3. Research objective

There have been many articles written on the development of web-based virtual pets; yet very little has been written about how people feel toward their virtual pet and how virtual pets influence people. Some studies have been made, such as one conducted by T. Chesney & S. Lawson (2008) on the impact of nintendogs. This is a study of a software-based virtual pet, and its effect on humans, in which the researchers insist that having a virtual pet has emotional effects, helping to raise self-esteem. Another approach by E. L. Altschuler (2007) is the use of a virtual pet as used by a child with autism in an attempt to find a linkage that enables the child to make contact with the real world.

Therefore, the purpose of this article is to conduct research focusing on university students to examine how they feel about web-based virtual pets, and what kind of effects a virtual pet would have after making conversation with it.

Within this research, we will seek to find an answer to questions in relation to what type of virtual pet students prefer from among the four types mentioned; whether students are attached to their virtual pet or not; whether a virtual pet can be a comfort to them or not, etc. in order to explore possibilities of the relationship between humans and virtual pets as well as to find ways to use virtual pets in the field of education.

4. Research method

4-1 Research Item

I conducted a questionnaire on the following items to 128 students of University Y and University W, after having them chat with their pets. Students kept a record each day when they had conversation. Then students replied to questions at the end. Even if they had a pet, they were not obliged to play with it. Given around a month, students were to chat with pets for about a week in total.

(1) Daily Record

Students were asked to make a record on the following items when they made conversation with their pet:

- Start time __:__

- Feeling before conversation

Answer in number among ten stages from "(1) very depressed" to "(10) very refreshed". - Record of conversation (Paste here)

- Feeling after conversation: same items as ii

- Finish time __:__

- Feeling about pet

Students were asked to choose from six stages: from "(6) like very much" to "(1) dislike very much" - How many times a week on the average did you chat with your pet? ( ) times

- Students were asked to choose from six stages: from "think so very much" to "don't think so at all" on the following items.

- - My pet is a companion.

- - Keeping a pet gives me something to care for.

- - My pet makes me experience pleasant activities.

- - My pet is the source of stability in my life.

- - My pet makes me feel myself needed.

- - My pet gives me pleasure and laughter.

- - Keeping a pet gives me something to love.

- - Touching my pet comforts me.

- - I am happy to see my pet.

- - My pet makes me feel loved.

- - My pet makes me feel trusted.

- Impressions of several virtual pets

Students were asked to choose from six stages: from "think so very much (6)" to "don't think so at all (1)" on the following items.- - 'I receive comfort from my pet while chatting with it (Types of virtual pets are not particularly specified)'

- - Mouse-driven type (named "nyanta", which reacts to mouse's movements for patting, feeding, etc., but does not chat)

nyanta is likable.

nyanta elicits attachment.

nyanta gives comfort. - - Virtual pet randomly reading blog entries (named "wanta", which reads the content of blog and murmurs aloud. It moves according to movements of the mouse.)

wanta is likable.

wanta elicits attachment.

wanta gives comfort. - - Virtual pet using memorized dialogues (named "hikotama", which never fails to answer when spoken to. Its reaction is only speaking with no movement driven by mouse.)

hikotama is likable.

hikotama elicits attachment.

hikotama gives comfort. - - Virtual pet chatting and playing with an avatar (his/her alter ego) (named freely by a user)

A pet in splume is likable.

A pet in splume elicits attachment.

A pet in splume gives comfort.

- What do you expect from a virtual pet?

- - conversation: yes no

- - be able to control the pet's movements with the mouse cursor:

yes no - - be able to express feelings and ideas through the avatar (alter ego) together with the pet: yes no

| (1) | Changes in feelings between start time and finish time of conversation with a virtual pet

|

| (2) | Frequency of conversation Setting a low frequency conversation group (5 times or less) and a highly frequency conversation group (6 times or more), favorability of pets and comfort between the frequencies of conversation are compared. |

| (3) | Impressions of several virtual pets Results of the answers in six scales on four types of virtual pets (the mouse-driven type, the type randomly reading blog entries, the type using memorized dialogues, and the type talking and playing with an avatar) based on three responses: 'I have a favorable feeling towards my pet,' 'I feel an attachment towards my pet' and 'I receive comfort from my pet' are compared. |

| (4) | Expectation of virtual pets Responses ('yes' or 'no') to following three questions on what they expected of their pet are compared:

|

| (5) | Dialogues A text-mining approach using "Trend Search" software to analyze the words exchanged between them is conducted. It is a way to parse words and recognize keywords, which appear frequently, as nodes and shows the relevance between the nodes appearing most frequently linking with other words in distances. |

5. Results

(1) Changes in mood before and after making conversation with a virtual pet

a. Gender differences

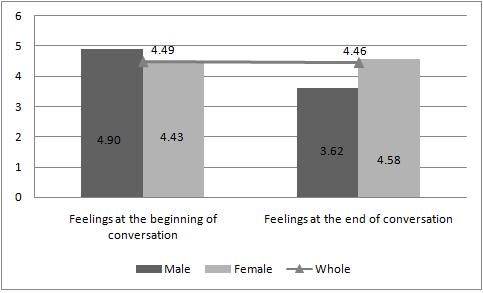

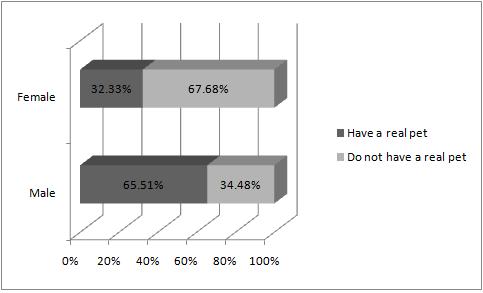

I have conducted the variance analysis to see if there is any gender gap in the feelings of companionship before and after making conversation with a virtual pet. The result shows that there is no change in the feelings as a whole (without distinction of sex); however, Figure 5 shows that there is a certain gender gap in the feelings at the beginning (F(1)=4.26, p<.05) and ending of conversation (F(1)=11.41, p<.01): male students report higher feelings of companionship than female students at the beginning of the study, but by its completion, the level of attachment reported by males drops below that recorded for female students. Further, Figure 6 shows the breakdown of the existence of real pets, indicating that more male students have a real pet than female students do (X2(1)=10.31, p<.01 ). This may be one of the reasons why the feeling of companionship among male students resulted finally in a lower score, since the male student who has a real pet might have expected as much companionship from a virtual pet as he received from the real one, but such an expectation did not materialize.

Figure 5. Changes in Mood by Gender (Average Scores)

Figure 6. Breakdown of Existence of Real Pets

b. Conversation time with a virtual pet

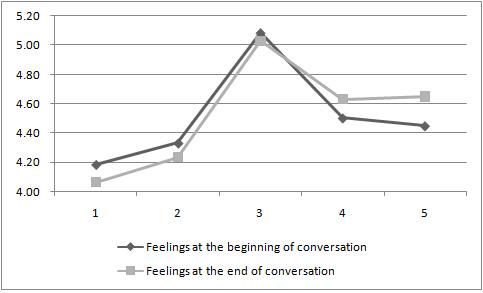

Next, I have conducted the variance analysis to see if the length of conversation time with a virtual pet has an effect on the person's mood over the duration of the communication. Figure 7 shows that the difference in the feelings of companionship between the beginning (F(4)=4.58, p<.01) and the end of the conversation (F(4)=3.56, p<.01) is dependent on the length of conversation time.

Figure 7. Changes in Mood by Conversation Time (Average Scores)

(2) Frequency of conversation

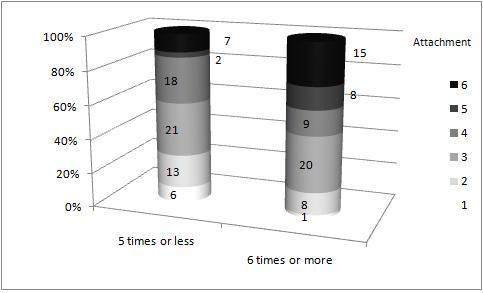

In observing relationships between the frequency of conversation and the degree of attachment to a virtual pet, I have used a chi-square test. As a result, a highly frequent conversation group (6 times or more) indicates a stronger favorability rating, and a low frequent conversation group (5 times or less) weaker favorability rating (X2(5)=14.045, p<.05; Figure 8).

Figure 8. Frequency of Conversation and Degree of Attachment to Virtual Pets

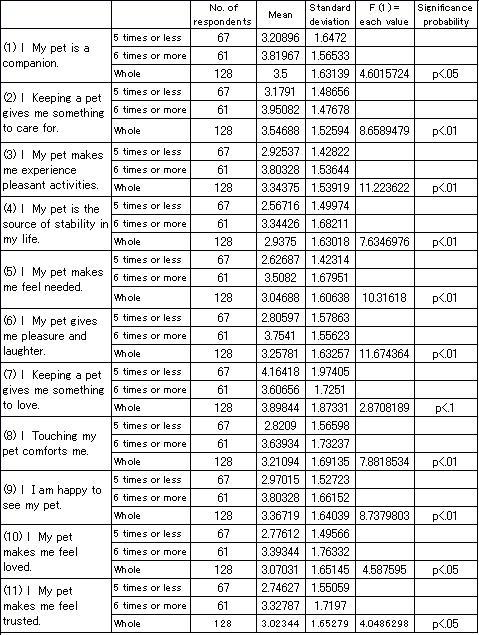

Another result of variance analysis is shown in Table 1: this records the results in relation to the frequency of conversation with a virtual pet and the degree of comfort from it. There is a significant difference in average scores of each group; the high frequency conversation group (6 times or more) rated higher scores for all questions except for question (7), for which the low frequency conversation group (5 times or less) rated a slightly higher score.

Table 1. Relationship between Frequency of Conversation and Degree of Comfort

(3) Impressions of the virtual pets

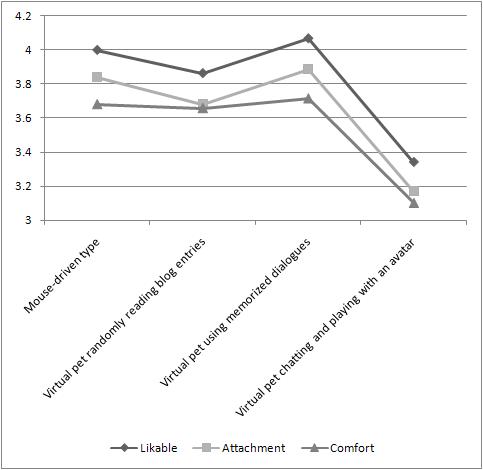

Figure 9 shows the result from the study in relation to how students feel about each type of virtual pet, with the average scores obtained from their answers.

Students were asked to rate their impression on a scale of one to six based on three responses: 'I have a favorable feeling towards my pet,' 'I feel an attachment towards my pet' and 'I receive comfort from my pet'. These comments refer to all four types of virtual pets (the mouse-driven type, the type randomly reading blog entries, the type using memorized dialogues, and the type talking and playing with an avatar). As a result, there is no significant difference in the scores for the first three types: however, the scores in all three questionnaires for the type talking and playing with an avatar are relatively lower for than other types.

In addition, through the variance analysis of scores for the questionnaire 'I receive comfort from my pet while chatting (Types of virtual pets are not particularly specified),' no significant differences were found by gender or by existence of a real pet (n.s.).

Figure 9. Impression of Virtual Pets

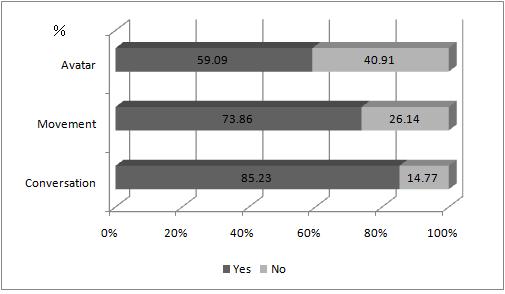

(4) Expectation of virtual pets

Next, I conducted a survey on what expectation students have of their virtual pet. I asked the students to respond 'yes' or 'no' to three statements regarding whether they expect to:

- - engage in a conversation with their pet

- - be able to control the pet's movement with the mouse cursor

- - be able to express feelings and ideas through an avatar (alter ego) together with the pet.

The result in Figure 10 shows that 85 percent expect a virtual pet to have a conversational function; on the contrary, however, 41 percent do not expect it to function with an avatar.

Figure 10. Expectation of Virtual Pets

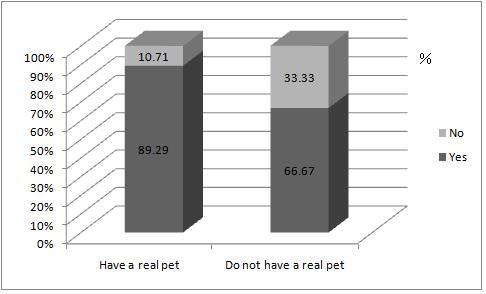

With a chi-square test, I have studied the relationship between the 'gender gap' and the individual factors of conversation, mobility and the avatar. Likewise, I considered these three factors in relationship to the 'existence of a real pet.' As a result, there is a significance in the relation between the question 'Do you expect to be able to control the pet's movement with the mouse cursor?' and the 'existence of a real pet' (X2(1)=5.06, p<.05). Also, the result in Figure 11 indicates that students who have a real pet expect more mobility of a virtual pet than those who do not have a real one. Other combinations by gender or the existence of a real pet do not show any significant difference (n.s.).

Figure 11. Relationship between Mobility and Existence of Real Pets

(5) Dialogues

While conducting this survey, I noticed that some students felt uplifted after making conversation with a virtual pet, while others felt down; therefore, I have compared samples of each dialogue.

Studying these samples, it became evident that a critical factor in the responses is whether the students were successful in establishing interpersonal communication with their virtual pet during conversation. The dialogues shown in the sample below demonstrate that when students felt down, there is a gap in their conversation with their pet, since the pet is entirely unable to respond with the words the owner wanted to hear. In contrast, in dialogues where students felt uplifted, there is good communication, and furthermore, the pet can give its owner some comforting words such as 'Welcome home, my dear master,' a phrase that might come from an elegantly dressed maid in a cafe, where the maids treat their customers as masters.

The speech generated by the virtual pet is extracted automatically from the corpus programmed and stored into the database according to the situation given: the speech does not come from a voluntary behavior of such a digital pet. If the pet owner speaks to his/her pet with a phrase, and if this is within the scope of programmed dialogues, then the conversation will be established. However, if such a phrase has never been stored in the database, the virtual pet would not express any expected response, and the conversation becomes incoherent.

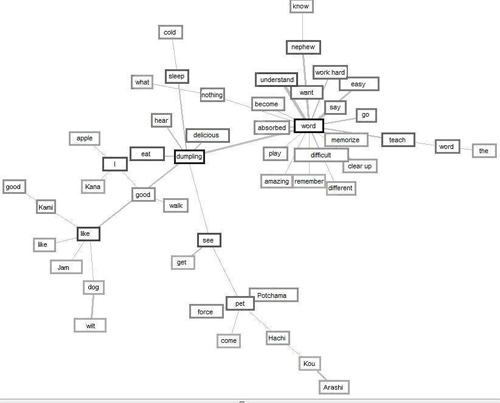

Figure 12. Node Analysis of Dialogues

For further understanding of the communication between the pet owner and the virtual pet, I have carried out a text-mining approach using "Trend Search" software to analyze the words exchanged between them. The result of such mapping is shown in Figure 12. The color density of each frame surrounding a node represents the word frequency. The stronger the color of the frame the more frequently the node in that frame appears linked with other words.

This software program extracted three main keywords: 'word,' 'dumpling,' and 'like.' Among them, the 'word' is most frequently connected with other keywords, as shown in the phrase, for example, 'I don't understand the word. Please say it again with another simple word.' Thus, this keyword appears many times in the speech of the pet, indicating that the pet is asking its owner the meaning of 'word' again and again during conversation. It is quite understandable why the pet owners experienced frustration with their virtual pet.