Review of the First Survey

1) Survey respondent details

In the first survey, we received 58 responses from among the readers of our Japanese website (with 10 comments), and 16 responses from those of the Chinese website (with one comment) as of August 19, 2013. It was a good start. We would like to express our gratitude to all those respondents. This feature on our English website also started on September 6, so we are looking forward to receiving more comments from different nationalities.

In this report, we aim to discuss the following: (1) results of a similar survey obtained from university students from Japan, China and Korea; (2) summary of responses obtained from the readers of our Japanese and Chinese websites (as of August 19); (3) summary of comments obtained from those readers. And lastly, we will request your comment on these results.

Notes:

In the survey of university students from Japan, China and Korea, we received support from professor Kotaro Takagi at Aoyama Gakuin University. The survey was conducted in his class of cross-cultural understanding.

For the responses obtained online, it is difficult to determine that the quantitative data of the survey reflects average opinions across the country due to the nature of the online survey. We hope the data can be used as reference for other similar surveys.

Those comments obtained from the readers may be considered as effective qualitative data, although it is difficult to obtain sufficient information of the readers' attributes in this survey. Therefore, the discussion is based on the qualitative data of the minority group. For further information on the methodology for cultural discussions based on such data, please refer to "Intrinsic ambiguity and substance of cultures: identifying a culture from the perspective of differential cultural psychology" (vol. 12, Qualitative Psychology, 2013 in Japanese) or "How Can We Study Interactions Mediated by Money as a Cultural Tool: From the Perspectives of 'Cultural Psychology of Differences' as a Dialogical Method" (in the Oxford Handbook of Culture and Psychology, 2012) by the author and his colleagues of this article.

2) Results of a similar survey obtained from university students from Japan, China and Korea

The following script was used in the first survey.

University student C and E are close friends. C's tuition fee was due the next day, but his/her parents had not yet sent the money. Borrowing the money from somebody was the only solution that C could think of. After worrying a great deal, C decided to borrow money from close friend E.

Q1: If I were C, I would... 1. Never borrow money from E. 2. Do the same as C did.

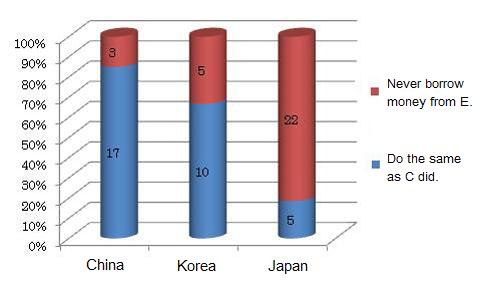

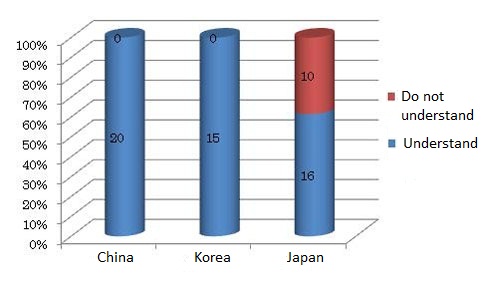

The figure 1 below summarizes the answers to Q1 from university students from Japan, China, and Korea.

Figure 1: Summary of answers to Q1 (respondents: university students from Japan, China and Korea)

As you can see, a considerable majority of Japanese university students answered that they would never borrow money from friends. This result is very similar to that derived from another research study on "M and C (Money and Children)," which was jointly conducted with researchers from Japan, China, Korea and Viet Nam. In sum, most Japanese students, compared to those in China and Korea, think carefully or negatively about borrowing money, especially when the amount of money is large.

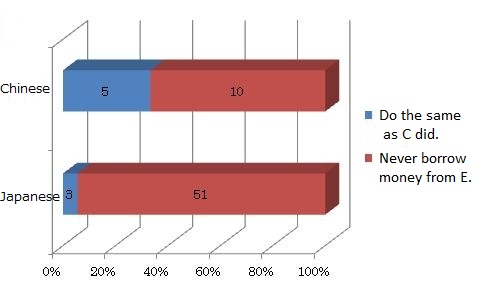

Then, how about the responses from the online survey? The figure 2 shows the summary of responses obtained from the readers of our Japanese and Chinese websites.

1. Never borrow money from E. 2. Do the same as C did.

Figure 2: Summary of answers to Q1 (respondents: readers of Japanese and Chinese websites)

The age composition of the respondents is as follows:

| Age | Japanese website | Chinese website |

| 20's | 9 | 5 |

| 30's | 18 | 5 |

| 40's | 16 | 3 |

| 50's | 10 | 0 |

| 60's and above | 1 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 |

As you can see, a wide age range of readers from the Japanese website responded to our survey, and their answers are similar or more negative in comparison to those from the Japanese university students. Meanwhile, the readers of the Chinese website who responded to the survey are fewer, their age ranging only from their 20's to 40's. Therefore, it is difficult to provide a concrete conclusion regarding Chinese respondents, but it seems that more adult readers replied "I would never borrow money from E" compared to the university students.

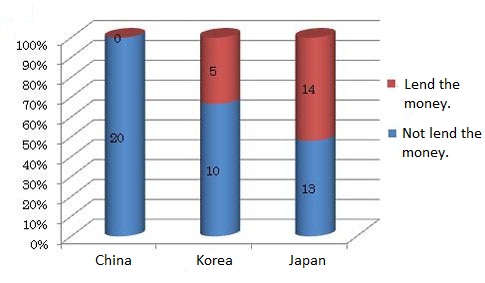

Q2: If I were E, I would... 1. Lend the money 2. Not lend the money

Figure 3: Summary of answers to Q2 (respondents: university students from Japan, China and Korea)

For Question 2, the number of respondents who replied "I would never lend the money" increases in the order of China, Korea and Japan. The difference is remarkable, in particular, whereby all of the Chinese respondents replied "I would lend the money" whereas only half of the Japanese respondents replied in the affirmative.

It is interesting to note that, in comparison to the answers to Q1, there are some respondents of both Japanese and Chinese university students who answered "If I were C, I would never borrow money from E" but answered "If I were E, I would lend the money." It seems that most Chinese university students tend to think "I should lend money if my friend asks me." Japanese students would probably think "I don't want to borrow money from friends, but I might feel I should lend money if asked."

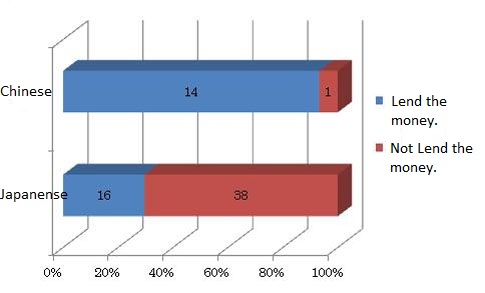

Next, Figure 4 shows the answers to Q2 obtained from our online readers.

Figure 4: Summary of answers to Q2 (respondents: readers of Japanese and Chinese websites)

Interestingly, many readers of the Chinese website who are older than the university students replied "I would lend the money" while the readers of the Japanese website gave more "harsh" responses, "I would not lend the money." Note that, in case of Q1, more adult Chinese respondents replied "I would never borrow money from E" compared to the Chinese university students, but in case of Q2, they replied "I would lend the money" at the same rate as the students. In contrast, most adult Japanese respondents replied "I would never borrow money from E," as did the Japanese university students (this is partly due to a "ceiling effect"), but more adults replied "I would never lend the money" compared to the students.

These results indicate that adult respondents in Japan and China, the generations who have to make a living on their own (different from university students who are dependent on their parents) are more realistic and sensible regarding economic matters, therefore, they think differently when considering whether to borrow or to lend money depending on their culture.

Q3: About C's decision, I... 1. Understand 2. Do not understand

Figure 5: Summary of answers to Q3 (respondents: university students from Japan, China and Korea)

Summarizing answers to Q3 is somehow not so easy, as the word "understand" in this question can be interpreted in many different ways, such as "Borrowing money is not good, but I can understand why C had to do so," or "Borrowing money is acceptable," or more positively, "Borrowing money is a normal habit."

Nevertheless, we can see a significant difference between answers from Japanese university students and those of Chinese and Korean students, as Figure 5 shows. The majority of Japanese students responded without question that "I cannot understand C's behavior," while no one among Korean and Chinese students replied with the same answer (although it is difficult to know what they mean by word "understand"). This indicates that the majority of students in Korea and China consider C's behavior as normal, or at least, it is likely to happen in their daily life.

Next, we look into the answers obtained online.

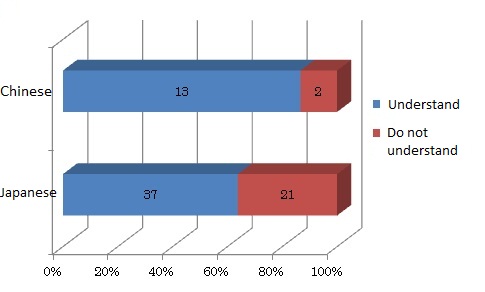

Figure 6: Summary of answers to Q3 (respondents: readers of Japanese and Chinese websites)

Figure 6 indicates the same tendency among Japanese website readers in their responses to Q3 as those of the Japanese university students. In contrast, some Chinese website readers aged 20 or above replied "I cannot understand C's behavior" while no Chinese student replied in this way. It is difficult to guess why there is a slight disparity in answers between Chinese website readers and students. Some reasons worth considering are: C's behavior is acceptable for university students but not for adults in China, or because they are students of high-standard universities in Beijing that led to their willingness to lend money. Subsequently, we determined that this matter is not a concern as the disparity is relatively small.

3) Online comments

For the first survey, we received 11 comments from Japanese and Chinese readers. The comment given on the Chinese website was written in Japanese, and it seems that the person who gave the comment had received compulsory education in Japan or is a Japanese businessman stationed in China (we omitted such a response when aggregating the entire data).

In the end, we did not receive any comments from those who are clearly identified as Chinese. This is probably because we did not make enough questions to identify respondents' attributes, or because we did not disclose the data of Japanese respondents as this was the first survey.

Therefore, in this report, we will briefly introduce comments from the Japanese website readers only. We have the impression that the readers quite enjoyed this survey, and some people even suggested further questions. We are looking forward to receiving responses from other readers of different nationalities such as China after reading these comments.

Comments:

(1) C should first consult his/her parents or university tutor.

(2) The value of money may change depending on one's personality and financial situation.

(3) I'm surprised by the survey results as I always thought that Chinese people are strict about borrowing and lending money. Maybe they answered "yes" because this is a matter of tuition fees. I don't want to lend money to my friend because I'm afraid this may destroy our friendship. Maybe Chinese people think the opposite, they lend money to maintain a good relationship in the future. We should learn from Chinese students who have strength in achieving their objective.

(4) Once I was asked the same thing by a foreign student from Asia. I declined his request as he could not provide me with a practical plan to repay the money. Students in China and Korea think positively about borrowing money because they are too young to worry about secured repayment. I think one option to resolve C's problem is first checking the financial condition of C's parents, and then, consulting the university office together with C.

(5) I wonder if there is very little trouble regarding money matters in China and Korea.

(6) In Japan, we often say "Don't lend money to your friend otherwise you will lose a friendship." I also heard that the meaning of "thank you" in Japanese and Chinese is different. This may cause misunderstanding between each other. Chinese people always try to help families and close friends on any occasion. For Japanese, gratitude is mutual. We try to help people in trouble even though they are not close friends. But when helping a close friend, it is implicitly understood that the person helped should do something in return in the future. It may be interesting to look into the difference in using "thank you" in Japanese, Chinese and Korean society.

(7) I always want to maintain an emotional relationship with friends without involving money matters. I think students in China and Korea are tough as they can broaden a network of relationships through money.

(8) I'm surprised at the difference between young people's way of thinking about friendship in Japan and other countries. Maybe they cannot say "no" when asked by a close friend, or they are afraid of destroying the friendship if they say "no." I think the survey results might have been different if there had been the option of "think together." It is not good for students to easily borrow or lend money to someone, as they are still dependent on their parents. They should think more seriously about money as well as parents who pay their tuition fee. This survey caused me to reflect on these matters and I look forward to reading the results of the next report.

Note: Your feedback may be published on this series. If you do not wish to disclose your personal information, please state this request clearly in your feedback. Please acknowledge that you transfer copyright of your feedback to CRN when sending it to us.