* Titles and affiliations are as of the time of the conference.

Presented at Third International Conference of Child Research Network Asia (CRNA) held in Jakarta, Indonesia, September 25-27, 2019.

A Prescription for Play- Why play fosters social and cognitive development

Hello Jakarta! Thank you so much for inviting me to your conference for the Child Research Network Asia. Today's talk is about "How Play Fosters Social and Cognitive Development."

Play is everywhere. It is ubiquitous. Yet, play is under siege. What happened?

In 1981, a typical school child in the U.S.A. had 40% of discretionary time, for play. By 1997, this was 25%. Why? Since 2000, children have lost over eight hours of free play per week. Over 30,000 schools in the U.S.A. have dropped recess.

This sign was in a U.K. playground. It says, "No running, no jumping, no bouncing." New findings support the relative extinction of play. A 2009 survey by The Alliance for Childhood on 142 New York classrooms and 112 Los Angeles classrooms found that 25% of the teachers had no time for play. 61% of the New York teachers have no choice time. Instead they do test preparation, even for 5 year-olds.

The American Academy of Pediatrics was prompted to issue several reports. The first in 2006 was entitled: The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds. This was reaffirmed in 2012.

1. Defining Play

First, what is play? Free play is defined with a series of characteristics, objects, fantasy play, make believe, or physical play. It must be fun, otherwise it is not play. It should be active, not passive, without extrinsic goals. It is iterative, and when you repeat, something new and meaningful happens.

Guided play is slightly different. There is an extrinsic goal, to get learning from it. It has two forms. One, a planned play environment, with the playful experience carefully curated. The child directs what is going on. Two, where adults can enhance children's exploration and learning through playing along, asking open-ended questions so it is a conversation, rather than just a question that requires a single-word answer.

Free play is initiated and directed by the child. If initiated by an adult but the child directs, it is guided play. If the child initiates and the adult joins in, it is co-opted play. If initiated and directed by the adult, it is not play but direct instruction. Research suggests that these different kinds of play can be very important for coping, social learning, and academic skills. A 2017 report from Deborah Phillips of Georgetown University showed that a very rich curricular approach is possible in a quality early childhood education school, using playful pedagogy. Using guided play, children simply learn better.

2. Advantages of play

Free play has a protective factor, and has a lot to do with how young children cope with certain situations.

So-called executive function skills like flexibility, impulse control, focusing attention, and problem-solving are important. When young children are playing, they plan better, are more self-reliant, and less impulsive. In a beautiful study using the tools of the mind curriculum, Elena Bodrova and Deborah Leong showed you can create a curriculum to teach emotional regulation skills and executive function skills. A series of games was developed, and when children engage in playful learning*1 using well-designed tasks, their executive function improves, as does their math and reading scores on standardized tests. Megan McClelland devised a whole series of games for young children, like conducting an orchestra or beating a drum, involving self-regulation. In her book, "Stop, Think, and Act," games are shown to help young children do better in school, because in play they're learning attention, flexibility, impulse control, and problem-solving. Now in our own research, we found that when adults read from a book like "The Knight and the Dragon," children are very engaged. We highlight vocabulary, new words, like galloping, or the shield that the knight might hold as they fight their enemies. Then we give the kids a chance to be in one of three conditions. One is free play, and the other two are more like guided play or directed play. In the free play they can do what they want with the figurines, the shield, or the horse, or the knight. In guided play or directed play, we give them script hints. The child is still in charge, but with more structure.

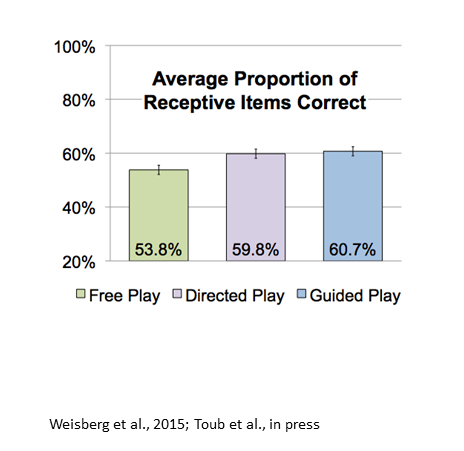

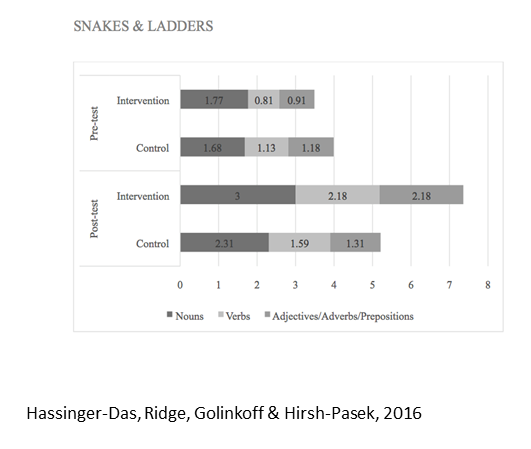

This graph shows about 60% of young children in directed and guided play learn most vocabulary words, whereas in free play, it is about 53%. So, when you have a goal in mind, a playful pedagogy through guided play can help young children learn things like vocabulary. In our most recent study, we expand to group games, with a music or a digital condition. We found that children learn vocabulary through play as they do through flash cards or definition and review. One such game was Snakes and Ladders. They either play the board game as they read the block or review the words through flash cards activity. We found that the play condition works better than the review and flash cards which is mainly rote learning. It is passive, it is not active learning, nor engaging.

As you can see in figure 2, our pre-test results were almost the same for the intervention group and control group, but in our post-test, the playful intervention was better than the controlled group, which is the group of kids who used flash cards.

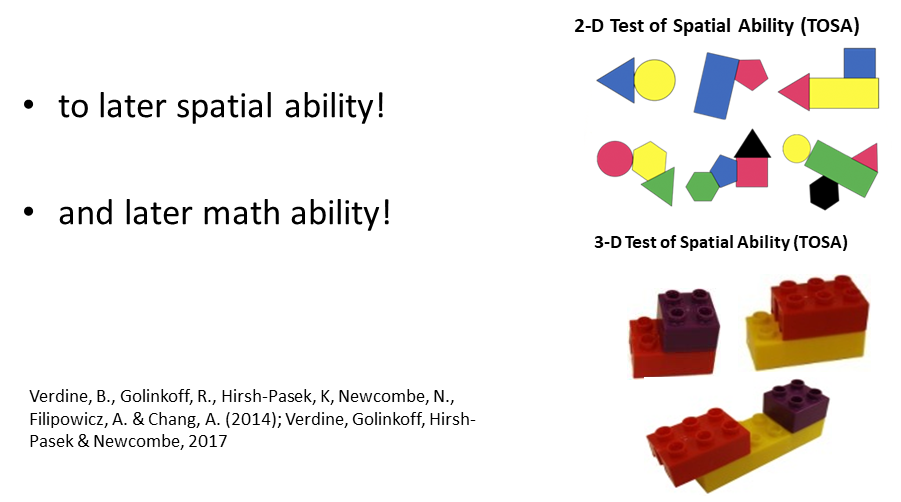

This is also true for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) learning. Playing games such as finding patterns, dividing and sharing candy, sorting trail mix into the nuts and candy, "I spy with my little eye a rectangle" helps children learn shapes. These games engage children with STEM in ways unattainable in non-playful activities. Our research also focused on block play, which is very important for spatial and mathematical learning. Spatial language such as "in," "around," "through," "under," are used more frequently in guided play using blocks, than in free play.

These kinds of words are important for later spatial learning, and for later mathematical ability. In our study, we conducted 2-D and 3-D tests of spatial ability(Figure 3). Children who can do well on these tests at age three are better prepared for school at age five.

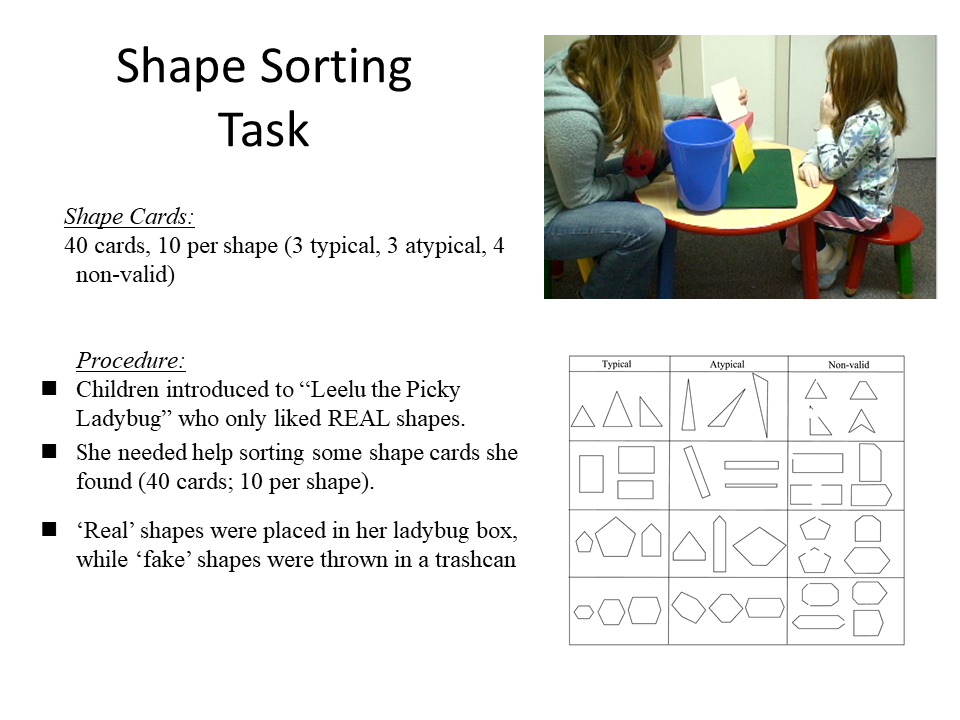

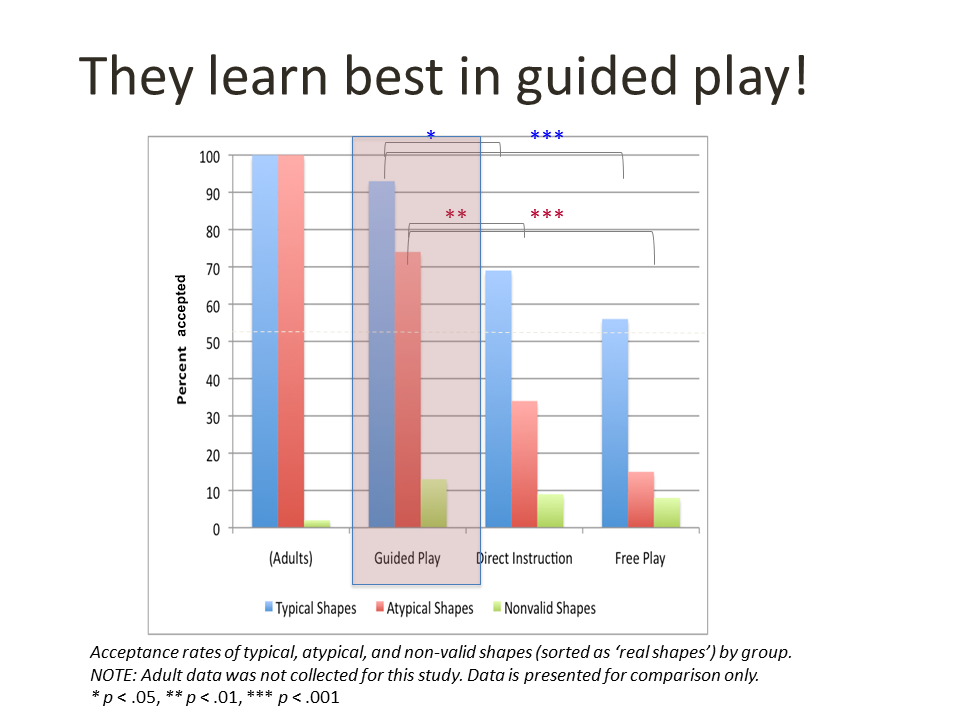

Finally, we did a geometry study, to figure out if it helps children learn the criterial features of shapes like triangles. It is obvious that a triangle is a shape with three angles and three sides whether it is on its side or with its point upright. Yet in every curriculum we reviewed, the point was always upright. So, if a child only learns triangles with the point upright, they would think they know all about a triangle. In the direct instruction, we held up the triangle and said, it is a triangle with three sides and three angles. In the exploratory free play, we just let them play with triangles, without giving any guidance in any way. Then they did the shape sorting tasks as shown in figure 4.

There were 40 cards, 10 per shape. Three typical, three atypical, and four that were all invalid. Could they indicate the real triangles? Isosceles triangles, right triangles, equilateral triangles? Did they know that they were all triangles? Even if turned, will they still be triangles? And did they know some things with the point upright were not triangles? The answer is here, in figure 5.

Why might playful learning support learning? Here are some hypotheses:

Big Idea 1. It involves "active, engaged, meaningful and socially interactive learning" and that is how humans learn best! (Chi, 2009; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015)

Big Idea 2. Guided play is like "constrained tinkering" that lessens the "noise" and prioritizes some hypotheses over others. Offers a chance for hypothesis testing. (Parish-Morris et al., 2014; Tare et al., 2010; Uttal et al., 1997)

Big Idea 3. Guided play creates a mise en place or positive disposition for learning and exploration (Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & McCandless, 2014; Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2016). It creates a set up, as in cooking we set everything out first, and get more engaged, into the flow and therefore learn more.

Big Idea 4. Playful learning is joyful and positive emotions help children learn! If it is positive, kids learn better.

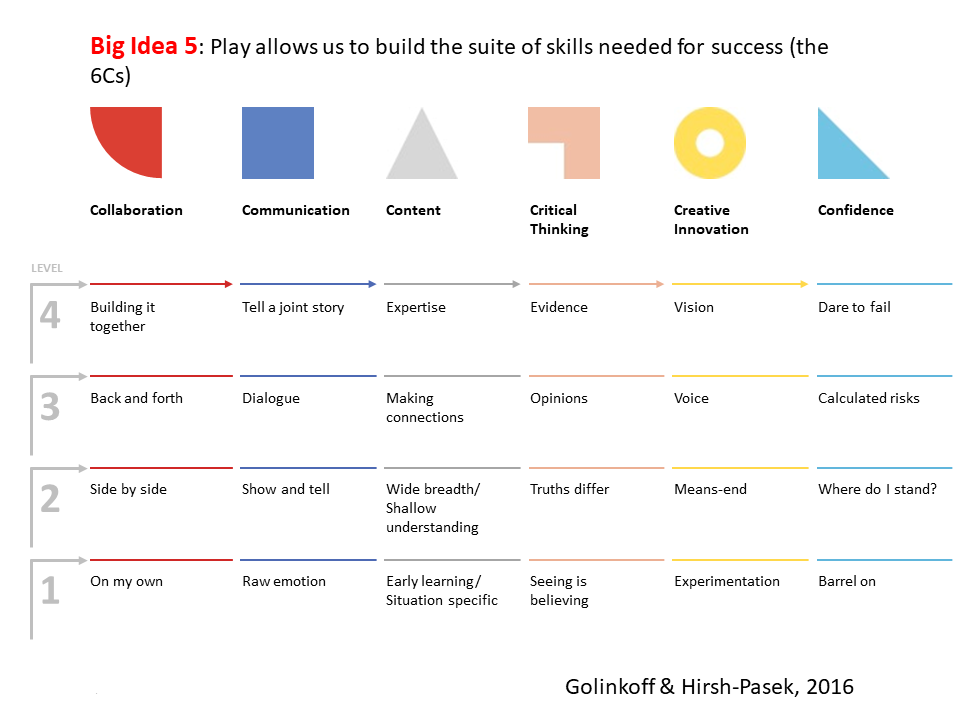

Big Idea 5. Play allows us to build the suite of skills needed for success (the 6Cs).

Play helps us learn to get along with people, how to communicate and hold longer conversations, learn content like STEM, or reading, causality, critical thinking. Critical thinking like which block makes that box laid up? How to put that together? To make that work? Play helps us with creative innovation. In our book "Becoming Brilliant*2," we present the argument for 6C collective skills.

3. What we can do to foster playful learning

Theory is fine but how do we use it? I will tell you about a traditional school at West Chester, Pennsylvania where 5 year-olds would sit and learn their math and their STEM skills. Then they adopted a playful curriculum model. A little girl would go through the weather of the day, how a high or low front might mean rain, using words like forecast, prediction and weather report. Remarkable! In another class, when telling fairytales, they would do a mash-up between the Three Little Pigs and Little Red Riding Hood, their original version.

Encouraging play at home, that is the play prescription. There are a lot of programs at pediatrics offices where we reach out and give children books, so they start to see the value of reading, the STEM, the critical thinking, the collaboration and the communication.

Dr. Alan Mendelsohn at NYU showed we can help children learn to play, and parents facilitate it. In under-resourced families, children become better players, and do better in school. Home visitors can use the same techniques of taking toys to the family, helping under-resourced families learn the power of play.

Finally, in our own research, we have focused on the opportunity of play in the community. Full-time school takes up only 20% of children's waking time. Children spend 80% of their time outside of school. How can we augment that? The answer is: With a playful learning landscape. A simple bench can morph with other ordinary spaces to encourage mental gymnastics. Here are some examples.

The first example is the Ultimate Block Party, which was a series of 28 science-inspired activities in Central Park, New York City, held in 2010. Over 50,000 people attended. Parents who visited more than 3 activities, understood the connection between play and learning.

Example two, is our Supermarket Study. We put up signs in supermarkets in an under-resourced neighborhood to see if they increase caregiver-child language interactions.

I'm a cow, I have milk. What else comes from milk? In these communities, the families spoke 33% more to their children and so produced vocabulary growth. Repeating with STEM signs gave the same result. Children use more number words, which will relate later to how they do in math.

Example three, is the Urban Thinkscape. In a West Philadelphia community, Brenna Hassinger-Das, and Itai Palti, an architect, transformed bus stops into a playful learning space. When they asked people if they wanted puzzles in their neighborhood, and what they would like to put in the puzzles, they wanted to celebrate Martin Luther King.

As a result, 35% more families started having longer conversations with their children, 34% started to use more number words, shape words, color words because they were available at the bus stop.

Example four is the Parkopolis, the life-sized board game for early mathematical skills and scientific reasoning. It was invented and implemented in parks by Andres Bustamante, a student at the University of California in Irvine. The dice was designed to have whole numbers and fractions, from which we found the kids and adults used more fractions. If you rolled six and a half and then a three and a half you had to know to go to space ten, where an activity waited. Through the experience of Parkopolis, 47% more adults used math language, 79% of the children started using math words, even fraction words.

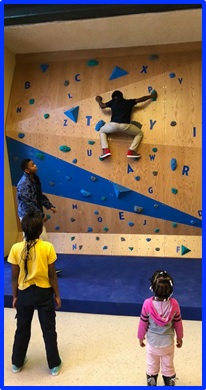

Example five is the Playbrary. This is a climbing wall in the library with letters so kids can make words as they climb. Or they can make their own seating by taking the tangram puzzles out of the library stacks and put it on the floor to use as they read. Results showed spatial, color, and letter language increased by 44%, and adults' and children's use of technology decreased by 38%. In fact, 3 times more people signed up for the library registration.

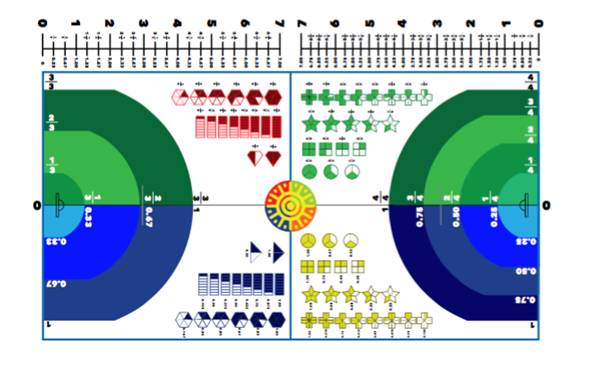

The last example of playful learning landscape, is the Fractionball, which was designed to change the basketball court for middle schoolers. Shooting from various positions scores three-quarters, one point, a half, to add-up to a particular number and see how close they can get to another number. Along the side they can keep their scores.

These are all parts of the playful learning landscape. We even created a playbook, which you will find at kathyhirshpasek.com.

To summarize, it might be time to write a play prescription. Play helps children cope, socialize, and learn. Play is not the opposite of work. It is the work of young children. Children need play even in refugee camps, or in war zones.

Thank you for listening. Thank you to our funders and Dr. Roberta Golinkoff, my co-worker for forty years. Thank you to all the families in the research shown today. I hope you now understand why I think play is so critical.

Comments from the Moderator

Regarding play, schools and even parents today are not really letting children play. They are even restricting children from playing. They do not know that play actually leads to learning, but it's the children's job to play. There is no need for toys. Clothing, shoes, anything around them can become a toy.

Playing is learning. According to Kathy's talk, free play on their own does not enough give enough stimulation to children. The use of language is important. If teachers or parents around them can give them a shower of words, describe what they are doing.

Guided play is better compared to free play. Play makes them happy, with less stress, and is very important in children's life. It happens in all stages of childhood. That's what Kathy talked about. Play is essential in children's life.

- *1 For more information on playful learning, see playfullearninglandscapes.com.

- *2 Golinkoff, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming Brilliant: What Science Tells Us About Raising Successful Children. Apa Life Tools.

-

Reference:

- Hassinger-Das, B., Ridge, K., Parker, A., Golinkoff, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Dickinson, D.K. Building Vocabulary Knowledge in Preschoolers Through Shared Book Reading and Gameplay. Mind, Brain & Education, Vol.10, Issue2, 2016.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., Toub, T.S., Hassinger-Das, B. Playing to Learn: Vocabulary Development in Early Childhood, Research, Policy, and Practice 2014 Conference Program, April 2014.

- Phillips, D., Lipsey, W. M., Dodge, K., Haskins, R., Bassok, D., Burchinal, M.R., Duncan, G.J., Dynarski, M., Magnuson, K.A., Weiland, C. Puzzling it out: The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-kindergarten effects, A consensus statement. REPORT, Brookings Institution. April 17, 2017.

- Ridge, K.E., Weisberg, D.S., Ilgaz, H., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. Supermarket Speak: Increasing Talk Among Low-Socioeconomic Status Families, Mind, Brain, and Education, Vol.9, Issue 3, 2015. P. 127-135.

- Verdine, B., Golinkoff, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Newcombe, N., Filipowicz, A., Chang, A. Deconstructing Building Blocks: Preschoolers' Spatial Assembly Performance Relates to Early Mathematical Skills, Child Development, May/June 2014, Vol 85, No. 3, P.1062-1076.

Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek

Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek