I have once done action research on an environmental configuration that supports children's healthy development of self-expression. This onsite action research aims to identify and solve problems in childcare scenes together with ECEC teachers or assist them in doing so. I was determined to employ this research approach after hearing concerns from a ECEC teacher about Lisa, a three-year-old girl.

The teacher who consulted me had two years of experience at that time. She was worried about Lisa, who only passively looked at and imitated her peers while playing in the "arts and crafts" corner of the nursery room. The teacher did not know what she could do for Lisa. Therefore, I started a discussion with the teacher to find solutions together.

However, it should be noted that this imitating behavior is crucial for the development of children in early childhood. For example, while creating or drawing something, children's imitation intends to "actively collect information, acquire expression images, nurture their own creativity, or overcome the problems . Therefore, imitation should be accepted as a positive skill" (Oku, 2004, p.70).

The teacher was worried about Lisa because she always imitated her peers as if she had no will to decide what to do. She did not look like she really enjoyed her play with things. For example, in the arts and crafts corner, Lisa often smashed her work when she had nearly finished it or tried to hide it if it looked different from her peers' works. However, as the teacher pointed out, Lisa could concentrate on doing something when she knew how to do it and what for. Therefore, the teacher wanted Lisa to be more motivated to actively work on something.

To deal with such a situation, I first made a video recording of Lisa's activities in the arts and crafts corner. It was sometime in March. Twelve children aged four years and eleven children aged five years were mixed in the same nursery room. There were also nine children aged three years, including Lisa, who would enter the four-year-old class in April next month. The size of the nursery room was about forty-two square meters.

On that day, four-year-old children played with clay in the arts and crafts corner. Some three-year-old children, including Lisa, also started playing with clay, probably inspired by these four-year-olds. At the end of the day, the teacher and I watched the videotape, carefully observing the children's activities. As a result, we found some behavioral patterns in Lisa and some issues in the nursery room.

First, Lisa frequently looked at her peers, sometimes for a long time. But, strictly speaking, she was not observing them. Rather, she was distracted by something she heard or saw and spent time confirming what was happening. Because many children of different ages were in that nursery room, the environment did not seem good for her to concentrate on something.

Second, Lisa seemed to be at a loss not knowing what she wanted to do. The teacher and I knew that Lisa could concentrate on her work when she knew how to do it and what for. Therefore, we concluded that the environment in the nursery room did not inspire Lisa's imagination or motivation enough.

Third, we recognized that Lisa could not break the clay into small lumps. The clay was initially prepared for four-year-old children but was too large and stiff for a three-year-old child. As a result, she kept trying to scrape off the clay with a plastic spatula.

After watching the video, we noticed that our approach to providing materials and tools was inappropriate. For example, a large lump of stiff clay was not easy to handle for little children, even though it was given with some plastic spatulas. Based on our observations, we made several hypotheses to formulate an environmental configuration model that would be more appropriate and could be understood as an incentive for Lisa.

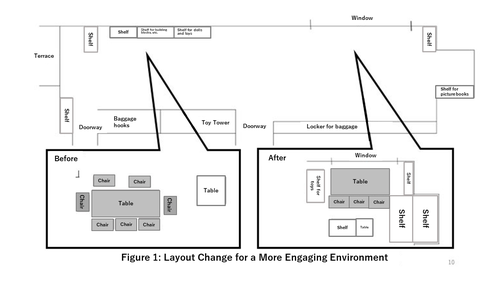

The first hypothesis is that if an environment is created where children with the same activities can be gathered, children will not see other activities and concentrate on their own work. Therefore, the teacher changed the layout of the nursery room. The working table was moved from the center to the wall side, while all chairs were placed to face the wall. In this way, children can concentrate on their own activities and share ideas with their peers sitting next to them.

The second hypothesis is that if an environment is created that inspires and maintains children's imagination and motivation, children like Lisa, who need incentive and vision, can concentrate on their work. To meet this challenge, the teacher placed a large sheet of paper on the floor to let children draw their favorite zoo on it. Next to the paper, we put a clay-working table and several animal figures.

The third hypothesis is that if we create an environment that offers children materials and tools in appropriate conditions and shapes that are easy to handle, children will be more motivated to create something with such materials (e.g., clay). To start, instead of giving white oil clay in the original state. the teacher prepared several small lumps (about 5 cm cubes) of softened clay, which can be handled by three-year-old children. In addition, we intentionally omitted plastic spatulas to let children directly feel the clay and mold something with their hands.

Children playing with clay at the center table

A clay-working table (with no spatula) is separated from other play spaces

Vellum paper with the pictures of children's favorite animals on the floor,

where children play with their handmade clay animals

After we changed the nursery room layout, Lisa's behavior dramatically changed. Now, she does not absent-mindedly spend time looking at other children. Instead, she developed her imaginary zoo world. First, using clay, she created a hippopotamus, which she had observed in a real zoo before. To the teacher's surprise, she then made a place to live in for the hippopotamus, furnished with a bathtub and a lavatory basin. In response to her activities, the teacher drew a zoo house for the hippopotamus with a crayon on a large sheet of paper and made space for her handmade bathtub and lavatory basin. Each time Lisa made something with clay, she excitedly showed her work to the teacher, saying, "Look! This is a bathtub for my hippo!" and "Look, look! My hippo is using the bathroom now!" She repeatedly went back and forth between the clay-working table and her imaginary zoo world on the paper. Because there was no plastic spatula, she used her nails to engrave a pattern on the clay or put her fingers into the clay to make a hole. She accidentally discovered these skills when she was playing with the clay. It looks as if she listens to the voices of clay and responds to such voices in her creative work. Clay, in turn, seems to respond to Lisa's action.

At a reflection meeting, the teacher said, "Some children are immediately inspired by materials and express their ideas using such materials. But Lisa is different. Lisa needs incentive and vision before creating something. Now I understand that we should create an appropriate environment for each child according to their characteristics."

Furthermore, I believe that we also need to create an environment where children can interact with materials and listen to their voices. Clay has its voice as well. Such voices are not phonetic sounds, but represent the materiality, features, and potential mobility of objects; sometimes, these voices can be too soft to be heard.

According to Ms. Fumiko Ito, a Japanese designer and atelierista, listening to the voices of materials is similar to the process of "planning a date" (Ito, 2021).*1 In the dating process, two people, attracted to each other, meet and start chatting to get to know each other to build a romantic relationship, which can be related to the interaction between a child and the material. Therefore, it is essential to create an environment for children not only considering the characteristics of each child but also the interactions between a child and materials. Developing Lisa's positive creativity in playing with clay teaches us the necessity of an environment that supports children in listening to the "unheard voices." In this way, we help children have a deeper dialogue with materials.

- *1 "Atelierista" is a professional artist who interacts with children at childcare facilities practicing the Reggio Emilia approach. In Reggio Emilia in Italy, where the concept originated, an atelierista works at preschools full-time, supporting children's artistic activities.

Cited References

- Fumiko Ito (2021) Kodomo no hyougen to shakai wo tsunagu - Kankyo wo sasaeru atorie zukuri [Creation of an atelier that connects children's expressions and society] Hattatsu, 165, Minerva Shobo.

- Misako Oku (2004) Youji no byouga katei ni okeru mohou no kouka [Effects of imitation through children's drawing processes]. Hoikugaku kenkyu [Research on Early Childhood Care and Education in Japan], 42(2),163-174