned to two different Taekwondo activities. In the traditional martial arts group, various aspects of discipline and self-control were incorporated and emphasized in conjunction with the physical aspects of Taekwondo. The second group received instruction and training solely on the physical aspects of the sport for competitive purposes. Students of the traditional training group presented less aggression, improved self-control, decreased anxiety, improved social interaction, and self-esteem. It was proposed that the intentional instruction on, and practice of self-control and disciplined behavior had a greater interventional impact on the development of EF skills (Diamond, 2012; Harwood-Gross et al., 2021).

My experience with the Japanese preschool approach

Revisiting knowledge gained from research (Diamond, 2012; Moriguchi, 2014; Moffitt et al., 2012) on the importance of the various categories and skills contained within executive function confirmed the uneasy feeling I felt at the idea of children engaged in unstructured play for unlimited time every day. The evidence on the benefits of play is clear, this is not the issue at hand. Allowing children to only do the activities they enjoy, with no interruption to the cognitive function, no obligation to adhere to some form of a schedule, and no scaffolding from adults to nurture and develop from current levels of EF skills do not bode well for our young learners. The Japanese environments (Yochien) where I have worked have been play-based, yet there have been lofty expectations of children, and a fairly rigorous structure was followed. As I was investigating and thinking of the differences in approaches, I tried to pinpoint specific examples and activities throughout the day of how Japanese environments successfully created opportunities for EF development. Started from the organization in preschool bags which include (below) children are expected to unpack and reallocate to the specified areas assisting in organization and planning development:

- tsuuen renraku bukuro (Kindergarten "contact" bag)

- uwabaki bukuro (bag for school shoes)

- obentou bukuro (bento bag - bag for boxed lunch)

- hamigaki settoire (bag for toothbrush set)

- taisougi bukuro (gym bag)

- hasami bukuro (bag for scissors)

Despite promoting a hands-off approach, teachers observed keenly and utilized teachable moments to talk to children and discuss challenging situations, reactions, and feelings during those instances, including problem-solving for improved behavior in the future (Hayashi & Tobin, 2014). Children were expected to participate in clearing away toys, cleaning, and dishing up activities for themselves and classmates teaching a variety of EF skills. A schedule with varied activities was followed whereby children were compelled to stop one activity and start another, ideal for developing cognitive flexibility. Large group activities often involved the introduction of tasks and challenges for children to solve without adult interference. Even though these were often presented in the form of a play-based activity or game, the goal was the intentional development of effective communication, negotiation, creative problem solving, understanding of different perspectives, the organization of information, and focused attention on a specific task.

There were countless examples of activities throughout the day where Japanese children practice controlled focus. From taking their outdoor shoes off and putting their indoor shoes on for students as young as two years old, to packing bags away, cleaning up toys, completing art projects, learning the correct words to songs, reciting Japanese poems, or sitting quietly during story-time. Focused activities, often short and interspersed during the school day developed (even in the youngest learners) children's ability to listen, focus, perseverance, the importance of completing a task, participation, and possibly crucial to Japanese culture, being part of the larger group and collaborating with others for greater harmony all enhance children's EF skills. Whether teachers were aware of the inclusion of so many components to develop the categories within their classrooms, is not clear. Conceivably because Japanese culture expects strong executive functional capabilities from productive members of society teachers were driven to fully prepare children, focusing on these skills without fully realizing the benefits. The multiple focused activities throughout each day in the Japanese Yochien where I have been lucky enough to serve have created an optimal environment for the development of EF skills in young children.

Conclusion

Education leaders are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of executive function skills for transition into elementary school, long-term academic success, happiness, socioeconomic attainment, and greater career prospects. Considering the importance of intentional development during the optimal ages of birth to five, early childhood educators have a key role to play. Approaches towards the development of inhibition should include opportunities for children to practice controlling their emotions, focus, and behavior. EFs also necessitate the introduction of adverse conditions for children where they are expected to participate in personally less favored activities and events which require uncomfortable switches between cognitive activities.

Current strategies to improve executive function in students who struggle with issues of inhibition, self-restraint, impulse control, and social issues include structured, disciplined, focused activities where character development and self-control are accomplished. Intervention programs with measurable success have included computer-based memory/reasoning training, interactive board games, task-switching computer training, martial arts classes, structured school readiness programs, and academic additions to school curricula (Diamond, 2012; Harwood-Gross, 2021). Despite the overwhelming emphasis on play as the most important activity in many preschools today, it is not commonly used as an intervention method to enhance EF development. Play-based schools focused on unstructured activities may need to reconsider the introduction of focused activities with intentional development of EF skills through scaffolding. Japanese preschools offer an array of focused daily activities and teachers utilize teachable moments throughout the day to discuss and intentionally develop the distinct categories of executive functioning skills.

References

- Diamond, A. (2012). Activities and Programs That Improve Children's Executive Functions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 335-341.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412453722 - Harwood-Gross, A., Lambez, B., Feldman, R., Zagoory-Sharon, O., & Rassovsky, Y. (2021). The Effect of Martial Arts Training on Cognitive and Psychological Functions in At-risk Youths. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 707-714.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.707047. - Hayashi, A., & Tobin, J. (2014). Implications of studies of early childhood education in Japan for understanding children's social emotional development. Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 8(2), 115-127.

- Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., & Harrington, H. (2012). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108, 2693-2698.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108 - Moriguchi, Y. (2014). The early development of executive function and its relation to social interaction: A brief review. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 388.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00388 - Roskam, I., Stievenart, M., Meunier, J.-C., & Noël, M.-P. (2014). The development of children's inhibition: Does parenting matter? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 122, 166- 182.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2014.01.003 - Ten Braak, D., Storksen, I., Idsoe, T., & McClelland, M. (2019). Bidirectionality in self-regulation and academic skills in play-based early childhood education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 65, 1-11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101064 - Tiberio, S. S., Capaldi, D. M., Kerr, D.C.R., Betrand, M., Pears, K.C., & Owen, L. (2017). Parenting and the Development of Effortful Control from Early Childhood to Early Adolescence: A Transactional Developmental Model. Developmental Psychopathology, 28(3), 837-853.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000341

Annemarie de Villiers

Annemarie de Villiers