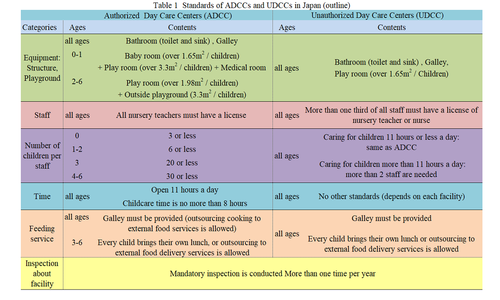

From a historical perspective, the origin of ECEC is in the philosophies of Pestalozzi, J. H. and Owen, R. It was originally considered to be advocating ECEC for children on behalf of poor working parents. On the other hand, these philosophies were based on the social situations of the 18th century, somewhat different from the present. There are numerous problems in Japan; expanding income gaps and an unmatching ECEC system with diverse labor forms. As a result, some children cannot receive the ECEC they need. It is pointed out that there are over 10 thousand children who are on the waiting list to enter ADCC. This is a serious problem, which leads to restraint of women's working, child poverty, and declining birth rates (Ikemoto & Tateoka, 2017). The OECD also pointed out the following; "Parents finding a good work/life balance is thus a critical issue for child well-being, as both poverty and a lack of personal attention can impair child development. A good work/family balance also reduces parental stress, and thus benefits both parent-child and parent-parent relationships (OECD, 2007)." There are Unauthorized DayCare Centers (UDCC) which act as receivers of those "waiting list children" in Japan. ECEC in Japan has several types of facilities; Kindergartens, Day Care centers (Authorized Day Care Centers: ADCC), Center for early childhood education and care, Municipal-level childcare service and Unauthorized DayCare Centers (UDCC) (Cabinet Office, Japan, 2016). Although UDCC are facilities which aim at child care services based on the Child Welfare Act, they do not meet the criteria of ADCC (Table 1). The classification UDCC includes Baby hotels, childcare services at unlicensed nurseries (including those originally certified by local governments, general unlicensed childcare institutions, baby-sitters, unlicensed childcare facilities within workplace), temporary childcare services, childcare services for sick children, family support center services, and others. Baby hotels are facilities which (1) run after 8 pm, or (2) nighttime care, or (3) more than half of children are temporal use. UDCC have received children who cannot enter ADCC, namely the problem of "waiting-list children". Baby hotels were operated mainly in urban areas in the 1970s to meet the demands of women who worked at night and on holidays. Initially, these baby hotels did not have adequate legal restrictions, which resulted in a series of infant fatality accidents in the 1980s. For that reason, supervision of UDCC including baby hotels was reinforced by local government. Despite that, accident rates are still high in those facilities.

Although UDCC have been recognized as facilities which take on children who cannot enter ADCC for several reasons, the authors clarified they have been utilized in areas where there were no waiting-list children (Onishi & Ohnishi; 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018). In this study the focus was on UDCC, in particular baby hotels, and it was clarified that UDCC in Japan have educational functions and a welfare role to support high risk families such as single parent, foreigner, disadvantaged parents. UDCC provide a safety net to those families against abuse risk. Moreover, UDCC staff provide a flexible response to parents' childcare needs that cannot be fulfilled by ADCC, and provide employment support (childcare support for irregular work such as irregular employment, nighttime and holiday work, freelance). They were trying to encourage children to interact, play, and have fun with other children by spending time in the facility, rather than be left at home while their parent(s) was (were) working. Taking advantage of the seemingly unstable conditions in which children do not always come every day, they provide them with an educational environment that allows individual children to pursue their own thoughts at those times. In addition, UDCC staff wanted to continue to support children and their parent(s), even though they couldn't secure their own wages. Through repeated interviews with them, it seemed that their thoughts and strong sense of responsibility led to the ideas of the educators mentioned above, which is the origin of ECEC. Moreover, it was also related to the idea of a symbiotic society that underlies inclusive education, which is often talked about in the context of education for children with disabilities.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the ECEC philosophies of the staff working at UDCC which is often regarded as problematic. In this way, we would like to think about what childcare should be, in particular to be a guide when considering ECEC in an inclusive society.

Method

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 5 staff members (2 directors, 3 nursery teachers) of UDCC (4 Baby hotels and 1 other UDCC) located in local cities. The childcare facilities targeted in this study were not stable or well-funded. The interview contents were (1) characteristics of users (their usage time, occupation, family structure, and nationality), (2) motivation of childcare, and (3) difficulty of UDCC (Onishi & Ohnishi, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018). In this study, we tried to analyze those narrative data from the standpoint of their ECEC philosophies comparing it with that of practitioners who generated the basis of ECEC (c.f. Pestalozzi, J.H., Owen, R., and Kurahashi, S.). The purpose and procedure of the study was explained to the participants and informed consent was obtained.

Results and Discussions

It became clearer that the staff involved in this study have a basic philosophy of supporting anyone who has ECEC needs. In particular, they emphasize supporting anyone who is vulnerable with ECEC needs. The following narratives were obtained; "We want to help families in difficult situations here and right now", "if parents didn't use our facility, their children would be left at home and it would lead to neglect (B director)", "If we abandon them, they will get lost on the road and will not be able to live."

