Human behavior is influenced by a combination of multiple factors. Therefore, we should avoid thinking that we can understand someone's behavior with just a single causal factor. Nevertheless, humans have limited capacity to handle information and tend to justify things by simple reasoning. Similarly, the subject of this study, i.e., the cause of differences in children's academic performance, has always been and will continue to be a controversial topic. While some maintain this is due to genetic factors, others might cite environmental factors, parents/children's efforts, or the education one received.

In reality, all these factors (as well as other factors not mentioned here) are intricately correlated and influence children's academic performance. We can easily imagine such a mechanism. Yet, we cannot conclude discussion of this topic just by saying "the cause is complex. That is all there is to it." We should not overlook inequality in children's academic performance and devote ourselves to identifying a determinant factor to resolve the issue.

Generally, from the standpoint of scientific practices, we should pursue the truth by appropriately evaluating various complex factors. However, the issue of children's academic performance is different. It does not seem easy to adopt such a scientific approach equitably. Many believe that, like earnings, higher academic performance is better, and excellent accomplishments can be achieved simply by diligent efforts. If a child cannot achieve good academic results, people tend to think that this is because his/her effort is inadequate, his/her study method is wrong, or his/her learning environment is inappropriate. Therefore, people seek for evidence to prove that these factors are truly significant in achieving good results. If they find it, they conclude that only such factors influence children's academic performance.

Given our past failures, we now understand that we should examine every possible or existing factor and include all these factors in our analysis regardless of whether they are favorable for us or not. In addition, we need to assess these factors in a way that enables us to quantify their relative significance. Therefore, in this study, I tried to apply this approach as thoroughly as possible.

Background and purpose of this study

When considering children's academic performance, "family environment" is the factor typically examined first. Nowadays, people often talk about "Parents Lottery(oya-gacha)" (meaning drawing good/bad parents in lottery). We cannot choose or reset our parents no matter how much we desire or hope to be born into a good family. It is like a Gacha-gacha machine (a Japanese vending machine selling capsule toys that are randomly dispensed) or a smartphone game (where a strong/weak skill is randomly assigned to a game character). Most typical environmental factors might be parents' income and academic background, which are collectively called "Socio-Economic Status (SES)." Educational sociologists reported the significant impact of SES on children's academic performance and higher education, showing evidence obtained from mass-data analysis (Akabayashi et al., 2016; Matsuoka, 2019). This development urged people to seek possible solutions for the problem of environmental inequality. For example, we cannot change parents' SES but may reduce its impact through appropriate economic policies.

Parents' SES (Socio-Economic Status) merely creates a starting line for children. There are other parental factors that affect children's academic performance. For example, parental engagement in children's education is also essential, such as providing a suitable learning environment, teaching appropriate disciplines, and so on. Unlike SES factors, parental engagement can be enhanced with some efforts and awareness. For example, suppose a child is born into a wealthy family with parents spending money to spoil him/her. In that case, the family environment is inferior to that of a child born in a low-income family with parents investing their limited money in his/her education.

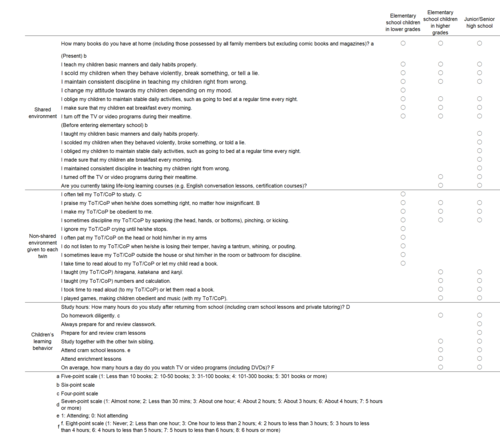

From a children's standpoint, family environments can be divided into direct and indirect factors. Direct environmental factors mean disciplines and education children would receive directly from parents, such as "being told to study" and "being read aloud to from books." In contrast, indirect environmental factors refer to the parents' attitude and the educational engagement children would observe (and indirectly learn) at home, such as "the number of books kept at home" and "life-long learning courses parents are engaged in," and the parental attitude and educational perception they show in their daily lives.

Besides the above direct/indirect factors, children's learning behavior is also one of the direct factors affecting their academic performance. For example, learning behavior includes the length of study hours at home after school and the study habits of doing homework and preparing for and reviewing classwork. Due to the fact that educators and researchers consider earning behavior can improve children's academic performance, their focus and great expectations are placed on this factor.

Next comes genetic factors. It is said that genes determine the intelligence and personality of children. This is the trickiest factor. Some researchers dislike the theory that children inherit their intelligence from parents and strongly object to it. For example, Professor Nisbett, an American social psychologist, wrote his book "Intelligence and How to Get it: Why Schools and Cultures Count" (Nisbett, 2010), arguing that school and home environments are the key determinants of intellectual accomplishment. Likewise, the Japanese social psychologist Kozakai criticizes the gene theory of inheritance and social inequalities in his book "Fabricated Facts called Inequalities" (Kozakai, 2021).

Suppose you are a parent wishing to eliminate the possibility of genetic inheritance before concentrating on your child's education. In that case, the above-mentioned books will greatly encourage you. These researchers strongly insist that the gene theory of inheritance advocated by geneticists is entirely wrong; they consider that environmental influences have a major impact on intelligence and academic achievement.

For this study, I looked into the opinions of behavioral geneticists who argue a hypothetic model differentiating genetic factors from environmental factors. They repeatedly insist that the impact of genetic factors on academic performance is significant (see Loehlin & Nichols, 1976; Lichtenstein & Pedersen, 1997; Chambers, 2000; Asbury & Plomin, 2013).

Of course, there are more factors that may affect children's academic performance. However, in this study, I focus on four main factors identified in the preceding studies. These are: "parents' socioeconomic status," "parental discipline/engagement in education," "children's learning behavior," and "genetic factors." In the past, these four factors have been studied separately, and their significance has been confirmed.

In this study, the point is that these factors are associated with each other. So, for example, the higher the parents' SES, the more books they can afford and the more time they can take to read books aloud for their children. If parents give appropriate discipline, children will study diligently. Furthermore, suppose parents have inherited high intelligence and diligence, have good academic background and income, and genetically tend to give strict discipline, and their children genetically inherit their parents' high intelligence, diligence, and good study habits. In that case, it is highly predictable that children will achieve good academic results. If these causal factors are assumed to be correlated, how should we treat this complexity? In particular, how should we find a way to improve children's academic performance?

The most challenging part is how to comprehend the impact of genetic factors. Genetic factors influence both parents' and children's behavior. Nevertheless, it is impossible to directly ascertain what genetic information is passed on from parents to children. To address this challenge, we have only two methods: to directly examine their genes, otherwise through a behavioral genetics approach (the twin method). This study uses a behavioral genetics approach with the data obtained from our large-scale cross-sectional survey of twins (Ando et al., 2013). The survey was conducted in 2007 as part of the national program "Brain Science and Education," sponsored by the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

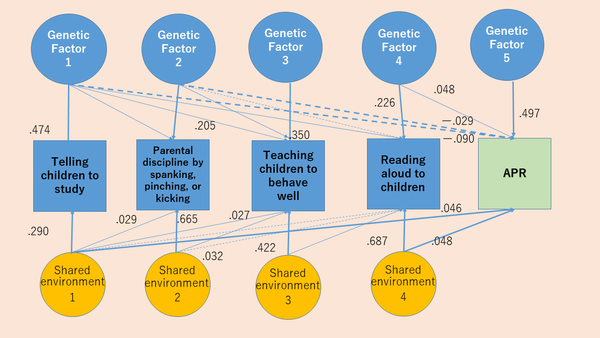

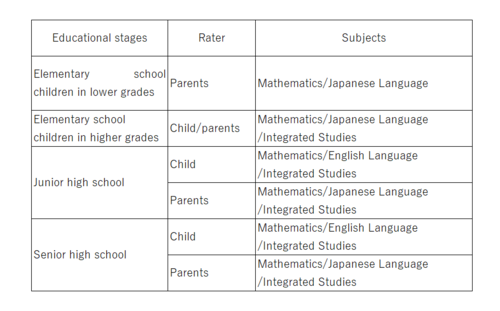

Results: in the case of elementary school children in lower grades

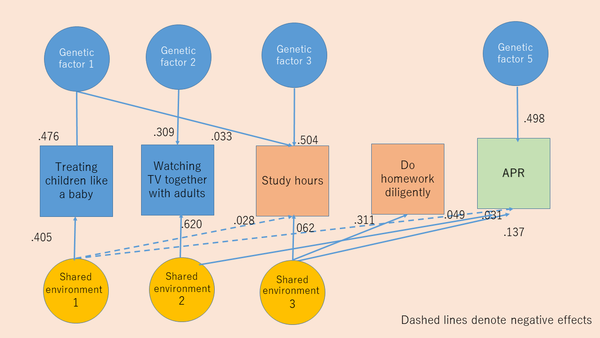

I have discussed this theme in my previous article, "Causal Effects of Family Environments on the Academic Performance of Elementary School Children: Role of Genetic Factors," on the Child Research Net (CRN) website. The previous analysis targeted elementary school children (first, second, and third graders). In this survey, I expanded the scope by targeting children of all school ages from elementary/junior high/high school. Before discussing the results, I will briefly explain the results of the previous analysis on elementary school children in lower grades. Because of their age, children were not able to complete the questionnaire form; therefore, all answers were provided by their parents. For this reason, the children's academic performance rating (hereinafter, "APR") were parental estimations. We obtained answers directly from parents regarding parental discipline and engagement. It was impossible to hear children's opinions regarding their learning behavior. In the end, all answers were obtained from parents based on their subjective standpoint, instead of using objective testing and behavioral assessments. Figure 1 (created by modifying the Figure 7 data in the previous analysis) summarizes such answers.

Note: The impact of non-shared environments (individual environments/differences) was omitted because it affects each of the other variables. Dashed lines denote negative effects. Figures denote contribution ratios. Paths with no figure denote a 0.01 (1%) contribution ratio or lower.

Figure 1 presents a typical behavioral genetics approach, indicating to what extent the variables of parental engagement contribute to children's APR considering genetic factors and shared-environment factors. For example, in the combination of "Telling children to study" and APR (academic results), 47.4% of children's genetic factor relates to the tendency of "Telling children to study." In comparison, 9% of the genetic factor negatively explains APR. In other words, the child's personality causes his/her parents to say, "Study!" The personality is affected by the genetic factor. This genetic factor also negatively affects his/her APR. More precisely, the child genetically inherited a personality of unwillingness to study hard, with the result that his/her parents often tell him/her, "Study!" Interestingly, when looking at "telling the child to study" from the viewpoint of shared environments, the tendency of "telling both twins to study (i.e., shared environment)" is 29%, which increases their APR by 4.6%. In other words, parents who think their child genetically inherited poor APR tend to tell the child, "Study!" more frequently. However, if parents say "Study!" to both twins, their APR tends to be higher. This example indicates that analyzing twin data can clarify the complex relations between genetic and environmental factors.

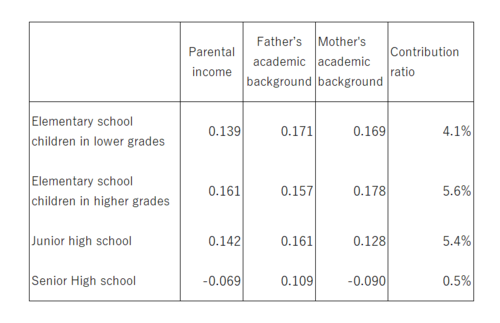

At this point, I will explain some assumptions and considerations not stated in Figure 1. As I mentioned, APR does not refer to academic results measured by actual school testing but refers to academic rating values subjectively assessed by parents. Parents were asked to answer the question "Did your children achieve good academic performance in Mathematics and Japanese Language?" on a four-point scale. The scale consists of four answer choices ranging from "1. Disagree," "2. Somewhat disagree," "3. Somewhat agree," to "4. Agree." The average value of their rating for two subjects were calculated. Then, the effects of children's gender and age, as well as the effects of parental SES factors (so-called "Parents Lottery" elements) were statistically deducted using a multi-regression analysis method. This deduction is based on the purpose of this study: to find a way to improve children's academic performance through parents' and children's efforts, putting aside the "Parents Lottery" elements. In addition, we created Table 5 (see below) showing the effects of parental SES factors on children's APR. In the case of elementary school children in lower grades, these variables account for 4.1% of APR.

We selected the variables of "telling children to study," "spanking, pinching, or kicking," "making children obedient," and "reading books aloud" from the items in Table 1. These items measure parental discipline towards each twin with a five-point scale. We used a multi-regression analysis method to select the variables showing significance. In the case of elementary school children in lower grades, parents who tend to discipline children (ToT/CoP; see Note 2 below) by spanking (the head, hands, or bottoms), pinching, or kicking are more likely to do other parenting practices (e.g., ignoring children crying until they stop, leaving children outside the house or shut them in the room or bathroom for discipline) which I did not mention in Table 1. Because these variables were strongly associated with each other, only the "spanking, pinching, or kicking" variable was selected due to its highest correlation with APR shown in a multi-regression analysis. In this regard, we should think the variables chosen for Table 2 implicitly contain other items of parental practices measured. We could use a factor analysis method to integrate these variables into one variable, such as "tendency to abuse children." However, we decided to maintain the above variables because realistic expressions such as "spanking, pinching, or kicking" can be more comprehensible for parents than abstract expressions such as "tendency to abuse." We would like our readers not to take these variables literally and straightforwardly but to interpret their meaning broadly. For example, "teaching children to behave well" or "reading books aloud" may implicitly include other actions.

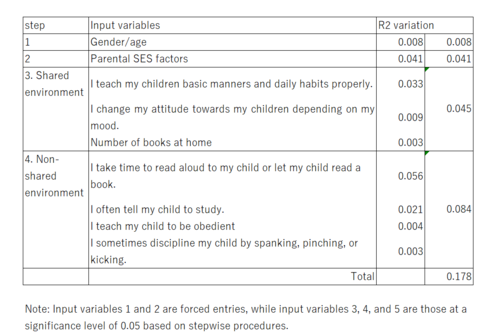

To compound matters, children's APR values are partly affected by parental discipline and other environmental factors given to both twins (i.e., shared environment items in Table 1). Therefore, a multi-regression analysis was conducted to find out significant variables. For example, in the survey of elementary school children in lower grades, the variables of "I teach my children basic manners and daily habits properly," "I change my attitude towards my children depending on my mood," and "the number of books in the house" account for 4.5% of children's APR (see Table 4 below). However, we did not consider this aspect in Figure 1 because it is difficult to compare these variables consistently across elementary, junior high, and senior high school stages.

To review the results across all school stages from elementary to senior high school

Next, I will explain the survey results of all school stages, from elementary to senior high school, in the same way I did for the previous analysis targeting the elementary school children in lower grades (currently published on the CRN website).

Number of sample twins

As mentioned above, this survey was conducted in 2007 as part of the national program "Brain Science and Education" sponsored by the Japan Science and Technology Agency. First, we created a list of about 40,000 pairs of twins sharing the same birth date and address based on the data extracted from the basic resident registers of almost all municipal governments in Tokyo and the three neighboring prefectures of Chiba, Saitama, and Kanagawa. Then, we chose eligible sample families (with children from elementary to senior high school) and sent them a questionnaire survey sheet to them. We obtained their answers anonymously (for more information, please see Ando et al., 2013).

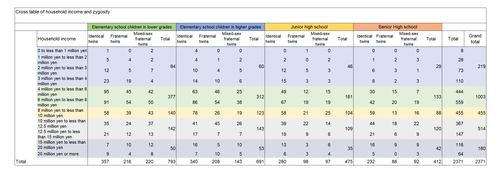

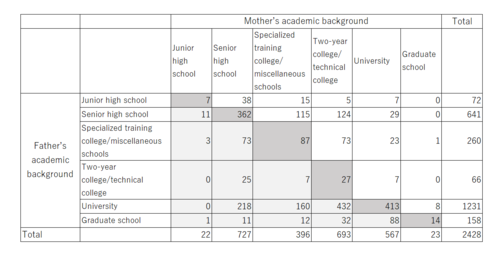

Table 2 shows the basic data of sample families by school stage, household income, and zygosity. The total number of twin pairs is 2371, including 793 pairs of elementary school children in lower grades, 691 pairs of higher graders, 475 pairs of junior high school children, and 412 pairs of senior high school children. Missing values (blank/no-response fields) were omitted from our analysis. Some sample families are not complete twin pairs or parent-child pairs, which we do not go into detail with in this report.

Table 3 shows the breakdown of parental academic background. The number of pairs with the same degree of academic background is relatively high (those cells on the diagonal line from upper left to lower right). Meanwhile, the number of pairs where the father has a better academic background than the mother (those cells below the diagonal line) is higher than the number of pairs where the mother has a better academic background. These trends give us the impression that there are various combinations of couples. It should be noted that the number of sample parents is higher than the number of sample twins because some answers do not contain data about both twins.

As mentioned above, APR does not refer to academic results measured by actual school testing or assessments but refer to academic performance rating assessed by parents and children, respectively. They were asked to answer the question "Achieved good academic performance?" for each subject shown in Table 4, using a four-point scale ranging from "1. Disagree," "2. Somewhat disagree," "3. Somewhat agree," to "4. Agree." As for elementary school children in lower grades, their academic performance was assessed by parents only. The number of subjects was maintained minimum, Japanese/English language, Mathematics, and (for elementary school children in higher grades and above) General Studies. In particular, English Language is a crucial subject for children in junior high school and above and should be included in the questionnaire. For the Japanese Language, we can compare parents' answers regarding children's APR across all school stages, from elementary to senior high school. We analyzed all answers by subject but found no significant difference. Therefore, we used average values.

Due to our questionnaire survey method (by mail), we had no choice but to obtain academic performance ratings from parents and children based on their subjective assessments instead of acquiring the results of actual school testing. The results of national achievement exams would be ideal, but they were not available. We could also have asked parents to copy results from children's school reports. Still, it might have felt burdensome for them to answer the questionnaire if we had done this. Ultimately, we decided to use a four-point scale to get parents' subjective answers. As a result, we received answers from a large number of parents. Therefore, we should bear in mind that their assessments were made in a limited scope, compared with only their neighboring peers, not with all children at school/cram school. I will discuss these limitations and problems later.

As I mentioned repeatedly, this study aims to find a way to improve children's academic performance through parents' and children's efforts, putting aside the "Parents Lottery" elements (i.e., parental SES factors). Table 5 shows the correlation between parental SES factors and APR, including their respective contribution ratios. AThe correlation coefficient is between 0.13 and 0.18 (except for senior high school children). These values are statistically significant but minimal. Their contribution ratio is around 5%, which is relatively low compared to values reported by educational sociologists (20-30%). This result is due to the method of obtaining APR data from the participants' subjective assessments. Therefore, APR data does not accurately reflect the variances of the whole population.

For senior high school children, APR has a slight positive correlation (about 0.1) with "father's academic background", and almost no correlation with "parental income" and "mother's academic background."

Impact of genetic/environmental factors on children's academic performance

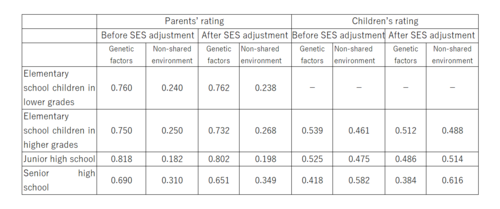

If the impact of parental socioeconomic status (SES) on children's academic performance is significant (although there are certain limitations), to what extent does such parental SES influence the ratios of genetic and environmental factors obtained by behavioral genetics analysis? Table 6 describes the relative contribution of genetic and environmental factors using the twin method before and after adjusting SES variables. As a result, there was no influence found. Suppose the SES variable impacts APR in a shared environment. In that case, a behavioral genetics analysis on APR should have indicated the variables of a shared environment. However, the result is that all differences in children's academic performance are explained by genetic and non-shared environmental factors. In addition, contribution ratios do not show significant variations before and after the adjustment of SES variables. To sum up, 70-80% of parents' ratings were explained by genetic factors, and the remaining 20-30% were explained by non-shared environmental factors (specific to each twin).

For elementary school children in higher grades, we obtained an APR assessed by the children themselves. Genetic factors account for 40-50%, 20-30% below the APR average measured by parents. The reason why the ratio of genetic factors is higher in terms of the APR average measured by parents may be their cognitive bias. They tend to assess the APR for identical twins to the same degree. Therefore, to avoid such bias, we used the APR average assessed by the children for our analysis. For elementary school children in lower grades, we used the average APR assessed by parents in Table 5. To sum up, the results confirmed that about 50% of APR distributions are explained by genetic factors, which is in line with the findings of other researchers in Japan and overseas.

Effects of learning environment provided by parents and children's learning behavior per school stage

Based on the above, I will discuss the effects of the learning environment provided by parents and children's learning behavior on their APR per school stage, putting aside parental SES ("parents Lottery" elements). We used the APR average in this analysis. The effects of parental SES factors on APR were omitted. Similarly, the effects of children's gender and age (inherent conditions children cannot change) were also omitted. These elements are vital parts of the research question, but their effects were minimal in the previous analysis. We conducted a hierarchical multi-regression analysis, setting APR as a dependent (explained) variable and children's learning environment and behavior as explanatory variables.

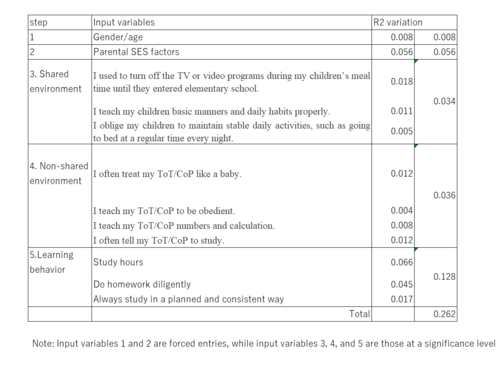

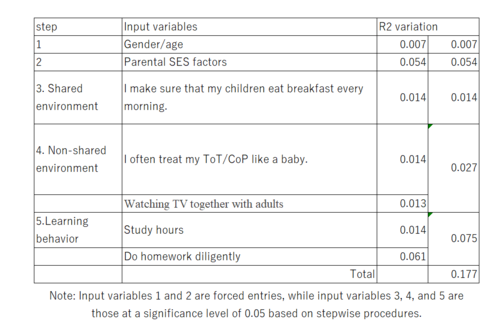

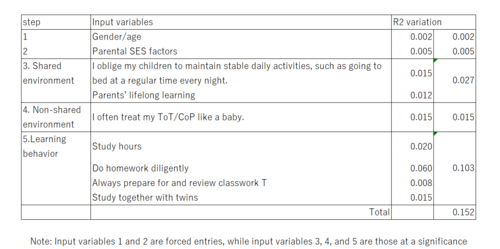

First of all, we calculated the contribution ratio of each variable that explains APR according to their phenotypic level, using a hierarchical multi-regression analysis. The phenotype level means the initial measured value before genetic and environmental factors are separated using a behavioral genetics methodology. Tables 7 to 10 show our analysis results per school stage. As mentioned above, we added children's gender and age (Step 1), and then parental SES factors (SES variables or "Parents Lottery" elements) (Step 2). We omitted these effects, regardless of their statistical significance. Next, we calculated the effects of the shared environment variables shown in Table 1 using the stepwise method and selected those variables with a significance level of 0.05 (Step 3). The stepwise method is a multiple regression analysis method adding a new variable incrementally for significance testing at the 0.05 level until significance is rejected. Then, we added parental engagement in education for each child (Step 4). Finally, we added the variables of children's learning behavior with a significance level of 0.05 using the stepwise method (Step 5). These variables are calculated based on children's own answers (except for elementary school children in lower grades).

Our findings are as follows:

- At all school stages, we confirmed there was higher academic performance among children whose parents are aware and made efforts to give good discipline in a shared environment. "Good discipline" typically means "teaching basic manners and daily habits properly" for elementary school children, "supervising TV viewing and bed-time hours" for elementary school children in higher grades, "supervising regular breakfast" for junior high school children, and "supervising bed-time hours." This indicates that it is necessary to teach children good discipline according to their age. The contribution ratio of such parental discipline accounted for 3-5% of children's academic performance. Therefore, parental discipline in shared environment is significant. This conclusion is in line with the results of other studies by overseas researchers (Hart et al., 2007).

- For children in elementary school (higher grades) or above, parents' attitude of "not treating children like a baby" contributes to higher academic performance at one percent level. This result indicates that such parental attitude may enhance children's autonomy, or children with good academic results may be treated as adults.

- Children's study hours and diligent attitude toward homework contribute to their academic performance at all school stages. Their contribution ratio is 8-10%. Not surprisingly, these variables are the basics of achieving higher academic results.

- As children grow, their learning behavior contributes to their academic performance more effectively than parental engagement. In other words, the younger children are, the stronger are the effects of parents' engagement on children's academic performance.

The effects of non-shared environment and children's learning behavior on APR

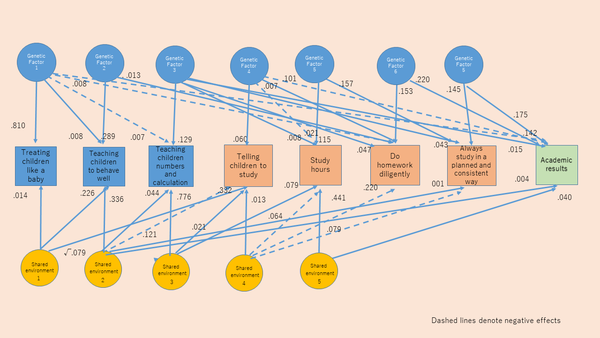

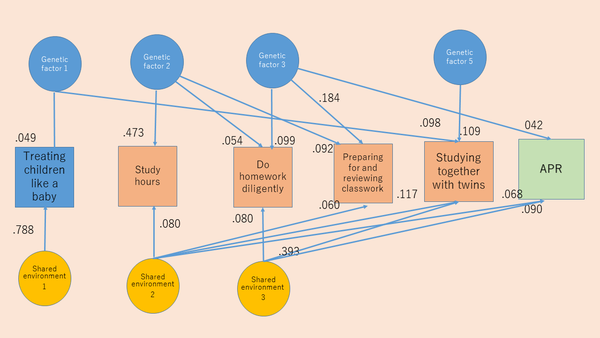

As I mentioned in the analysis results of elementary school children in lower grades, parental engagement in education does not necessarily result from the parental environment but from children's genetic tendencies. Similarly, children's learning behavior is considered to result from their genetic tendency. Still, there may be the effect of family environments as well. Figures 2, 3, and 4 summarize the analysis results regarding children from elementary school children in higher grades to high school, using the same approach as Figure 1.

The structure of genetic and environmental factors seems to be different depending on the children's school stage. For elementary school children in higher grades, a non-shared environment is not entirely provided by parents; it is affected mainly by children's genetic tendencies. In other words, there is an induced correlation between genetic and environmental factors. Meanwhile, children's study hours affect their academic performance through the medium of shared environment. More specifically, whether parents provide a good learning environment for children is a key determinant factor. For junior high school children, parental engagement and children's learning behavior are mainly influenced by a shared environment, showing no association with genetic factors. Therefore, at this stage, it is confirmed that children's academic performance is not affected by genetic factors or is probably affected by other unknown factors.

The results from high school children are somewhat incomprehensible. The contribution ratios shown in Table 6 do not explain the effects of genetic and environmental factors on children's APR. In addition, the impact of genetic factors on children's academic performance is minimal. Instead, the non-additive effects of genetic factors are confirmed, which is unique to this school stage. We assume that using a model specifically designed for additive genetic effects to analyze non-additive variables led to such anomalistic outcomes. Therefore, we cannot say that Figure 4 shows accurate results. This problem needs to be addressed to advance the analysis further.

To sum up, it is confirmed that children's genetic tendencies (e.g., diligently doing homework and preparing for classwork) influence their academic performance. At the same time, the family environment (e.g., making children study and do homework) also contributes to their academic results.

Conclusion

The conclusion of this study is quite typical and simple. Parents should teach children good discipline and avoid treating them like a baby, regardless of parental SES factors and children's genetic disposition. Furthermore, children should study as long as possible and diligently work on homework and preparation/review of classwork, regardless of their genetic disposition. These efforts may improve academic results by a few percent. In addition, according to parents' subjective assessments, parental SES factors do not significantly influence children's academic performance. Therefore, parents do not need to try hard to increase their income nor commit "Education Laundering" (enrolling in a graduate school with a higher level than the graduating university and updating to a higher educational background).

Another point to consider is the children's genetic disposition. Some say this is due to their parents or "Parents Lottery." However, the probability of genetic variation in children born from the same parents is almost equal to that of children born from different parents (Cattell, 1980). This "Genetic Lottery" is as significant as the "Parents Lottery."

Various factors that may bring about the differences in children's academic performance were examined as thoroughly as possible. Then, the relative contribution ratios of these factors were calculated, respectively. As a result, we concluded the above findings, which are not breakthrough discoveries. Nevertheless, we have no choice but to accept these findings and continue pursuing a better way for both parents and children to survive the current education system and school cultures.

Of course, we do not think we can reach an answer easily, because every family needs a different answer depending on children's conditions. However, from the standpoint of a behavioral geneticist, the impact of genetic factors on human abilities is an ever-attractive research inquiry. Like the best-selling novel and TV series "Gekokujou Juken [Grade A Reversal]" (a true story where a very low-rated student works her way up to enter a top-tier junior high school with her parents' earnest support), parents' selfless love and devotion to children in providing good education and learning environment somehow influence children's academic performance. This study proved the effect of such parental engagement, although this only accounts for 5-10% of APR, compared to genetic factors accounting for 50%.

Therefore, children born with poor genetic disposition but who have strong diligence or a good family environment could achieve educational success rather than those with good genetic disposition but no diligence/good family environment. Nobody can predict what will happen. We only say that, from a scientific perspective, if children have no good genetic deposition, the odds of achieving educational success are relatively low. In this regard, what parents and children can do is only to make a calm judgment and prepare themselves for reckless efforts.

Whenever I see such data, I feel let down due to the limitation of the current education system. As a researcher engaged in behavioral genetics and educational psychology, I believe that the findings of this study can be seen not only in school education but also in any other fields. There must be a genetic-environment structure for every human ability, such as communicative, physical, artistic, and empathic abilities. Our world has an unlimited variety of jobs and occupations, and various abilities are exhibited in various business scenes. Even at home, we can see numerous abilities such as cooking, cleaning, washing clothing, doing DIY work, repairing electrical appliances, etc. Furthermore, there may be unknown or undiscovered abilities in our current or future world. For all of these abilities, the existence of genetic disposition is fundamental. Family environments and children's efforts may enhance or diminish the impact of genetic disposition, which increases or decreases the chance of success.

Academic performance often draws individual and social attention due to the current school culture and often triggers chaotic arguments. As a result, academic performance becomes a major challenge for parents and children. However, if we expand the scope of our focus or shift our perspective slightly, we may be able to find other challenges that are more viable and worth trying. Then, we may be able to accept ourselves the way we are, instead of competing with our genetic disposition.

Cited References

- Akabayashi, H., Naoi, M., & Shikishima, C. (2016) Gakuryoku shinri kateikankyou no keizai bunseki --Zenkoku shouchugakusei no tsuiseki chousa kara mietekita mono [An economic analysis of academic ability, non-cognitive ability, and family background: primary findings from a panel survey of Japanese school-age children]. Yuhikaku.

- Asbury, K. & Plomin, R. (2013) G is for Genes: The impact of genetics on education and achievement. Wiley-Blackwell. (translated by Hiroyuki Tsuchiya, Shinyosha)

- Ando, J., Fujisawa, K. Shikishima, C., Hiraishi, K., Nozaki, M., Yamagata, S., Takahashi, Y., Ozaki, K., Suzuki, K., Deno, M., Sasaki, S., Toda, T., Kobayashi, K., and other 24 individuals. (2013) Two cohort and three independent anonymous twin projects at the Keio Twin Research Center (KoTReC). Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16 202-216.

- Cattell, R.B. (1980) The heritability of fluid, gf, and crystallised, gc, intelligence, estimated by a least squares use of the MAVA method. The British Journal of Psychology, 50, 253-265.

- Chambers, M.L. (2000) Academic achievement and IQ: A longitudinal genetic analysis (twin pairs). Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 60(7-B), 3551.

- Hart, S.A., Petrill,S.A., Deater-Deckard, K., & Thompson, L.A. (2007) SES and CHAOS as environmental mediators of cognitive ability: A longitudinal genetic analysis. Intelligence, 35(3), 233-242.

- Kozakai, T. (2021) Kakusa toiu kyokou [Fabricated facts called inequalities]. Chikuma Shinsho.

- Lichtenstein, P., & Pedersen, N. (1997) Does genetic variance for cognitive abilities account for genetic variance in educational achievement and occupational status? A study of twins reared apart and twins reared together. Social Biology, 44, 77-90.

- Loehlin, J.C. & Nichols, J. (1976) Heredity, environment, and personality. University of Texas Press.

- Ando, J. (sv.ed.), Shikishima, C., & Hiraishi, K. (ed.) (2018) Futago kenkyu shirizu1 ninchi nouryoku to gakushu [Twin Study Series 1: Cognitive Skills and Learning]. Sogensha.

- Matsuoka, R. (2019) Kyouiku kakusa kaisou chiiki gakureki [Educational Inequality: Social Hierarchy, Regions, and Academic Backgrounds]. Chikuma Shinsho.

- Nisbett, R. E. (translated by Jun Mizutani in 2010) Intelligence and How to Get it: Why Schools and Cultures Count. Diamond Inc.

Juko Ando

Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Keio University, Ph.D. (Education)

Professor Ando graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Keio University in 1981 and obtained his doctorate degree from the Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University in 1986. He specializes in behavioral genetics, educational psychology, and evolutionary pedagogy, and assumed his current position in 2001. Since 1998, he has been engaged in a large-scale twin cohort study and collected data from more than 10,000 twin pairs, from newborn babies to adults. He is currently conducting longitudinal studies mainly on the effects of genetic and environmental (mainly educational environments) factors on the development of children’s cognitive skills and personality. His publications include “Psychology of genes and environment: introduction to human behavioral genetics” (2014, Baifukan), “Ninety percent of Japanese people do not know the truth of heredity” (2016 & 2017, SB Shinsho), and “Why do humans learn? Thinking of education from biological perspectives” (2018, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho).

Juko Ando

Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Keio University, Ph.D. (Education)

Professor Ando graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Keio University in 1981 and obtained his doctorate degree from the Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University in 1986. He specializes in behavioral genetics, educational psychology, and evolutionary pedagogy, and assumed his current position in 2001. Since 1998, he has been engaged in a large-scale twin cohort study and collected data from more than 10,000 twin pairs, from newborn babies to adults. He is currently conducting longitudinal studies mainly on the effects of genetic and environmental (mainly educational environments) factors on the development of children’s cognitive skills and personality. His publications include “Psychology of genes and environment: introduction to human behavioral genetics” (2014, Baifukan), “Ninety percent of Japanese people do not know the truth of heredity” (2016 & 2017, SB Shinsho), and “Why do humans learn? Thinking of education from biological perspectives” (2018, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho).