Presented at the International Symposium on Children's Welfare and their Rights held by the Japanese Society of Child Science and

Child Research Net

Main Hall, Okayama Head Office of Benesse Corporation

October 14, 2013

The 'adulteration' of adolescence?: Balancing the rights of adolescents to autonomy and protection in the UK

Where are We Now? - "hands off approach to state intervention"

Enlarge

EnlargeSo where does that leave us now? Well, the hands off approach to state intervention in family life, embedded in the historical and universal establishment of the family as the basis of society, appears to be endorsed in international law. The UNCRC provides for parents to take primary responsibility for the upbringing and development of the child - although it also stresses the duty on states to support parents in their child-rearing responsibilities. The European Convention on Human Rights (which was created in response to atrocities committed against particularly the Jewish people in the second world war, and is part of UK law) protects parents against unlawful and unnecessary state intervention in family life.

UK Context

Enlarge

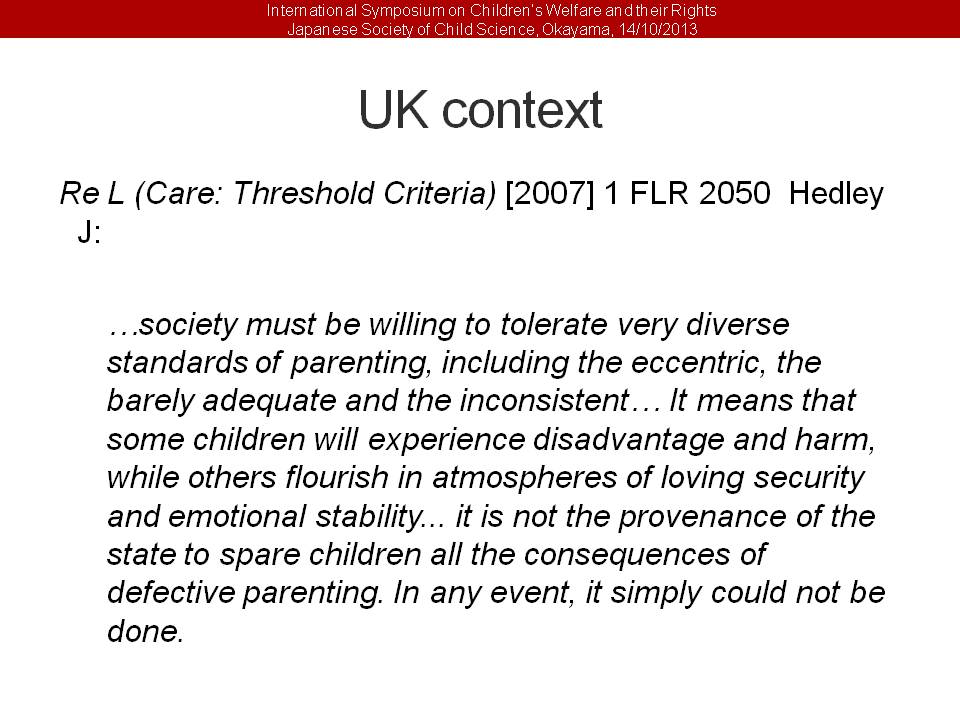

EnlargeIn the UK, the law acknowledges the consequences of this for vulnerable children and young people, as in this renowned but rather disturbing quote from Mr. Justice Hedley in recent years. In countries with high inequality such as the USA and the UK, it also means that children will have very different experiences of parenting and there will be very unequal consequences flowing from that - because we know that poverty increases the stress of parenting significantly.

Where are We Now? - change in inter-generational contract

Enlarge

EnlargeThe demise of the authoritarian state and family has, at its best, led to improved inter-generational relationships, in which children are valued members of the family and of the state, whose views deserve respect. It has also encouraged respect for and tolerance of cultural and social diversity. Importantly, children also have greater opportunities to contribute to decisions affecting them. Many commentators argue that the demands of modern democratic society are such that children require the skills to make judgements and exercise responsibility at ever earlier ages and that a successful transition to adulthood requires opportunities to practise decision-making - an idea Jane Fortin describes a 'dry run' at adulthood.

