4. Developmental process of relation-adjusting ability and cultural differences

Then, how can we nurture such "relation-adjusting ability"? To address this question, apart from this survey, I will refer to some insights from my research on the development of children's social skills from the perspective of cultural developmental psychology.

When children are aged one, they actively play with and often fight over toys with other children. However, their behavior gradually begins to change at around one-and-a-half years old, and when they become two-year-olds, they fight less frequently over toys. Instead, they start negotiating with their peers, saying, "Please lend it to me" or "Let's take turns." Moreover, when they become three-year-olds, they understand that suddenly grabbing a toy away from another child is "bad." If they do so, this means they are teasing, intentionally attacking, or bullying the child.

Then, why do such changes happen?

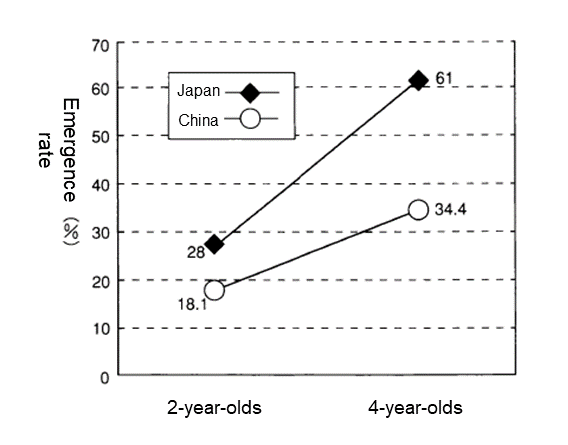

By comparing the same behavior of children in China (Beijing), we see an interesting phenomenon. When Chinese children become two-year-olds, they start showing sufficient "negotiating" skills. However, they are more likely to suddenly grab a toy away from another child rather than negotiate with the child. This difference between Japanese and Chinese children is apparent, which we can clearly and statistically confirm based on survey data. Simply put, Japanese children tend to "ask first and get the toy," while Chinese children tend to "get the toy first" (Yamamoto 1997, 2004, etc.).

It would appear to many that "Japanese children behave politely and peacefully" and "Chinese children are aggressive, living by the law of the jungle." However, this is not true.

If children live by the law of the jungle, a strong child would always seize a toy from other peers when they are fighting over the toy. We can observe this phenomenon in a troop of wild chimpanzees or Japanese monkeys. This social structure is called a "dominance hierarchy," where stronger animals behave dominantly.

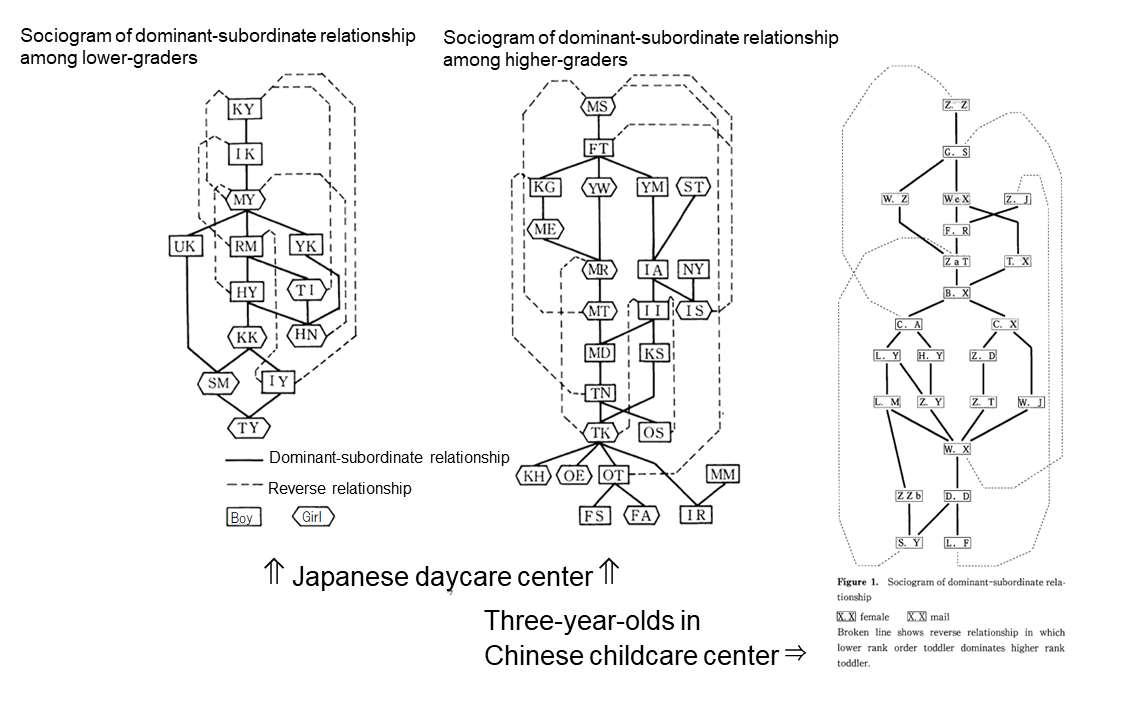

However, according to the survey data, we cannot identify such a dominance hierarchy among Japanese and Chinese children. For example, we sometimes observed Child A seizing a toy from others or Child B seizing a toy, or sometimes, Child A and B behaved submissively to another child (Yamamoto 1991, 1997, 2006, etc.). Figure 9 below shows the sociograms of dominant-subordinate relationships among children based on the survey data from childcare facilities in Japan and China. These sociograms rank children in order of the number of seizing a toy from others. The solid line indicates a dominant-subordinate relationship. However, there are also reverse cases (dotted lines) where a lower-rank child dominates over a higher-rank child.

For example, a three-year-old Japanese girl called MS would take toys from other children, but when other children tried to take toys from her, they were rarely taken from her. However, she was not strong at all in fighting with her peers and was known as a crybaby. In contrast, a girl called TN, who had a strong fighting instinct and was respected by all children, grabbed toys less frequently from other children. We also asked Japanese and Chinese ECEC teachers to evaluate the child's fighting power and leadership, but there is no correlation between their rank within the dominance hierarchy and fighting or leadership power.

5. Adults as role models creating cultural differences

The above results may seem strange, but the answer is actually simple. They use a different approach for relationship adjustment. For example, Japanese children "first check the intent of another child and then adjust their relationship," while Chinese children "first show their intent to another child and then adjust their relationship." In either cases, if another child shows rejection, they will not seize a toy from the child. In other words, children gradually learn to respect the right of possession of others, which I named the principle of "respect for occupancy" (Yamamoto, 1991). Japanese and Chinese children understand this principle when they are three years old. There is no cultural gap but a different approach to practicing the principle and adjusting the relationship with others.

Then, why does such a difference occur? If you experience living in China and become close to Chinese people, you might understand the reason immediately. Chinese people tend to use possessions of their close friends without permission. If you ask permission each time, you may be regarded as a rather distant person.

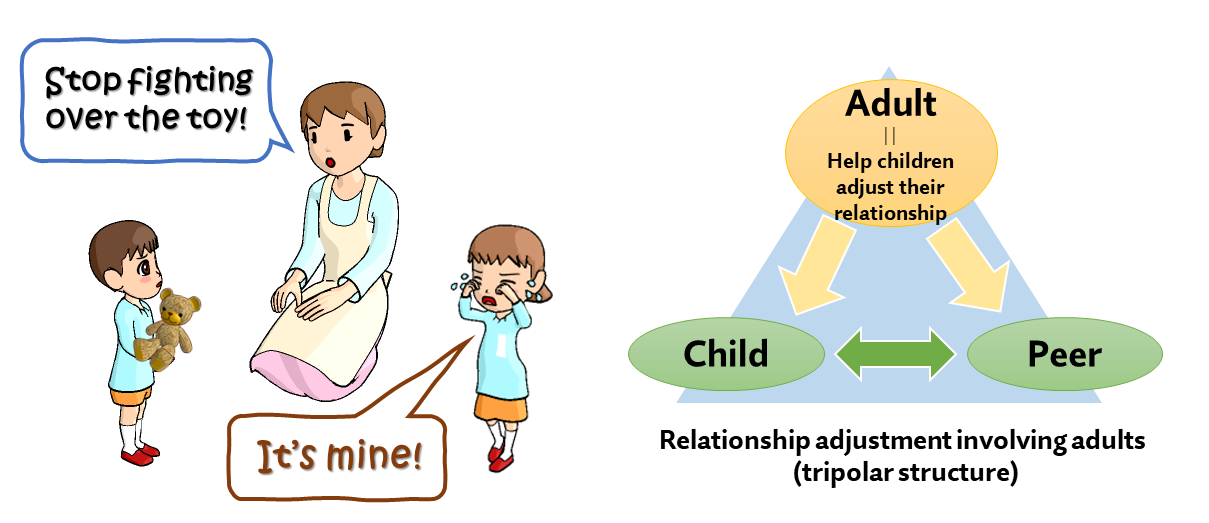

Considering the fact that such a cultural difference in adjusting a human relationship exists among adults, it should also affect children. We can instantly see it when observing one-year-old children at childcare facilities. For example, suppose children are fighting over a toy. In that case, a Japanese teacher would promptly intervene in the conflict and encourage the children to adjust their relationship, saying, "Ask him, please lend it to me," or "Take turns and share it." From the perspective of child development, when children become one and a half years old, they start observing adults who intervene in their interactions with other peers. They start learning from such interventions, and after they become two-year-old, they imitate adults' intervention approach to adjust the relationship with other peers (Yamamoto, 1997 and 2000).

In the case of the Chinese childcare centers, teachers do not ask children to "check the intent of another child first" when fighting over a toy. Of course, if their fighting becomes serious, teachers will intervene and teach them how to handle their conflict. It is generally considered appropriate to teach children the rules to address problems properly, rather than asking them to understand the intent and feelings of others.

Therefore, as you can see, the cultural differences in children's adjusting personal relationships are due to the adults' different adjusting approach. As adults act as "role models" for children when adjusting relationships with others, if this role model is culturally different, the children's behavior becomes culturally different.*1

For such cultural differences in adjusting approaches as well as in childrearing and educational perspectives, I have conducted various comparative research studies with researchers from China, South Korea, and Vietnam, including surveys on children's understanding and use of pocket money in each country (Oh, S., Pian, C., Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Sato, T., Taleo, K., Choi, S., & Kim, S. 2005; Yamamoto, T & Takahashi, N. 2007; Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Sato, T., Takeo, K., Oh, S.-A., & Pian, C. 2012; Takahashi, N. & Yamamoto, T. (ed.) 2016; Takahashi & Yamamoto 2019, etc. For the reference list, please click here). I also conducted a comparative study on different personalities in solving problems with friends in Japan and China (please see "A Comparative Study of Japanese and Chinese Junior High School Students on the Cultural Characteristics of Conflict among Friends" (PDF format) here). In addition, I have been authoring articles for CRN under the theme of "Reader Participatory Joint Research "Japan, China and Korea: What and How Do We Differ?" These studies discuss the notion that children learn and imitate adults' behavior and perceptions, and as a result, they will learn relationship-adjustment approaches that are culturally different depending on their society.*2 In this way, culture is passed down to the succeeding generations.

6. The function of role models in developing children's resilience

Considering the above discussion, a positive correlation between children's resilience and mothers' responsive parenting attitudes can be interpreted as follows:

Suppose resilience is the ability to restore the original state of oneself even in challenging situations. More specifically, resilience is a "relation-adjusting ability" that adjusts oneself to personal relationships and the surrounding environment. In that case, the next focus is how to develop children's relation-adjusting ability.

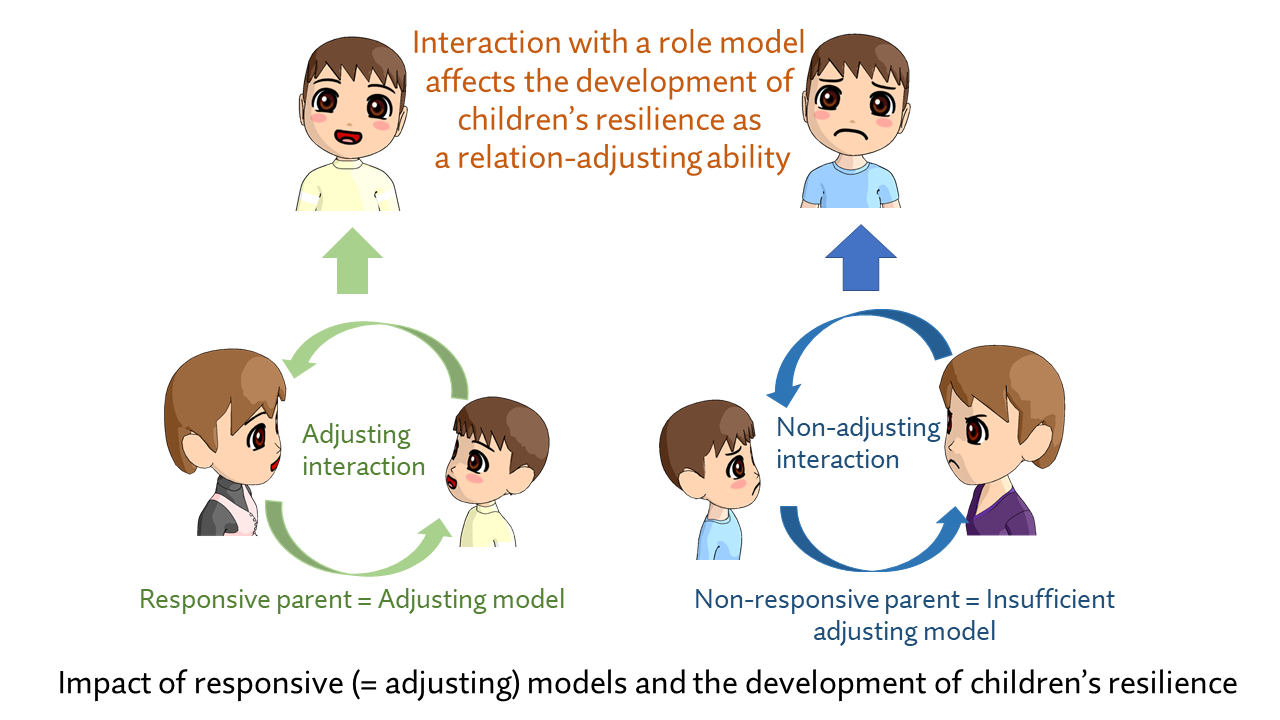

As mentioned above, children generally acquire this relation-adjusting ability by observing adults as role models. Therefore, the quality of such role models may significantly affect children's relation-adjusting ability.

In other words, if parents are not good at adjusting relationships, their child cannot have a good role model to sufficiently develop such ability. In contrast, if parents act as good role models, their child can effectively acquire the ability. Therefore, how children acquire the adjusting ability from parents depends on how parents perform as role models during interactions with their children.

The more responsive parents are, the more adjusting skills they may have when interacting with their children. Therefore, if children are raised by parents who observe and respond sufficiently, children can acquire the ability to observe and adjust to others.*3 In this way, children can nurture the ability to adjust to and overcome difficult situations, that is, resilience.

7. Significance of seven-year-old children's skills affecting their resilience

As discussed above, I suggested one interpretation regarding a positive correlation between children's resilience and mothers' responsive parenting attitudes. Next, I will explain additional interpretations regarding the factor of "emphasized aspects of childrearing" among mothers of seven-year-old children, including social and emotional skills and various other skills.

For both five- and seven-year-olds, mothers' responsive parenting is vital in adjusting relationships between parents and children. In addition, mothers of seven-year-olds emphasize additional aspects of "social and emotional skills" and "various other skills." One of the reasons I suggest is that these skills are becoming more essential techniques for children in adjusting societal relations.

In general, when children are babies, they start developing the relation-adjusting ability from emotional aspects, such as the act of crying that emotionally appeals to adults who maintain the babies' comfort state. However, as they grow, they will develop the ability more rationally by using "words" to appeal to adults. In this context, parents' "passing down skills" to seven-year-old children becomes more sophisticated than when they are five years old, which is consistent with their development status. It is also considered timely, given that those children at this age start going to school and learning new skills.

With this interpretation, it is reasonably understandable how factors closely related to children's resilience are developed.

8. Cultural diversity as a challenge toward the development of resilience

This survey contains an extensive range of aspects and requires multi-national comparison analysis. Therefore, it is possible to obtain various insights by examining the survey data from different angles.

Since I have already spent numerous pages discussing the survey results, I will only point out the possibility of cultural differences affecting children's resilience here.

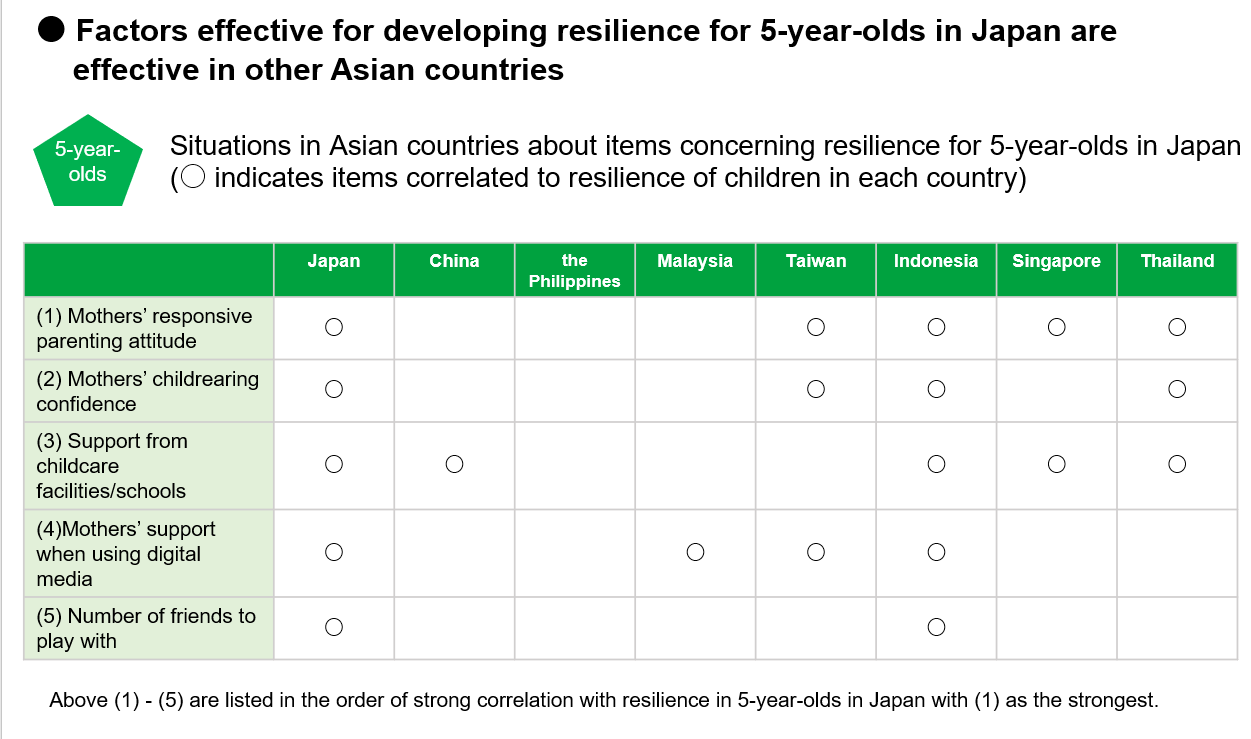

According to the section "actual conditions of resilience factors in Asian countries" in the "CRN International Collaborative Research: Survey on Children's Daily Life among 8 Asian Countries 2021 Result Report," the data of five-year-olds on factors relating to resilience are quite different depending on countries/regions. For example, only the data from Japan and Indonesia showed correlations in all five resilience factors. The Philippines data did not indicate any correlation in these resilience factors, while the data from China and Malaysia indicate only one correlation. Therefore, no factor common to all countries/regions can be confirmed as effective in nurturing children's resilience.

Why do these differences exist? What insights can we get from such results to explore the agenda of "nurturing children's resilience"?

As discussed above regarding a positive correlation between children's resilience and mothers' responsive parenting attitude, cultural differences significantly affect parents' approaches to adjusting relationships with others. Moreover, cultural differences also affect how these approaches are accepted by society as appropriate "role models" and influence their children. Therefore, we cannot say that factors strongly correlated to children's resilience in Japan have the same correlations in other countries. Rather, we should give consideration to the possibility of such differences.

Although there should be universal factors nurturing children's resilience without the impact of cultural differences, we cannot ignore the fact that there are differences in adjusting approaches that have been traditionally and culturally established in each society. Therefore, there is a limitation in determining factors nurturing children's resilience by generalizing all aspects (I further discussed this issue in *5 in Part 1). In this modern world where diversity is in the spotlight, such cultural differences are unavoidable issues that we should address when exploring ways to ensure children's well-being.

*1: In Japan, child-oriented education is historically and deeply rooted (see, for example, "Books on Child-raising" by Yamazumi & Nakae, 1978). Therefore, the concept of "adults as role models" is not emphasized on the surfece. Meanwhile, in Chinese society, where the importance of "teaching children the right things" has been highly valued for many years, the importance of "role models" is emphasized among educators. Therefore, it is common for teachers to train a particular student to be a role model for other children. This is quite the opposite of Japanese teachers who hesitate to choose a specific child as a role model. As children observe and imitate such behavior, they choose the same education style of adults as cultural role models when they grow up.

*2: The theory that children observe and imitate the behavior of adults as role models in their developmental process has been discussed over the years. One example is that the act of "imitation" is important for acquiring symbolic ability in linguistic development processes. In order to acquire the ability to share meaning with others, it is necessary to establish a triadic interactive (or joint attention) system where one pays attention to the same thing as others do (i.e., intersubjectivity skills). In addition, looking at the same thing as others is based on the system of emotional and postural resonance responses, in which the intentionality of the subject is expressed. As Dr. Noboru Kobayashi clarified, human beings are evolving to conduct organic interactions through physical synchronization, such as mothers who hear the crying voice of their baby becoming ready for breastfeeding. In this evolving process of physical synchronicity, the act of imitation emerged, and the fundamental mechanism of interactions is acquired through interactions with others. If this mechanism has cultural aspects, the passing down of culture will be achieved.

*3: This issue can be addressed from the role theory perspective (Hiromatsu, 2010). When people interact socially with others, they assume a specific role and behave according to that role. For example, a shop assistant acts according to his role of selling goods, while a customer acts according to his role of purchasing goods. In this way, social interactions (in this case, a selling and buying transaction) occur. If a person with no experience as a shop assistant needs to work at a shop as a part-timer or employee, he/she does not necessarily need to learn everything about the role of "shop assistant." The person should have observed the "shop assistant" role when visiting shops as a customer in the past, and thus, should understand how to act as a shop assistant. In other words, the role of "customer" and the role of "shop assistant" fit together like pieces of a puzzle. Each role memorizes the other's role, like each DNA composed of a double helix structure copies the helix. Therefore, if a customer becomes a shop assistant, he/she can act as a shop assistant based on such memory. This mechanism constantly emerges in the developmental process of human beings. For example, a child who keeps rebelling against his/her parents tends to take the same child-rearing method when he/she becomes a parent. Since this mechanism is universal for human beings, analyzing the survey data based on this theory may be possible.

References:

-

In English

- Child Research Net. [CRN Collaborative Research] Survey on Children's Daily Life among 8 Asian Countries 2021 Result Report.

https://www.childresearch.net/pdf/CRNA_result_report_eng.pdf - Oh, S., Pian, C., Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Sato, T., Taleo, K., Choi, S., & Kim, S. (2005)Money and the Life Worlds of children in Korea: Examining the Phenomenon of Ogori (Treating) from Cultural Psychological Perspectives. Maebashi Kyoai Gakuen College Journal Vol. 5, 73-88.

- Office of Quality of Life Measures

https://www.kindl.org/english/information/ - OH,S., Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Takeo, K., Sato, T. & Pian, C. (2009). How Does Culture Appear in Interview? ; Focus on Treating in Korea and Going Dutch in Japan. Maebashi Kyoai Gakuen College Journal, Vol 9,125-135.

- Pian, C., Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Oh, S., Takeo, K.,& Sato, T. (2006). Understanding Children's Cognition about Pocket Money from Mutual-subjectivity Perspective, Memories of Osaka Kyoiku University Ser. Ⅳ, 55 (1), 109-127.

- Pian, C. (2017) What happened in dialogical classes of intercultural understanding?: An analysis of exchanging classes between Chinese and Japanese university students, Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 51 (3), 391-402, DOI: 10.1007/s12124-017-9393-7.

- Resilience Research Centre.

https://cyrm.resilienceresearch.org/ - Sato, T., Kitano, S., Fukami, T., Hoshi, M., & Sakakihara Y. (2022). [Japan] CRNA Collaborative Research for Exploring Factors Nurturing Happy and Resilient Children among Asian Countries.

https://www.childresearch.net/projects/crn_asia/2022_08.html - Takahashi, N. & Yamamoto, T. (ed.) (2020). Children and Money: Cultural Developmental Psychology of Pocket Money. IAP

- Takahashi, N., Yamamoto, T., Takeo, K., Oh, S. A., Pian, C., & Sato, T. (2016). East Asian children and money as a cultural tool: Dialectically understanding different cultures. Japanese Psychological Research,58, 14-27.

- Yamamoto, T. (2017). Cultural Psychology of Differences and EMS; a New Theoretical Framework for Understanding and Reconstructing Culture, Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 51 (3) ,pp345-358, DOI 10.1007/s12124-017-9388-4.

- Yamamoto, T & Takahashi, N. (2007) Money as a cultural tool mediating personal relationships: Child development of exchange and possession. in Valsiner, J. & Rosa, A. (ed.)The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural Psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Yamamoto, T., Takahashi, N., Sato, T., Takeo, K., Oh, S.-A., & Pian, C. (2012). How can we study interactions mediated by money as a cultural tool: From the perspectives of 'cultural psychology of differences' as a dialogical method. In J. Valsiner (Ed.),The Oxford handbook of culture and Psychology (pp. 1056;1077). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Yamamoto, T. & Takahashi, N. (2018). Possessions and Money beyond Market Economy, in Rosa, A. & Valsiner, J. (eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural Psychology. 319-332, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Zhou, N. (2022) [Mainland China] Current situation and impact factors on children's "psychological resilience" and "subjective sense of well-being" amidst COVID-19 --Data analysis on 5-year-old children survey in mainland China.

https://www.childresearch.net/projects/crn_asia/2022_07.html - Hiromatsu, W. (2010) For Reconstruction of Role Theory. Iwanami-Shoten.

- *Oh S., Yamamoto T., Pian C., Takahashi N., Sato T., Takeo K. (2006) Multivoice Methods in Cross-Cultural Understanding (Multivoice Methods) - Focusing on how to look at the phenomenon of children treating each other. Maebashi Kyoai Gakuen College Journal, No.6,91-102.

- *Yamamoto, T. (1991). Establishment of the principle of "respect for occupancy" and its function in early children's groups - On the problems of ontogeny of possession-. The Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 39 (1991), No. 2, pp. 122-132.

- *Yamamoto T. (1997). Development of Possessive Behavior and Its Cognitive Structure in Early Childhood: a cross cultural study between Japanese and Chinese children. Doctor Thesis at Beijing Normal University.[Chinese]

- *Yamamoto T. (2000). Children beginning to form play groups: autonomous groups and tripolar structure, in Okamoto Natsuki, Asao Takeshi, (ed.) Psychology of Age, 103-142, Minerva-Shobo.

- *Yamamoto T. (2004). Children Growing Up in Culture, in Muto Takashi, Asao Takeshi (ed.) Educational Psychology, 120-128, Kitaohji Shobo.

- *Yamamoto T. (2006). Chinese Toddlers' Relationship Ruling Their Interactions over One's Possessions: Are human toddler groups organized under dominance hierarchy? Japanese Journal of Law and Psychology, Vol.5 No.1 91−98.

- *Yamamoto T. (2013). Ambiguity and Substantiality as Essential Nature of Culture: Redefinition of Culture from the Perspectives of "Cultural Psychology of Difference." Japanese Journal of Qualitative Psychology, No.12, 44-63.

- *Yamamoto T. (2015). What and Where is Culture: The Psychology of Conflict and Symbiosis, Shinyosha.

- *Yamamoto T., Watanabe T., & Ohuchi M. (2023). From Explanation-Interpretation to Reconciliation-Symbiosis: A Theoretical Examination of Phenomenology and Perspectives of the Parties on Autism for Interactive Mutual Understanding Practice. Japanese Journal of Qualitative Psychology, No.22.

- Yamazumi, M. & Nakae, K. (ed.) (1978). Books on Child-raising 1-3. The Eastern Library Series. Heibonsha Limited, Publishers.

In Japanese (* with English abstract)