* Titles and affiliations are as of the time of the conference.

Presented at Third International Conference of Child Research Network Asia (CRNA) held in Jakarta, Indonesia, September 25-27, 2019.

What's New in Language Development and Why Should We Care?

Today I will talk about "What is New in Language Development and Why Should We Care?"

It is about how high quality language environments create high quality learning environments. How do we turn adorable babies into fully productive adults? We bathe them in language and stimulation from birth, and nurture their social and emotional lives. I emphasize language because it is linked to success in school and health outcomes. Language skills come from high quality language environments where adults and children engage in conversation on a shared topic, before the child utters a single word.

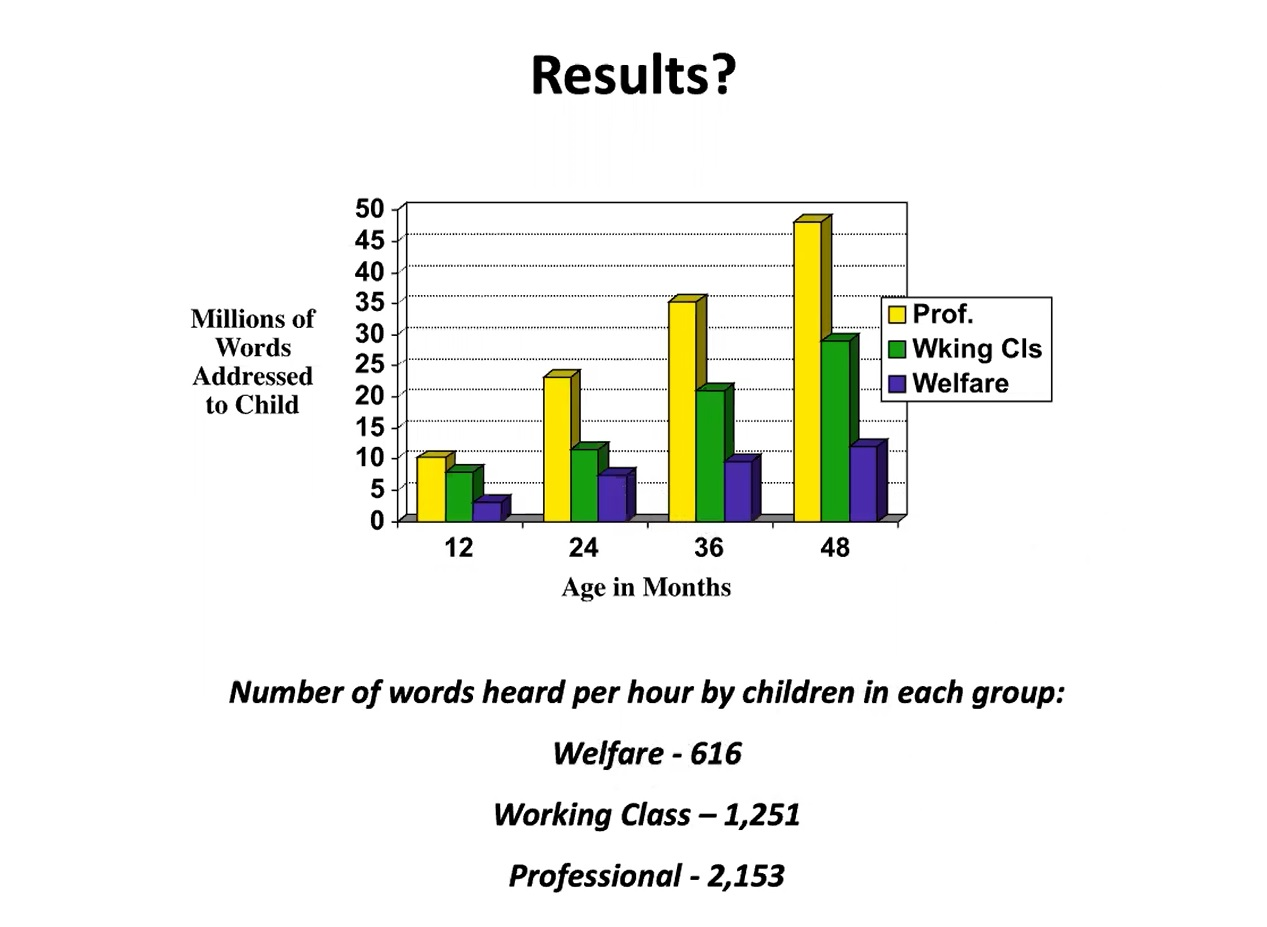