At its worst, however, so-called liberal notions of parenting have been heavily criticised for resulting in over-indulgence and inadequate discipline of children, in the name of individual freedoms. At the same time, the traditional structures of society and community have come under increasing pressures as cultural diversity increases, working mothers and single parenting become the norm and greater mobility reduces support from the extended family.

Progress

Enlarge

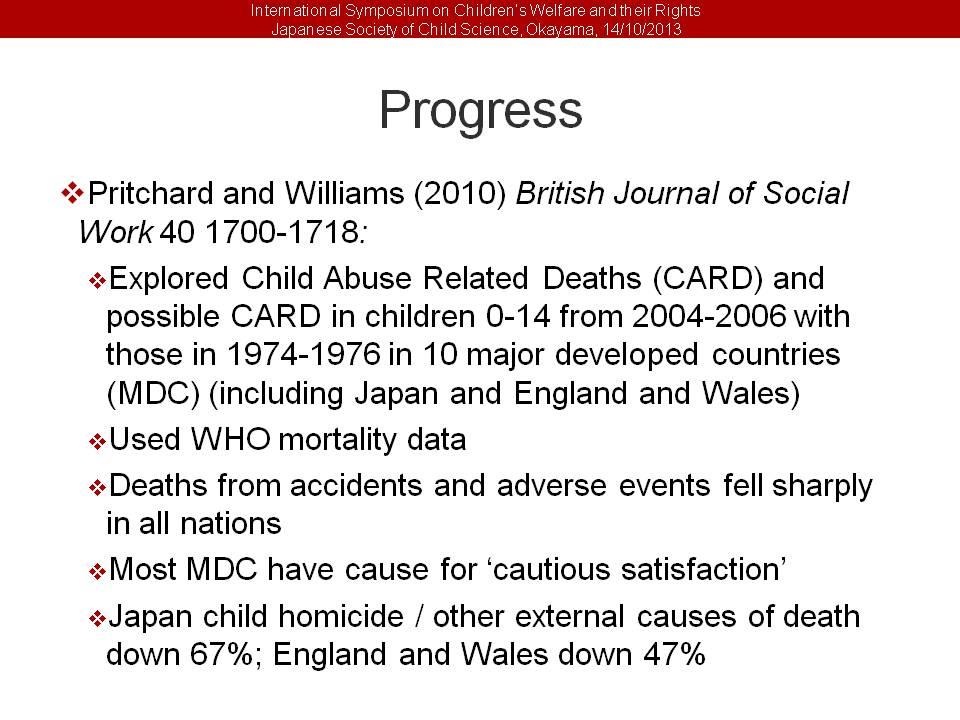

EnlargeIt should not of course be forgotten that much progress has been made as a result of the attention focused on children's welfare and their rights in the last century and in particular, there is much to celebrate in the 50 years since Dr. Kempe and colleagues coined the term 'battered child syndrome' in 1962 and drew attention to familial child abuse. Acknowledgement of children as holders of rights which may conflict with those of their parents together with greater respect for children's views has arguably contributed to our ability and willingness to penetrate the family unit and confront the issue of child maltreatment within the home environment. It is extremely difficult to measure the prevalence of child maltreatment in any jurisdiction, never mind to compare across jurisdictions, because of different and changing definitions of maltreatment and methods of measurement, coupled with the fact that awareness, particularly amongst professionals, has led to higher levels of reporting. However, a number of indicators suggest that we have made significant progress in relation to identifying and protecting abused children, including this report, which compared WHO mortality data from 10 major developing countries to challenge media perceptions in the UK that the child protection system is failing.

The report used the 1974-76 figures because in the UK, the death of Maria Colwell at the hands of her parents drew attention to 'battered child syndrome' and sparked the birth of the modern UK child protection system. To ensure as true a picture as possible, the report included deaths from 'other external causes', the WHO category for circumstances in which it can not be determined whether the death was accidental or a result of self-harm or assault. It concluded that deaths from accidents and other adverse events fell sharply in all nations and that most major developed countries have cause for 'cautious satisfaction' in relation to child protection. In particular, it is estimated that deaths from homicide or other external causes fell by 67% in Japan and 47% in England and Wales over the 30 years under review.

Enlarge

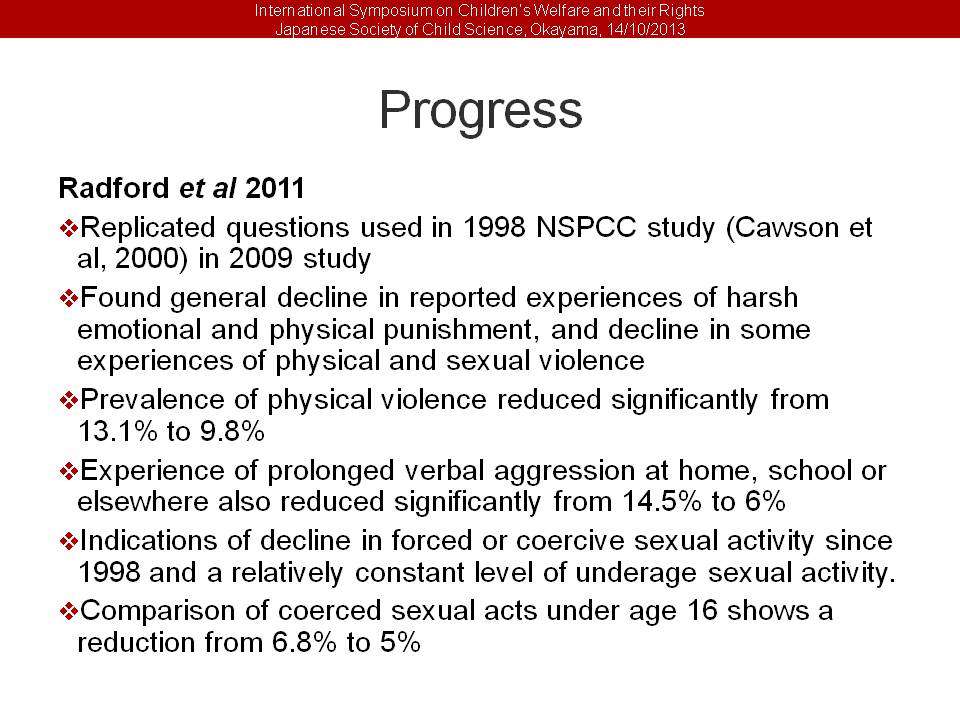

EnlargeAnd in the UK, there appears to be further evidence that changed attitudes to children and young people by the adults that care for them has resulted in warmer intergenerational relationships and a reduction in physical punishment and violence in the last decade. The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children replicated questions from a 1998 survey of young adults in 2009. They found a general decline in reported experiences of harsh emotional and physical punishment, and a decrease in some experiences of physical and sexual violence. In particular, the prevalence of physical violence reduced significantly from 13.1% to 9.8% and children's experience of prolonged verbal aggression at home, school or elsewhere also reduced significantly from 14.5% to 6%. The research also showed indications of a decline in forced or coercive sexual activity since 1998 and a relatively constant level of underage sexual activity. Comparison of coerced sexual acts with children under the age of 16 showed a reduction from 6.8% to 5%.

'Adulteration' of childhood?

