I Introduction

1.1 Background

Play has a special role in our lifelong development (Bateson, 2011 and others). It is an invaluable part of children's mental and physical activities and provides a foundation for learning in their middle childhood and beyond (Brown, 2010; Gray, 2013). In fact, children's play has been uniquely defined in different fields including philosophy, psychology, education, early childhood education, etc. (Pelligrini, 2011; Smith & Roopnarine, 2019, and others). Researchers today regard children as actors and are more interested in their perspectives on their playful activities. Children's play has been widely studied for decades from several academic perspectives (Piaget, 1962; Vygotsky, 1978; Erikson, 1950, and many others) and their developmental, psychosocial, and adaptive benefits have been emphasized. The importance of playfulness in educational settings has also gained much attention, and many play-based programs are designed by education professionals and policy makers. However, these are based on adults' perceptions whereas children's play must be studied from children's perspectives (McInnes, 2013). In this regard, there are few research studies or findings. Children's perspectives are necessary for educational practices to be ecologically valid and effective (Barnett, 2013).

The mosaic approach is a framework that combines different modes of communication such as speech and visual information to listen to children's voices (Clark & Moss, 2011). This integrated approach emphasizes the importance of the use of ordinary and familiar tools for children and treats a young child as a perfect communicator; it procures children's perspectives using various simple and accessible visual and auditory mechanisms. It combines different kinds of information from children as pieces of a mosaic to acquire an overall understanding of their perceptions and perspectives.

In Japan, studies using this approach have accumulated their findings. We know that children in Japanese Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) settings prefer playing in certain places that have some common characteristics. For instance, Miyamoto et al. (2016) pointed out three physical features and eight functional features that children particularly prefer.

We are also aware of the discrepancy between preschool children's perceptions of play and those of their teachers (Sugimoto et al., 2019). In their favorite play space, children engage in various activities--physical and mental. For them, merely observing or watering flowers in the garden could be play; merely looking at their favorite paintings on the wall of their classroom could be play. What makes them call such activities play? While previous studies have found some representative characteristics of children's preferences, it is still unknown how children feel in their favorite places, what they do there, and what they learn from their favorite activities.

The mosaic approach enables listening to children's opinions, making it possible to closely study their individual differences, to better understand their perceptions so as to create an improved, more playful learning environment for them. In the present study we are interested in investigating the factors that affect children's perceptions of their favorite places to play.

1.2 Purpose of the present study

The purpose of this research is to explore how preschoolers perceive and value their favorite places to play within the framework of the mosaic approach.

We used the academic task-value scale developed by Ida (2001), which is generally used to examine the academic motivation of learners in middle childhood and beyond. It should be interesting to see the applicability of the scale to preschoolers' values and perceptions.

There are five research questions. First, how many favorite places do four- and five-year-olds have in their school? Second, what kind of activities do children enjoy in their favorite places in relation to their task-values? Third, what kinds of values do preschoolers assign to their favorite places? Are there any individual differences? Fourth, do children assign particular task-values to specific places? Fifth, what factors are likely to influence children's individual differences in the formation of their task-values?

II Methods

2.1 Procedure

A total of 93 four- to five-year-olds from two preschools in central Japan participated in our study. Based on the purposeful sampling method, which allowed us to control the environmental variations, we chose two preschools with similar physical environment and childcare policies from two medium-sized cities in central Japan.

Two groups of children participated in the research from January to March, which marks the final period of the Japanese academic calendar.

Following Miyamoto et al. (2017), the framework of the mosaic approach was used for the research. In the photo projection method, children were asked to take photos of their favorite places in their school. Then, quasi-structured interviews were conducted with each child using photos taken by the children--questions included why they like the places and what they do there. They were also asked to rank their favorite places and assign reasons for their preferences.

2.2 Measures and scoring

Children assign different types of task-values to their favorite places where they play.

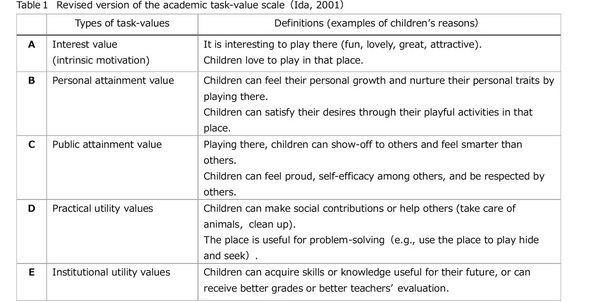

Table1 Revised version of the academic task-value scale (Ida, 2001)

The academic task-value scale was originally developed to measure students' perceptions of and attitudes toward academic tasks provided by teachers in classroom activity or homework assignment (Ida, 2001). It is designed to be evaluated on a seven-point Likert scale. For preliterate preschoolers, we made this scale binary: i.e., yes or no and qualitatively analyzed children's answers and comments based on this scale. We awarded one point if a participant gave the definitions. If not, then no point was awarded. Therefore, either one point or zero was awarded for each place that the children chose. Finally, we calculated the score and performed statistical analyses. More than one kind of value can be given to each place.

III Results and discussion

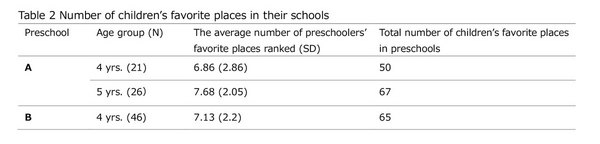

A combination of a picture-projection method and interview data reveals that four- to five-year-old children have, on average, 7 favorite places to play in their school (Table 2). They could also rank their favorite places in their school.

Table 2 Number of children's favorite places in their schools

3.1 Children's value assignment on their favorite places in their schools

The scoring was based on Table 1. For each task-value per place, we awarded one point (e.g., the chin-up bars -> personal attainment value one point). Each place received more than one task-value, depending on children's value assignment (e.g., the rabbit house -> interest value and practical utility value).

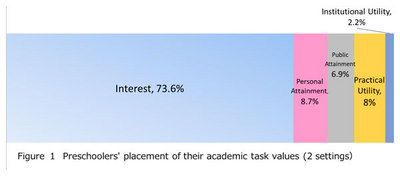

Our results show that children found interest value in 73.6 percent of their favorite places, i.e., the places are interesting and funny to play in; they also found other task-values such as personal attainment and practical utility values (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Preschoolers' placement of their academic task values (2 settings)

3.2 Patterns of preschoolers' value assignment and childcare policy

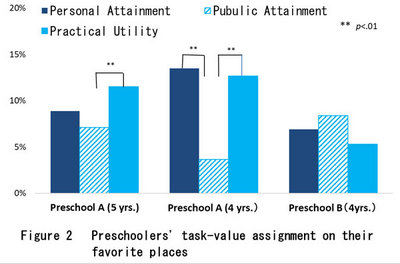

Both four-year-olds and five-year-olds could name and rank up to seven of their favorite places in their school (Table 2 above). We analyzed the preschoolers' value assignment on their top five favorite places. Results of a three-way ANOVA (Task-value(3: personal attainment / public attainment / practical utility)∗Preschool(2)∗Gender(2)) show a significant first-order interaction of task-value and preschool (F(4,60)=4.24, p<.001, sig., η2 = .220). The significant main effect of task value (F(4,60)=70.265, p<.001, sig.,η2= .824). A significant main effect of preschool on Personal growth and Practical utility was also found (Personal attainment value: Preschool A > Preschool B; Practical utility value: Preschool A > Preschool B; the significant main effect of Interest on task-value; Preschool A: Interest > Personal Growth≒ Practical utility. Preschool B: Interest > Practical utility > Personal growth ≒ Practical utility). However, no significant gender effect was found.

Children's task-value assignment patterns varied between the two preschools. Children in preschool A were more likely to assign personal attainment and practical utility values than public attainment value. On the other hand, children in preschool B assigned the three task-values indifferently. We found no significant main effect of the task-value on children in preschool B.

Figure 2 Preschooler's task-value assignment on their favorite places

3.3 Practical utility value and the childcare policy of preschool A

Children in preschool A were likely to assign the practical utility value to their favorite place to play. In this preschool, children routinely cleaned the floor of the open deck and took turns to look after rabbits. Five-year-old children in this preschool are in-charge of cleaning. Teachers do not interfere or instruct and support the children whenever needed. Interestingly, 9 children chose the open deck as one of their favorite places because they enjoyed cleaning the floor with a cloth. We conclude that cleaning could play a role in children's identification of a place as interesting or fun. Preschoolers do enjoy cleaning public places or taking care of animals for the preschool, and children feel such places have a practical utility value.

Similarly, 14 children in preschool A favored the rabbit house where they enjoyed meeting and observing the rabbits, and they taking care of them. They found in the place both interest value and practical utility value. They were proud of taking care of the rabbits and cleaning the rabbit house. For them it was a kind of play rather than routine work.

3.4 Variations in children's value assignment on their favorite places

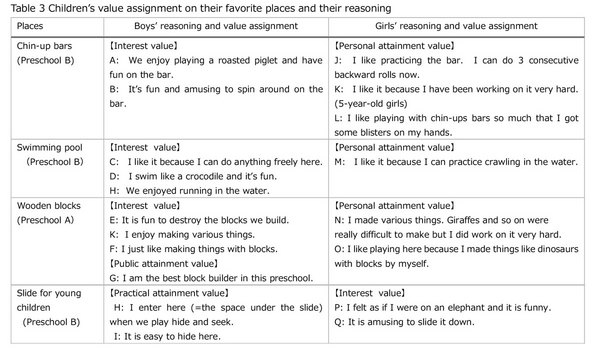

Children assign different task-values to the same place, even though they play together. Table 3 shows cases where boys and girls have assigned different types of values to their favorite places within the same ECEC setting. In some places, boys find interest value while girls find some other kind of values, such as personal attainment value. However, we need to further investigate such differences with a larger sample of preschools and children.

Table 3 Children's value assignment on their favorite places and their reasoning

3.5 Children assigning values other than the interest value

The following two cases show that children favor other task-values than the interest value of the place. In case A, a girl values her own personal attainment or growth, which seems to be influenced by her mother's values. In case B, a boy prefers competitive places and plays and so favors public attainment value, which seems to be influenced by his father's values.

Case A: A child emphasizing the personal attainment value

Some children from the two preschools had values other than the interest value. In particular, a girl from preschool A had the personal attainment value in most of her favorite places, for example, the chin-up bars, the playground, and the easy-made planter for Japanese radish (Figure 3). She liked the chip-up bars because she wanted to practice and improve flipping on the bar.

She also liked the easy-made planters as she liked to watch vegetables grow and wanted to eat them to be healthier and bigger. She said that her mother told her about the importance of balanced diets, including vegetables, for good health and growth. Her mother's parenting and values seemed to affect her preferences for places and behavior. Figure 3 A girl's favorite easy-made planter for Japanese radish in preschool A

Figure 3 A girl's favorite easy-made planter for Japanese radish in preschool ACase B: A child emphasizing the public attainment value

On the other hand, a boy from preschool B placed public attainment values on most of his favorite places where he could compete with other children, such as the playground and the puzzles in his senior fellows' classroom, and Shogi. For him, it was fun to win. He preferred competitive plays and situations in his school as well as at home. He not only enjoyed competing with his friends, but also enjoyed playing games such as Shogi and Othello with his father at home. He seemed to share the public attainment value with his father, which in turn may have affected his own preference for places to play in his school.

In summary, these two cases suggest that some preschoolers find the personal attainment value or the public attainment value more important than the interest value, and that children's relationship with their family and shared values may affect their decisions related to assigning of task-values.

IV Summary and conclusion

The present study found the following characteristics of preschoolers' perceptions and values of play and playground. First, in general preschoolers had about seven favorite places to play in their schools and uniquely assigned task-values to their favorite places to play. Even if children played together, they found different meanings and values in their favorite places to play, based on their unique perceptions and motivations. Second, preschools' play environment and their childcare policies could impact the value that children assign to places to play. Children are likely to assign the personal attainment value to such places where they can play freely and with autonomy. Children may find the practical utility value in places where they can experience prosocial activities such as taking care of animals and cleaning public spaces.

As the children assigned interest value to about 74 percent of their favorite places, they were intrinsically motivated to play in their favorite places. However, at the same time, they could also have some extrinsic motivations such as public attainment and practical utility in their favorite playgrounds. (e.g., children prefer places where they can feel competent; they can feel their self-efficacy; they can act freely to reach their goals.) As for the limitations of the current study, we could not qualitatively show gender differences in children's value assignment to their favorite places. For that, we need substantive data from children in different types of institutions.

[References]

- 1. Bateson, P. (2011). Theories of Play. In Pellegrini, A. D., (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 2. Brown, S. (2010). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Avery.

- 3. Clark, A. & Moss,P. (2011). Listening to Young Children:The Mosaic Approach. Second edition. National Children's Bureau.

- 4. Gray, P. (2013). Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-reliant, and Better Students for Life. Basic Books.

- 5. Hunleth, J. (2011). Beyond on or with: Questioning power dynamics and knowledge production in 'child-oriented research methodology. Childhood 18(1). pp81-93.

- 6. Ida, K.(2001). An Attempt to Construct the Academic Task Values Evaluation Scale. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Nagoya University (Psychology and Human Development Sciences) 48, pp83-95.

- 7. Miyamoto, Y., Akita, K., Tsujitani, M., & Miyata, M. (2016) Preschool children's perception of place to play: using photo projection method by children.The Japanese Journal for the Education of Young Children 25. pp9-21.

- 8. Miyamoto, Y., Akita, K., Sugimoto, T., Tsujitani, M.,& Miyata, M. (2017) Preschool teachers' perceptions of children's play space. International Early Childhood Education 24. pp 61-76.

- 9. McInnes,K., Howard,J., Crowley,K. & Miles,G. (2013). The nature of adult-child interaction in the early years classroom: Implications for children's perceptions of play and subsequent learning behavior. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 21. pp268-282.

- 10. Moore, D. (2015). 'The teacher doesn't know what it is, but she knows where we are': young children's secret places in early childhood outdoor environments. International Journal of Play 4(1). pp20-31.

- 11. Pellegrini, A. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 12. Smith, P.K. & Roopnarine, J.L. (2019). The Cambridge Handbook of Play: Developmental and Disciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 13. Sugimoto, T., Akita, K., Miyamoto, Y. Miyata, M., Tsujitani, M. Ishida, K.(2018). An investigation into preschoolers' values on their favorite places to play. The proceedings of the 15th annual meeting of Child Science. p38.

- 14. Sugimoto, T., Akita, K., Miyamoto, Y. Miyata, M., Tsujitani, M. Ishida, K. (2019). Some aspects of preschoolers' and teachers' perceptions of places to play: variations in preferences and multiplicity of viewpoints-. Child Science 17. pp31-36.

Acknowledgement

The author is very grateful to the teachers, the children, and their parents who helped us pursue our research. This research is a part of the collaborative research with Kiyomi Akita (Graduate School of Education, the University of Tokyo); Yuta Miyamoto (Graduate School of Education, the University of Tokyo & JSPS); Mariko Miyata (Shiraume Gakuen University); Machiko Tsujitani (Shiraume Gakuen University & JSPS); and Kaori Ishida (Preschool Outdoor Environment Design Office).

This study was financially supported in part by Cedep (Center for Early Development & Early Childhood Education and Policy Research) at the University of Tokyo (SEED Project 2015-2019; Project leader: Kiyomi Akita).