Introduction

As "natives" of the digital world, 21st century children live in a world where the Internet is ubiquitous. In recent years, digital device users have become younger and younger with the upsurge in the use of smartphones and tablets. It is reported that one third of 3-4-year-olds in the United Kingdom are using digital devices, and this figure is even higher in countries such as the Netherlands (78%), Belgium (70%) and Sweden (70%) (Holloway et al., 2013). In this context, smartphones, tablets and computers have become important learning tools for preschool children. The learning environment of preschool children has also shifted to one "combining the traditional learning environment and the digital learning environment."

At the same time, young children's learning style has changed. Online learning through digital devices such as smartphones, tablets and computers has entered the lives of preschool children as one way to learn. In January 2020, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the development of early childhood online education. A number of for-profit online course providers took advantage of this opportunity to launch various online courses for preschoolers as schools and offline educational institutions were closed due to the pandemic. Meanwhile, many parents were forced to choose online learning for their young children, which resulted in explosive growth of early childhood online education. By June 2020, preschools and offline education institutions were back to normal as the pandemic in China was gradually brought under control. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to investigate whether Chinese urban preschoolers have spent more time on online learning since the outbreak of COVID-19.

Young children's online learning

The term "online learning" is used to describe "learning experienced through the Internet with educational apps or in an asynchronous environment where students engage with teachers and students at a time of their convenience and do not need to be co-present online or in a physical space" (Singh & Thurman, 2019). Beginning in the 1990s with the advent of the Internet (Palvia et al., 2018), online learning has been controversial ever since, particularly with regard to young children. There is a large body of literature indicating that the use of digital devices may be harmful to young children's physical health (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017; Cheung et al., 2017; Aston, 2018; Gottschalk, 2019) and mental well-being (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017; Gottschalk, 2019; Dempsey et al., 2020). For instance, findings from 715 UK infants and toddlers aged 6-36 months suggested a significant association between the frequency of digital screen use and sleep quantity (reduced total duration, reduced duration of night-time and increased daytime sleep), and longer sleep onset (Cheung et al., 2017). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued numerous policy statements with reference to digital screen time, first advising no screen use for children under the age of two (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001). On the other hand, some statements point out that online learning through digital devices such as smartphones and tablets brings opportunities for young children's learning and development, suggesting that online learning has a positive impact on young children's emergent literacy and language development (Plowman et al., 2008; Hisrich & Blanchard, 2009; Lieberman et al., 2009; Plowman et al., 2010; Dore et al., 2019; Griffith et al., 2019; Neumann, 2014, 2018, 2020;), mathematic skills (Plowman et al., 2008; Lieberman et al., 2009; Plowman et al., 2010; Griffith, 2019); social skills (Kardefelt-Winther, 2017; Lawrence, 2018), and mental well-being (Plowman et al., 2008; Kardefelt-Winther, 2017), especially for those from disadvantaged background (Dore et al.,2019; Griffith, 2019). Furthermore, the "Goldilocks" hypothesis proposed by Przybylski and Weinstein claims that moderate use of digital devices is not harmful and can have a positive impact on children's mental well-being (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017). Even now, the debate over online learning for young children continues, though the young children's learning environment has turned into a new environment "combining the traditional learning environment and the digital learning environment" under the development of digital technology. Recent work indicates that one important reason for this inconsistency is that it fails to consider the heterogeneous nature of digital device uses and that different digital devices will not produce the same effects (Burns & Gottschalk, 2020).

In recent years, young children using digital devices have received a lot of attention with the rise in their use of digital technology. However, most of the studies have explored the risks and benefits of digital device use for young children, with few focusing on the content of digital device use and the types of screen time. So far, little attention has been paid to young children's online learning and online learning time. Moreover, studies on early childhood online learning are mostly conducted in countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. Therefore, this study aims to fill this research gap by investigating young children's online learning and online learning time in China.

Young children's online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged in Wuhan and other cities in China in late 2019. In March 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 as a pandemic (WHO, 2020). The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic exerted a great influence on all aspects of society. According to the OECD, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally disrupted schooling in most countries throughout the world (OECD, 2020). Online learning opportunities were elevated into a critical lifeline for education as a considerable number of schools shut down all over the world (OECD, 2020). In response to the school closure, the Ministry of Education in China launched a nationwide initiative entitled "disrupted classes, undisrupted learning," calling for providing guidance and service for primary and secondary school students' online learning with all the online platforms and resources (the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China, 2020). However, preschools were prohibited from carrying out any online learning activities. In spite of this, an increasing number of young children turned to online learning on account of the closure of preschools and offline educational institutions as well as the upsurge of online educational institutions for young children. By June 2020, preschools and offline educational institutions were back on track again as the pandemic in China had been gradually brought under control. In this context, it is important to explore the situation of young children's online learning since the pandemic and its impact on young children's online learning time. This study aims to address the following questions:

Did Chinese urban children have online learning experience after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic?

Have Chinese urban children spent more time on online learning since the pandemic?

Did Chinese urban children choose to continue online learning, or did their online learning time change when the pandemic was controlled or after schools reopened?

Method

ParticipantsParticipants in this study were parents of young children aged from 3 to 6 years, recruited from urban preschools in Chongqing, which is located in Southwest China. A total of 1,452 valid questionnaires were collected. The majority of the participants were mothers (75%, n=1,089). Most of the participants were aged between 30 and 40 years (60.1%, n=873). Most of their highest educational levels were junior high school and below (36.1%, n=524), high school/technical secondary school (24.7%, n=359), and undergraduate (20.8%, n=302). The majority of their household income per month was less than 10,000 yuan (70.2%, n=1,019). The background information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 Background information | ||

|---|---|---|

| Groups | N (%) | |

| Participant | Father | 311 (21.4) |

| Mother | 1,089 (75) | |

| Grandparent | 31 (2.2) | |

| Other caregivers | 21 (1.4) | |

| Age | Under 30 | 456(31.4) |

| 30-40years | 873(60.1) | |

| 41-50years | 95 (6.5) | |

| 51-60years | 25 (1.7) | |

| Over 60 | 3 (0.2) | |

| Educational level | Junior high school and below | 524(36.1) |

| High school/technical secondary school | 359(24.7) | |

| Junior college | 228(15.7) | |

| Undergraduate | 302(20.8) | |

| Postgraduate and above | 39 (2.7) | |

| Average household income per month | Less than 10,000 yuan | 1019(70.2) |

| 10,000-50,000 yuan | 372(25.6) | |

| 50,001-100,000 yuan | 39 (2.7) | |

| More than 100,000 yuan | 22 (1.5) | |

This study was investigated by a self-designed questionnaire "Young Children's Online Learning Questionnaire," which was reviewed and modified by experts in early childhood education and tested by parents to a certain extent. The questionnaire consists of four parts and includes 31 questions.

Part I: Background information. This part includes 7 questions, which aims to collect the basic demographic data such as gender, age and educational level of the parents and the basic demographic data of their children.

Part II: Young children's online learning in China. This part has 14 questions for the purpose of investigating young children's online courses, online learning time, online learning style, online learning effect etc., mainly focusing on young children's online learning and online learning time before and after the COVID-19 pandemic as well as young children's online learning and online learning time after the schools shut down and reopened.

Part III: Impact of online learning on young children. This part consists of 4 questions with the intention of ascertaining the impact of online learning on young children's development, screen time, outdoor time, and parent-child relationship.

Part IV: Parents' attitudes. This part aims to ascertain parents' attitudes towards young children's online learning with 6 questions.

ProcedureAn anonymous online survey was conducted in December, 2020. Prior to collection of the data, preschool educators from the urban area in Chongqing were informed about the research. Parents who were voluntary participants in the study were informed about the research purpose of this study and were given notes to fill out the questionnaire by the preschool educators thereafter. The online survey was completed by parents and collected on Wenjuanxing, a popular online survey platform in China. It was also guaranteed that the findings would be confidential and would be used for scientific research only.

AnalysisThe results collected in this research were analyzed by SPSS 25.0 software.

Results

1. Young children's online learning in Chongqing, China(1)Overview of young children's online learning in Chongqing, China

| Table 2. Overview of young children's online learning in Chongqing, China | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Never learned online | 29.5%(428) | 18.8% (273) | 21.6%(314) | 69.9% (1,015) |

| Have learned online before | 3.4% (49) | 3.8% (55) | 3.8% (55) | 11.0% (159) |

| Still learning online | 7.2% (105) | 5.9% (85) | 6.1% (88) | 19.1% (278) |

Table 2 shows the general situation of young children's online learning in Chongqing, China. Overall, the majority of the participants (69.9%, n=1,015) reported that their children had never learned online before, and only 30.1% of the participants (n=437) reported that their children had online learning experiences, which indicated that online learning was an important way for young children to learn in China even though it was not widely accepted. For children who had never learned online before (n=1,015), 42.1 % of them (n=428) were children between 3 and 4 years, suggesting that the younger the age of the children, the lower the acceptance for online learning was. For children reported to have had online experiences (n=437), 63.6% of them (n=278) were still learning online, which suggested that online learning was well recognized among young children after they started it, especially for children from 3 to 4 years. Undoubtedly, further investigation is needed to find out whether it is or not, because the time they started online learning was later than children from 4 to 6 years.

(2) Online courses taken by young children

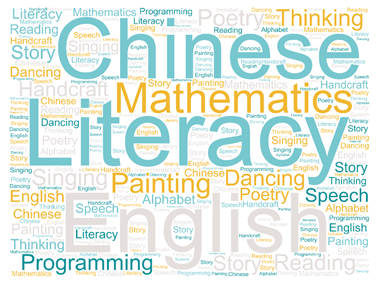

As can be seen in Figure 1, online courses taken by young children in Chongqing were mainly literacy, Chinese, painting, English, mathematics, programming, thinking, etc. A large number of children chose online courses like literacy, Chinese, mathematics and English, which indicated that parents of young children in China paid more attention to children's intellectual education in terms of online learning content.

(3) Time when young children start and stop online learning| Table 3. Time when young children started online learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Before January 2020 | 9.2% (40) | 13.3% (58) | 13.0% (57) | 35.5% (155) |

| January-June 2020 | 13.0% (57) | 13.0% (57) | 14.0% (61) | 40.0% (175) |

| After June 2020 | 13.0% (57) | 5.7% (25) | 5.7% (25) | 24.5% (107) |

In Table 3, 35.5% (n=155) of the participants reported that their children started online learning before January, 2020, 40% (n=175) of the participants reported that their children began online learning from January to June of 2020, and the remaining participants (24.5%, n=107) reported that their children started learning online after June, 2020. Among these young children, a large proportion of them (64.5%, n=282) started online learning after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which indicated that the number of children learning online increased considerably after the outbreak of the pandemic and the school closure. At the same time, 35.5% of young children started online learning before January, 2020, which suggested that online learning became more and more common for young children in the digital learning environment.

| Table 4. Time when young children stopped online learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Still learning online | 24.0% (105) | 19.5% (85) | 20.1% (88) | 63.6% (278) |

| Before January 2020 | 2.1% (9) | 1.1% (5) | 2.1% (9) | 5.3% (23) |

| January-June 2020 | 2.7% (12) | 6.4% (28) | 3.2% (14) | 12.4% (54) |

| After June 2020 | 6.4% (28) | 5.0% (22) | 7.3% (32) | 18.8% (82) |

As can be observed in Table 4, of all the participants, 63.6% (n=278) reported that their children were still learning online, 18.8% (n=82) reported that their children stopped online learning after June, 2020, 12.4% (n=54) reported that their children stopped learning online from January to June of 2020, and 5.3% (n=23) stopped before January, 2020. According to the data in Table 4, the number of young children who stopped online learning after June, 2020 was more than those before June, 2020, suggesting that young children seemed to have stopped learning online when the COVID-19 pandemic had been further controlled and preschools and offline educational institutions were back on track again. In addition, 63.6% of young children were still learning online, which indicated that online learning was highly recognized by parents and young children.

(4) The Average time young children spend on online learning before and after school reopening| Table 5. Average time young children spent on online learning before schools reopened | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| 0 | 6.2% (27) | 5.5% (24) | 5.7% (25) | 17.4% (76) |

| 1-15 min | 12.6% (55) | 9.4% (41) | 7.1% (31) | 29.1% (127) |

| 16-30 min | 13.0% (57) | 11.9% (52) | 13.5% (59) | 38.4% (168) |

| 31 min-1h | 2.5% (11) | 4.1% (18) | 6.2% (27) | 12.8% (56) |

| more than 1 h | 0.9% (4) | 1.1% (5) | 0.2% (1) | 2.3% (10) |

| Table 6. Average time young children spent on online learning after schools reopened | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| 0 | 8.0% (35) | 6.2% (27) | 8.2% (36) | 22.4% (98) |

| 1-15 min | 10.3% (45) | 10.3% (45) | 7.8% (34) | 28.4% (124) |

| 16-30 min | 14.0% (61) | 11.9% (52) | 11.7% (51) | 37.5% (164) |

| 31 min-1h | 2.3% (10) | 2.7% (12) | 4.3% (19) | 9.4% (41) |

| more than 1 h | 0.7% (3) | 0.9% (4) | 0.7% (3) | 2.3% (10) |

As can be seen from Table 5 and Table 6, a lot of young children spent 1-15 minutes and 16- 30 minutes on online learning per day, with the majority learning online for 16-30 minutes per day. Comparing Table 5 and 6 shows that little change was found in terms of the average time young children spent on online learning for 1-15 minutes, 16-30 minutes and more than 1 hour per day before and after the reopening of the preschools and offline educational institutions. However, the percentage of young children who didn't learn online increased by 5% and the percentage of young children who spent 31 minutes to 1 hour on online learning per day decreased by 3.4%, indicating that the average online learning time per day decreased slightly after schools reopened, especially for children from 5 to 6 years.

2. Impact of online learning on young children(1) Impact of online learning on young children's development

| Table 7. Impact of online learning on young children's development | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor development | Cognitive development | Emotional development | Personality development | Language development | Total | |

| 3-4 years | 7.2%(64) | 11.6%(103) | 4.2% (37) | 3.5%(31) | 10.2%(91) | 36.6%(326) |

| 4-5 years | 5.3%(47) | 11.2%(100) | 3.7% (33) | 2.5%(22) | 9.3% (83) | 32.0%(285) |

| 5-6 years | 4.7%(42) | 9.7% (86) | 3.8% (34) | 3.1%(28) | 10.0%(89) | 31.3%(279) |

| Note. Number of impacts on children's development was limited to three options, which causes the total percentage to exceed 100%. | ||||||

According to Table 7, most of the participants believed that online learning had a positive impact on their children's cognitive development (32.5%, n=289) and language development (29.6%, n=263), which indicated that online learning had a positive impact on young children's cognitive development and language development, and it had little impact on children's motor development, emotional development and personality development. However, this may be related to the type of online courses chosen by young children (see Figure 1).

(2) Young children's screen time after online learning| Table 8. Young children's screen time after online learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Increased a lot | 7.6% (33) | 4.3% (19) | 5.0% (22) | 16.9% (74) |

| Increased a little | 13.3% (58) | 10.5% (46) | 11.4% (50) | 35.2% (154) |

| No change | 10.5% (46) | 10.1% (44) | 11.4% (50) | 32.0% (140) |

| Decreased a little | 3.0% (13) | 4.6% (20) | 3.2% (14) | 10.8% (47) |

| Decreased a lot | 0.9% (4) | 2.5% (11) | 1.6% (7) | 5.0% (22) |

| Note: The table represents the results of young children's screen time apart from online learning. | ||||

Young children's screen time besides online learning after they started learning online is given in Table 8. As displayed in Table 8, a majority of participants (52.1%, n=228) reported that their children's screen time increased, 32% of the participants (n=140) reported that their children's screen time remained constant, and a small proportion of the participants (15.8%, n=69) reported that their children's screen time decreased after learning online, which indicated that young children's dependence on digital devices increased significantly after learning online.

(3) Young children's time for outdoor activities after online learning| Table 9. Young children's time for outdoor activities after online learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Increased a lot | 5.9% (26) | 2.7% (12) | 3.9% (17) | 12.6% (55) |

| Increased a little | 9.4% (41) | 6.9% (30) | 7.1% (31) | 23.3% (102) |

| No change | 15.1% (66) | 15.8% (69) | 15.1% (66) | 46.0% (201) |

| Decreased a little | 4.8% (21) | 5.5% (24) | 5.9% (26) | 16.2% (71) |

| Decreased a lot | / | 1.1% (5) | 0.7% (3) | 1.8% (8) |

Young children's time for outdoor activities after online learning is presented in Table 9. From Table 9 it can be seen that a large proportion of the participants (46%, n=201) reported that their children's time for outdoor activities remained constant after learning online, 35.9% of the participants (n=157) reported that their children spent more time on outdoor activities, and only 18% of the participants (n=79) reported that their children's outdoor time decreased. It is worth noting that although it can be seen from Table 5, Table 6 and Table 8 that young children spent much more time on online learning and other digital devices per day, 46% of young children's outdoor time remained constant and 35.9% of young children's outdoor time even increased in Table 9. This indicated that not only did most children's outdoor time not decrease with the increase of screen time, it increased, reflecting that parents tended to ensure young children played outdoors when their children spent a lot of time on digital devices.

3. Parents' attitudes towards young children's online learning| Table 10. Whether to continue online learning when the pandemic is controlled or after the pandemic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | 4-5 years | 5-6 years | Total | |

| Yes | 27.0% (118) | 22.9% (100) | 22.7% (99) | 72.5% (317) |

| No | 8.2% (36) | 9.2% (40) | 10.1% (44) | 27.5% (120) |

As indicated in Table 10, a large proportion of the total (72.5%, n=317) reported that their children would continue learning online when the pandemic was controlled or after the pandemic, which showed that online learning was highly recognized by parents and young children, especially for children between 3 and 4 years (27%, n=118), whilst a small proportion of the total (27.5%, n=120) would not choose online learning for their children any more, especially for children between 5 and 6 years (10.1%, n=44).

| Table 11. Reasons for continuing online learning | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guaranteed online course quality | Children like it | Convenience | Low price | Concern about the pandemic | Other | Total | |

| 3-4 years | 4.4% (27) | 13.3%(82) | 9.1% (56) | 3.9%(24) | 3.6%(22) | 2.4%(15) | 36.6%(226) |

| 4-5 years | 4.2% (26) | 11.7%(72) | 10.2%(63) | 2.9%(18) | 2.4%(15) | 1.1% (7) | 32.6%(201) |

| 5-6 years | 4.7% (29) | 10.4%(64) | 9.7% (60) | 2.3%(14) | 1.9%(12) | 1.8%(11) | 30.8%(190) |

| Note: The results in the table were collected only from parents whose children would continue online learning. Number of reasons was limited to three options, which causes the total percentage to exceed 100%. | |||||||

The reasons why parents continued to choose online learning are reported in Table 11. Overall, a great proportion of the parents (35.3%, n=218) continued to choose online learning for their children because their children liked it, which suggested whether parents continued to choose online learning for their children mainly depended on whether their children liked it or not, especially for parents of children aged 3-4. Among parents of children aged 4-5 and 5-6, the proportion of "convenience" was close to the proportion of "children like it," which indicated that whether these parents continued to choose online learning for their children depended on whether their children liked it or not and the convenience of online learning. However, only a small proportion of participants (7.9%, n=49) chose "concern about the pandemic," which suggested that although the COVID-19 pandemic had a certain degree of influence on whether young children would continue online learning or not, the influence was insignificant.

| Table 12. Reasons for not continuing online learning | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissatisfied with online course quality | Children don't like it | Concern about children's physical health | Concern about children's mental health | High price | The domestic pandemic is under control | Other | Total | |

| 3-4 years | 5.0% (10) | 3.5% (7) | 8.9% (18) | 3.5% (7) | 4.0% (8) | 2.5% (5) | 3.5% (7) | 30.7% (62) |

| 4-5 years | 5.0% (10) | 5.4%(11) | 10.4%(21) | 5.0%(10) | 2.0% (4) | 1.0% (2) | 4.5% (9) | 33.2% (67) |

| 5-6 years | 7.4% (15) | 5.4%(11) | 10.9%(22) | 2.5% (5) | 4.0% (8) | 0.5% (1) | 5.4%(11) | 36.1% (73) |

| Note. The results in the table are collected only from parents whose child would not continue online learning. Number of reasons was limited to three options, which causes the total percentage to exceed 100%. | ||||||||

The reasons why parents would not continue to choose online learning are presented in Table 12. Overall, a significant proportion of the parents (30.2%, n=61) were concerned about children's physical health, indicating that, for parents of children aged 3-6, the main reason why they would not continue online learning was that they feared that online learning would be harmful to young children's health. In addition to "concern about children's physical health," a large proportion of participants were dissatisfied with the online course quality, which suggested that the quality of online courses would also be taken into account when deciding whether or not to continue online learning. However, "the pandemic is under control" was rarely taken into account by the participants, which again reflected that the COVID-19 pandemic had little influence on whether young children would continue online learning or not.

Conclusion

This study suggested that Chinese urban children's online learning time and opportunities have both increased since the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. Though it exhibited a declining trend after the pandemic was controlled and schools reopened, most of the young children were still learning online. This study investigated young children's online learning time after the pandemic in urban areas of China for the first time, providing information for understanding the online learning situation of young children in China in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study also provides some implications for policy makers and educators regarding young children's online learning. However, this study has the following limitations. First, this study only investigates the online learning situation of young children from 3 to 6 years in Chongqing. A nationwide sample should be collected and the data of children aged from 0 to 3 years should also be collected in a future study as comprehensive research data is needed to provide stronger evidence. Second, this study simply investigates with a questionnaire. Mixed methods are needed for in-depth investigation of young children's online learning in the future. Further research is needed to find out how these experiences influence young children's learning and development and whether this will have a more profound change on young children's learning style or learning environment.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Public Education. (2001). Children, Adolescents, and Television. Pediatrics, 107(2), 423-426. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.2.423

- Aston, R. (2018). Physical health and well-being in children and youth: Review of the literature. OECD Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1787/102456c7-en - Burns, T., & Gottschalk, F. (2020). Education in the digital age: Healthy and happy children. OECD Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1787/1209166a-en - Cheung, C. H., Bedford, R., De Urabain, I. R. S., Karmiloff-Smith, A., & Smith, T. J. (2017). Daily touchscreen use in infants and toddlers is associated with reduced sleep and delayed sleep onset. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46104 - Dempsey, S., Lyons, S., & McCoy, S. (2020). Early mobile phone ownership: influencing the wellbeing of girls and boys in Ireland?. Journal of Children and Media, 14(4), 492-509.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1725902 - Dore, A. R., Shirilla, M., Hopkins, E., Collins, M., Scott, M., Schatz, J., Lawson-Adams, J., Valladares, T., Foster, L., Puttre, H., Toub, S. T., Hadley, E., Golinkoff, M. R., Dickinson, D., & Hirsh-Pasek, K., (2019). Education in the app store: Using a mobile game to support U.S. preschoolers' vocabulary learning. Journal of Children and Media, 13(4), 452-471.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2019.1650788 - Gottschalk, F. (2019). Impacts of technology use on children: Exploring literature on the brain, cognition and well-being. OECD Publishing.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/8296464e-en - Griffith F. S., Hanson, G. K., Rolon-Arroyo, B., & Arnold, H. D., (2019). Promoting early achievement in low-income preschoolers in the United States with educational apps. Journal of Children and Media, 13(3), 328-344.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2019.1613246 - Hisrich, K., & Blanchard, J. (2009). Digital Media and Emergent Literacy. Computers in the Schools, 26(4), 240-255.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07380560903360160 - Holloway, D., Green, L., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Zero to eight: Young children and their internet use. EU Kids Online.

https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2013/929/ - Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2017). How does the time children spend using digital technology impact their mental well-being, social relationships and physical activity? An evidence-focused literature review. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti.

- Lawrence, M. S. (2018). Preschool Children and iPads: Observations of social interactions during digital play. Early Education and Development, 29(2), 207-228.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1379303 - Lieberman, A. D., Bates, H. C., & So, J. (2009). Young children's learning with digital media. Computers in the Schools, 26(4), 271-283.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07380560903360194 - Neumann, M. M. (2014). An examination of touch screen tablets and emergent literacy in Australian pre-school children. Australian Journal of Education, 58(2), 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944114523368

- Neumann, M. M. (2018). Maternal scaffolding of preschoolers writing using tablet and paper-pencil tasks: Relations with emergent literacy skills. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 32(1), 67-80.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1386740 - Neumann, M. M. (2020). The impact of tablets and apps on language development. Childhood Education, 96(6), 70-74.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2020.1846394 - Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (2020, March 6). The deployment of "suspended class, ongoing learning" for primary and secondary school students. Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (In Chinese)

http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/202003/t20200306_428342.html - OECD. (2020). Coronavirus special edition: Back to school. OECD Publishing.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/339780fd-en - OECD. (2020, April 3). Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA. OECD.

https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/learning-remotely-when-schools-close-how-well-are-students-and-schools-prepared-insights-from-pisa-3bfda1f7/ - Palvia, S., Aeron, P., Gupta, P., Mahapatra, D., Parida, R., Rosner, R., & Sindhi, S. (2018). Online education: Worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 21(4), 233-241.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2018.1542262 - Plowman, L., McPake, J., & Stephen, C. (2008). Just picking it up? Young children learning with technology at home. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(3), 303-319.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640802287564 - Plowman, L., Stephen, C., & McPake, J. (2010). Supporting young children's learning with technology at home and in preschool. Research Papers in Education, 25(1), 93-113.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520802584061 - Przybylski, A., & Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the Goldilocks hypothesis. Psychological Science, 28(2), 204-215.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797616678438 - Singh, V., & Thurman, A. (2019). How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988-2018). American Journal of Distance Education, 33(4), 289-306.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2019.1663082 - WHO. (2020, June 29). Listings of WHO's response to COVID-19. World Health Organization.

https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline

Lin-lian Gao

Lin-lian Gao Guimin SU

Guimin SU