Presented at the International Symposium on Children's Welfare and their Rights held by the Japanese Society of Child Science and

Child Research Net

Main Hall, Okayama Head Office of Benesse Corporation

October 14, 2013

The 'adulteration' of adolescence?: Balancing the rights of adolescents to autonomy and protection in the UK

Enlarge

EnlargeIt is tempting, given the history that I have outlined, to lay this at the door of children's rights and to conclude that the 21st century Western child suffers from too many rights and too little care, and that in the case of adolescents, the children's rights agenda has served only to exacerbate the vulnerability of the objects of its concern.

Goldstein, Freud and Solnit have long argued that the only right that children have is the right to autonomous parents, based on the simple idea that parental rights are the best means by which to promote the welfare of children. In the US, Martin Guggenheim continues vociferously to oppose the notion of children as rights holders, maintaining that it 'has been a source of great danger and little good' and that it 'tends to ignore basic truths and problems'. He advocates a return to the days of parental rights, when 'the important decisions affecting children are made for them by those who know and love them best'. Children, he says, do not need rights within the family.

Enlarge

EnlargeHis is an alluring proposition, particularly in the light of the finding by CEOP, that the UK is a popular online 'destination' for foreign perpetrators, because the free and liberal nature of society offers greater opportunities for abusers. There are 2 issues here, children's rights within and outside the family. The fallacy in Guggenheim's argument in relation to rights within the family is immediately apparent to all those working in the child protection system, who have long-since realised that the vast majority of maltreatment perpetrated on children is committed by those who are entrusted with their care. Children do, then, need rights to protection within - and even against - their own family. Outside the family, parents can't protect their children against the abuses of the state, as graphically illustrated by the case of In Re Gault - so children need protection rights outside the family as well. But what about children's rights to express their views under articles 12 and 13, and the principle underlying article 5, namely that children should be allowed to make decisions for themselves when they are competent to do so? Are these so-called 'autonomy' rights perhaps 'source of great danger and little good', as Martin Guggenheim would have us believe? I'd like to conclude by arguing that fulfilment of children's rights under the UNCRC, if interpreted sensitively, can in fact serve to promote rather than undermine young people's protection.

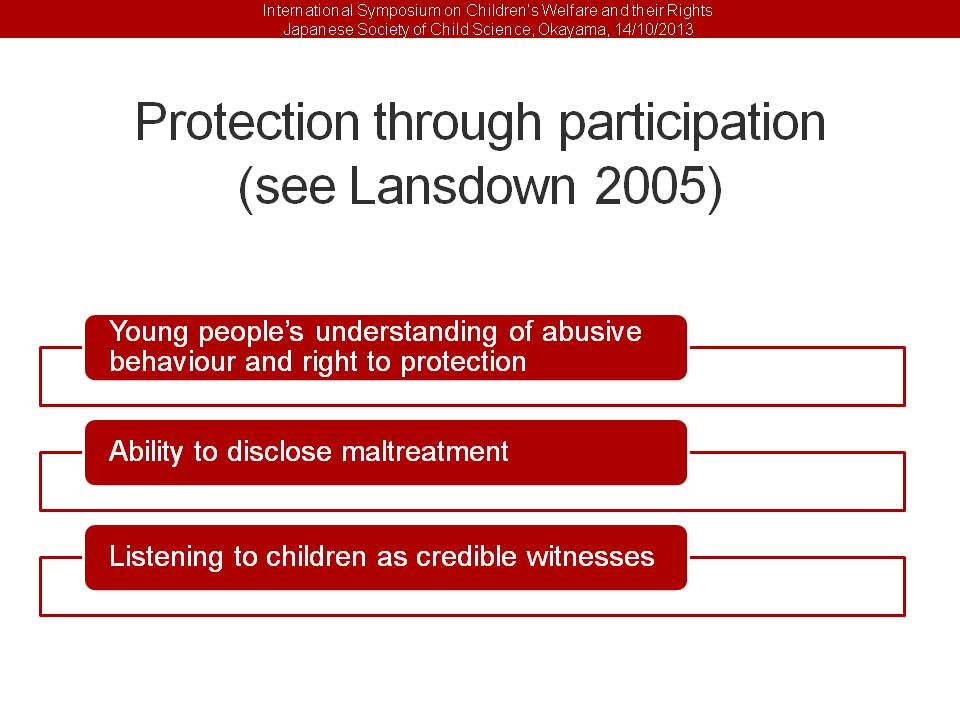

Enlarge

EnlargeLansdown, who authored the Innocenti UNICEF report on article 5 and who contributes to the teaching on the Child Studies programme that I run at King's, has argued persuasively that children's protection rights cannot be realised through a welfare approach that relies on adults to promote and protect children's best interests. The worldwide scandal of child abuse perpetrated by institutions belonging to the Catholic church highlights all of the three points on the slide here. Firstly, it is of fundamental importance that children understand what constitutes appropriate adult behaviour towards them and that they have a right to be protected from maltreatment. Secondly, children need the skills and confidence to be able to communicate and disclose abuse to an adult with whom they have a relationship of trust. Thirdly, adults need to respect children's evidence as credible and act accordingly. All these attributes require respect for the views of the child, in accordance with article 12 of the UNCRC. A number of cases of institutional abuse of children in the UK have resulted in greater respect for children's participation rights under article 12 being embedded in legislation and guidance, to ensure that professionals consult children as to their wishes and feelings and that children are able to challenge what is happening to them. A professional culture of preferring the account of the adults responsible for children's welfare has given way to a presumption that children should be believed in the first instance and their allegations taken seriously - although my own experience of research with looked after young people suggests that this is still not the case for many. Finally, realisation of children's article 12 rights to participate in matters affecting them provides children with the opportunity to develop the capabilities that are prerequisite to autonomous decision-making.

Enlarge

EnlargeArmed with such capacities, article 5 implies that as children acquire competence to act autonomously, responsibility for the exercise of their rights is transferred from parent to child. Article 5 enables children to make decisions for themselves to the extent to which they are competent to do so, and thereby promotes the abilities of children to take on additional responsibility as they become older and to acquire confidence and judgement in autonomous decision-making. However article 5 does not provide young people with the right to do as they please, nor does it provide professionals with an excuse to fail to intervene to protect them on the basis that they are exercising their right to autonomy. On the contrary, it must be balanced by article 3, which stipulates that the child's best interests shall be a primary consideration in all matters affecting them.

Conclusion

Enlarge

EnlargeSo what are the implications for child protection and welfare of this approach? Firstly, the implication of article 5 is that greater account needs to be taken of children's individual maturational stage. This means a refocus on developmental perspectives of childhood, including an appreciation that children's maturity will be affected by a range of factors, including their experiences and opportunities to date, not least the extent to which they have been enabled to exercise their article 12 participation rights. In relation to the very troubled adolescents that have been the subject of this presentation, it means recognition that notwithstanding their behavior, it is likely that they are significantly developmentally less mature than their peers. The work of Eileen Vizard and others in this area has demonstrated this to be the case in particular in relation to young offenders, making nonsense of the political rhetoric that insists on holding young children to account for their actions. But I suggest that it also means greater attention to the legal construct of childhood, the fundamental purpose of which in every society is to provide appropriate protection for its youngest members - from their own mistakes as much as those of adults.

Enlarge

EnlargeFinally, what does respect for the legal status of childhood as protected citizens imply? Firstly, it means a need to change societal attitudes to adolescents, recognizing that however different they may be from younger children, there are nonetheless good developmental reasons for not according them the adult status they may crave, but instead acknowledging that their best interests remain a primary concern. It means that adolescent 'autonomy' rights are not an excuse for professionals to fail to engage with 'difficult' teenagers and that cultural differences in acceptable presentation and conduct are not an invitation to abuse. The rising tide of peer to peer abuse needs to be tackled urgently, but the approach must prioritise the status of both parties as children rather than rushing to criminalise a young perpetrator.

We also need to renegotiate the relationship between the state and family, endeavouring to overcome our natural resistance to state interference in family life in recognition of the changing nature of family and community support and in accordance with member states' duties under the UNCRC. There is evidence of an erosion of confidence amongst parents who may feel disempowered both by their struggle to deal with 'difficult' or disaffected adolescents and by professionals who appear quick to criticize. Enhanced support for families should include a more sympathetic response to the pressures of modern parenthood, early intervention for 'difficult' adolescents, and the promotion of authoritative parenting styles. Authoritative parenting is described as parenting which allows children to express their opinions and to develop independence but is warm and nurturing and places limits, consequences and expectations on children's behavior: in other words, it respects children's article 12 and article 5 rights but without losing sight of the central importance of article 3, the child's best interests. The rights of adolescents do not need to be won at cost to their welfare.

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies

Jenny Driscoll, Lecturer in Child Studies