Enlarge

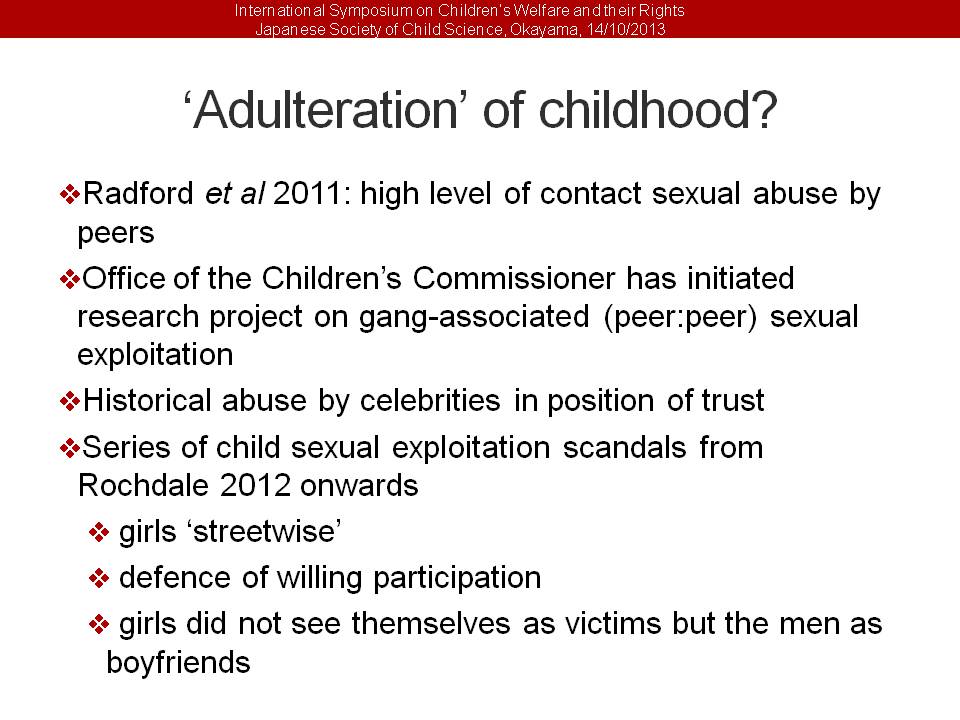

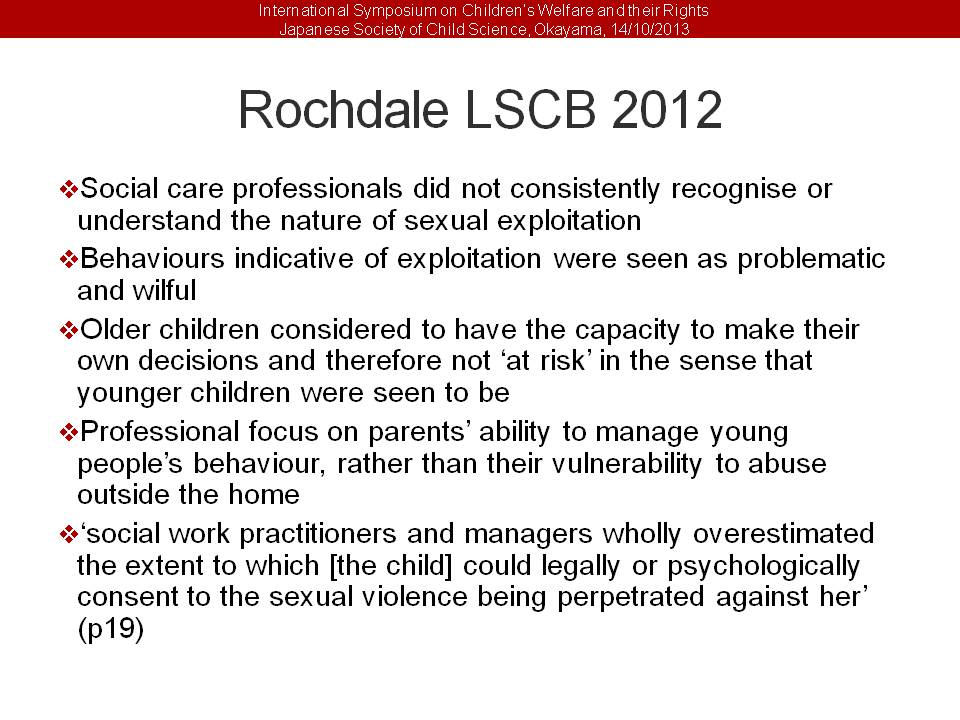

EnlargeHowever, the same study also found disturbingly high levels of contact sexual abuse to children by their peers. Coinciding with this research has been increased concern at gang-associated sexual violence perpetrated by children and young people on other children, including in the form of initiation ceremonies, drawing attention to a very small minority of so-called 'feral', highly disadvantaged young people who entirely lack a supporting family environment and rely on gang membership to gain a sense of belonging and of security. The Office of the Children's Commissioner has initiated a research project on gang-associated (peer:peer) sexual exploitation, which is ongoing. But in the last couple of years a number of child sexual exploitation scandals have rocked the UK. These have comprised 2 separate streams. The first concerned historical allegations of widespread abuse by celebrities who used their status to gain the trust of children, and whose activities appear to have been deliberately overlooked at the time as part of the culture of celebrity status and regarded as consensual. The second stream of scandals have concerned very vulnerable young people, including children who were in the care of the state, who were sexually exploited by groups of men over a period of years, during which the men first befriended the girls, dated them, and plied them with gifts and drugs before setting them to work as prostitutes. Many of the girls did not regard themselves as victims, and some refused to testify against them in court. Others reported their abuse to police and social services, but nothing was done to help them. The report of the local safeguarding children's board demonstrates the extent to which professionals appear to have been beguiled by the notion of the autonomous adolescent exercising free will in the choice of her own life path.