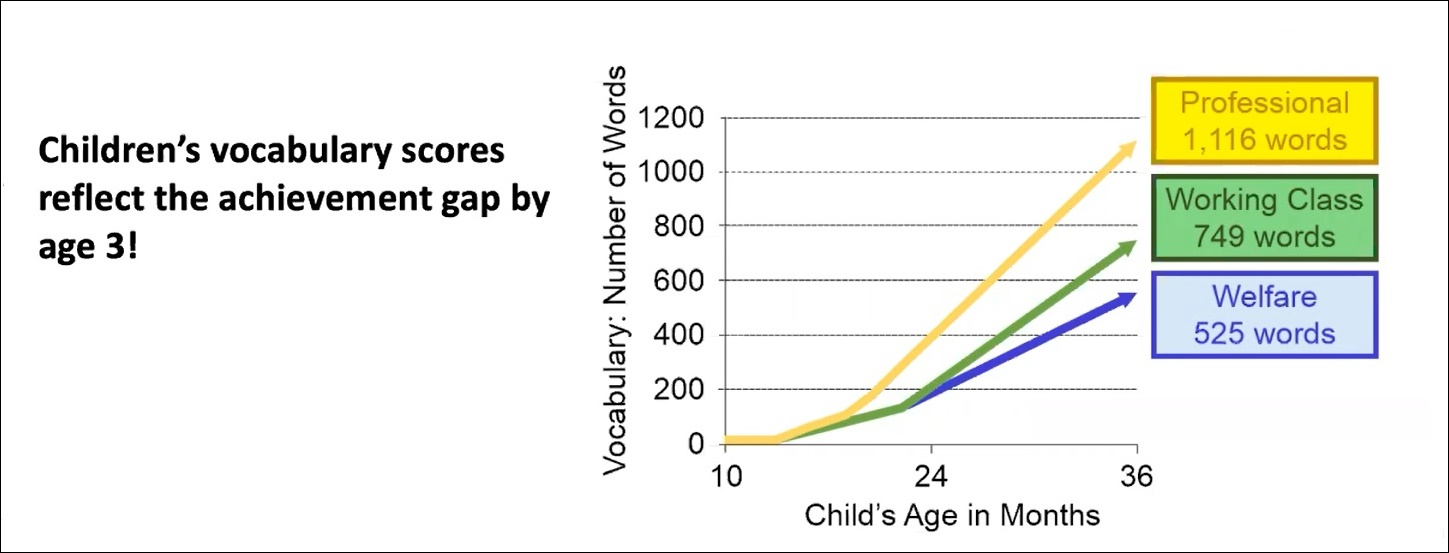

The 30-million word gap came from Hart and Risley in 1995 who examined language input to children from welfare, working class, and professional families. They recorded the speech directed to children and found out the number of words per hour in each group was drastically different (See Figure 1). The yellow bars represent professional families, green bars working class families, and purple welfare families. The Y axis shows the millions of words addressed to the child over 12, 24, and 36 months. It shows that kids in professional families hear much more language than in the other groups of families. And the verbal interaction in welfare families hardly increase at all even as the child grows older. It shows that children in welfare families hear only 616 words per hour compared to working class families who hear double that and professional families who hear double that!

