We wonder whether young children feel excitement and pleasure while they are playing in the schoolyard. We wonder whether we, adults, really understand their play. How do they start, develop and end their play? What factors would trigger their excitement and pleasure? To find the answer, the ambient environment of young children were examined whilst engaged in play.

Several studies have revealed the factors of schoolyards that increase children's excitement and enjoyment (Senda, 2016 & 2018). For example, Canadian researchers Herrington and Lesmeister suggested there were key criteria, called Seven Cs, to design an attractive schoolyard with outdoor play spaces and equipment (Herrington & Lesmeister, 2006). The Seven Cs include character, context, connectivity, change, chance, clarity, and challenge.

More precisely, the role of "character" means the characteristics and appearance of play spaces; "context," space density and presence of adults and the connectivity factor; "connection," different elements and pathways; "change," places to play alone, continuous changes, and liquidity; "chance," flexibility, selectivity, and versatility; "clarity," physical legibility; and "challenge," several levels of difficulty and graduated challenges for each activity.

Other researchers also reported critical factors. For example, some insisted on the importance of open areas with differing ground surfaces that attract physical activity levels (Cosco, Moore, & Islam,2010). Others discussed different playground designs and equipment configurations, which had an effect on children's satisfaction and concentration (Dyment & O'Connel, 2013; Sporrel, Caljouw, & Withagen, 2017). Furthermore, the number of children and their play type may change depending on the amount and type of movable play materials in the playground (Jarrett, French-Lee, Bulunuz, & Bulunuz, 2011).

So then, in what context does children's play start and develop in the actual play scene?

1. Process of Play

To find an answer to this question, a research study was conducted observing children's play with the support of Kawawa Nursery School located in Yokohama City, Kanagawa Prefecture (Sumiya, 2019). This daycare center practices early childhood education through children's play in the schoolyard (Terada, 2010; Terada & Miyahara, 2014; Aoki & Kawabe, 2015).

A video was recorded of children playing at various locations in the schoolyard, including the sloping sandpit (called "Daimore"). Since we successfully recorded children in the sloping sandpit for more than 10 minutes, we chose these activities for our study. We classified these activities into five cases and analyzed the play process in each case More precisely, we first classified their actions into three categories of "Actions with Water," "Actions with Sand," and "Movements" on the "upper part" and the "lower part" of the sloping sandpit, and recorded the flow of their activities.

Table 1: Five Play Patterns

(1) The role of unexpected events in the process of play

One of our discoveries in the course of this study is the importance of unexpected events in the process of play. Children's activities were recorded at each stage of "Beginning of Play," "Germination of Play Development," "Play Development," and "End of Play." As mentioned above, five cases were observed. Four out of the five cases show children's enthusiasm and engagement. Such enthusiasm was triggered by unexpected events for children in each case, such as water overflowing from a stream, or a small puddle created by them (as a pond/dam). Each time, children had a new idea and developed their play further.

For example, in Case 3, Child A and Child B tried to create a water channel from a stream of water on one side of the sandpit through to the other side, and then hold back the water in a hole in the ground to create a small puddle. Naturally, the hole was gradually filled with water, and overflow occurred. First, children tried to stop overflow in one area by piling up sand. Then, water overflowed in another area and gushed out of the sandpit. When children noticed the overflow, they attempted to stop it by taking out the bamboo tubes from the water channel and holding back the stream of water, screaming, "Wooh!" "Oh, no!" or "Stop it!" This indicates that unexpected events can trigger children's excitement more effectively than planned situations.

Children excited at the sight of water overflowing from the puddle

Children excited at the sight of water overflowing from the puddle(2) The role of water in children's activities in the sandpit

Another discovery was the importance of water in children's activities in the sloping sandpit. Four out of the five patterns used water from a stream of water running around the sloping sandpit. In the remaining pattern alone, children did not use water in their play and did not show much enthusiasm. The previous study also indicates that play activities lasted longer when children used water in the sandpit (Herrington & Leseister, 2006). In that study, however, they did not clarify the role of water. Our research revealed that water functioned as a tool to search and identify locations for children and connect them playing in different locations.

In the three cases, children in the sloping sandpit immediately started pouring water into the stream. They did not have a discussion or plan something together before using water. It seems that they tried to check the condition of the sandpit by observing the flow of water. Their play seemed to develop as they followed the water movement and created a puddle by digging deeper so that water filled up the hole, or altered the stream of water into a water channel.

