Presented at the International Symposium on Children's Welfare and their Rights held by the Japanese Society of Child Science and

Child Research Net

Main Hall, Okayama Head Office of Benesse Corporation

October 14, 2013

The 'adulteration' of adolescence?: Balancing the rights of adolescents to autonomy and protection in the UK

As a socio-legal academic, the topic of children's welfare and their rights is central to my work, because in law these two concepts can appear to be contradictory: either children are vulnerable citizens in need of legal protection, or they have a claim to being rights-holders - but not both. In the West, the last 40 years has seen the rapid development of the children's rights movement, and the UNCRC has become the world's most successful - in the sense of most ratified - convention the world has ever seen. But it cannot be denied that Ellen Key's vision of the 20th century as the 'century of childhood' has not been realised. I was asked to present on the protection of children from a legal perspective, and I would like to use the opportunity to consider the way in which increasing recognition of adolescents as competent and capable of autonomy, coupled with societal changes in Western society over the course of the last century, have perhaps conspired to deny adequate protection to some older children. I will use the UK as a case study because this is an issue that has burst into the media spotlight in the last year or so there. I will address the argument that the underlying cause of the problem is 'too many rights' for children and suggest rather that a rights-based approach can provide the solution.

Historical Context

Enlarge

EnlargeAs in virtually every country in the world, the English child was historically the property of her father, who had complete control over her until she reached the age of 21. The family unit was seen as underpinning the fabric of society, and the father's authority as sacred. The state would only intervene in his domestic rule in extreme circumstances: in this case of Re Agar- Ellis a 16 year old child begged to be allowed to live with her mother as her father had sent her to board with a stranger, but the court refused to intervene in a matter of paternal rights. Until the 19th century, not only did mothers have no parental rights, but their legal identity was subsumed in or included under that of their husband.

Emancipation of Women

Enlarge

EnlargeThe emancipation of women led gradually to the erosion of paternal rights, but it also led to the introduction of the welfare principle in English law, which still governs court proceedings relating to the upbringing of children to this day: that is, that the welfare of the child is the court's 'paramount' (overriding) consideration. Somewhat ironically, the welfare principle appears to have been enacted in order to limit women's claims to parental rights by allowing judges to deem that the child's welfare was best served by upholding the father's 'sacred rights' over his children. But over time, the welfare principle came to favour mothers, as children were already the topic of philanthropic concern in the 19th century and became the subject of scientific and social enquiry in the 20th century. Claims as to the supposedly natural biological bond and recognition of the importance of high-quality emotional and physical care for children led to focus on the 'interests' of children and a shift in the balance of parental power between women and men. As divorce rates increased and adult conflict post-separation became an issue of increasing concern in relation to children's well-being, the concept of parental rights was redefined as parental responsibility in the 1989 Children Act.

Children's Liberationists

Enlarge

EnlargeMeanwhile, the children's liberation movement grew up in America in the 1960s and 70s, based on the argument that children, like women and blacks at the time, were an oppressed minority and the subject of exploitation by adults with power over them. The 'kiddy libbers' relied on the work such as that of the French social historian Philippe Ariès, who claimed in his book Centuries of Childhood that childhood as a life stage was not recognised before the 17th century and that children were treated as adults as soon as feasibly possible, a view that was highly influential for a while but has been significantly discredited today.

The kiddy libbers enjoyed some notable and important successes in America, including the famous case of In Re Gault in 1967, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Bill of Rights did not apply just to adults, and that children are entitled to the same procedural safeguards as those offered to adults by the US constitution, including the right to know the evidence against them, the right to legal representation and the right to appeal.

It isn't clear why the liberation movement did not take off to the same extent in the UK, although Jane Fortin suggests that many of the kiddy libbers claims - including rights for children to vote and to marry - ignored children's developmental immaturity to an extent which discredited the movement as a whole.

Advent of the Liberal Society

Enlarge

EnlargeNonetheless, with the rise of the liberal society in Western democracies, children were beginning to enjoy greater freedoms than ever before. John Locke, the 17th century English philosopher and physician is often credited as being the founder of the liberal philosophy. He challenged the divine right of kings to govern, and instead proposed that sovereignty resides in the people. He opposed authoritarianism at institutional and individual level and claimed equality of rights to life, liberty and property. He also advocated religious tolerance.

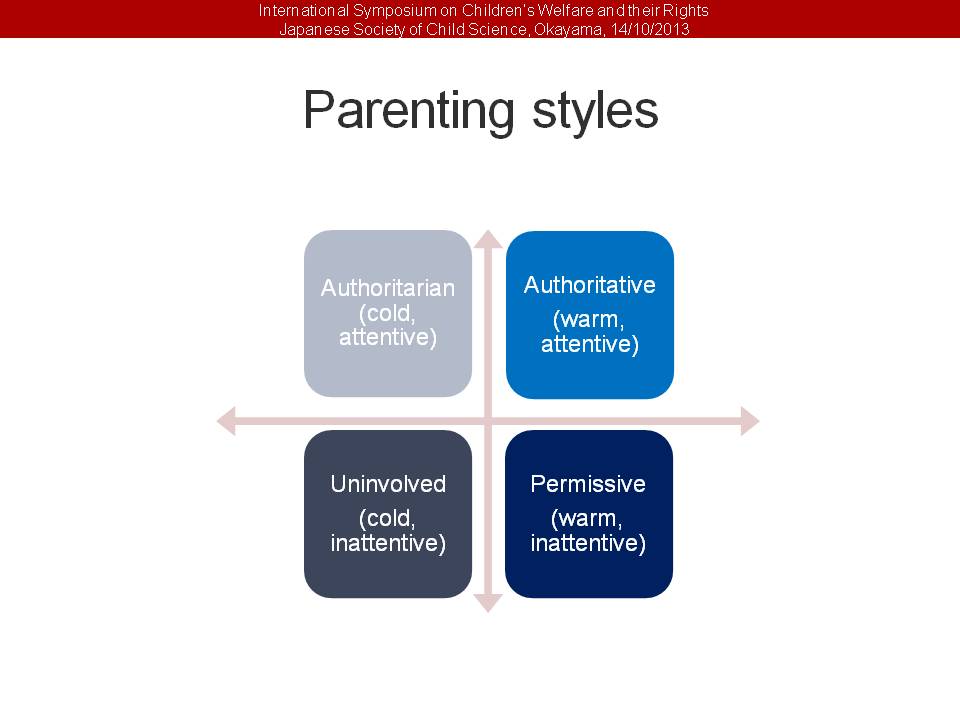

Fast forwarding a few centuries - and without suggesting that Locke would necessarily recognise or approve of all of the developments in so-called liberal societies of recent years - liberal democracies have witnessed in the last 100 years a massive shift from an authoritarian society with shared social mores to a culture of diversity and individualisation. Whilst children have experienced greater control over their physical freedom to play, parenting styles have become significantly less authoritarian and in many respects more permissive, children are exposed to a confusing array of values and cultures and the rise of the internet has allowed an alternative sense of online 'freedom' over which adults may have little control or indeed understanding.

Enlarge

EnlargeAt a simplistic level, there appears to have been a shift therefore from the top left box here to the bottom right.

Development of Children's Rights

Enlarge

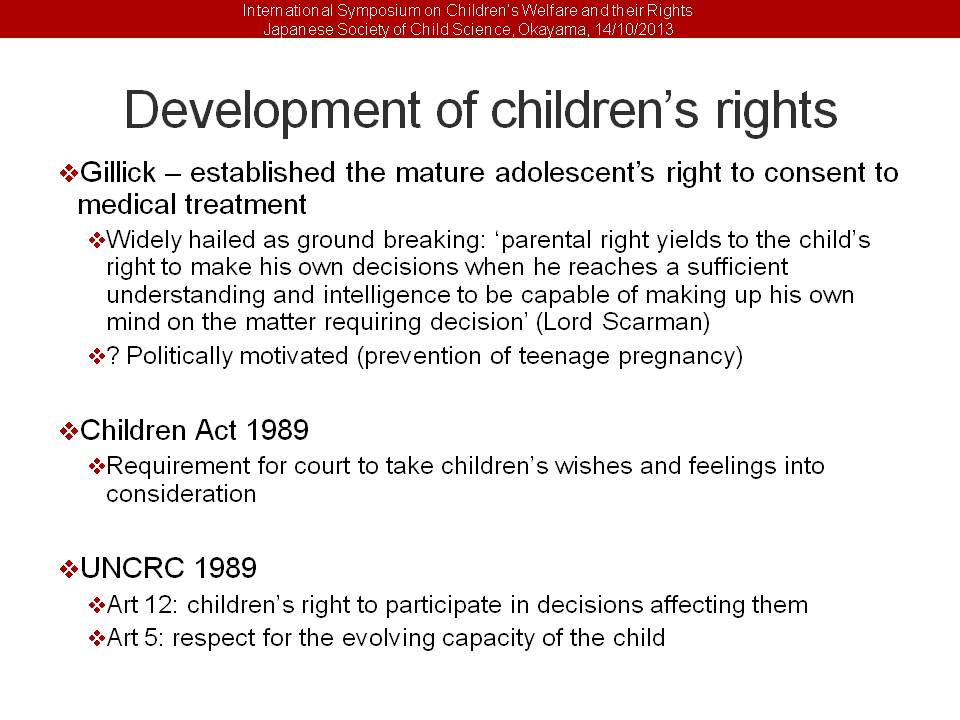

EnlargeAs the twin tracks of children's rights and a more permissive and liberal society came together, the 1980s saw a ground-breaking legal judgement in relation to adolescents' right to consent to medical treatment for themselves. Mrs Gillick objected to a circular to medical practitioners stating that they could prescribe contraceptives to teenagers without consulting their parents if the teenager refused to inform their parent and had sufficient understanding of the treatment to consent, claiming it was a breach of her parental rights. The words of Lord Scarman, that the 'parental right yields to the child's right to make his own decisions when he reaches a sufficient understanding and intelligence to be capable of making up his own mind on the matter requiring decision' led to widespread expectation that the judgement would allow adolescents greater autonomy over decisions affecting all areas of their lives, although this has not in fact come about and later judgements have limited the scope of the decision - in particular, so far, British courts have refused to allow adolescents the autonomy to decline medical treatment, although their counterparts in other parts of the world such as Canada have allowed children to choose to die.

Greater recognition of children's rights to express their views and participate in decision-making has, however, been reflected in the requirement that the court take into account children's wishes and feelings, in the light of their age and understanding in the Children Act 1989, closely aligned of course to article 12 of the UNCRC. Article 5 meanwhile, reflects the spirit of Gillick - the documents are almost cotemporaneous - in requiring that parents and others provide appropriate direction and guidance 'in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child': that is, children should be empowered to make decisions that they are competent to make for themselves.

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies