Child poverty and educational inequality are critical social issues in Japan.

It is known that parental economic status may limit children's learning opportunities and hence affects their academic performance, educational and career aspirations, and even future earning potential.

According to recent studies in the areas of educational sociology and educational economics, parental academic background and social class significantly restrict children's learning environments and academic performance, which reproduces educational inequality (e.g., Kariya & Shimizu, 2004; Matsuoka, 2019; Nozaki, Higuchi, Nakamuro, & Senoh, 2018; Akabayashi, Naoi, and Shikishima, 2016).

Meanwhile, researchers in behavioral genetics (the study of genetic and environmental influences on individual variations in human behavior) have clarified significant genetic effects on children's intelligence and academic performance (e.g., Loehlin & Nichols, 1976; Lichtenstein & Pedersen, 1997; Chambers, 2000; Asbury & Plomin, 2013).

To clarify this superficial disagreement between the findings of educational sociologists and those of behavioral geneticists, a research survey was conducted targeting elementary school twins. In this survey, data on twins was examined from the standpoint of both educational sociology and behavioral genetics. The survey results confirmed that elementary children's academic performance and learning environments are affected by parental socioeconomic status (i.e., parental income and academic background).

However, these correlation coefficient values (≦1) are not noticeably high, ranging from around 0.12 to 0.24. Therefore, their coefficient of determination (calculated by squaring the correlation coefficient) is not very high either, ranging from 1.4% to 6.0% (mean value: 2.6%).

Next, the twin method was used to identify any other factors affecting children's academic performance and learning environments. Even the effects of family (shared) environments were statistically eliminated from children's academic performance and learning environments, it was concluded that there was no statistical significance. Our findings were presented at the annual conference of the Japanese Society of Child Science two years ago. In fact, about 70% of individual differences in academic performance among children from the same social class are considered to be attributable to genetic factors, rather than family environments. Our article "Social Inequality and Academic Performance: DNA or Environment?" describing these results is now published on the website of Child Research Net.

Studies in behavioral genetics often reveal discouraging facts. For example, suppose it is confirmed that children's individual differences in academic performance are due to various environmental factors in society, such as socioeconomic factors, from the standpoint of educational sociology or educational economics. If so, parents can have hope for their children. As economic inequalities might be resolved by national government policies, social reforms, etc., parents can be motivated to participate in their children's learning experiences, hoping that such inequalities will not hamper the children's success. However, if they are told that children's individual differences in academic performance are genetically derived, they would understandably conclude that there was no hope for them. Behavioral geneticists are somewhat like Darth Vader in Star Wars, a villain from hell smirking at the sword of justice.

I became an education researcher inspired by the words of Shinichi Suzuki, the founder of the Talent Education Research Institute (known throughout the world as the Suzuki Method), which state that "One's ability to speak one's native language is not inborn. As such, all abilities including music are developed through circumstances." I believe that education can save the world and educational sociologists/economists think the same way. Therefore, I seek to find a rational way to save the world scientifically, intelligently, and faithfully. To do so, I try to focus on the entire phenomena, instead of sticking to one's ideology or self-righteous theory based on one-sided aspects of data analysis. Accordingly, this article will discuss my findings, focusing on both aspects of genetic factors and environmental factors.

Survey Purpose and Method

Genetic effects on children's academic performance are significant and non-negligible, even when considering parental economic inequality. This indicates that genetically derived individual variations in academic performance will remain, even if parental economic inequality is entirely resolved by national government policies, etc. In this case, we will be obliged to admit the effects of genetic factors without the excuse of such economic inequality.

However, if genetic effects account for 65% to 70% of children's individual variations in academic performance, and after deducting the factor of parental economic inequality (accounting for a little under 3%) from the remaining 30 to 35%, there still remain unknown environmental factors accounting for about 40% of such differences. This survey aims to clarify these unknown factors.

In this survey, we used data retrieved from our cross-sectional survey under the Tokyo Twin Cohort Project (ToTCoP) as part of the national program "Brain Science and Education" sponsored by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), as was done for the previous survey in 2019. In the previous survey, we conducted analysis on data obtained from elementary school children in both the lower grades and higher grades. In contrast, this survey targets children in the lower grades (from the first to third grades) only, consisting of 784 twin pairs (351 identical twin pairs and 433 fraternal twin pairs)(age range: 7 to 10 years old; average: 8.45 years old; SD = 0.89). The data were obtained from the basic resident registers of almost all municipal governments in Tokyo and the three neighboring prefectures of Chiba, Saitama, and Kanagawa in 2003 and 2004. According to the prescribed procedures, the names and addresses of individuals sharing the same birth date and address were transcribed. As a result, a list of about 40,000 pairs of twins was created, from infants to adults. Then, a questionnaire survey sheet with an explanatory letter and a consent form was sent to the relevant families. The respondents were parents of twins in the third grade or under of elementary school.