Enlarge

EnlargeThe safeguarding board concluded that social care professionals did not consistently recognise or understand the nature of sexual exploitation. Rather, behaviours that should have alerted them to the likelihood of exploitation were seen as problematic and wilful. Older children were considered to have the capacity to make their own decisions and therefore they were not regarded as being 'at risk' of abuse in the sense that younger children were. Professionals focused on parents' ability to manage the young people's behaviour, rather than on the girls' vulnerability to abuse outside the home. In relation to one young person, the board stated that 'social work practitioners and managers wholly overestimated the extent to which [the child] could legally or psychologically consent to the sexual violence being perpetrated against her' (p19).

Enlarge

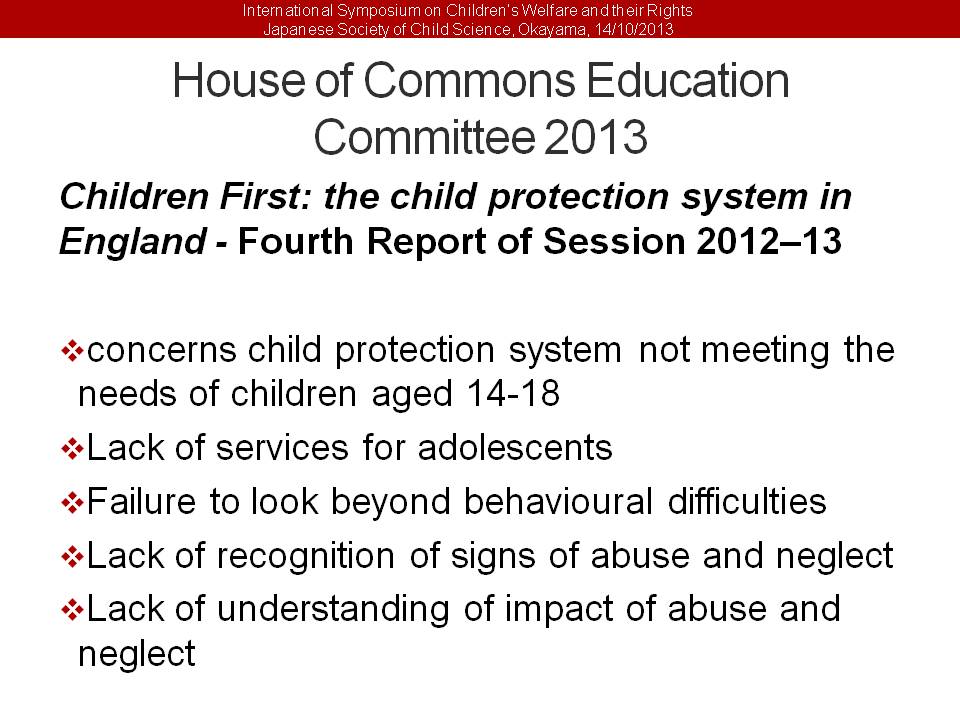

EnlargeThere have been other criticisms of the failure of the English child protection system in relation to adolescents, along similar lines. The House of Commons Education Committee, a cross-party parliamentary body, has expressed its concerns that the system is not meeting the needs of children aged 14-18 and attributes this to a lack of services for adolescents, a failure by professionals to look beyond the behavioural difficulties that vulnerable adolescents are only too liable to present; a lack of recognition of the signs of abuse and neglect; and a lack of understanding of the impact of abuse and neglect on older children. In short, adolescents are not afforded the same treatment as younger children because they are regarded as 'troublesome' rather than 'troubled' and their vulnerabilities are overlooked.

Enlarge

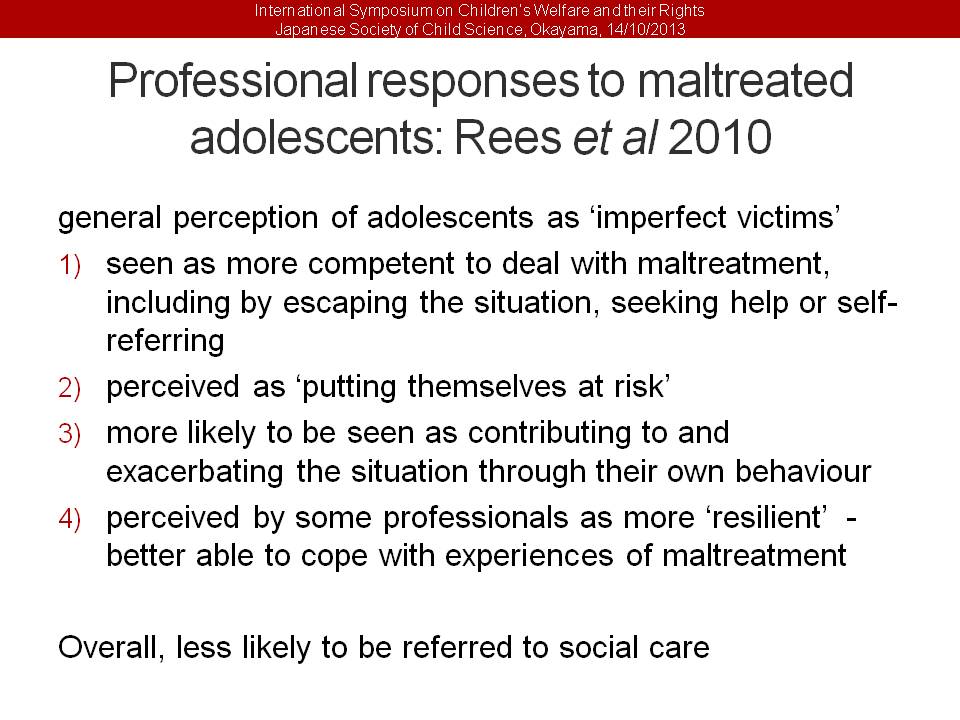

EnlargeThis state of affairs is eloquently summed up by Rees et al in their research on professional responses to maltreated adolescents, in which they describe a professional perception of adolescents as 'imperfect victims'. Adolescents in this study were regarded by professionals as more competent than younger children to respond to maltreatment, and were expected to be able to escape a situation of risk, to refer themselves to the authorities or actively to seek help in other ways. Consequently, those who failed to do so were regarded as exercising an autonomous choice and thereby 'putting themselves at risk'. Professionals were likely to blame young people in part for their predicament, as having either contributed to or exacerbated the situation through their own behaviour. They were also likely to be regarded as better able to cope with the experiences of maltreatment than younger children and to have greater resilience - notwithstanding the evidence base that sexual abuse is in many cases likely to result in greater harm to adolescents than to young children.

Enlarge

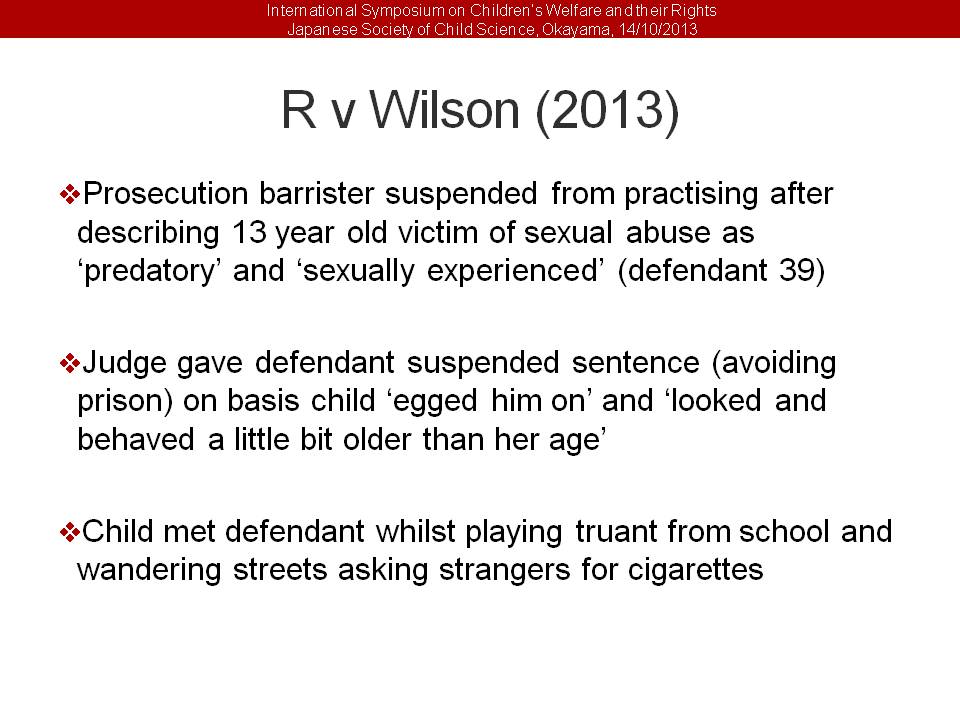

EnlargeOnly this summer Rees et al's conclusions were vividly confirmed by a case in court, in which the child victim, aged 13, had met the defendant, then aged 39, whilst playing truant from school and wandering the streets asking strangers for cigarettes. Child pornographic material was found on the defendant's computer when he was arrested. The prosecution barrister was suspended from practice - and has since had his licence to undertake sexual offence work but not disbarred from practice entirely - after he described the girl as 'predatory' and 'sexually experienced'. The judge in the case gave the defendant a suspended sentence, allowing him to avoid prison, on the basis that the child had 'egged him on' and 'looked and behaved a little bit older than her age'.

Enlarge

EnlargeBut of course, children are far from immune to adults' perceptions and expectations of them and this can contribute to the challenge in protecting them. In a report by the Child Exploitation and Online Protection Unit in 2011, attention was drawn to the problem of disclosure: 'victims frequently do not recognise that they are being exploited and do not disclose abuse'. This of course, was the case with the Rochdale girls and the victims of celebrity abusers too: adolescent sexual exploitation is often not recognised as such by its own victims, who have bought in to the prevailing culture of adolescents as autonomous agents. As a consequence, CEOP warn that agencies which do not proactively look for child sexual exploitation will fail to identify it and conclude that the majority of incidents of child sexual exploitation in the UK are unrecognised and unknown. The truth, however, is, as the report states, that 'although many victims can present as 'streetwise', they are in fact highly vulnerable'.

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

Enlarge

EnlargePerhaps we should be unsurprised, therefore, by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child's damning conclusions as to the 'general climate of intolerance and negative public attitudes towards children, especially adolescents' in the UK. The UNCRC report drew attention to evidence of this societal failure to acknowledge and respond to children's vulnerabilities, in the high rates of child substance misuse and bullying in the UK and high rates of teenage pregnancy in lower socio-economic groups. Doubtless in their next report in 2014-16, the Committee will add the recent and emerging scandals of child sexual exploitation to this list.

This destructive response to vulnerable adolescents extends to the youth justice system. In response to high profile cases of adolescent crime, the previous government not only refused to raise the age of criminal responsibility, but abolished the doctrine of doli incapax, under which a child aged 10-13 was regarded as incapable of forming the necessary criminal intent to be prosecuted, unless the contrary was shown by the prosecution. That government also sought to link children's rights with what it described as responsibilities, such that children are to be held responsible in law for their actions, notwithstanding their immaturity. So both the presumption that adolescents are making autonomous sexual choices and the treatment of adolescents by the youth justice system could be regarded as the adulteration of childhood, in the sense that children are being given freedom and responsibilities beyond their maturational capacities.

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies