A MOTHER'S STORY - WHEN THERE'S A SUICIDE

By Monica Vermote

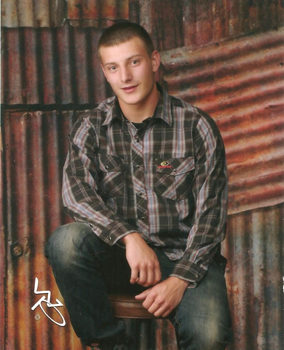

Look at that kid--see anything wrong? Well, I didn't either, but on Saturday, September 19, 2015 two Ohio police officers knocked on my door to tell me my son had committed suicide.

Having seen in the movies how police officers deliver bad news, I was reluctant to let them in, but after acknowledgments, they were admitted and one said, "We're sorry to have to tell you..." I fainted.

When I came to, they told me that Nathan had committed suicide. I thought, "No, not Nathan; he would never do anything like that. They have him confused with someone else." I was alone and they kept asking who they could call to be with me. I wasn't hearing them. My daughter had spent the night with a friend. Trembling I held the phone but couldn't remember how to use it. They took over and left a message on my daughter's phone--she was to come home at once because her brother had committed suicide. Panic set in. "Good Lord, how is she supposed to drive safely after hearing that message." She was hysterical when she arrived, pleading with me to tell her it wasn't true. "No, no, please, not Nathan," she called out over and over. Finally, it dawned on me that my sister could be called.

The officers were trying to tell me what had happened. I couldn't understand; it sounded like a strange language. "Shot himself in the head." That didn't make sense. Nathan didn't have a gun. "Did someone else shoot him?" I asked. They wanted to know about Nathan's girlfriend--wanted her address to see if she was okay. They were afraid it could be a murder-suicide. "Stopppp," I thought. "This can't be happening; my son would not do any of this." I wanted to be with him, needed to, but the officers restrained me from leaving.

My sister, God bless her, showed up; got my physician to prescribe medication to calm me down, helped my daughter, called other people. I was totally useless, crying hysterically and then walking in circles. I felt my chest would explode. I managed to call my mother and Nathan's father, who lives with his wife in Seattle, Washington. The dreadful feeling I had making those calls will probably stay with me until the day I die.

The phone rang. Nathan's boss sounded threatening as she informed me Nathan hadn't shown up for work. "Because he passed away last night," I said. This set off a chain of events involving all of Nathan's friends. Now panic set in. I didn't want anyone to know. There's a stigma that goes with suicide. I knew people would judge us.

My son's friends came over in droves. There must have been a hundred kids at my house, and how sweet they were sharing stories. One girl's story in particular sticks with me. She told me that she was one kid everyone picked on in school, but Nathan walked her to and from classes to prevent that happening. I was stunned hearing this. The guts, the strong character of my son--that told me everything about the child I had raised. I beamed with pride. Those eighteen and nineteen-year-olds knew just what to do. They sat silently at my side as I whaled and cried. They started a "Go Fund Me" and raised money to pay for Nathan's funeral. They put together a car rally, had a balloon release. I was so touched by this love and support that I had to do something to help those kids sort out their feelings, pain and grief. Together with our church pastor, I found an organization to help with individual and group counseling called "Cornerstone of Hope."

In communications with Monica she tells me that she kept questioning why Nathan had ended his life. She paraphrased his suicide note: "He couldn't take the pain and suffering any longer," she said. "He was sorry that he wasn't strong like me, sorry for the pain we would suffer." Yet, Monica said, "He seemed so happy. He had started college and had a job." A doctor in the hospital where she works mentioned that there seems to be a connection between ADHD (Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), depression and suicide. She checked some references and was certain that Nathan was one of the teenagers who had taken his life because of these factors--that had he been told the symptoms, he would have recognized them in himself and asked for help.* ** Though she says she has fabulous support from family and friends, and her son's friends as well, and she is still in counselling, there are days when she doesn't want to get out of bed, doesn't want to be social with anyone, does not want to go on with her life. She said, "What I do need, is to make these feelings stop. I need to be a voice my son never heard." Her message to those who have a child with ADHD and signs of depression is to get help for your child before he/she chooses to end life. If she can spread the message that youth may be more depressed than is realized, if she can prevent another suicide, then Nathan's death will not be in vain.

*Mann, Denise, 2010. "ADHD May be Linked to Depression, Suicide," http://www.webmd.com/add-adhd/childhood-adhd/news/20101004/adhd-may-be-linked-to... (Retrieved 2/24/2017)

**Quote from abstract on Springer's Link of article appearing in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, May 2012, Vol. 40, issue 4, pp 595-606 by Seymour, Karen, Andrea Chronis-Tuscano, Thorhildur Halldorsdottir et al. Emotion Regulation Mediates the Relationship between ADHD and Depressive Symptoms in Youth. "A significant literature suggests that youth diagnosed with Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are at increased risk from later depression relative to youth without ADHD. Youth with co-occurring ADHD and depression experience more serious impairments and worse developmental outcomes than those with either disorder alone, including increased rates of suicidal ideation and suicide completion. ...few studies have examined the mechanism underlying the relationship between ADHD and depression in youth." http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10802-011-9593-4 (Retrieved 2/20/2017)

STAGES OF MOURNING AND SOME SUGESTIONS FOR FRIENDS AND THERAPISTS

- The survivor needs to acknowledge the death, that the death was by suicide, and that a separation is taking place. It helps to talk to a friend and/or a therapist who is a careful listener, supportive, nonjudgmental and comprehends that this is a significant tribulation. In order to accept that this has happened, the survivor needs to talk and talk in specifics about where they were, what they were told, how they responded, etc. Rituals also help to fix the person's acknowledgement.

- The survivor needs to confront and work through the pain. The pain is real, intense, and frightening, but is an expected consequence of the loss. Pain is nature's way of teaching. In this case its purpose is to teach the mourner that they must find another source of love, companionship and sharing. Some mourners hold onto pain because they feel that letting go is disloyal to the loved one; some hold onto the pain as a punishment for some failure they feel guilty about. A therapist can break down components of the person's lack of acknowledging the pain by breaking it down into components and addressing them one by one. For example, if the mourner says that they will miss the companionship of the lost person, the therapist can discuss other times when the mourner had suffered losses of companionship and how it was dealt with.

- The mourner needs to find a meaning for this suicide otherwise a perpetual feeling of anxiety will set in. In life, we have seen that when something happens, there are predictable consequences. When there is no available explanation about the cause of the decision to choose suicide, the mourner feels he cannot trust the world around him. As examples, meaning may come from deciding that you have a message that can help others. They write or give talks about suicide or help organizations that deal with mental health. Lecturer Dr. John Bradshaw said that we give to others what we need to give ourselves.

- Discussions and finding a meaning for the loss is not enough. The mourner needs to express his/her emotions in an acceptable place and perhaps a little at a time. The caregiver can help to overcome the resistance of the mourner to work through his/her feelings which may be fears of pain, of losing control, of guilt, anger or dependency, or in regard to social standards he/she has accepted. Music such as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's "Pathetique" (Symphony No. 6) often precipitates tears and revives memories of the missing loved one. During a recorded movie of an Andre Rieu's Johann Strauss Orchestra, the camera panned the audience of several thousand as Jermaine Jackson (brother of Michael Jackson) sang Charles Chaplin's "Smile," which he performed at his brother's funeral. The camera focused on many men and women in the audience who had uncontrolled tears flowing down their cheeks while the lyrics, written by John Turner and Geoffrey Parsons, urged us to smile even when our hearts are broken and discover that life is worthwhile. Sad movies and stories or pictures of the loved one often generate memories that bring emotional responses.

- "All mourners need to turn away from pain at times to reconnect with the living, growing parts of themselves and others." (1) Restless energy may be directed toward a movie or some creative pursuit such as painting, building a bird house, writing, rowing a boat.

- David Suzuki's TV show, "The Nature of Things," described how scientists have studied what body changes happen when, for example, a person hears something that makes them happy, sad, or angry etc. Researchers find that organs of the body react in automatic ways to a particular emotion. We automatically smile when we feel happy. We automatically gasp when we are surprised, etc. Now they are testing on soldiers suffering from PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) and depression whether this will work in the reverse. If we tell the person to smile and they smile, will they experience the emotions associated with happiness? This tool seems to work.

CONCLUSION

Bereavement after suicide is more complicated than bereavement after death of a loved one by other causes. Survivors often experience many negative feelings, which if not addressed, will persist and influence most areas of their lives for extended periods. The survivors need help to accept the death, work through their pain, discover some meaning that caused the loved one to choose suicide, work through their feelings, and they need help to leave behind their sorrow from time to time by connecting with some uplifting activity. Monica Vermote relates how the trauma of losing her son, Nathan, has changed her life. Science is now uncovering how the body reacts to emotional feelings, and this finding may help those in distress to reprogram their body's reactions to the loss of a loved one by suicide, and aid in their finding meaning and peace of mind.

REFERENCES:

- 1. Rando, Therese A., PhD. 1993. Treatment of Complicated Mourning, Research Press, Champaign, Illinois 61821, 1993. ISBN 0-87822-329-0

- 2. Walker, Ronnie. MS. LCPC. "Suggestions for New Survivors." Alliance of Hope for Suicide Survivors. http://www.allianceofhope.org/alliance-of-hope-for-suic/suggestions-for-new-survivors- if... (Retrieved 2/12/2017)

- 3. "Helping a Friend Who Has Lost a Loved One to Suicide." Suicide Prevention Program, UT (University of Texas) Counseling and Mental Health Center. https://www.cmhc.utexas.edu/bethatone/

friendscopingsuicide.html (Retrieved 2/10/2017)

Marlene Ritchie

Marlene Ritchie