Users of those childcare facilities are really in a vulnerable position at their work places. For example, those who work at nightclubs may often have their working hours and wages cut if their establishment attracts few customers, even if they are in working hours. Similarly, there are cases where parents who are part-time or non-regular employees are obliged to work shorter hours even if they want to work more. Teleworkers, who work only when they are requested to by their employer, such as freelancers, are considered to have a low need for childcare because their work style is to be a home employee. Some parents are in a socially vulnerable position, too. Single-parents and parents of foreign nationality have no choice but to take undesirable work such as at nighttime and on weekends to earn a high income in a short time for maintain their lives (Onishi & Ohnishi, 2019). Despite being in a vulnerable position in terms of employment, it is difficult to enter ADCC if the selection criteria score is low. Moreover, there is no ADCC that can accommodate diverse forms of employment. However, even if the score turns out to be low, there is a clear fact that "childcare is needed". Witnessing their difficulties, they cannot overlook this.

The childcare facilities targeted in this study were not stable or well-funded. Moreover, due to the chronic shortage of childcare workers, their childcare practice leads to financial difficulty ("if we take care of another 0-year-old child, we will need to employ another nursery teacher and it makes operation more difficult"). If the childcare charge is raised for operational reasons, the parents who used those facilities will no longer use them. As a result, it means that not only parents but also children cannot be supported. That is why even in difficult operational situations, the staff wanted to consider the best interests of the child and to care for the child in a safe and secure environment. One of the facility staff has quit her job at public preschool (C and D nursery teachers). One of the directors said "We are providing childcare that ADCC never do, and we are providing childcare for families whom the present childcare system in Japan cannot cover (B director). They are the very family we are supporting (C nursery teacher)." They are practicing childcare for those socially disadvantaged families. One parent who used the facility said to the staff, "As the facility allows children to play to their heart's content, my children say 'I'm looking forward to going there again' (C nursery teachers)." Of course, not all UDCC in Japan have such educational functions, however, there are few opportunities to reveal such efforts by staff working at UDCC.

I wonder if ADCC, which makes up the majority of ECEC in Japan, can provide the essence of childcare for everyone in need. Originally, the intent was that ECEC should be open to all children and their parents equally. However, if the ADCC continues to be a facility that meets national standards, there is no choice but to turn a blind eye to those who deviate from those standards for various reasons. It can be said that the idea of the founders of childcare, "delivering care to everyone in need," has been barely maintained by some childcare workers who cannot overlook it. Have Japanese ECEC researchers and childcare administrations faced this problem? Perhaps they have considered UDCC as an imperfect entity that cannot become ADCC, and have ignored, despised, or eliminated it. We may have explored the ideal way and system of childcare targeting only ADCC and considering only the majority who can access it, and neglected to deliver it to minorities who cannot access it.

Through the Salamanca Statement (1994), inclusive education has extended a range from people with disabilities to gifted children, street children or working children, children in remote areas and nomadic children and other children in poverty and children living on the frontier, and has been opened to all people in a disadvantaged situation. With inclusive education becoming widespread with the aim of the Inclusive Society, ECEC, which advocates "care," must include all people.

References

- Ikemoto, M. & Tateoka, K. (2017). A consideration of future perspective and correspondence in childcare needs. JRI review (The Japan Research Institute, Limited.), 42, 37‐65. (In Japanese)

- OECD (2007). Babies and Bosses‐Reconciling Work and Family Life: A Synthesis of Findings for OECD Countries. OECD publishing.

- Onishi, K. & Ohnishi, M. (2014). The educational function and welfare role of the unauthorized day care center (UDCC) in Japan (2): Research findings from interview with and observation at UDCC. 24th European Early Childhood Education Research Association Annual Conference.

- Onishi, K. & Ohnishi, M. (2015). The educational function and welfare role of the unauthorized day care centers (UDCC) in Japan (3): What are "Baby hotels" in Japan? 25th European Early Childhood Education Research Association Annual Conference.

- Onishi, K. & Ohnishi, M. (2016). The educational function and welfare role of the unauthorized day care centers (UDCC) in Japan (4): What do the parents expect of "Baby hotels" in Japan? 26th European Early Childhood Education Research Association Annual Conference.

- Onishi, K. & Ohnishi, M. (2018). How do "Baby hotels" in Japan support families with special needs: The educational function and welfare role of the "Baby hotels" in Japan (1) 28th European Early Childhood Education Research Association Annual Conference.

- Onishi, K. & Ohnishi, M. (2019). The study of children-wait listed and various needs of early childhood education and care in Japan; towards for research of the 'Baby Hotels users'. Bulletin of Gifu Shotoku Gakuen University Junior College, 51, 31-40. (In Japanese)

Acknowledgement: This article is a revised version of the work presented at the 20th Pacific Early Childhood Education Research Association International Conference held in Taiwan on July 12-14, 2019.

The research was supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Grant Number 17K04662.