Another role of water is to connect children playing in different locations. For example, in the case of the sandpit we observed, small groups of children were playing with sand in the upper and lower parts and the left and right parts of the sandpit. In the case of Case 2, at first two groups of children were trying to create a stream of water in the upper and lower parts. Then, suddenly, water from the upper part flowed into the stream of water in the lower part. As a result, the two groups cooperated to create a stream of water flowing from the upper to the lower part. In the end, they had built a dam in between the two water passages, then created a connecting water channel using bamboo tubes, eventually constructing a large single water flow (this activity ended before full completion).

(3) Ecological map

In general, recording a location (mapping) relies on objective measurements (e.g., length, distance, and area). However, an American psychologist Heft discussed that children's understanding of location in outdoor activities might change according to their affordances of the environment (Heft, 1988). Affordance in this context means "what they can do there." For example, children can describe the location using affordances such as "climb-on-able," "run-able," and "sit-on-able."

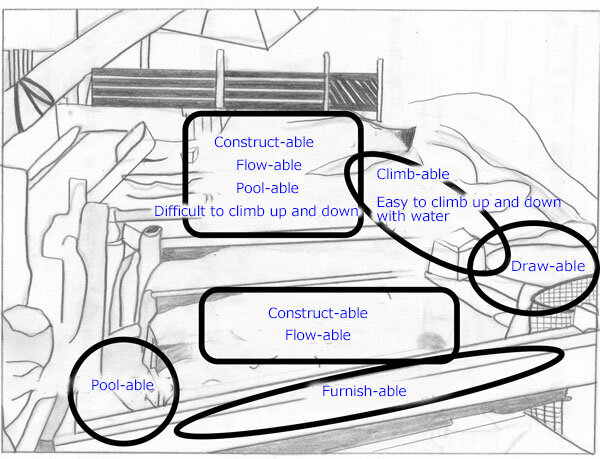

As such, "what they can do there" represents functional significance that individuals obtain from the environment. Figure 1 shows the sloping sandpit map based on functional significance (hereinafter, the "ecological map"). Functional significance may vary depending on each child's physical and mental developmental stage, regardless of the play location. For example, bringing a bucketful of water to the upper part of the sloping sandpit may be difficult for a three-year-old child, even if there are stone steps.

The ecological map in Figure 1 was made based on our observation of four- and five-year-olds. To create an ecological map, it is necessary to observe children's activities and record their actual behavior patterns. Children's activities we observed include "flowing water," "pooling water," and "creating a hole in the ground or a stream of water." They "carried a bucket of water up and down" the slope sandpit using the stone steps and "placed play equipment" on the storage space.

An ecological map reflects the significance of a location to the users. Creating ecological maps for a location that generates children's excitement and pleasure can help us identify functional significance and layouts specific to such a location. In this way, we can design an effective schoolyard based on more explicit evidence.

2. Designing of Play and Locations; Adults' Understanding and Efforts

The sloping sandpit is usually called "Daimore," originating from the word meaning a massive water flow from flooding (Terada & Miyahara, 2014; Okuda & Sumiya, 2018). This name indicates that the sandpit was designed to generate unexpected events on a smaller scale such as "water overflowing." The sandpit design contains various ideas, and the essential idea is the slope part of the sandpit. Unlike a miniature hill, this slope was created based on a terraced foundation, spreading mountain sand over it. This structure ensures children's postural stabilization while they are playing. In addition, the slope on the lower part is steeper, while the slope on the upper part is less so. Therefore, children feel comfortable when they climb up to the top of the sandpit. There are stone steps placed at intervals tailored to children's stride length alongside the slope. This enables children to carry a bucket of water easily. As you can see, even the slope design alone contains various creative ideas.

Children playing with plenty of buckets

Children playing with plenty of bucketsPlay activities with plenty of equipment available (instead of minimally given) can inspire children's imaginative ideas.

Play equipment is also a critical tool to generate children's excitement and pleasure. In the case of the sloping sandpit, there is plenty of play equipment, including about 30 buckets, ten watering cans, and 20 small and large bamboo tubes. These are provided for children to create a stream of water, etc. The size of the bucket is suitable for young children to carry water. Children chose these tools according to the condition of the sandpit. For example, they used a bamboo tube to create a stream of water. To spread a large amount of water from the upper sandpit, they chose buckets and watering cans. Because children are given plenty of equipment, they can endlessly invent creative ideas in their play.

Children use a bucket not only to carry water but also to carry sand and hold back a stream of water. Plenty of equipment stored by the sandpit: buckets, watering cans, bamboo tubes, wood chips, etc.

Director Terada at Kawawa Nursery School conveys the importance of "turning coincidence into necessity" (Terada, 2010). There are numerous unexpected events in the schoolyard. Are they mere unexpected events of coincidence or a chance to discover new interests and ideas? Children's affordance will alter if adults have such perspectives in mind.

In early childhood education facilities, environmental factors, which include physical and human, are specified as variables affecting the quality of children's play. Physical environmental factors include the ground surface conditions, the playground design (type and number of play equipment, number of plants, percentage of asphalt pavement surfaces, etc.), the layout of fixed equipment, and the variety and number of tools. Human environmental factors include the playground's rules, childcare workers' involvement and perspectives, children's physical abilities, their family's economic situation, and so on. Some researchers reported that childcare workers' attitudes and practices towards children's play are one of the most influential human factors (Pate, Pfeiffer, Trost, Ziegler, & Dowda, 2004). The sloping sandpit we introduced in this article was designed by adults who wished to create a place where various unexpected events and choices are likely to occur, and children can think and play on their own when encountering such events. It is also noteworthy that children may have learned how to capture the challenge of unexpected events from such adults. In the end, the most critical factor in designing a schoolyard that provides children's excitement and pleasure is adults who understand the value of play and strive to create an effective environment for children.

References

- Hisako Aoki & Takako Kawabe (2015). Youji kyouiku chi no tankyu8 Asobi no fookuroa [Early Childhood Research: Intellectual Quest 8 Folklore of Play]., Houbunshorin, Tokyo.

- Barbour, A. (1999). The impact of playground design on the play behaviors of children with differing levels of physical competence. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 14(1), 75-98.

- Cosco, N., Moore, R., & Islam, M. (2010). Behavioral mapping: A method for linking preschool physical activity and outdoor design. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42(3): 513-519.

- Dyment, J & O'Connell, T. (2013). The impact of playground design on play choices and behaviors of pre-school children. Children's Geographies, 11(3), 263-280.

- Heft, H. (1988). Affordances of children's environments: A functional approach to environmental description. Children's Environments Quarterly, 5(3), 29-37.

- Herrington, S. & Lesmeister, C. (2006). The design of landscapes at child-care centres: Seven Cs. Landscape Research, 31(1),63-82.

- Jarrett, O., French-Lee, S., Bulunuz, N., & Bulunuz, M. (2011). Play in the Sandpit: A University and a Child-Care Center Collaborate in Facilitated-Action Research. American Journal of play, 3(2), 221-237.

- Kytta, M. (2004). The extent of children's independent mobility and the number of actualized affordances as criteria for child-friendly environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(2), 179-198.

- Enji Okuda & Masashi Sumiya. (2018). Asobino fukken [Reinstatement of Play]. Omi Academic Publishing, Shiga.

- Pate, R., Pfeiffer, K., Trost, S., Ziegler, P., & Dowda, M. (2004). Physical activity among children attending preschools. Pediatrics, 114(5), 1258-1263.

- Mitsuru Senda. (2016). Children's Garden. Kodomo no niwa Senda Mitsuru+kankyo dezainkenkyujo no "entei ensha 30" [Kindergarten Yards & Buildings 30 by Mitsuru Senda & Environment Design Institute]. Sekaibunkasha, Tokyo.

- Mitsuru Senda. (2018). Kodomo wo hagukumu kankyou [Environments That Nurture Children and Those That Damage Children]. Asahi Shimbun Publications Inc., Tokyo.

- Sporrel, K., Caljouw, S., & Withagen, R. (2017). Children prefer a nonstandardized to a standardized jumping stone configuration: Playing time and judgments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 53, 131-137.

- Masashi Sumiya. (2020). Hoikusho entei no keishatsuki sunabaga enji ni ataeru asobi no kikai [Play of Young Children Reflects Affordance in Sandpit]. Japanese Journal of Ecological Psychology.

- Shintaro Terada. (2010). Chapter 1: Kawawa hoikuen kiken wo toozakerunodewa naku kiken wo kanjitori taiken surukotoga jibun no mi wo mamoru chikara wo sodateru [Kawawa Nursery School Case: Feeling and experiencing danger can foster children's self-defense skills]. pp.7-46. Kodomo to oya ga ikitakunaru en anshin kosodate sukoyaka hoiku raiburari (3)[Kindergartens that are attractive for both children and parents. Healthy Child-Rearing Library (3): Study Case for Good Child-Rearing]. Masami Sasaki (edit). Subarusha, Tokyo.

- Shintaro Terada & Yoichi Miyahara. (2014). Futtemo haretemo: Kawawa hoikuen / Entei deno hibi to 113 no tsubuyaki [Kawawa Nursery School Case: Days of Rain and Sunshine in Kawawa Nursery School with 113 Tweets]. Shinhyoron, Tokyo.

Masashi Sumiya

Masashi Sumiya Tetsushi Nonaka

Tetsushi Nonaka