We have collected various variables as the factors of family environments. In the previous survey, we analyzed the duration of study hours, including cram school lessons and extracurricular lessons. It was confirmed that these factors contain almost no genetic effects on children's academic performance; therefore, nearly all were considered to be shared environmental factors. In other words, there was no significant difference in similarity between identical twins and fraternal twins. It should be noted, however, that, among children in the higher grades, only 1.8% in terms of study hours, 2.4 % in terms of cram school lessons, and 3.6% in terms of extracurricular lessons are attributed to the effect of parental socioeconomic status (which decreased as shared environment after adjustment using disparity variables).

In the previous survey in 2019, as I explained, we focused on the aspects of methodological discipline that determine children's learning behavior, such as study hours at home and cram school/extracurricular lessons. In this survey, the focus was determined to be on more interpersonal aspects such as parental involvement and practices. These factors can be changed depending on parents' efforts and do not require spending on education such as cram school/extracurricular lessons.

This time, two types of variables were analyzed. Table 1 shows the variables of family learning environments shared by twin pairs, while Table 2 shows the variables of parenting practices towards each twin.

Table 1: Questions regarding family learning environments shared by twin pairs (shared environment)

Fewer than 10 (1); 10 - 50 (2); 51 - 100 (3); 101 - 300 (4); 301 or more (5)

B. Please answer the following questions about your parenting and discipline strategies for your twin children, using the six-point scale.

(1 = "strongly disagree" to 6 = "strongly agree")

1. I teach my children basic manners and daily habits properly.

2. I scold my children when they behave violently, break something, or tell a lie.

3. I maintain consistent discipline in teaching my children right from wrong.

4. I change my attitude towards my children depending on my mood.

5. I oblige my children to maintain stable daily activities, such as going to bed at a regular time every night.

6. I make sure that my children eat breakfast every morning.

7. My partner (spouse) is cooperative in taking care of our children.

8. I turn off the TV or video programs during their meal time.

Table 2: Questions about parenting practices towards each twin

(1 = "disagree" to 4 = "agree")

1. I often tell my child to study.

2. I praise my child when he/she does something right, no matter how insignificant.

3. I ensure my child is well behaved.

4. I sometimes discipline my child by spanking (the head, hands, or bottom), pinching, or kicking.

5. I ignore my child crying until he/she stops.

6. I often pat my child on the head or hold him/her in my arms.

7. I do not listen to my child when he/she is losing his/her temper, having a tantrum, whining, or pouting.

8. I sometimes leave my child outside the house or shut him/her in the room or bathroom for discipline.

9. I take time to read aloud to my child or let my child read a book.

For children's academic performance, we used a mean value of the answers to the question "Did your children achieve good academic performance in Mathematics and Japanese Language?" during the relevant academic year up till March. We asked the respondents to choose from four answer choices ranging from "1. Disagree," "2. Somewhat disagree," "3. Somewhat agree," to "4. Agree," as we did in the previous survey. In addition, we obtained information about parental income and academic background as the indicator of parental socioeconomic status (SES).

In the analysis process, we employed a multiple regression analysis method. First, we calculated scores by deducting the element of parental socioeconomic status (i.e., parental income and academic background; SES) from the element of children's academic performance. This deduction is to measure the effects of parental involvement (directly or indirectly) on children's individual differences in academic performance as factors that are not explained by parental SES. Therefore, we need to eliminate the element of parental SES at the beginning of our analysis.

Next, we examined the degree of significance of each variable relating to children's academic performance as shown in Table 1 (family learning environments shared by twin pairs) and Table 2 (parenting practices towards each twin).

Through this two-step analysis procedure, the variables of parental involvement were selected that substantially affect children's academic performance. Then, the twin method was used to ascertain whether those parenting practices towards each twin affect their academic performance as one of the environmental factors or as a result of responding to their genetic capacity (or induced by such capacity).

Results

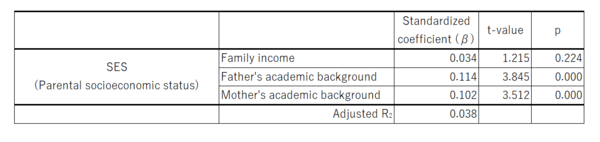

Before examining the effects of parental involvement and practices, we first conducted a multiple regression analysis on the effects of parental socioeconomic status (SES) as required by educational sociologists and educational economists. Table 3 shows the results of our study.

Table 3: Effects of parental socioeconomic status (SES) on children's academic performance (by multiple regression analysis)

These results indicate that there is no statistical significance in the variable of family income, while the variables of father's and mother's academic background have a certain significance. Therefore, 3.8% of children's individual differences in academic performance are attributed to the aggregated effects of these three variables.

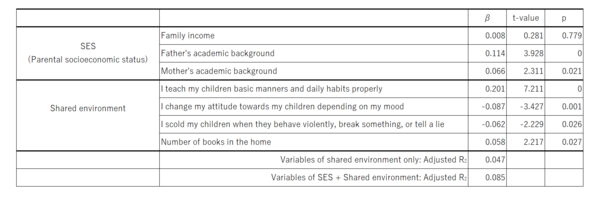

After deducting the effects of these SES variables, we conducted a stepwise multiple regression analysis to analyze the factors of family learning environments shared by twin pairs (i.e., shared environment; Table 1), which are deemed to have statistical significance. The stepwise multiple regression method is a forward selection method adding a new variable incrementally for significance testing until significance is rejected. Table 4 shows the results of our stepwise multiple regression analysis.

Table 4: Effects of parental socioeconomic status (SES) and family learning environments shared by twin pairs (shared environment) on children's academic performance (by multiple regression analysis)

Looking at Table 1, the variables that have statistical significance include "I teach my children basic manners and daily habits properly," "I change my attitude towards my children depending on my mood (because the score is negative, which means "I do not change my attitude towards my children depending on my mood"), "I scold my children when they behave violently, break something, or tell a lie (this score is also negative, which means "I do not scold") and the number of books in the home. These results indicate that the respondent parents interact with children consistently and maintain appropriate discipline strategies such as scolding children when they behave badly. In addition, the number of books in the home is also an important factor. These four variables account for 4.7% of children's individual differences in academic performance. Together with the coefficient of determination for the variables of parental SES (3.8%), the total coefficient of determination becomes 8.5%.

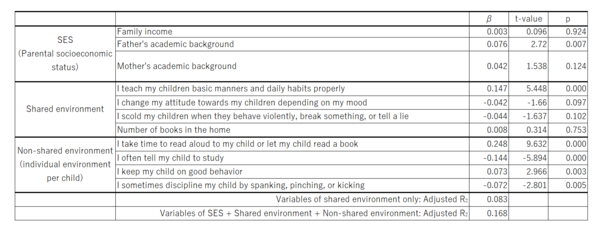

Then, what else will have an effect on children's individual differences in academic performance, apart from the variables of parental socioeconomic status (SES) and shared environment? Is there any variable that significantly affects children's learning through parental involvement in each twin's education? We conducted a multiple regression analysis again for the variables shown in Table 2, and the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Effects of parental socioeconomic status (SES) and shared/non-shared environment on children's academic performance (by multiple regression analysis)

Looking at Table 5, the variables that have significance include "I often tell my child to study" (the score is negative, which means "I do not tell"), "I ensure my child is well behaved," "I sometimes discipline my child by spanking, pinching, or kicking" (the score is also negative, which means "I do not"), accounting for 8.3%. As a result, the total coefficient of determination for these explanatory variables becomes 16.8%.

It is important to be aware that these parenting practices may affect children's academic performance. This suggests that effective discipline strategies can contribute to children's better learning.

In this regard, however, behavioral geneticists raise another question. The gist of their argument is as follows: parents read aloud to their children not because they understand this practice will enhance children's academic skills, but because they know children have a higher genetic capacity for acquiring academic skills. That is why they do not have to tell children to study often. Furthermore, parents do not resort to physical punishment, such as spanking and pinching, because children have a higher genetic capacity for learning discipline.

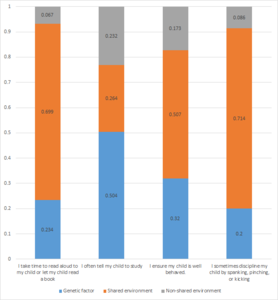

Therefore, we analyzed these "environmental" variables using the twin method, calculating the relative proportions of genetic, shared environment, and non-shared environment variables. If the proportion of non-shared environment variables is greater, this means that parents discipline each twin regardless of their genetic capacity. Likewise, if the proportion of shared environment variables is greater, this also means that parents discipline both twin pairs regardless of their genetic capacity. In other words, these are purely the effects of environmental factors, not genetic factors. In contrast, if the proportion of genetic variables is greater, this means children's learning environments are developed in response to their genetic capacity.

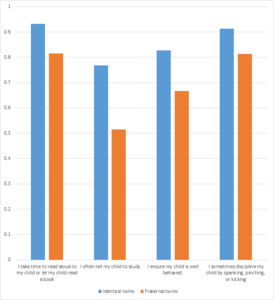

Figures 1 and 2 below indicate the results of our analysis using the twin method. Figure 1 shows similarity between identical twins and fraternal twins regarding these four variables, using correlation coefficients. Figure 2 shows the relative proportion of each genetic, shared environment, and non-shared environment variable with the calculation based on the above correlation coefficients.

Looking at Figure 1, the similarity of fraternal twins is as high as the similarity of identical twins in all variables. These results suggest that the same degree of parenting practices are provided for both twins. Nevertheless, identical twins are more likely to experience similar environmental factors than fraternal twins, indicating that children's genetic capacity induces these environmental factors. This phenomenon is called the "evocative (reactive) correlation" between genetic and environment.

Click image to enlarge

|

Click image to enlarge

|

|

| Figure 1: Correlation of twins in non-shared environment that affects their academic performance | Figure 2: Relative proportions of genetics and environmental factors contributing to non-shared environment that affects their academic performance |

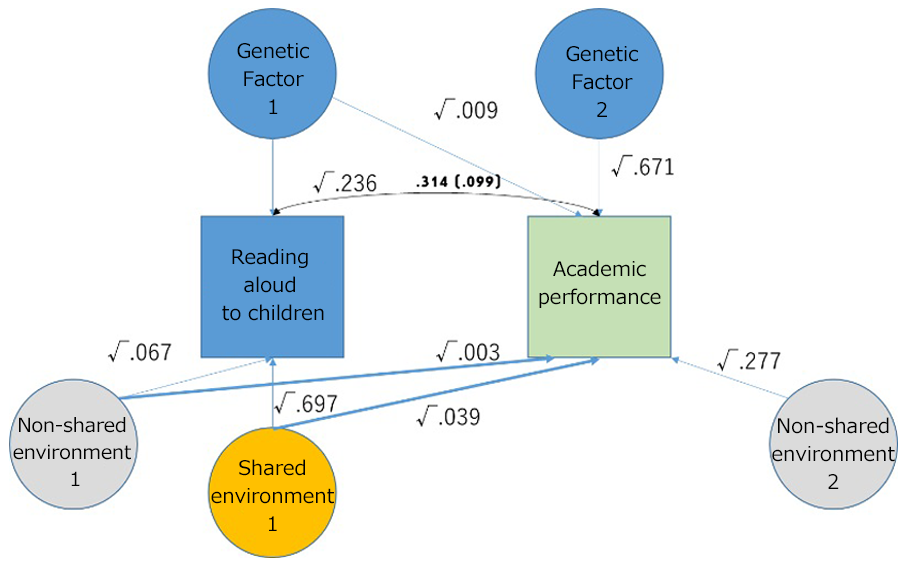

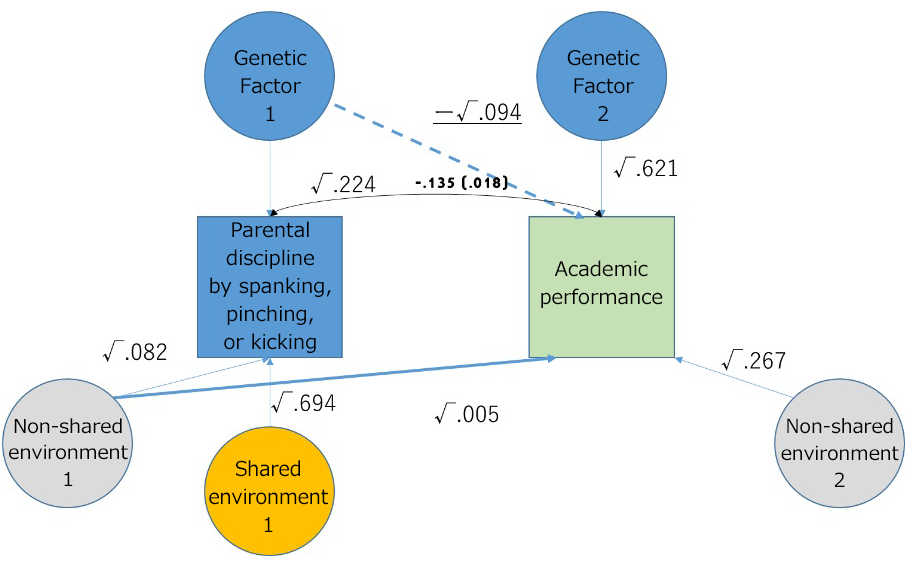

Furthermore, a bivariate genetic analysis was conducted using the twin method to investigate whether the effects of parenting practices towards each twin on their academic performance are solely derived from environmental factors or induced by their genetic capacity. First, we focused on the effect of "reading aloud to children" on their academic performance. I will explain here how to interpret the results shown in Figure 3.

Data in the square frames represent the question item and the answer's score (or combined score), which are deemed as actual data obtained (observed variables). There is a correlation (0.314) between "reading aloud to children" and "academic performance." This value represents 9.9% of children's individual differences in academic performance. We need to examine the proportions of genetic, shared environment, and non-shared environment variables that result in such a correlation. Therefore, we conducted a bivariate genetic analysis. The analysis results are shown as arrows (paths) starting from each variable in the circle. Figure 3 shows only data that have been identified to have statistical significance.

In the case of Figure 3, the effect of genetic factor (Genetic Factor 1) relating to the practice of reading aloud to children on their academic performance is 0.009 or 0.9% (Generally, a coefficient of determination is obtained by squaring the value of this path factor: therefore, the calculated value is expressed in the form of a square root. The total of these calculated values obtained from each observed variable should be 100%). This indicates the existence of an induced correlation between genetic and environment. In other words, parents are willing to read aloud to children because their academic performance is genetically higher. In addition, the factor of "Shared Environment 1" relating to the practice of reading aloud to children is 3.9%, while the factor of "Non-Shared Environment 1" is 0.3%. These results indicated the possibility of a greater effect of environmental factors than genetic factors (although the total of these values is 5.1%, well below the estimated value of 9.9% by our correlation analysis, such a discrepancy is often generated due to different analysis methods. Please understand it in this way: the effect of reading aloud to children accounts for about 5% to 10% of children's individual differences in academic performance).

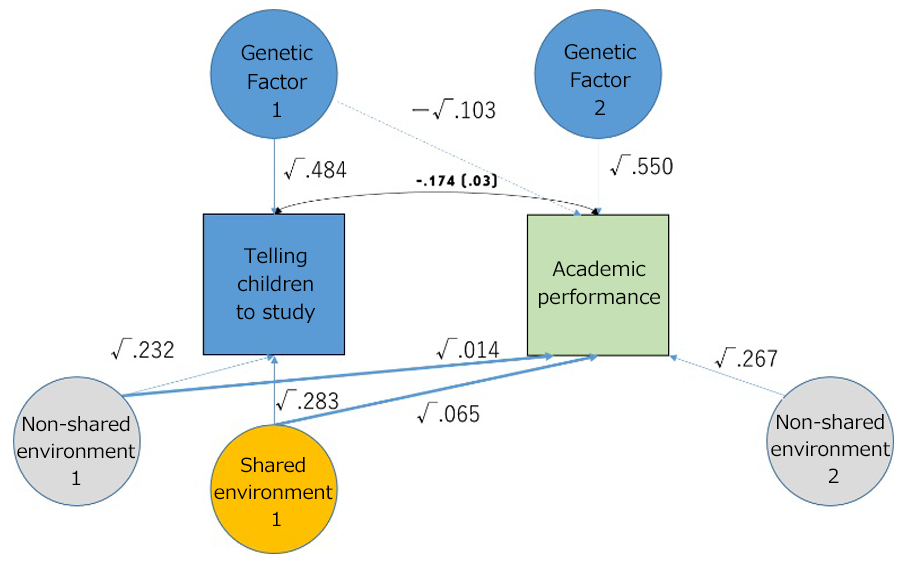

Next, I will explain Figure 4. Figure 4 indicates the analysis results regarding the effect of "telling children to study" on their academic performance. There is a negative correlation (-0.174) between them. The coefficient of determination is 3%, which is not very high. These figures indicate that the practice of "not telling children to study" positively affects their academic performance. This may sound paradoxical, but the fact is, parents of children with good academic performance are more likely to avoid telling them to study. Our bivariate genetic analysis revealed that the negative correlation is a result of genetic factors. Parents of children with genetically good academic performance are more likely to avoid telling them to study because of their genetic capacity. This accounts for 10%. More interestingly, the environmental variables suggest a positive correlation, contrary to the genetic variables. Environmental variables indicate 6.5%, while non-shared environmental variables indicate 1.4%. The parenting practice of telling children to study positively affects children's academic skills. The contribution ratio of this environmental variable is 8%.

Therefore, the total contribution ratio of both genetic and environmental variables is 2%, close to the value of 3% calculated by the above correlation analysis. In general, parents of children with good academic performance are more likely to avoid telling them to study. However, when closely examining such children with the same genetic level, it is obvious that the practice of telling children to study can enhance children's academic performance.

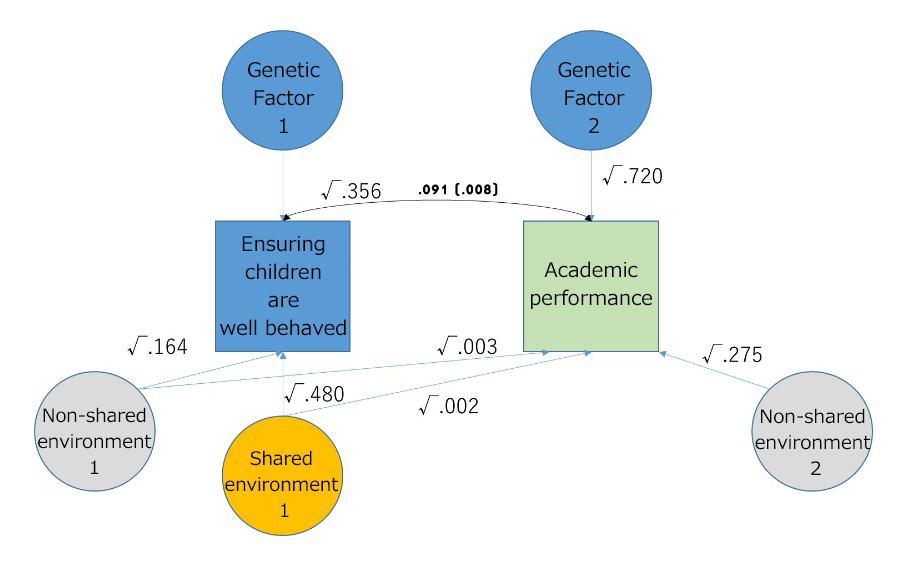

Figure 5 shows the effect of "ensuring children are well behaved" on their academic performance. The coefficient of determination is less than 1%. This result does not involve genetic variables but the variables of shared environment (0.2%) and non-shared environment (0.3%). Although the effectiveness of such parenting practice is minimal, its importance should not be ignored.

Finally, Figure 6 shows the effect of "parental discipline by spanking, pinching, or kicking children" on their academic performance. As with the practice of "telling children to study," parents of children with good academic performance seem more likely to avoid such forms of discipline. The coefficient of determination is 1.8%, mostly attributed to their genetic capacity.

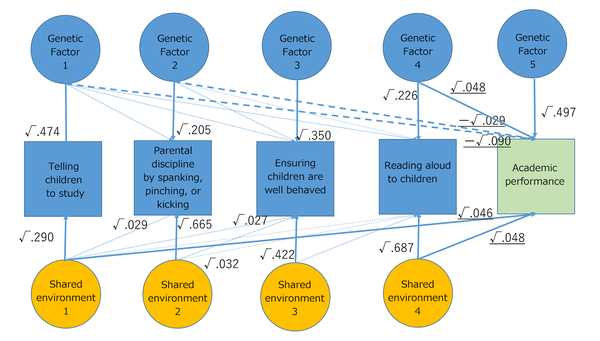

So far, I have explained the correlations of genetic and environmental variables that induce the positive effects of parental involvement and practices towards each twin on their academic performance. Finally, we aggregated and summarized these items of analysis data (apart from the data of non-shared environment, which is omitted due to its complexity) and created Figure 7 below. Underlined paths represent significant correlations between each non-shared environment variable and children's academic performance.

Figure 7 consists of the summaries of each analysis. It is confirmed that children's genetic capacity induces specific "parenting practices" such as "reading aloud to children," "not telling children to study," and "parental discipline without spanking, pinching, or kicking." In addition, parenting practices such as "telling children to study" and "reading aloud to children" can enhance children's academic performance. Their contribution ratios are immaterial, ranging from 3 to 5%. About 50% of children's individual differences in academic performance are due to genetic factors, while about 10% are due to shared environmental factors ("telling children to study" and "reading aloud to children"). The remaining 40% are due to non-shared environmental factors.

In addition, the variables of non-shared environment (i.e., individual environment specific to each twin in the same household) contribute to 26-27% of children's individual differences in academic performance (not shown in Figure 7 but shown in Figures 3 to 6). Therefore, about 13-14% out of the remaining 40% are due to parenting practices towards each twin.

Conclusion

In the previous study, we reported survey results that supported the perspective of behavioral geneticists. These results could be disappointing for parents because children's academic performance might be significantly affected by genetic factors. In this survey, however, we tried to find out if there was any possibility to "save the world," "solve the social issue of educational inequality," and "enhance children's academic performance" by way of environmental factors, based on the same twins data used in the previous survey.

As a result, it is revealed that about 70% of children's individual differences in academic performance are due to genetic factors. Only about 5% are purely attributed to parenting practices of "telling children to study" and "reading aloud to children," respectively, as the factors of shared environment. In addition, about 15% are attributed to the factors of non-shared environment, that is, parenting practices towards each child. In sum, we confirmed that about 70% of children's individual differences in academic performance are due to genetic factors, while about 20% are attributed to the environment where parents are willing to make efforts in parenting for each child. Is this conclusion pessimistic?

From the standpoint of behavioral geneticists, it is rather surprising that a certain significant correlation is confirmed between specific environmental factors (parenting practices) and children's academic performance. As past studies in behavioral genetics provide only the abstract statistical contributions of genetic and environmental factors, there was no specific implication for future actions. In particular, the effect of reading aloud to children, one of the environmental factors, on children's academic performance is more significant than that of genetic factors. Likewise, the effect of ensuring children are well behaved is mainly induced by environmental factors, not by genetic factors.

It should be noted, however, that these results do not guarantee children's success. For example, even if you buy a lot of books for your child ("the number of books in the home" is significant as one of the shared family environments for twins), strictly discipline him/her, and make him/her study hard, it is still uncertain whether your child will be accepted into a famous university. We should not forget about the contribution ratio of genetic factors, which is still high, at 50%.

Nevertheless, parents can definitely expect their children to achieve better academic performance to some extent, by providing good parenting practices suitable for their children, without spending a lot of money on cram school/extracurricular lessons (regarding books, you can buy them secondhand or borrow from a library). At this point, we should not consider that the ultimate goal of education means only achieving good academic performance.

It is true that if children can achieve good academic performance at school, they will have more chances to be accepted into a famous school and gain employment with a famous company. Therefore, it is quite understandable that parents raising an ordinary child desire that s/he achieve better academic performance as much as possible, even if the child has no extraordinary talent like Yuzuru Hanyu (Olympic champion figure skater) or Sota Fujii (young professional shogi player). They cannot stop expecting their child to be accepted into a top-ranked university, wishing for the help of a legendary super teacher like Mr. Sakuragi in "Dragon Zakura" (a Japanese manga series set in a high school) or Mr. Tsubota in "Flying Colors (Biri gyaru)" (a Japanese film about a high school girl). However, at the same time, parents should realize that achieving better academic performance at school is not the sole goal in their life. Each child can have a respective path to success, and parents should provide educational opportunities to help the child choose a suitable path.

I believe that the results of our survey will provide some insight for parents who wish that their children will achieve success. This survey focuses only on children's academic performance. It is confirmed that about 50% of children's individual differences in academic performance are attributed to genetic factors. In other words, each child will commence his or her educational journey from a different starting point, respectively. Parenting practices can affect or accelerate the progress of their journey to some extent.

For children who are not genetically good at learning at school, it may be difficult for them to achieve outstanding accomplishments during their school life. However, as a behavioral geneticist and educator, I believe that parenting practices suitable to such children, reflecting their genetic capacity, can help them discover their potential and develop various abilities other than academic skills. Young children cannot clearly demonstrate their genetic capacity because of their unstable behavior and emotional movements observed in their daily life. However, according to recent studies in behavioral genetics (e.g., Briley & Tucker-Drob, 2014; Tucker-Drob & Briley, 2014), children's genetic capacity will be fixed during late childhood to young adulthood.

Going forward, we need to find a way to understand the effects of genetic factors and provide education leveraging such effects, instead of looking for a way to overcome the barrier of genetic factors. Some researchers in behavioral genetics (e.g., Ando, Shikishima, and Hiraishi, 2021) are currently conducting such studies with their unique methodologies.

References

- • Akabayashi, H., Naoi, M., & Shikishima, C. (2016) An economic analysis of academic ability, non-cognitive ability, and family background: primary findings from a panel survey of Japanese school-age children. Yuhikaku.

- • Asbury, K. & Plomin, R. (2013) G is for Genes: The impact of genetics on education and achievement. Wiley-Blackwell.

- • Ando, J. (sv.ed.), Shikishima, C., & Hiraishi, K. (ed.) (2018) Twin Study Series 1: Cognitive Skills and Learning. Sogensha.

- • Briley, D. A., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2014). Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1303-1331. doi:10.1037/a0037091

- • Chambers, M.L. (2000) Academic achievement and IQ: A longitudinal genetic analysis (twin pairs). Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 60(7-B), 3551.

- • Kariya, T., & Shimizu, K. (ed.) (2004) Sociology of academic achievement: changes of academic achievement and problems of learning shown by surveys. Iwanami Shoten.

- • Lichtenstein, P., & Pedersen, N. (1997) Does genetic variance for cognitive abilities account for genetic variance in educational achievement and occupational status? A study of twins reared apart and twins reared together. Social Biology, 44, 77-90.

- • Loehlin, J.C. & Nichols, J. (1976) Heredity, environment, and personality. University of Texas Press.

- • Matsuoka, R. (2019) Educational Inequality: Social Hierarchy, Regions, and Academic Backgrounds. Chikuma Shinsho.

- • Nozaki, K., Higuchi, Y., Nakamuro, M., & Senoh, W. (2018) Causal effects of parental income and family environments on children's academic performance: Considering the outcome of international comparative analysis. NIER Discussion Paper Series No.008.

- • Tucker-Drob, E. M. and Briley, D.A. (2014) Continuity of genetic and environmental influences on cognition across the life span: A meta-analysis of longitudinal twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 140(4), 949-979.

Juko Ando

Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Keio University, Ph.D. (Education)

Professor Ando graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Keio University in 1981 and obtained his doctorate degree from the Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University in 1986. He specializes in behavioral genetics, educational psychology, and evolutionary pedagogy, and assumed his current position in 2001. Since 1998, he has been engaged in a large-scale twin cohort study and collected data from more than 10,000 twin pairs, from newborn babies to adults. He is currently conducting longitudinal studies mainly on the effects of genetic and environmental (mainly educational environments) factors on the development of children’s cognitive skills and personality. His publications include “Psychology of genes and environment: introduction to human behavioral genetics” (2014, Baifukan), “Ninety percent of Japanese people do not know the truth of heredity” (2016 & 2017, SB Shinsho), and “Why do humans learn? Thinking of education from biological perspectives” (2018, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho).

Juko Ando

Professor at the Faculty of Letters, Keio University, Ph.D. (Education)

Professor Ando graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Keio University in 1981 and obtained his doctorate degree from the Graduate School of Human Relations, Keio University in 1986. He specializes in behavioral genetics, educational psychology, and evolutionary pedagogy, and assumed his current position in 2001. Since 1998, he has been engaged in a large-scale twin cohort study and collected data from more than 10,000 twin pairs, from newborn babies to adults. He is currently conducting longitudinal studies mainly on the effects of genetic and environmental (mainly educational environments) factors on the development of children’s cognitive skills and personality. His publications include “Psychology of genes and environment: introduction to human behavioral genetics” (2014, Baifukan), “Ninety percent of Japanese people do not know the truth of heredity” (2016 & 2017, SB Shinsho), and “Why do humans learn? Thinking of education from biological perspectives” (2018, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho).