Introduction

Along with the consumption tax rate hike planned for October 1, 2019, the Free Preschool Education and Care program is about to be introduced. Since Japan experienced a so-called "1.57 shock" in 1989 when the total fertility rate recorded a new record low. The former record low occurred in 1966, and in response the government instituted the "Angel Plan" as one of the countermeasures to the falling birthrate. Yet again, in 2005, the rate fell to 1.26, the lowest in recorded history. Since then, a slight increasing trend has been maintained, but in 2017 the rate was still low at 1.43*1. With respect to the total fertility rate by prefecture, Tokyo recorded the lowest of 1.21*2 compared to other prefectures, decreasing below the rate of 1.24 in the previous year*3. To solve the issue of declining birthrates, the "New Economic Policy Package"*4 and the "2018 Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform"*5 were approved by the Cabinet on December 8, 2017 and June 15, 2018, respectively. Preschool education and daycare services will be soon be made free for all children aged between 3 and 5 who attend kindergartens, daycare centers, and accredited children centers.

Despite Japan's declining birthrate, which has become a social issue, the number of childcare facilities is still inadequate. The number of double-income families that need childcare services is increasing due to an increase in female employment. There are about 20,000 children nationwide who are on a waiting list*6. The phenomenon of young children on waiting lists for childcare facilities has become a serious issue in Japan, particularly in metropolitan areas. The Japanese government has set a goal of guaranteeing a high level of early childhood education for all children, by decreasing the financial burden of education costs on parents. They are also determined to resolve the issue of children's waiting lists and the M-shaped curve phenomenon where women tend to leave the labor force due to childbirth and childrearing ("Childrearing Reassurance Plan" in 2017)*7. Nevertheless, there are still some unresolved issues such as a shortage of childcare workers due to their arduous working conditions and the need to improve the general caliber of staff. Ikemoto (2018)*8 pointed out that the Free Preschool Education and Care program was somewhat biased toward reducing financial burdens as one of the countermeasures to declining birthrates, lacked sufficient discussion to ensure the content and quality of early childhood education, and would bring about longer childcare hours due to the launch of Free Preschool Education and Care. According to the "Survey on Marriage and Family Formation" by the Cabinet Office (2014)*9, the top answer of the respondents (68.6%) to the question "What factors would make you feel you want to have (more) children?" was "Support for future education costs" and the second top answer (59.4%) was "Support for the costs of kindergarten and daycare centers." Based on these results, the government formulated the Free Preschool Education and Care program as one of the important measures to counteract the declining birthrate, reasoning that young generations hesitate to have children because of the "high costs of childrearing and education."

Without doubt, raising children costs a lot of money in Japan. However, the issue is not so clear-cut. Support for the costs of kindergarten and daycare centers will not instantly make parents feel they would like to have one more child. Some parents say they have enough children and want to earn as much money as possible to secure their future (Seki, Nishiwaki, and Bekki, 2019)*10. Shibata (2016)*11 pointed out the importance of enhancing childrearing support services, insisting that enhanced childrearing support will improve Japan's labor productivity and economic growth, and hence, improve birthrates. What kinds of childrearing practices and life course do parents wish for? What factors will satisfy their needs to achieve their aspirations? And what do they think about the Free Preschool Education and Care program? For new parents, how will the program affect their choice for children's living conditions and their own life course, for example, until what age they spend time with their child at home, when they go back to work, and which childcare facility they will choose for their child? Ishiguro (2011) mentioned the arguments on Bourdieu's theory by S.J. Ball, stating that "National policies suggest practical choices for childrearing and education, which parents will face while attempting to make a compromise with their childrearing perceptions. Therefore, these choices represent a momentum where macro-level policies by the government are linked to micro-level practices by citizens."*12

According to the qualitative research surveys on the selection of childcare facilities which I conducted through interviews with parents in 2016 and 2017 (Seki, 2018a/2018b)*13, it is revealed that families have different conditions, and parents have different points of views and desires when selecting a childcare facility. Factors closely related to parents' choice of facilities include families' economic conditions, mothers' employment status, the existence of support by someone close to them, the degree of convenience and the quality of education; however, these factors do not necessarily apply to every family. Some parents are obliged to make a limited choice for unavoidable reasons. Some think they want to spend time with their child when the child is very young, regardless of whether they have a job or not. Others are not very much concerned about how long they will stay with their child at home. Some parents want a kindergarten with a large playground where their child can run around. Others want their child to learn English. When making a choice about until what age to spend time with their child at home, at what age to enroll the child in daycare, etc., parents of young children will realize their expectations towards their child and perceptions of childrearing as well as their life course, all of which they have never thought about clearly before. Then, they make a choice according to their family's and child's actual conditions. The surveys show that parents who answered, "I want to spend time with my child at home until the s/he is three years old" changed their mind when they had a second child and answered, "I want to start working when s/he is one or two years old." Some parents said they would feel economic insecurity if they had more children, or feel tired physically and mentally after spending time with their child in a closed living environment. How do parents determine, considering the conditions of their child, that it is enough for them to spend time with the child only until s/he is one or two years old? The Free Preschool Education and Care for children from zero to two years old is currently under discussion, and for the meantime, will be provided for tax-exempt households. The Free Preschool Education and Care program for young children may impact parents' perceptions of childrearing and choice of life course who previously thought they wanted to "spend time with the child while the child is very young."

Based on the above factors, I decided to conduct a survey with Yoshiko Bekki, who specializes in developmental psychology and statistical analysis on qualitative research, and Futaba Nishiwaki, who specializes in historical studies on childcare. The survey was intended to examine the impact of the Free Preschool Education and Care on parents' perceptions of childrearing and choice of their life course, focusing on certain questions such as "At which age will they want to enroll their child in daycare?" "When and how will they want to start working?" and "Will there be more parents who want to enroll their child in daycare even when the child is less than one year old?"

Methodology

Respondents

680 parents using ECEC centers (nintei kodomo en) and daycare centers (5 facility centers selected from one area with many wait-listed children and two areas with no child on the waiting list, from cities with a population of 200,000 or more in Tokyo and one prefecture)

Procedures

In July 2018, we explained about our survey to the directors of these childcare facilities and obtained their approval. They helped us distribute the questionnaire sheet to parents and collect the answers. The survey was conducted on an anonymous basis. We collected a letter of consent and the questionnaire sheet separately from parents. The number of respondents who answered the questionnaire was 309 (Collection rate: 45%; Area A: 117 respondents, Area B: 106 respondents, Area C: 86 respondents)

Questionnaire

The survey items included the attributes of the respondents, the timing of enrollment for the first child and the second child, and the prospective timing of enrollment when the Free Preschool Education and Care program is implemented (with the options of "After maternity leave ends," and when the child is "Less than six months old," "Six months or more and less than one year old," "Two years old," "Three years old" and "Four years old." In addition, for the question of at what age they want to enroll their child in childcare in the case of the implementation of Free Preschool Education and Care, we asked the respondents to write down their reasons in the form of free description.

Analysis method

All results were digitized and compared by area. IBM SPSS Statistics Ver.25 was used for statistical analysis. This research study obtained ethical approval from Tokyo University and Graduate School of Social Welfare and was conducted in accordance with its code of ethics (Approval No.: 2018-03).

Results and Discussions

Number of Children in Target Families

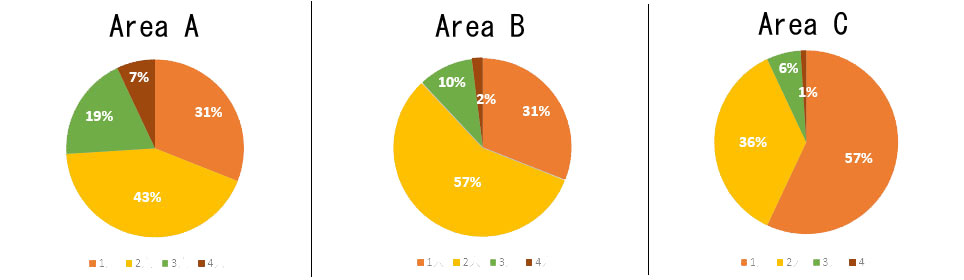

When we compared the number of children in target families by area, there were certain differences, as shown in Figure 1. In Area A, 26% of families have three children or more, the highest rate compared to those in Area B (12%) and Area C (7%). Similarly, families with two children account for 57% of the total respondents in Area B, the highest compared to those in Area A (43%) and Area C (36%). In Area C, families with one child account for 57% of the total respondents and those with two children account for 36% (together, account for 93% of the total respondents).

Comparison Analysis on Three Areas

It is reported that there are significant regional differences in families with children in different areas in terms of mothers' employment status, parents' educational backgrounds, income, etc. as well as parents' perceptions of childrearing (Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute; 2008*14/Suzuki, 2015*15). Based on such data, we conducted a comparison analysis on parents' perceptions of childrearing towards the implementation of Free Preschool Education and Care in three areas.

Area A; This area sees sustained population growth with a high proportion of non-Japanese residents (National Population Census, 2017). The percentage of respondents who are part-time employees is high (Table 1). There is no child on the waiting list for childcare facilities.

Area B: This area has good access to Central Tokyo and has numerous childcare facilities, making it relatively easy to enroll a child in a desired facility. The percentage of respondents who are a full-time housewife is higher than those in the other two areas (Table 1). There is no child on the waiting list for childcare facilities.

Area C: Located in metropolitan Tokyo, the percentage of respondents who are full-time employees is high. For them, taking childcare leave is not difficult (Table 1). There are a large number of children on the waiting list for childcare facilities. It is difficult to enroll a child in a desired facility (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2018).

Timing of Enrollment for the First Child

We started this survey by investigating the actual conditions of enrollment.

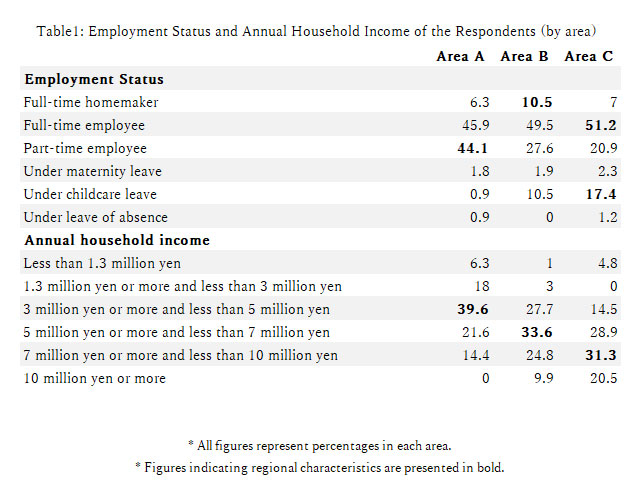

Figure 2 shows the respondents' answers regarding the timing of enrollment in a childcare facility for the first child. In Area C, the percentage of respondents who enrolled in a facility for their child when the child was very young is higher compared to the other two areas. In fact, the percentage of respondents who started leaving the child under six months old at childcare accounts for twice those in the other two areas (Area A: 10%, Area B: 12%, Area C: 21%). In addition, the percentage of respondents in Area C who started leaving the child under one year old at daycare is the highest compared to those in the other two areas (Area A: 32%, Area B: 39%, Area C: 56%).

Meanwhile, in Area A, the respondents who enrolled their children in a childcare facility at the age of four accounted for about 7% of the total, something which was not observed in the other two areas.

Timing of Enrollment for the Second Child

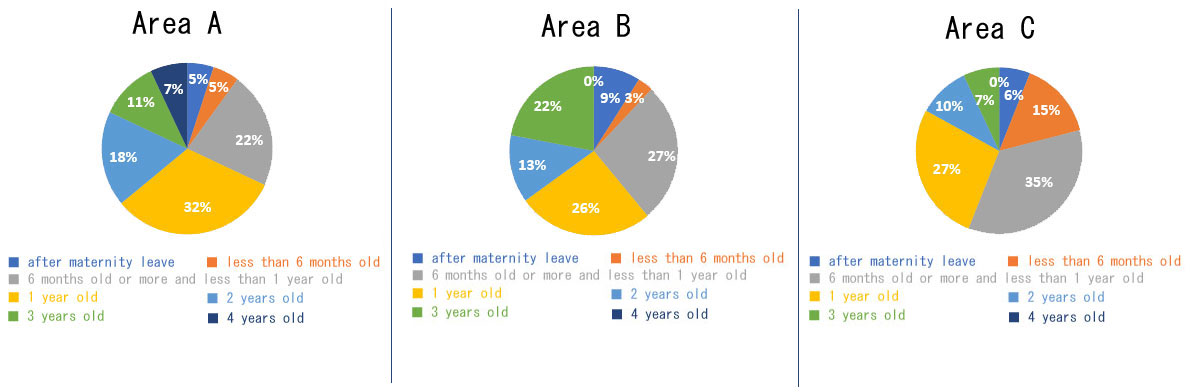

Figure 3 shows the respondents' answers regarding the timing of enrollment in a childcare facility for the second child. In all three areas, the percentage of respondents who enrolled their children in a childcare facility for a second child under one year old is higher compared to those who enrolled the first child under one year old. In Area A and Area C, in particular, the number of the respondents who enrolled their child at the age of six months or more and less than one year increased, while the number of respondents who enrolled their child after maternity leave increased in Area B. In addition, the number of the respondents who enrolled their child at the age of two and three years decreased in Area A and Area B. In particular, the percentage of respondents who enrolled their child at the age of one year is higher in Area B.

(To be continued in Part II)

| | 1 | 2 | |

- *1 "2018 Annual Vital Statistics of Japan (estimate)" by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

- *2 "2017 Vital Statistics of Japan (final data) by prefecture" by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

- *3 "Trend of Total Fertility Rates by Prefecture" by the Cabinet Office.

https://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/data/shusshou.html (in Japanese) - *4 "New Economic Policy Package" by the Cabinet Office.

https://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shinseido/meeting/kodomo_kosodate/k_33/pdf/s2.pdf (in Japanese) - *5 "2018 Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform" by the Cabinet Office.

https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/cabinet/2018/2018_basicpolicies_ja.pdf (in Japanese) - *6 "Summary of Actual Conditions of Daycare Centers (April 1, 2018) and Aggregate Results of the Accelerated Plan for Dissolving Children's Waiting List and the Childrearing Reassurance Plan" by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

- *7 "Childrearing Reassurance Plan" by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2017.

- *8 "Issue of Early Childhood Education: A Need for Education Policies Considering Financial Constraints," Mika Ikemoto, 2018, page 34 of "Reform of Tax and Social Security Systems," The Japan Research Institute, Limited

- *9 "2014 Survey on Marriage and Family Formation" by the Cabinet Office.

- *10 "Parents' perceptions of working style towards the Free Preschool Education and Care: comparison analysis in three areas," Yoko Seki, Futaba Nishiwaki, and Yoshiko Bekki, 2019, from the 72th Poster Exhibition by the Japan Society of Research on Early Childhood Care and Education.

- *11 "Childrearing Support will Save Japan," Haruka Shibata, 2016, page 38, Keiso Shobo

- *12 "Parents' choices for childrearing in metropolitan areas: focusing on the culture of middle-income families," Mariko Ishiguro, 2011, pages 1-15 of the Summary of Doctoral Thesis at Waseda University.

- *13 "How do parents select a childcare facility?" Yoko Seki, 2018a, "Graduate School Research Aid (B)", pages 328-337 of the International Journal of HUMAN CULTURE STUDIES, Institute of Human Culture Studies, Otsuma Women's University; "Parents' perceptions of child rearing through the choice of childcare facilities," Yoko Seki, 2018b, Master's Thesis at Otsuma Women's University.

- *14 "Basic Survey on Childrearing in Japan III (Preschool Children Edition)," Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute, 2008.

- *15 "What regulates the enjoyment of childrearing: focusing on personal and community factors," Tomiko Suzuki, 2015, pages 161-179 of the Participants' 2015 Working Papers on Childrearing Support and Families' Choice, the Secondary Data Analysis Workshop (March 2016).