1. Current status of parents and children with "foreign backgrounds" in Japan

Currently, the number of children with foreign backgrounds is increasing in Japan. It is reported that over 150,000 children with foreign backgrounds attend Japanese elementary and junior high schools (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), 2022). In addition to these children at the compulsory education stage, the number of children at senior high school age with foreign backgrounds, as well as infants at preschool ages, is also significant. The term "children with foreign backgrounds" refers to children (and their parents) with various foreign nationalities living in Japan, including those with only Japanese nationality and those without any nationality.

Therefore, their native language and heritage language are diverse according to their backgrounds.*1

In order to receive compulsory education in the public system in Japan, all children are expected to receive education in Japanese. However, the level of Japanese proficiency varies among children with foreign backgrounds. Some need help to understand the language; some have good proficiency equivalent to their age. Likewise, their parents' Japanese skills also vary. Some have difficulty in using Japanese even for daily conversations, while some can efficiently use Japanese at their workplace.

Then, how does parents' ability to understand the language of their resident country affect children's language acquisition and future educational paths? How should Japanese schools and communities help these parents who could influence their children's language acquisition? Seeking answers to these questions, I have conducted a questionnaire survey targeting Brazilian families living in Japan, since their population size is remarkable among foreigners living in Japan. Questions items include the level of parents' and children's Japanese skills, and parents' expectations and concerns about children, including their future educational paths.

2. Impact of parents' Japanese skills on children's Japanese proficiency

The questionnaire survey was conducted in the autumn of 2020 in the form of an online survey using Google Forms (a web-based survey administration tool) considering the pandemic situation at that time. The survey participants were Brazilian parents living in Japan whose children (aged 4 to 12 years) attend Japanese kindergartens, daycare centers, ECEC centers, and elementary schools.

The language of the survey was Portuguese.*2 In response, I received answers from 41 participants. Regarding the respondents' academic background, 87.5 percent of the participants had high school certifications or above from Brazilian institutions. Therefore, the native language of most participants was Portuguese. The mean length of their stay in Japan was 13.58 years.

The level of parents' Japanese skills was measured using the scores obtained from the participants' answers regarding their difficulty in using Japanese. More precisely, the participants were asked eleven question items - eleven scenarios they are likely to encounter in their daily lives.*3 They answered regarding the degree of difficulty they might feel in using Japanese in each scenario. In contrast, the Japanese skills of children in early childhood and in elementary school (i.e., preschool-age children and school-age children) were measured based on their parents' observations of children's frequency and difficulty in using Japanese.

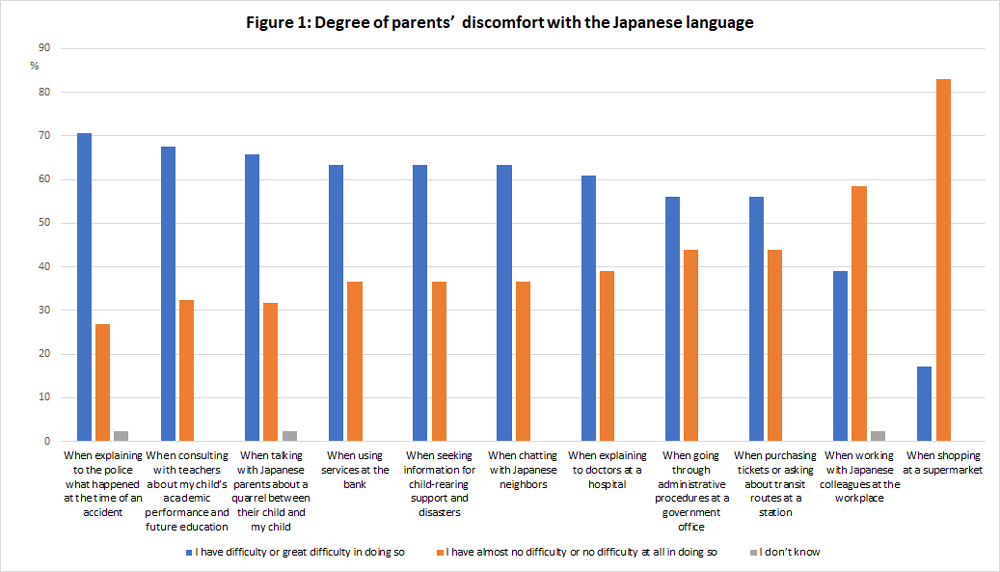

The analysis results show that the degree of parents' difficulty in using Japanese differs depending on each scenario. In particular, they feel the most difficulty "When explaining to the police what happened at the time of an accident," "When consulting with teachers about my child's academic performance and future education," and "When talking with Japanese parents about a quarrel between their child and my child." About 65% of the participants feel difficulty and need help in cases of accidents or troubles where they should properly understand and use the Japanese language.

Second, I conducted a Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relationship between parents' difficulty in using Japanese and the frequency of preschool-age children's use of the language. The impact of parents' Japanese skills on their children's use of Japanese varies, depending on each scenario. The analysis results show that the more difficulty parents feel in using Japanese, the less frequently their children use Japanese, for example, when playing with neighborhood friends (r=.36, p<.05). These parents have difficulty using the language even "when shopping at a supermarket" where complicated conversations do not usually take place.

Third, I examined the relationship between parents' difficulty and school-age children's difficulty in using Japanese. A stronger correlation was confirmed in overall scenarios compared to the above results (regarding parents and preschool-age children). On the occasion of "When shopping at a supermarket," in particular, the more difficulty parents feel in using Japanese, the more their children have difficulty in using Japanese, for example, when talking with teachers, chatting and playing with friends at school (r=.54, p<.01), taking lessons at school (r=.38, p<.05), and doing assignments at home (r=.54, p<.01).

To sum up, there is a significant association between the Japanese skills of parents and that of both preschool and school-age children. This trend is also confirmed as more potent between parents and school-age children. In addition, if parents' Japanese skills are poor, they cannot acquire sufficient information necessary for living and education and convey such information to their children.

Therefore, preschool facilities (e.g., daycare centers) and schools should provide special attention and support for children whose parents have poor Japanese skills.

3. Relationship between children's Japanese skills in early childhood and elementary school age

As explained above, there is an association between the Japanese skills of parents and that of their children. Next, I will discuss it from the viewpoint of children's developmental status. First, I examined the relationship between the frequency of using Japanese by preschool-age children and the difficulty in using Japanese felt by school-age children. As a result, a significant correlation was confirmed between preschool-age children's Japanese use and school-age children's difficulty with Japanese in all scenarios except "When using Japanese with siblings." In particular, the less frequently preschool-age children use Japanese when talking with friends (r=.61, p<.01) and teachers (r=.64, p<.01) at preschool facilities, the more difficulty they feel when quarreling with Japanese friends using Japanese at elementary school age. Therefore, the frequency of using Japanese during early childhood may later affect their ability to achieve smooth communication with their peers. In addition, it is confirmed that the less frequently preschool-age children use Japanese when talking with friends (r=.52, p<.01) and teachers (r=.49, p<.01) at preschool facilities, the more difficulty they feel when receiving education in Japanese at elementary schools.

The above results suggest that it is necessary to provide JSL support for not only school-age children but also children in their early childhood stage. If parents' Japanese skills are poor, children are most likely to hear and use their parents' native language at home. This situation is preferable for children in the context of native language acquisition, but at the same time, disadvantageous to their acquisition of the Japanese language due to fewer opportunities to interact with Japanese. Therefore, preschool facilities should provide quality JSL education for children with foreign backgrounds, including activities where children can actively use the Japanese language and closely interact with Japanese ECEC teachers. It should be noted, however, that preschool-age children require particular approaches according to their developmental stages, which might differ from the JSL education provided for school-age children. For more information about such approaches, please refer to another study (Tomo, 2023).

4. Parents' Japanese skills and expectations toward children's future educational paths

One of the education barriers facing children with foreign backgrounds is the requirement of attending Japanese high schools. The percentage of children going to senior high school is 98.9% in Japan (MEXT, 2022), indicating the importance of obtaining a high school qualification for future careers. However, a large number of children with foreign backgrounds give up or stop attending high school due to their poor Japanese skills. The results of this survey show a significant positive correlation between parents' Japanese skills and their expectations of children to earn a high school qualification.

In particular, if parents have difficulty using the Japanese language when dealing with accidents and troublesome situations, such as "When talking with Japanese parents about a quarrel between their child and my child" (r=.41, p<.05) and "When explaining to the police what happened at the time of an accident" (r=.36, p<.05), or when seeking information necessary for living or having communications at the workplace, such as "When using services at the bank" (r=.35, p<.05), "When seeking information for child-rearing support and disasters" (r=.33, p<.05), and "When working with Japanese colleagues at the workplace" (r=.43, p<.01), they are more likely to not recommend children to go to Japanese high schools.

The length of stay for children with foreign backgrounds tends to be longer than before due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Under such circumstances, children can complete the compulsory education stage without acquiring adequate Japanese skills. In addition, the acquisition of Portuguese, their native or heritage language, is inadequate for their age. Therefore, it would be difficult for them to receive secondary and higher education in future. Suppose parents' Japanese skills affect their children's future educational paths. In that case, providing parents with accurate information about JSL support for adults and children's Japanese proficiency status is essential. In many cases, parents with poor Japanese skills can neither understand the importance of high school qualifications in Japan nor accurately recognize the level of their children's Japanese skills. Therefore, schools should, through collaboration with education committees and other educational institutions, not only support children's JSL skills but also provide information to their parents about Japan's higher education system and children's daily learning conditions.

5. Parents' Japanese skills and concerns about their children

Next, I will explain the relationship between parents' Japanese skills and their concerns for their children. I analyzed the participants' answers regarding concerns over children's "relationships with friends," "academic performance and Japanese skills," and "developmental delays." I examined how parents' difficulty in using Japanese relates to these concerns. As a result, it is confirmed that the more difficulty parents feel in using Japanese, the more seriously concerned they are about their children's troubles with friends. In particular, if parents cannot adequately talk with Japanese teachers about their children's future educational paths and academic performance (r=-.42, p<.01) or cannot obtain sufficient information necessary for child-rearing support and disaster events (r=-.45, p<.01), they are more concerned about children's troubles with friends. The same tendency was observed regarding children's academic performance, Japanese skills, and developmental delays.

For parents who have difficulty in using Japanese when chatting with Japanese neighbors, they are more concerned about children's troubles with friends (r=-.33, p<.05), academic performance at school (r=-.32, p<.05), Japanese conversations (r=.49, p<.01), Japanese reading and writing (r=-.35, p<.05), and developmental delays (r=-.34, p<.05).

In conclusion, parents who have difficulty using the Japanese language are likely to be more concerned about their children. Therefore, it is essential to not only support children but also to provide their parents with opportunities to consult about children's developmental status in their native language. In addition, children's troubles with friends often occur due to different cultural habits. For example, when Japanese people wish to borrow a pencil from a friend, it is customary to ask, "Can I borrow your pencil?" first. However, in some cultures people do not feel the need to ask when borrowing a pencil from a close friend (Saito et al., 2011). In this context, explaining such cultural diversities in customs and ways of thinking to parents is also an important way of providing support.

6. Community support for foreign parents

The Japanese government has been working steadily to establish a legal framework for the childcare and education of children with foreign backgrounds. This effort has become more remarkable since 1990 when the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act was revised. In response to this revision, there was an increase in the number of children with foreign backgrounds, and a new system of "Students Achieving the Proficiency Level of Lower Secondary School" was introduced. In 2013, MEXT requested educational institutions to establish a comprehensive guidance and support system for foreign children/students, ranging from acceptance of children from overseas to consultation regarding career paths after school graduation. In 2014, the Ordinance for Enforcement of the School Education Act was partially revised. A "special education program" was introduced to provide JSL education for foreign children/students. Since then, the JSL education curriculum has been shaped through the accumulation of trial and error experiences.

Furthermore, the Childcare Guidelines for Daycare Centers were revised in 2017 (enacted in 2018). The guidelines explicitly specify that "Daycare centers shall endeavor to provide individual assistance for families requiring special consideration (i.e., foreign families) according to their situations." Thus, a special support system was established for young children and families with foreign backgrounds. At the same time, the Course of Study for Kindergartens and the Course of Study and Guideline of Day Care for Integrated Centre for Early Childhood Education and Care were revised. Under the section "Instructions for young children requiring special considerations", a new statement of "Special considerations shall be provided for infants and young children from overseas with difficulty in acquiring the Japanese language, assisting them in adapting themselves to kindergarten life" was inserted.*4 More specifically, the statement explains that "Kindergartens and ECEC centers shall carefully prepare teaching content and methods organizationally and systematically considering the actual status of infants and young children from overseas who have difficulty in acquiring the competence in Japanese language necessary to live in Japan, thereby assisting them to feel safe and fulfill their potential."

However, these revisions have yet to be thoroughly put into practice in schools and childcare facilities. For example, less than 10 % of municipal governments answered they had taken some measures for childcare facilities in response to these revisions (Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting, 2021). There are numerous areas where support for foreign parents still needs to be improved. Of course, this slow progress is partly due to foreign parents' busy working lives and shortage of time available to receive the necessary support. In addition, there may be companies employing foreign people that would not consider JSL support for them.

On the other hand, some private sector services provide counseling for foreign parents, including support for children with possible developmental disorders. In addition, concerning governmental groups, for example, the municipal government in Ogaki City, Gifu Prefecture, provides guidance for foreign parents with preschool-age children (Uchida, 2022). There are also some areas where social interactions are facilitated among residents of UR housing (Murasawa, 2022). In the future, these types of support for foreign parents will become more requisite, including support of various institutions such as communities, municipalities, and the private sector.

Like children with Japanese nationality whose native language is Japanese, children with foreign backgrounds also inherit the future of Japan. Therefore, the Japanese government should establish an effective educational support system under its legal framework. Furthermore, community support for foreign parents as citizens is also essential for revitalizing communities. In the future, Japanese society will become increasingly multinational, to a greater extent than ever. Therefore, we should accept foreign families as citizens in our communities, work together on community activities regardless of nationalities, and build a trusting relationship by supporting foreign parents in their child-rearing. Considering the results of this survey confirming the impact of parents' language skills on children's development, support for foreign parents, including child-rearing and educational support for their children, is indispensable for the future of Japan.

In this report, I discussed the analysis results obtained from a survey on Brazilian families living in Japan. It is confirmed that children's acquisition and use of the Japanese language in early childhood will affect their use of the language in their later life. In addition, parents' Japanese skills also affect their children's use of the language. It should be noted that these findings can be applied to any children with foreign backgrounds. Therefore, we should understand such influence factors when providing support for children and parents with foreign backgrounds, including their child-rearing, education, and the parents themselves.

References:

- Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting Co., Ltd. (2021). "FY2020 Research Project to Promote Support for Children and Child-Raising: A Survey Report on the Education and Childcare of Children with Foreign Backgrounds"

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. (2022). "FY2022 School Basic Survey (primary and secondary education institutions, specialized training colleges, and miscellaneous schools)"

https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00400001&tstat=000001011528&cycle=0&tclass1=000001172319&tclass2=000001172320&tclass3=000001172415&tclass4=000001172416&tclass5val=0 (in Japanese, Last viewed: February 28, 2023) - Kazuko Nakajima. (2005). Heritage Language Education in Canada: Looking Forward in Heritage Languages: The Development and Denial of Canada's Linguistic Resources (authored by Jim Cummins & Marcel Danesi; translated by Kazuko Nakajima and Toshiyuki Takagaki). 155-180. Akashi-Shoten.

- Yoshiaki Murasawa. (2022). Possibility of Non-formal Education Communities for Foreign Children: Support for Japanese Language Classes through Collaboration between University and Companies in Educational Support for Foreign Children (authored and edited by Hiromi Saito). Kaneko-Shobo.

- Hiromi Saito. (2011) Support Guidebook for Foreign Schoolchildren: Considering Children's Life Courses. BONJINSHA Inc.

- Rieko Tomo. (2022). Developmental Support for Infants and Toddlers with Foreign Backgrounds in Children's Development 172: Rediscover Children's Language! 82-87.

- Rieko Tomo & Pleiades Tiharu Inaoka. (2023). Current Status and Support for the Use of Japanese Language by Children with Brazilian Backgrounds: Focusing on Children in Infancy and Childhood. Journal of Contemporary Social Studies, vol. 19, pp. 1-18.

- Chiharu Uchida. (2022). Preschools for Preschool Children: Initiatives of Ogaki City in Educational Support for Foreign Children (authored and edited by Hiromi Saito). Kaneko-Shobo.

Notes:

- *1 The term "Heritage Language" means a language inherited from parents (Nakajima, 2005).

- *2 The questionnaire survey was translated from the Japanese language to the Portuguese language before starting the survey. I would like to thank Dr. Pleiades Tiharu Inaoka (Kanazawa University), who helped me to review the questions.

- *3 I have listed the following eleven scenarios that foreign people might experience in their daily lives in Japan:

- When shopping at a supermarket

- When chatting with Japanese neighbors

- When consulting with teachers about children's academic performance and future education

- When talking with Japanese parents about a quarrel between their child and my child

- When working with Japanese colleagues at the workplace

- When explaining the condition of myself and my child to doctors at a hospital

- When going through administrative procedures at a government office

- When using services at the bank

- When explaining to the police what happened at the time of an accident

- When purchasing tickets or asking about transit routes at a station

- When seeking information for child-rearing support, life, disaster etc. in Japan

- *4 The Guidelines for Education and Childcare Integrated ECEC Centers use "kindergarten children" instead of "infants" in overall texts.