* Titles and affiliations are as of the time of the conference.

Presented at Third International Conference of Child Research Network Asia (CRNA) held in Jakarta, Indonesia, September 25-27, 2019.

No Child Left Behind Stunted: Indonesia's Challenge

To reflect the Sustainable Development Goals for the Indonesian context, the title of my talk is "No child left behind stunted: Indonesia's Challenge."

Certain Post-2015 SDGs stated by the UN are relevant to our topic today.

- No hunger, year-round access to food,

- No stunted children under 2 years old,

- Food systems are sustainable for all,

- Sustainable agriculture development with100% increase in smallholder productivity and income,

- Zero loss or waste of any agricultural product.

Indonesia has two main problems now. People are still facing under-nutrition although vitamin A deficiency and iodine deficiency disorder are under control. However, stunting is affecting children's growth and development. Many children and pregnant women are underweight and anemic. On the other hand, over-nutrition is also a problem; 11% of children are already overweight. Hence, we can say Indonesia suffers a double burden. Not to mention problems faced by Indonesians due to micronutrient deficiencies, popularly known as "hidden hunger."

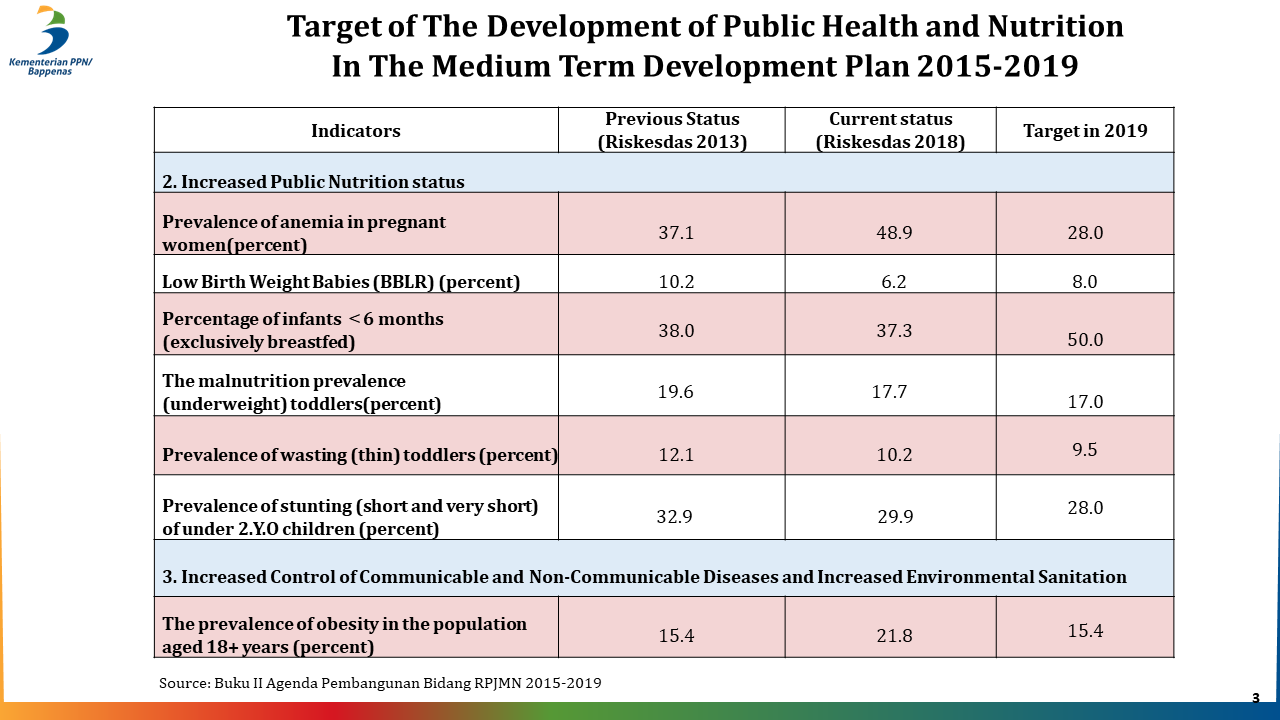

These were our best achievements in 2013 and 2018 from a national research, and in the right column, our target for the end of 2019 is shown. First, reducing anemia in pregnant women has been unsuccessful, although the target was to reduce it from 37.1% to 28%, now it's almost 50%. This is why the maternal mortality rate is still very high, 305 per 100,000 cases - the second highest in South East Asia. The second target was low birth weight babies. The figure in 2018 is below our target (8%), but 6.2% are still born underweight. Also, the percentage of breastfed infants was targeted at 50% but is still only at 37.3%. The prevalence of children under 5 with malnutrition was targeted at 17%, but is still at 17.7%. Wasting and malnutrition is still higher than the national target. Stunting is also still higher than the target. In addition, a new paradigm has emerged whereby child and youth obesity is increasing. The proportion for 18 years and older is 21.8%, higher than the 15% target. This is the landscape of our macro nutrition position.

We are at a crossroad now; one of the few countries being able to maintain economic growth at 5% for the last 15 years. Our president attends every G20 meeting on equal terms with other countries, but in terms of children's growth and development, we lag behind. If we don't improve, our future prosperity will deteriorate. It is well understood that stunting is a result of poor nutrition and health in early childhood, producing negative consequences for individuals, the communities and the national level. There is no alternative - there must not be any more child left behind stunted in Indonesia.

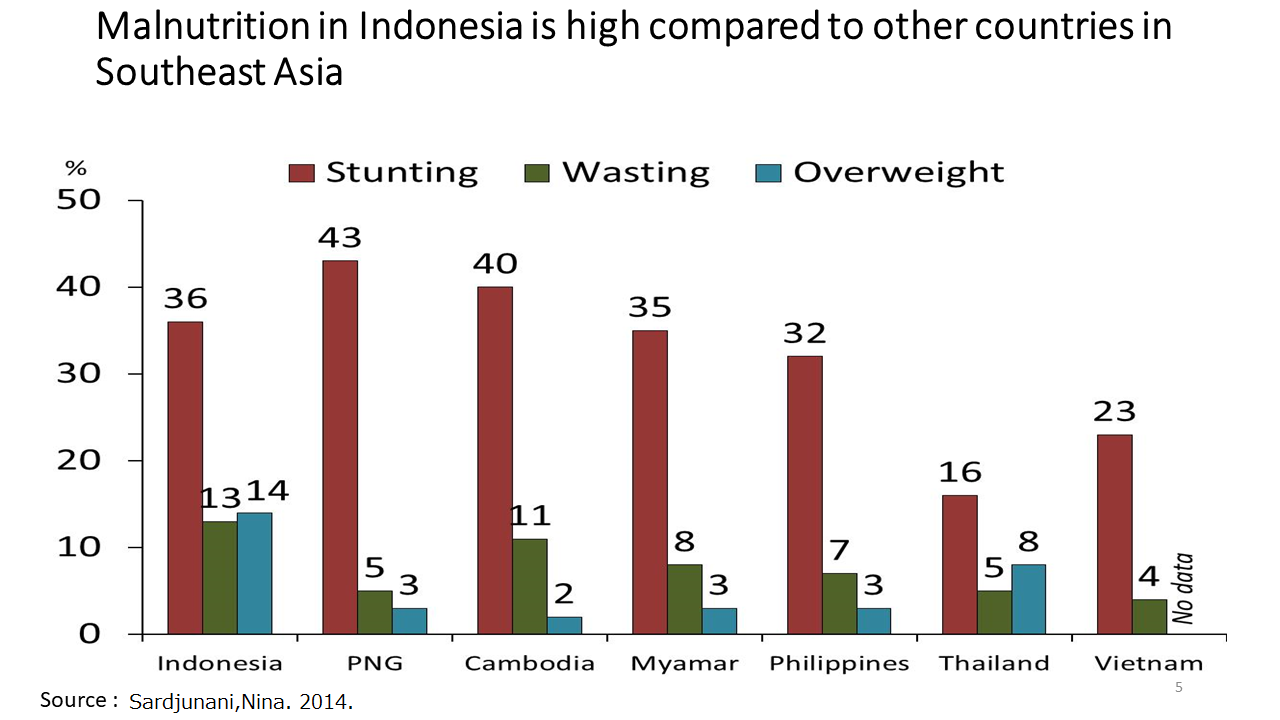

In comparison with other neighboring countries, we have lower prevalence of malnutrition than Papua New Guinea and Cambodia, but Myanmar is in a better situation, and the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam have an even lower rate. On the world map according to WHO, countries with stunting prevalence of over 30% are indicated in red, so Indonesia is colored red which shows that we are more like an African country than an Asian one.

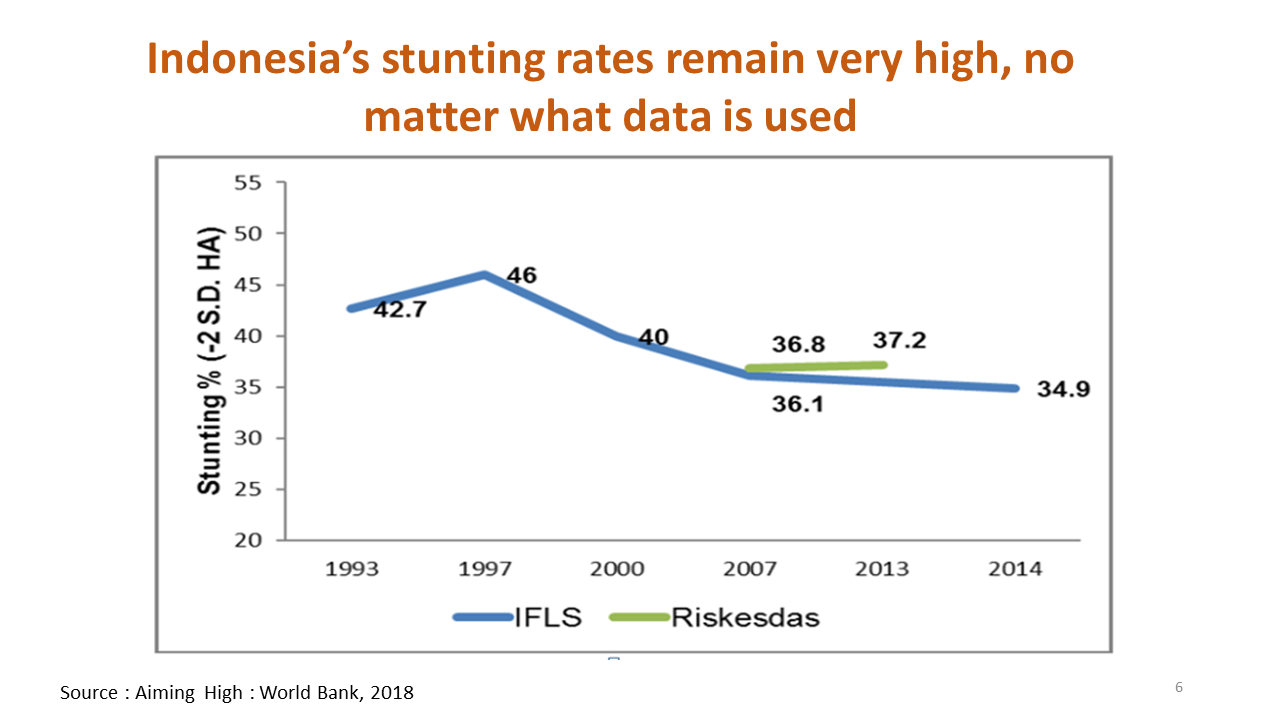

Reducing stunting has been a struggle. The Indonesian government took serious measures in 2007; for the first time, they conducted a national survey by Riskesdas (Basic Health Survey) on stunting prevalence. Unfortunately, from 2007 to 2013, the results showed it was still increasing.

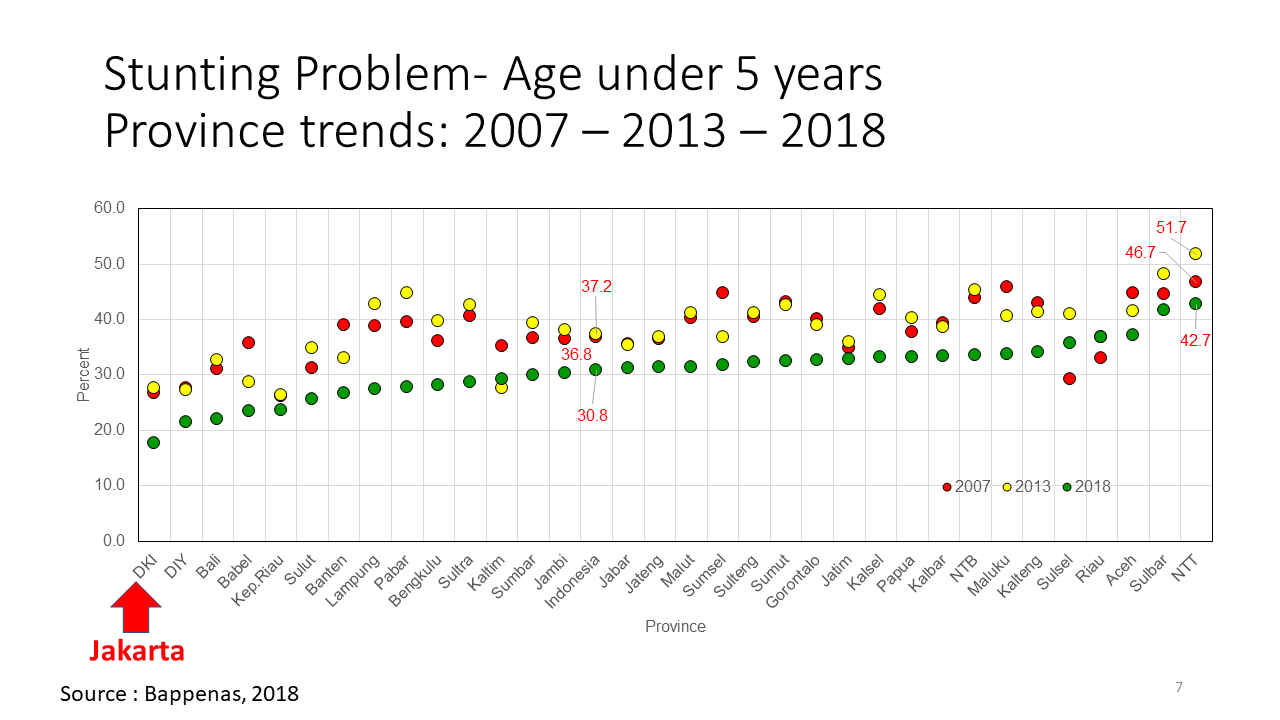

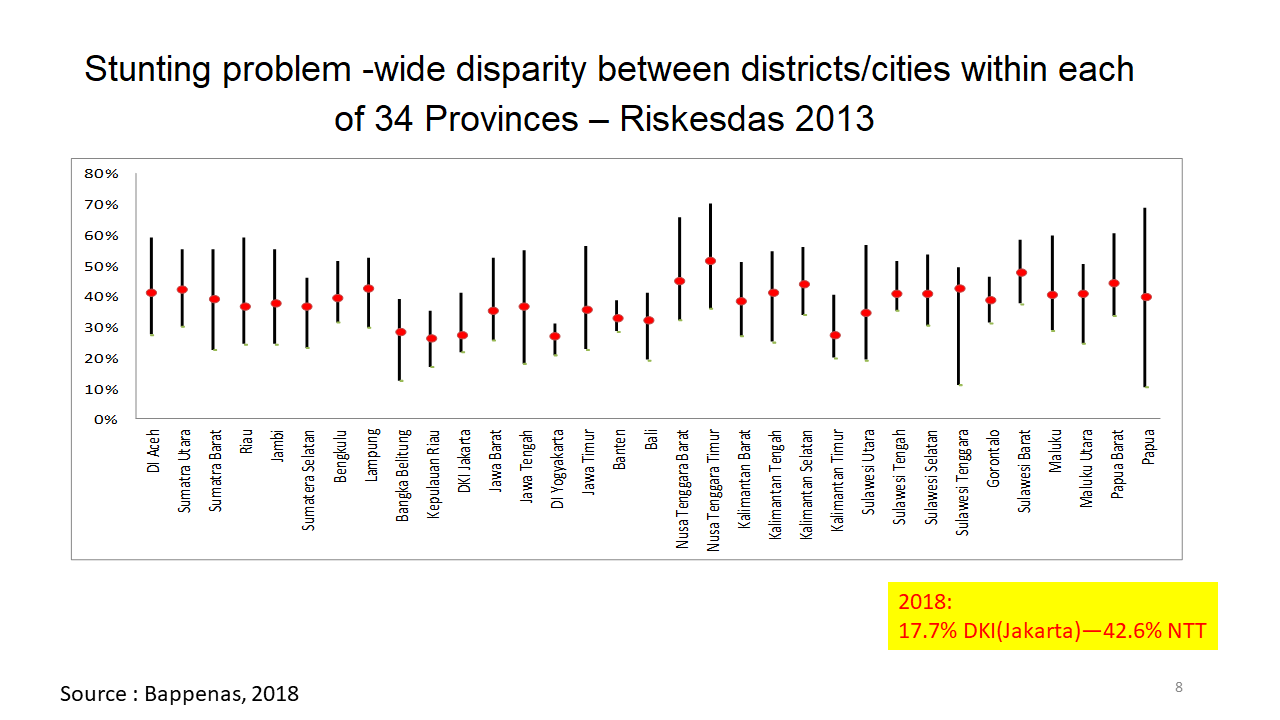

The provincial distribution also shows stunting in Jakarta is below 20%, so it is no longer a public health problem. However, there is a province where it exceeds 51%, or even some sub-districts show higher percentages, so when we talk about stunting prevalence, we cannot just talk about the national average, not even the provincial average, but about the smaller divisions than provinces.

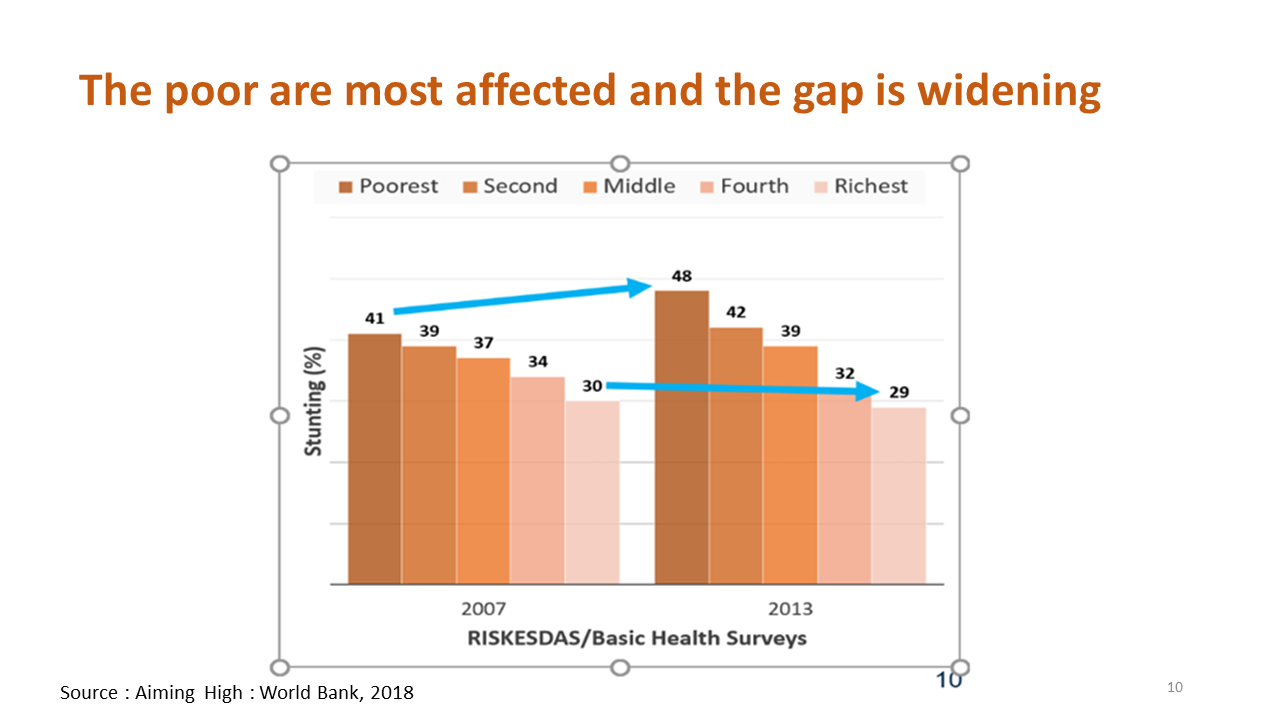

Stunting also creates inequalities. In 2007 there was 30% prevalence even in the richest households, which was reduced to 29% by 2013, but the prevalence in the poorest households increased from 41% to 48% in the national basic health survey. The poorer households are further affected while the wealthier households still have a significant number of stunting children as much as 30%. It is not just about poverty and insufficient education, but also about the quality of parenting and ecosystem of the child growth and development.

We are concerned about stunting because:

- Child and maternal mortality rates still high

- Impaired physical and cognitive development

- The decreased economic productivity, because of no.2.

- Compromised adult health and risk of intergenerational transfer of poverty or perpetuation of negative impact.

Malnutrition manifests itself as stunting, wasting (lower weight according to age), low birth weight, and micronutrient deficiencies.

Two direct causes of stunting are: Chronic inadequate dietary intake and some cases inadequate nutrition absorption due to worm infestation as well as frequent bout of infection which means the body needs more calories, coupled with loss of appetite. People are fighting two losing battles.

The followings are what we call underlying causes.

- Food insecurity

- Lack of social safety nets

- Poor dietary diversity

- Sub-optimal infant and young child feeding

- Poor parental education

- Lack of women empowerment

- Early pregnancy/Low birth spacing

- Unsanitary environments and practices

- Poor quality & demand for health services

- Poor immune system

Dealing with two problems is insufficient, we must ensure food security, domestic or imported, and providing social safety net for the needy. Poor dietary diversity means many parents and children after one year old eat unbalance dietary intake; sub-optimal infant and young child feeding refers to the complementary feeding after 6 months when mothers need to combine breast feeding with infant feeding, called MPASI in Indonesian, which is not yet successful. Poor parental education can be easily recovered in the next generation. Lack of woman empowerment means they cannot distribute resources at home according to their needs, such as food for young kids, because of poverty. Pregnant mothers and infants are left behind, so early pregnancy/ low birth spacing should be taken care of as well. The earliest marriage age for girls now has been raised to 19 with the extension of compulsory education to senior high school, so they can delay marriage and later on pregnancy.

The basic causes of all this are within the social economic, political, and environmental contexts. According to the new data from 2018 Riskesdas national research, more than 20% of the surveyed infants are below 48 cm in length at birth and nearly 7% are below 2,500 grams. These are the primary causes for stunting for this age group.

We are trying to increase the breastfeeding rate. It was successfully raised by 10% from 2007-2012 to reach 38% but has stabilized since and is not increasing.

Prevalence of complete immunization has increased, but this has no impact on the kids already affected by sickness. We still need to cover areas of low immunization such as Aceh and Papua with around 40%, although there are provinces that mark as high as 80%.

We have to start with ensuring adequate calorie consumption during pregnancy to prevent low birth weight and stunted babies. Many are still below 70% of adequacy.

The anemia rate in pregnant women was 37.1% in 2013, but has risen to 48.9% in 2018, causing a high mortality rate among pregnant women. Free iron capsules are distributed to 80% households but there is still low consumption, under 40% which is unsatisfactory.

Tobacco smoking in the households, especially among children (young smokers) is also increasing, which affects the stunting rate.

Uauy et.al indicated the consequences of stunting as follows: In the short term; impaired brain development, growth of muscle/bone, weight & height, body composition, also metabolic programming. In the long term, low cognitive capacity and education can affect community culture, immunity, locomotion, work capacity and can lead to obesity, diabetes, coronary, high blood pressure, stroke, cancer, and age-related functional loss. It is clear that stunting has a significant impact.

When coupled with infectious diseases, stunting can also increase the mortality rate in children. The probability of stunted children contracting pneumonia is 6 times higher than average. For diarrhea it is 6.3 times, 6 times for measles, and 3 times higher for other infectious diseases. Thus, in poor provinces such as Asmat or Papua, hundreds of kids die unnecessarily from combinations of malnutrition and measles and other infectious diseases.

According to Black et. al, about 3 million kids die every year because of nutrition related conditions. It also causes fetal growth restriction, stunting, underweight, wasting, zinc deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, and sub-optimum breastfeeding. Imagine how many lives could be saved with some remedial intervention.

Black et. al suggest focusing on women of reproductive age and pregnancy: provide iron tablets, calcium supplements, calories, and various supplements including vitamin A and zinc for pregnant women, neonates, infants and young children. Then follow up by concentrating on disease prevention and management including water supply, hygiene and sanitation.

If Indonesia takes up some of these interventions, we could implement 90% of what we call nutrition specific interventions, but unfortunately they only contribute 30% toward stunting prevention. Non-nutrition intervention, what we called nutrition-sensitive, like water, sanitation and hygiene(WASH), early pregnancy, and other empowerment of household makes up 70%.

If these interventions could be provided with 90% coverage and the same compliance, we could reduce the mortality rate in children younger than 5 years by 15%, 35% of diarrhea-specific mortality, 29% of pneumonia-specific mortality and 39% measles-specific mortality, 20% of stunting, and 61% in severe wasting.

However, being nutrition specific is not enough because we need to provide other nutrition sensitive interventions which is related to underlying determinants in nutrition goals and action. These are; agriculture and food security, early childhood development, women's empowerment, schooling, health and family planning services, social safety nets, maternal mental health, child protection, and water, sanitation and hygiene.

Regarding the social safety net, Indonesia provides 10 million low-income households with financial assistance, which requires a regular pregnant women and children check-up at the posyandu (integrated health post). For children of school age, if 80% presence at school is maintained, the parents are supplied with financial help toward household needs.

Not only early childhood education but also early childhood development is covered. Five pillars of the ECD policy are covered, starting with ensuring children's health; fulfilling their nutrition, psycho-social stimulation and education, parenting and protection of kids.

Women's schooling is especially important for mothers. We have an opportunity to improve children's nutrition, with appropriate targeting and using an appropriately sensitive program to support leverage of a nutrition specific agenda.

Finally, I will explain how Indonesia can overcome the stunting problem, referring to the book I've been referring to in this lecture, published by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development titled "Aiming high: Indonesia's Ambition to Reduce Stunting."

It can be done as Bangladesh, Nepal, Vietnam, Peru, Senegal, Thailand, and Brazil, managed to do it in almost a decade. We sent an official team of high level representatives to Peru and Vietnam to visit their government, districts, and villages, etc. All our Presidential candidates in the last election promised to reduce stunting.

Can they do it in one decade?

Why are our children not growing as we expected? The set-backs are:

- Impact of financial crisis of 1997/1998

- Decentralization challenge. From a highly centralized government, suddenly all responsibilities like budget, authority and power is now down to districts. They now have complete authority, and funds are channeled due to right, not responsibility.

- Weak regulations and failure to enforce them is also a major problem.

Collaboration across all sectors will be the key to success.

Our National Strategy to Accelerate Stunting Reduction

Pillar 1. National Leadership, both the President and Vice President are very committed

Pillar 2. A public awareness campaign involving numerous campaigns by the President, First Lady, government agencies, and social media endorsers.

Pillar 3. Central and regional government and community converge to prioritize nutrition intervention. All sectors are involved from central, provincial, down to the village level. The 75,000 villages across Indonesia are the first level battle. Securing nutritional food security, and providing monitoring and evaluation is also important. The Central Bureau of Statistics included stunting measurement in their annual survey which can be disaggregated down to district and municipalities (514) level. This data is freely available to see if the target is reached or not.

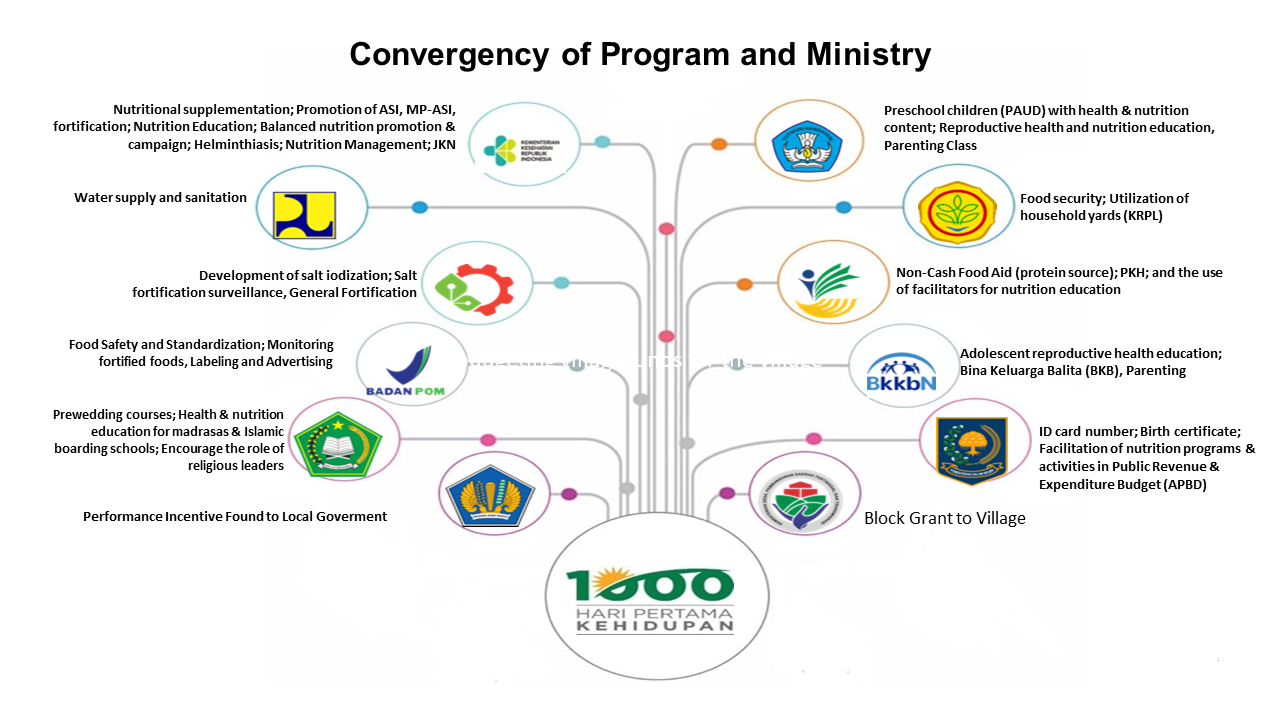

Stunting has been discussed by the President of Indonesia, involving 20 ministries in the program.

As shown in the figure, these are the departments responsible for nutrition specific and nutrition sensitive issues. Other ministries and government agencies providing enabling environment to support those ministries and agencies. Our commitment for planning and budgeting will be based on results. Annual stunting data collection will be used to give incentives or disincentives to any ministry, governor, or district.

We wish to improve the capacity of implementation at the levels of districts and villages. Human development cadres are being assigned from community organizations, women's organizations, and agriculture, working together with a coordinator, called the human development worker. The coordinator helps the people in villages to understand the significance of their data, listing stunting data by name, address and family profile, to meet the needs of all the sectors in line. At the first level funds are provided by the village, at the second level by the district, at the third level by the province, and then at the national level.

Posyandu is an integrated community health post, of which 200,000 are located throughout the country. Improvement of the staffing and operation capacity, and data usage are required. In addition, lack of competency needs to be addressed.

Children who participated in the Posyandu in the previous decade are almost 25% less likely to be stunted. So we would like to continue with this intervention.

Our challenge for district governments are planning and budgeting in which we have worked closely with community informants. Synchronizing between districts, provinces and the central district, bringing in innovation and encouraging and disseminating good practices and better evaluation and monitoring are all important in addressing this challenge.

In the nutrition acceleration program, we are trying to involve philanthropic private sectors, universities, development partners, media, government partners, and civil organizations of Indonesia. Starting from 100 districts in 2018, the intervention has spread to 160 districts in 2019, and next year we will cover 260 districts and municipalities, targeting 514 districts in 2023.

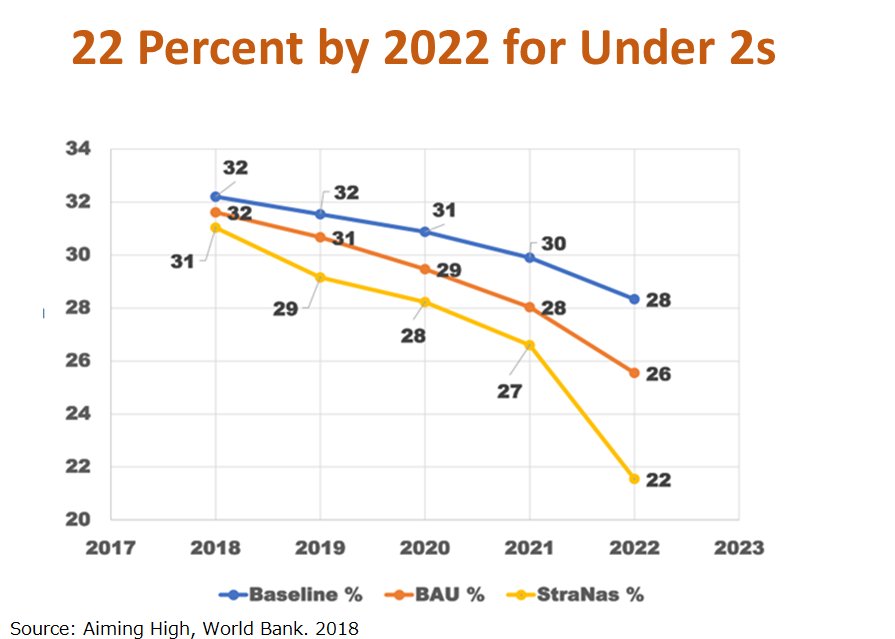

Projections of Stunting in Indonesia 2018-2022

With no action, reduction of stunting will be as shown in the blue baseline. With business as usual, it will be 26% but if action is taken it will be expected to drop to 22%. By 2030, we plan to reduce the prevalence of stunting to 19%.

Thank you for your attention.Q&A

Q1: I was very touched by your strong message.

Mothers are not taking iron, despite the provision of good campaigns since some mothers won't respond. I get the impression that a change of mindset in mothers may be needed, although the program is well-designed.

Iron deficiency anemia and malnutrition are related. Iron deficiency does not only lead to anemia, but iron is also important for the baby's brain development; babies with low iron are not doing well.

A1: Before, we used iron sulfate tablets, but since it provokes nausea and hard stool, mothers don't want to take it. They only see the emotional discomfort, and not the benefits it will bring by taking the tablet. iron sulfate also changes the color of stool.

We are now providing ferrous sulfate iron tablets. We have only been doing this campaign for a year, and is not yet a good program. The line of intervention has stopped at the posyandu level. Not enough attention being given to visits the mothers at their households.

Comment: I am a pediatrician, and I think it is hopeful that preschool teachers know which child is stunted. The average length of children at birth is 50 cm, and by 2 years old the height must be half of an adult.

What worries me a lot is the price of formula milk. In order to feed the baby, older children might get neglected. Maybe it's time we used our local resources as dietary so as not to depend on milk formula. Add oil, egg, which is the cheapest way to add nutrient.

-

References

- Badan Pengawasan Keuangan Dan Pembangunan, Buku II RPJMN 2015-2019: Agenda Pembangunan Bidang

http://www.bpkp.go.id/sesma/konten/2254/buku-i-ii-dan-iii-rpjmn-2015-2019.bpkp - Black, R. E, Victora, C G., Walker, S. P., Bhutta, Z. B., Christian, P., Mercedes de Onis, Ezzati, M., Grantham-McGregor, S., Katz, J., Martorell, R., Uauy, R., and the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. (2013). Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: Prevalences and Consequences. Presented at the The Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Nutrition Launch Symposium.

https://www.thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet//pdfs/nutrition_2.pdf - Frankenberg and Karoly,1995; Frankenberg and Thomas 2000; NIHRD 2007, 2013; Strauss et al., 2004b, 2009, 2016.

- Sardjunani,Nina. (2014). Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement In Indonesia.

https://www.slideshare.net/SUN_Movement/sun-movement-in-indonesia-brussels-nutrition-seminar - Uauy, Ricardo & Kain, Juliana & Corvalán, Camila. (2011). How can the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis contribute to improving health in developing countries?. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 94. 1759S-1764S. 10.3945/ajcn.110.000562.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. (2018). Aiming High; Indonesia's Ambition to Reduce Stunting. World Bank Publications, Washington DC.

Fasli Jalal

Fasli Jalal