The significance is that children's vocabulary scores reflect the language they hear which explains the US achievement gap. This early language makes a huge difference for the language that they learn later. Vocabulary at age 3 also correlated to reading comprehension scores on a comprehensive test of basic skills at age 9 and 10. By second grade, middle class children know 6,000 root words, but lower income children know only 4,000, which suggested that they are 2 grade levels behind.

To understand a text you must understand the vocabulary used in the sentence structure. Building strong language skills requires a fine quality preschool environment, which includes high quality talk to kids. Currently in the USA, teachers spend less than 19% of their time talking to individual children.

A recent paper of ours suggests that language at school entry, kindergarten in the U.S., is the single best predictor of school outcomes, in reading, math, social skills, and later language in grades 1 and 3. It also predicts scores from grades 3 to 5. Language is the single variable that affects achievement in these school subjects.

Today my talk about creating high quality language environments will be in two parts. The first part of my talk is on the six principles of language learning.

Six Evidence-based Principles of Language Learning that Support Reading

Research tells us that there are six principles of language learning that can be used to enhance language outcomes and the foundation for reading.

- Children learn what they hear most.

- Children learn words for things and events that interest them. Things like the light switch, their toy, the doggy. Not for things like death and taxes.

- Interactive and responsive environments build language learning. You cannot learn language just from listening.

- Children learn best in meaningful context, when what's happening around them is encapsulated in the language people use.

- Children need to hear diverse examples of words and language structures. Talk to them in a way that takes their interest into consideration. Use words and sentence structures that they might not know.

- Vocabulary and grammatical development are reciprocal processes, that happen mainly at the same time.

First, children learn what they hear most. What is the evidence?

The Hart and Risley findings are the best possible evidence. What children hear feeds directly into how much they learn. If they do not hear enough vocabulary, they will not say the words. How could they?

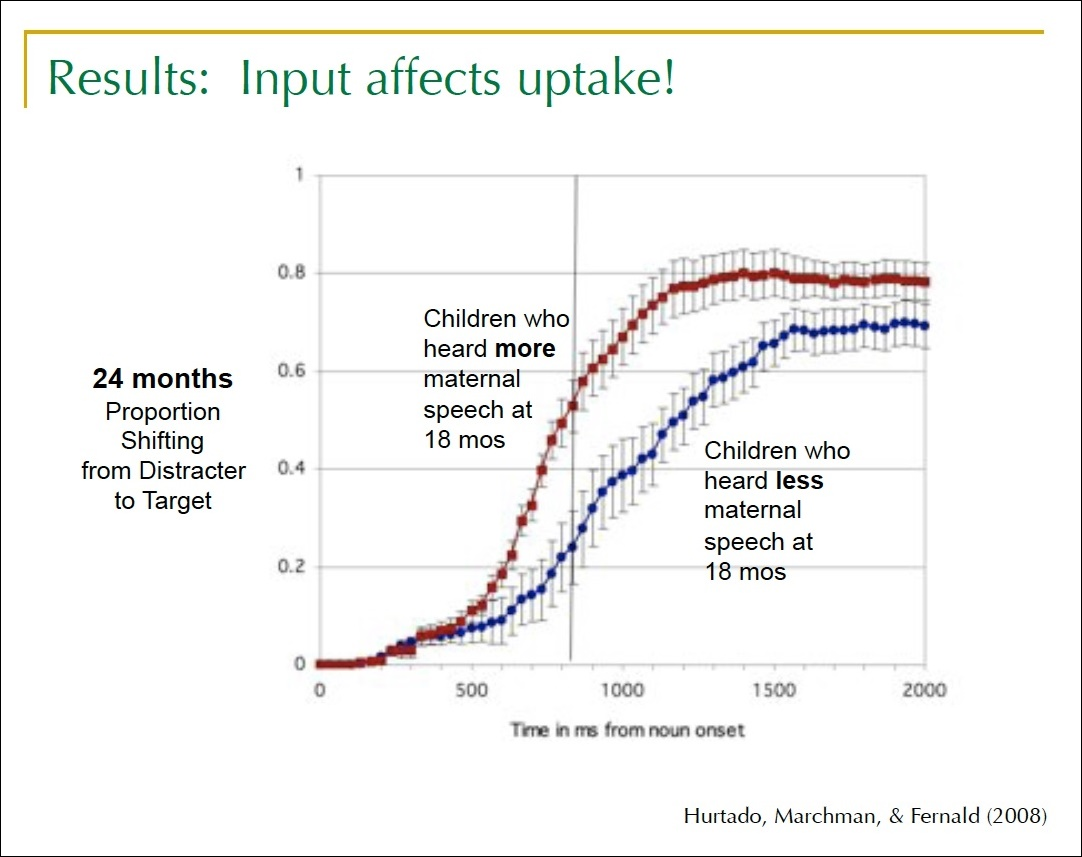

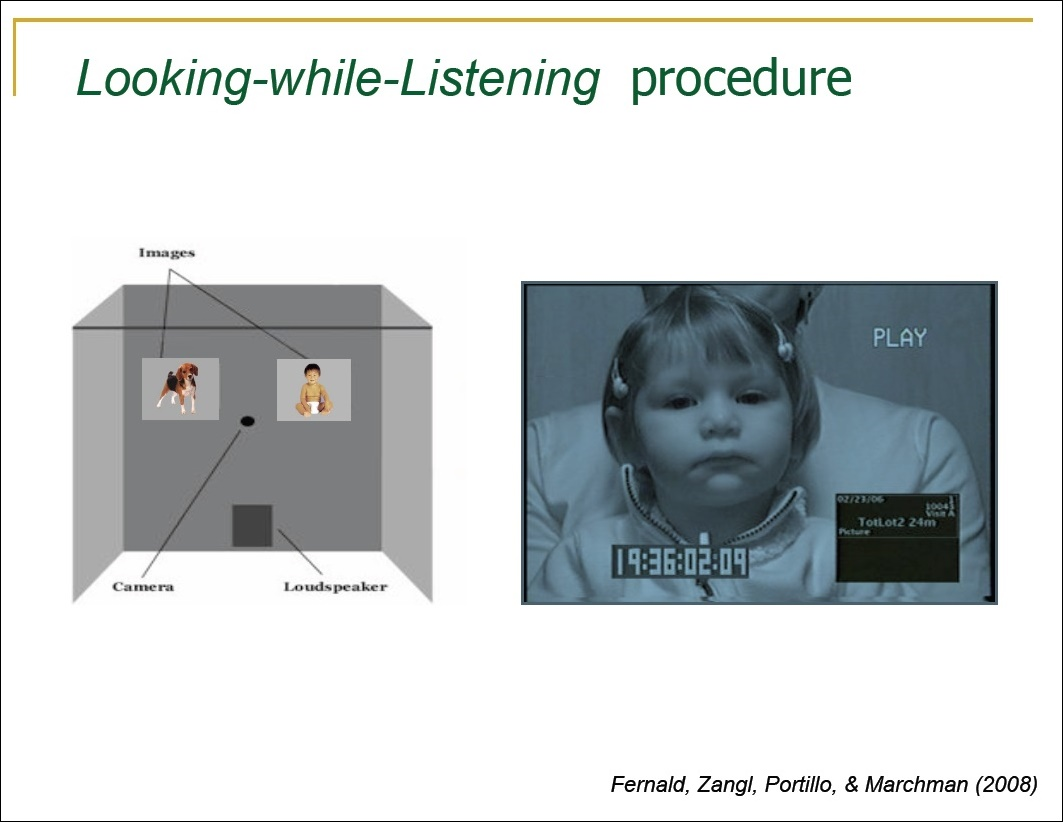

The amount of speech is important for statistical learning and for how fast they resolve the incoming auditory signal. Aslin, Saffran and Newport reported that the language babies hear matters because they do statistical analysis on it to find patterns of sounds and words. Fernald at Stanford University discovered in her study that if you show a child two images and track how long it takes them to look at a named image, the time will vary depending on age (Figure3). When they hear lots of language, their response is quicker (Figure 4). At school, if you're slow at processing what your teacher is saying, you will fall behind. The amount of language input affects children's processing efficiency. The red line in the graph shows 18 months-old children who heard more language, the blue line children who heard less. A remarkable difference can be seen at how rapidly children at the red line look at the target compared to the children who heard less language at 18 months.

The second principle is, children learn words for interesting things and events.

In a study conducted in the US, over 75 babies were tested with a series of objects and attached made up names. Could they remember the names? A series of questions were asked. Researchers then tracked the baby's eyes to engage their responses. They found that infants can pair words with objects. But they also discovered babies only associate new words with flashy, interesting objects that attract their attention, not with boring, dull objects.

The third principle is, interactive and responsive environments build language learning. This means it is important to talk WITH children, not AT them. Mothers should expand what their child says and does. If the child says, "Daddy car," the parents can say "Yes. Daddy is driving home in his car." It is also important to notice what the child finds interesting and comment on it. If the child is staring at something on the wall, talk about what is hanging on the wall. That is what the child wants to learn about. Then using a label that goes with it. "Oh, it is a picture of a tree." Asking questions rather than making demands is important.

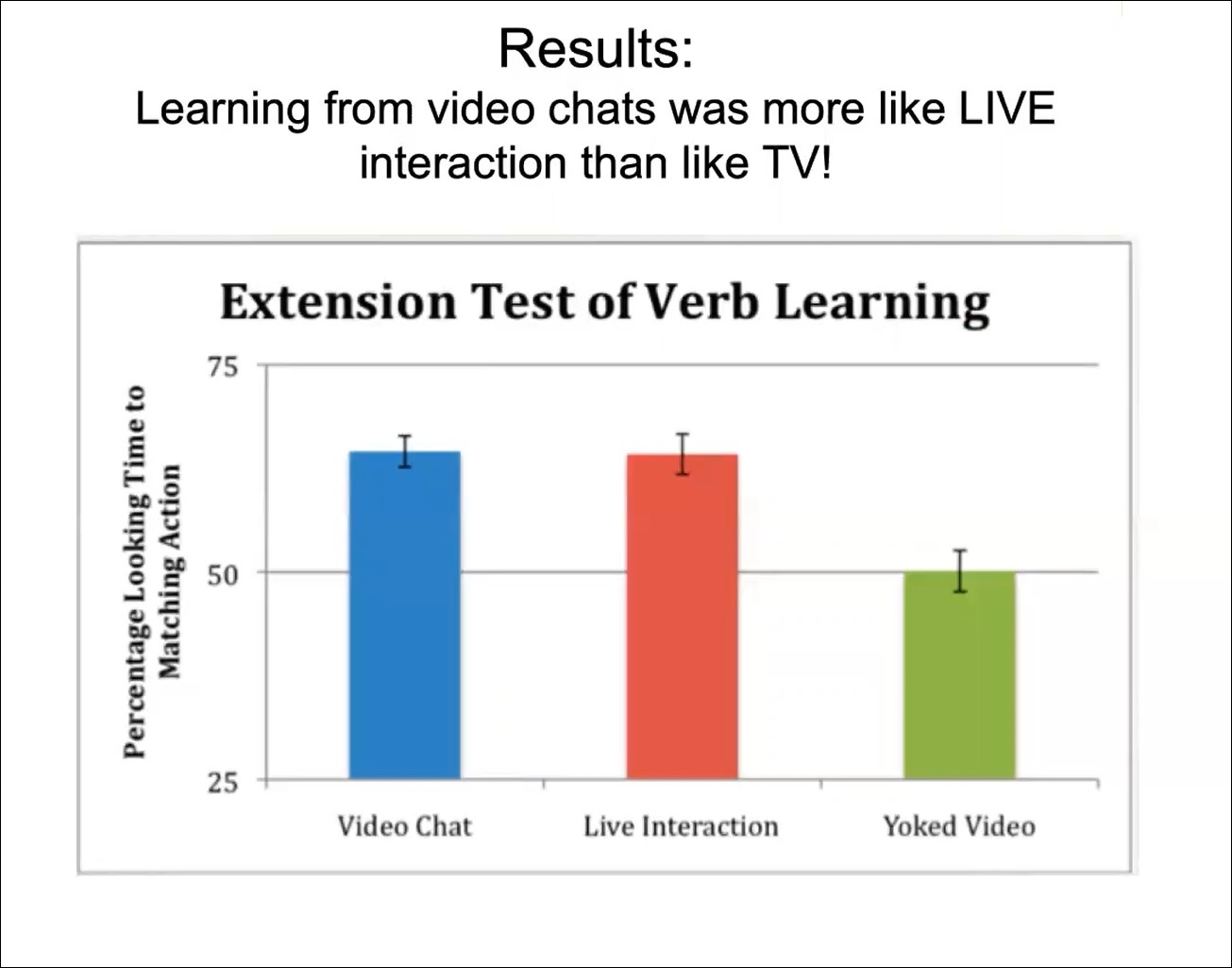

In another study, we used video chat with 24 to 30 months-old babies to see whether social contingency might support word learning. Toddlers were exposed to new words under three conditions: Video chat, which is responsive and contingent on what the baby is doing, but still two-dimensional, flat; live interaction training, which is responsive to the baby and contingent but also real life, three-dimensional; yoked video training, where the subject children saw a pre-recorded video of another child, which was neither responsive, nor contingent on what the child does.

Can children learn new words from video chat? Yes, video chat is more like live interaction than TV.

Figure 5 shows the results of an extension test of verb learning. You will see the blue column shows that video chat interaction leads to word learning like live interaction. But only if it was contingent and responsive.

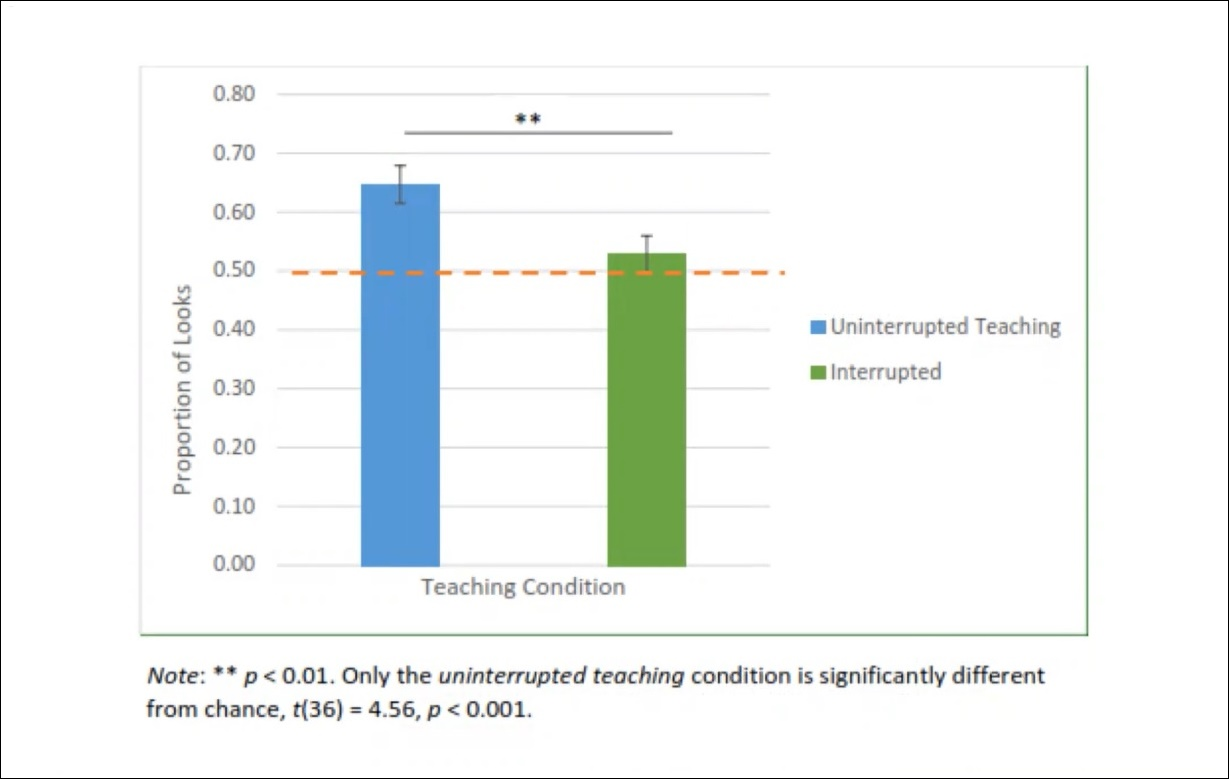

What happens if we break the interaction with the use of a cellphone?

In the study, we gave the mothers with two and a half year old babies who came to the lab a cellphone that would ring, so they could tell us how the procedure was going. By calling the cellphone, we interrupted the interaction with the child in the middle of the first word, or we interrupted it between words.

Figure 6 shows that being on a cellphone call in the middle of an interaction disrupts the child's word learning --i.e. the green bar. When the teaching is not interrupted, the child will learn the new word, but if the teaching is interrupted, it is like the child says, "you break our social contract. I am not learning that." The fourth principle is, children learn best in meaningful contexts. From the study we have done in our lab, we found out that children gain a richer vocabulary through playful learning where the information is meaningful to them and they are reacting to the object than they do through direct instruction, where we just try to teach them words outside a situation where they are actively involved.

Principle five is, children need to hear diverse examples of words and language structures. Their vocabulary performance in kindergarten and later in 2nd grade is related to the occurrence of sophisticated lexical items heard at age 5. The amount of sophisticated words that children hear at home, which they might not hear at school or in picture books, at the age of five predicted 50% of the variance in children's second grade vocabulary. The sixth principle is; vocabulary and grammatical development are reciprocal processes. They are "developing in synchrony across the first few years of life." Kids don't have to amass a ton of vocabulary before learning the rules of sentence construction. They learn both at the same time. With bilinguals, the number of English words known predicts their English syntax or grammar and the same with Spanish. These things work together; as you learn vocabulary, you learn how to make sentences. For example, in our study, we asked the mother to use an invented word. So the mother said, "What am I doing? I am blicking the baby." She uses the nonce word like a verb, herself as the subject of the sentence, and the baby as the object. Kids at a certain point can use the grammar, the syntax that they hear around the word to predict what part of speech it is, then get something of its meaning.

These principles are things we do all the time with kids. Research in language development supports it and we can maximize their use in our classrooms and homes by developing exercises on ways to use them. These principles hold with learning one language or two.

Implications and Outreach

The second part of the talk is on the implications of the findings and outreach.

We can use these principles in a conscious way to practice support on our children's language learning.

We want to 'langualize' environments by putting these six principles into practice, to systematically manipulate them and change language trajectory for kids starting early. We do not want to wait for them to fall behind. We want to facilitate language even before their first word comes out. These language strategies are learnable and malleable. Caregivers, teachers, parents can learn how to talk to their kids in light of these principles.

There are a number of examples on how we can change the language learning at an individual and family level, at a classroom level, or community level.

In our book, Becoming Brilliant, we prioritize language as part of the 6Cs, essential for children's success in the 21st century.

Together with Collaboration, language plays an important part of Communication, Content, Critical thinking, Creative innovation and Confidence.

The curriculum for children needs broadening in the 21st century. Part of that is helping them to listen, speak persuasively, and write. All rooted in language.

My colleague, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and I, and Judith Schickedanz, wrote the California preschool curriculum. The framework in language and literacy area shows how these principles come alive.

Our research shows ways we can incorporate vocabulary learning by having them read with replicas around the storybook they are reading, and by having a teacher encourage them to use the words, act them out, and make meaning with them.

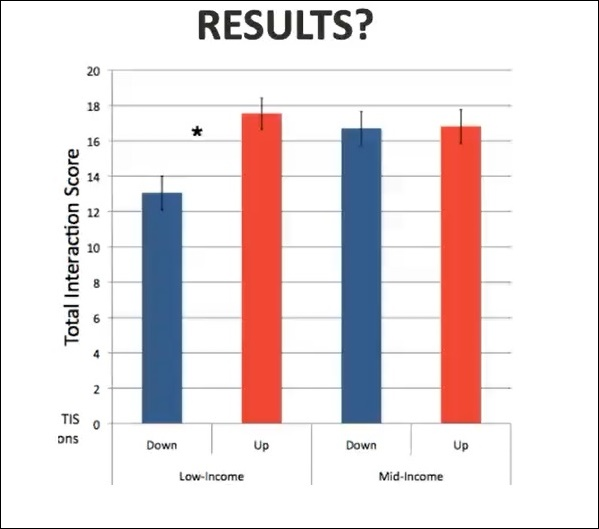

More quality talk can be induced using the six principles in our community. How can a supermarket help kids learn language? We devised signs to trigger parent-child conversations, not a highly technical or very expensive task, and distributed them around the supermarket. Observers with white coats and clipboards like supermarket staff quietly charted the amount of talk between parents and children. This was done in low income and middle-class communities.

The blue bars represent when the signs are down in the store, red when the signs are up. On the left are the results from the low-income supermarket. There is a huge difference, a 33% increase in the amount of language conversed between parents or caregivers and their children when these signs are up. The right hand, shows the results from a middle class supermarket. Parents babble to their children all the time, so they don't need signs. Thus there is no difference when the signs are up or down in the middle-class supermarket. A 33% increase in language is impressive. So we encourage supermarkets and pharmacies, any place that parents go, to put up things that increase talk between kids and parents. We have more supermarket projects being conducted in Tulsa, Oklahoma, South Africa, and Ohio.

If we build a strong language foundation by using these 6 principles in our classroom, our home, our community, we can help children be ready to read by age 5 and 6 and increase the quality of all our nations' preschools.

I would like to say thank-you for my collaborator, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, the support grants for our research, the best lab ever, and the parents and kids who made it possible.

Thank you all for allowing me to talk to you today.

-

Reference:

- Hart, B., Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Maryland: Brookes Publishing.

- Fernald, A., Zangl, R., Portillo, A.L., & Marchman, V. A. (2008). Looking while listening: Using eye movements to monitor spoken language comprehension by infants and young children. In Sekerina, I.A., Fernandez, E.M., & Clahsen, H. (Eds.) Developmental Psycholinguistics: On-line methods in children's language processing(p. 97-135). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/lald.44.06fer

- Hurtado, N., Marchman, V. A., & Fernald, A. (2008). Does input influence uptake? Links between maternal talk, processing speed and vocabulary size in Spanish-learning children. Developmental Science, 11, F31-F39.

- Roseberry, S., Hirsh‐Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R.M. (2014). Skype Me! Socially Contingent Interactions Help Toddlers Learn Language, Child Development, Vol. 85(3), P. 956-970.

- Weizman,Z.O., Snow, C.E. Lexical Input as Related to Children's Vocabulary Acquisition: Effects of Sophisticated Exposure and Support for Meaning. Dev Psychol . 2001 Mar;37(2):265-79. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.265.

Roberta Golinkoff

Roberta Golinkoff