MY STUDENT: I am facing a dilemma about the eleven-year-old whom I help with reading once a week. He is in the sixth grade, came to Canada from China just two years ago, has a limited vocabulary, and missed the early training to learn the English sounds of the letters of the alphabet, which he needs to decipher new words.

He arrives for our sessions, plunks himself down on the chair next to me, usually without removing his coat. I put nothing on the table we work on because he will tinker with anything to distract from our work. I ignore that and usually give him something to do with his hands, like matching rhyming words on a work sheet, arranging cut-apart sections of a sentence to form a complete sentence.

The books he picked for us to read were at his age level but he couldn't pronounce many of the words, nor did he know the meanings, so after a few weeks he refused to attempt reading, and I began to choose less challenging books. Sometimes he complied and read but often he flatly refused. I began reading to him, but stopped from time to time and asked him to pronounce a word. He'd reluctantly comply. Obviously he regarded our sessions as a battle of wits which he intended to control.

Four weeks into our sessions, I said we should have a serious talk, and I asked him how he felt about our work. He screwed up his mouth with a look of disgust, shook his head and looked down. I told him that I thought he was angry; maybe he thought the work I gave him was beneath him, too easy. He replied, "I know that stuff." I pointed out that when I asked for the facts in the story he wasn't always able to tell me, nor had he shown that he could sound out new words. "When your Canadian mates were learning the sounds of letters in kindergarten and first grade, you were learning Chinese. You know a lot about China. That tells me you are bright. You need to catch up and I am not giving up on you. I am going to stick with you until you catch up." He said I made him work too hard, that he liked to play. I agreed to play after we accomplished some work. He consented to teach me to play chess, and he grinned for the first time after he won the game.

I picked books about sharks. "No," he wanted to read about endangered species, he told me. (I gather that was one of his school projects.) "Okay. What species interests you?" He shook his head. "I'll choose one for next time and then it will be your turn," I said. We spent one hour taking turns reading about sharks, and afterwards he said that he knew "that stuff". So I asked him to write a summary. In the end we compromised and he dictated as I wrote, stopping from time to time to ask him to spell a word or give me the punctuation. Honestly, I began to enjoy our contest. He was determined to control, and I was determined to see him learn in spite of his resistance.

When I found a dead bee on the pavement, I thought I'd found a perfect snare. But, he sneered at the bee, and only complied reluctantly when I suggested that we look through the three books I'd brought, written in progressive levels of difficulty, and identify what kind of bee it was. He concluded that it was a drone. "No," he didn't want to keep the bee or take it to school and as he thumbed through pages, he claimed to know everything, so I had him tell me what each picture and page was about, and I made a written outline, which I asked him to check for spelling and punctuation errors. (Not easy to keep one step ahead of this kid.)

At the next session, spurred by a newspaper clipping about the twin baby pandas at the Toronto Zoo, he agreed to take turns reading about this endangered species. When I showed him a map of China, he began to brag about how these animals came from his country and willingly did exercises identifying like sounds in a list of words. He also wrote short, short answers to questions about pandas.

I was puzzled about what to tackle next. He was showing some improvement in being able to sound out new words, but it was still a challenge to get him to read. A new idea came to me. I wrote several paragraphs of a condensed version of an interview about Sooyong Park, a Korean photographer, who spent six months a year living in a dugout to take photos of Siberian tigers. I cut my typed page into five sections and asked him to put the story back together again. I told him that the first sentence tells what the story is about. He grinned, and began to try to match the cut marks. In minutes he thought he had succeeded, but the paragraph he'd chosen for the beginning was about Bloody Mary and her cubs coming to Park's dugout. I pointed out that the reader didn't know who Bloody Mary or Park were, so that wouldn't fit as the first sentence. Ah ha. My student found that he had to read the copy to get the paragraphs in correct order. And best of all, when our session ended, he asked to take the copy of the full interview home. At the end of our next session, I'll ask him to plan the following session and tell me what he wants to learn. I think we may both get what we want.

I remember how some friends of my son and daughter got lost when they were teenagers and dropped out of school, or got into drugs and alcohol or got pregnant. I want my young student to discover that he can catch up, and that there are interesting things to become passionate about.

CLARA HUGHES, flag bearer for the Canadian team at the Vancouver Olympics in 2010, winner of medals for cycling in summer Olympics and speed skating in winter Olympics, relates in her book Open Heart, Open Mind, experiences of growing up in a dysfunctional family. Her father was an alcoholic, but even when she watched him pass out, she didn't understand his problem. "Dad, why do you have to keep doing that? Why can't we just be together and be happy?" she thought. Her mother, a good person, the daughter of a broken family and alcoholic father, was the peacemaker but also an enabler. "When I was an adolescent, my mom had given me a book about menstruation and sex, suggesting that we look at it together. No way! Around thirteen, I started sleeping around, which was as normal for my group as drinking. I didn't know what I was doing--young drunken fumbling, random and detached from any sense of reality. The sex was never memorable, or connected with love." Clara skipped school, used drugs, alcohol and sex as an escape from her boring life. In high school she won a speed skating competition and then one day she was flipping through the channels and came upon the 1988 Olympics when Gaetan Boucher glided effortlessly across the ice to win the 1500 metres race. She thought, "I want to do that," and her life was transformed when Peter Williamson, a member of Canada's 1968 Olympic team, became her speed-skating coach. "I had goals beyond getting wasted. I was plugged into something larger than me. I was evolving as a person and learning the meaning of self-respect. Sport provided me with a value system and a moral base that I had lacked. I wanted to be good for my coach. That year I won silver at the National Championship in Calgary for the 800-meter, mass-start event. I felt pumped. My reward was earning Peter's praise and knowing I deserved it."

Mirek Mazur, a cycling coach, had watched her skate and suggested that she try out for his cycling team. "Mirek changed my life. After graduation from high school, I committed myself to the bike, and trained tirelessly. My dad encouraged me saying, 'Get out of this hellhole and don't come back.' All my coaches became father figures to me.... Winning races felt good; it filled the emptiness and loneliness, just as the drugs, and then the skating, had done." She won the bronze medal for cycling at the Atlanta Olympics in the summer of 1996.

But between bouts of success that led her to feel she could do anything, she'd developed the "what-the-hell behaviour"--staying out late partying and berating herself for loss of control and getting "fat". Her older sister, an alcoholic, haunted her. She began to realize that standing on the podium wasn't as rewarding as knowing she had done the best she could.

Clara believes that we create opportunities and either follow them or don't. An opportunity to train as a speed skater again presented itself and she went for it and became a winner.

She learned about the Right to Play, a foundation supported by Olympians who were donating their prize money to this organization that provided equipment and leadership training to countries like Uganda, Ethiopia, Ghana and Rwanda. She donated her winnings and started travelling as an ambassador for this cause. Youngsters with no shoes ran beside her as she trained. Education and the use of mosquito netting were promoted. "Even in sports you have to think how to win, so playing helps you become creative. Play is important in forming character." At speaking engagements for Bell Canada Enterprises, painful as it is, she describes her family and early destructive years, while urging young people to find something they are passionate about.

With all her Honorary Orders and prizes and Olympic medals, she came to realize that when she lost but felt good about the race, she had discovered "a metaphor for life". "Though our culture puts great emphasis on winning, the rewards aren't necessarily what we need." Guilt, needs, fears, and self-hatred from the past drag us down, she writes. Busyness keeps us from facing our demons. "Medals weren't able to fill me with self-worth." She knew she would slip back to using alcohol and excessive eating until those vulnerable issues were addressed. With psychiatric help she came to see that she could not fix what had happened, nor could she fix her father, mother or sister. Her skating teacher, Xiuli Wang, had told her that she had herself to offer to others and that was enough. She needed to accept her wounded self and to know that every issue wasn't a survival issue. (1)

JACK'S STORY - Jack (name changed) had been free of alcohol and drugs for over fifteen years and agreed to answer my questions about his addiction and recovery. He told me that he secretly began to smoke cigarettes that he got from friends when he was about six years old.

Q: How old were you when you were introduced to drugs?

J: Around 13 or 14.

Q: What was going on in your life that made you want to try drugs?

J: Curiosity really and to do something everyone said was bad just to see why everyone was saying that.

Q: Who introduced you to the first drug you used?

J: Baby-sitter's boyfriend.

Q: What drugs did you use and did you move up to stronger drugs?

J: Pot, then alcohol, LSD Mushrooms (hallucinogens) then cocaine and heroin, pretty much most street drugs.

Q. How did you feel when you used drugs in those days?

J: It was to experience something different than what I routinely felt in life, and it was interesting to learn different realities from using drugs.

Q: Did you use drugs to help you be successful in school? Make friends? In sports?

J: No, it had nothing to do with being successful. Drugs helped to accept the boring routines of adolescence.

Q: How did you get money to buy drugs and alcohol?

J: Pooled money with friends or sometimes stole from family or broke into local stores and shops to get money.

Q: What was going on in your life that made you want to quit?

J: I went through withdrawal treatments when I was young, but went back on, then decided I needed to control my life. Quitting gave me my choices back. Instead of servicing the drug addiction, I could choose to do something else more useful in my life. Even though drugs were a short fix, my choice paid off over the long term.

Q: Anything else you want to say about teenagers getting into drugs?

J: You can only get so high, then you will die. Pushing the limits has its price unexpectedly--there isn't any warning sign.

JOBIM NOVAK'S STORY - Novak told his story to Matt Galloway, host of the CBC Metro Morning radio show on Nov. 10, 2015.

When Novak was fifteen years old, he stole painkillers from his parent's medicine cabinet. He used them every day as a way to cope with his mental health issues. "You feel great--it's like being covered in warm blanket. You don't care about anything. It takes away all the mental pain."

Now at age 21 he's in recovery from his addictions and has been diagnosed with schizophrenia, for which he gets treatment. "Music helped me when I was down," he told Galloway. "I had no friends, I was addicted, music pulled me out." When he was younger he wrote poetry but while using drugs, he quit. After a time in rehab, he began to attend the Creative Writing Program run by the humanitarian agency Ve'ahavta in collaboration with the Toronto Writers Collective. Now he cultivates his talents as a poet and rapper. He believes he would be dead today if he had not had help from this agency. (2)

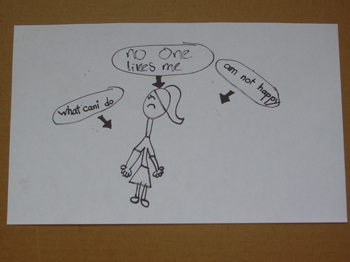

TROUBLED TEENAGERS IN THE CLASSROOM AND AT HOME - Nelsen, Lott, and Glenn write that these students often appear sad, worried, bored, tired, distrustful, angry, afraid, determined. They sit with lips clamped, and often hold their breath. They are thinking, "Am I bad? Do they like me?" Children make decisions subconsciously based on their perceptions, their private logic and life experiences. "When children feel safe--when they feel that they belong--they thrive; when children feel that they do not belong, are not significant, they adopt survival behaviour." They may rebel, seek revenge or retreat to hide their existence. Punishment for misdeeds is often ineffective. Typical punishments like having the student stay after school, phoning the parent, or writing the student's name on the blackboard, seldom works because the student thinks the punishment is stupid and they continue doing as they please, or they tell their parents that the teacher lied, or they don't care and give up. The authors write that the teacher or caregiver should give the student a way out. First, ignore the student and do something else. Second, after a cooling period, tell how you feel and what you did to contribute to the student's behaviour and that you are willing to do things differently, and ask the student to tell how they felt and what they will do in future. (3) Mia French offers other suggestions. Foster friendships by assigning the student to work one on one with other students having common interests. Boost self-image by giving them opportunities to help others, such as helping a younger child, doing a chore at home or at school. Together have the student list characteristics he would like to have in his friends and then have him evaluate how well he meets those requirements. Help him learn social skills; let him become an "expert" in a certain area; show empathy for his struggle. Show the student his progress and remind him how long it took to learn to walk and tie his shoes. (6) At times a tangible reward will pave the way for the youth to become aware of the inner rewards of doing a job well. Neighbours who get to know the parents and know teenagers by name help the child feel a part of a caring community.

THE ADOLESCENT BRAIN - Weizz & Hawley report that "...the evaluation literature for depressed youth has not been extensive and has been based largely on case studies and small samples. Studies should be specific to developmental periods.... E.g....the peak overproduction of synapses occurs [in the prefrontal cortex] at approximately one year of age, but it is not until middle to late adolescence that synapses consistent with adult numbers are obtained. Adolescents are not capable of utilizing higher-level thought processes that may govern judgment and decision making. This length of time when the individual is not a child or an adult can result in mood disruption, risky behaviours and conflicts with parents." (4) The Office of Applied Studies, 2005, reports that prior to age 10 depression is relatively rare. By late adolescence these troubled individuals present the most common public health problems, and affect 5-10% of youth. Adolescents spend more time with their peers; friendships are more intimate; the peer culture emphasizes popularity; girls increase in body fat which fractures their self-image; boys have increased muscles, their voice deepens and both sexes wrestle with their increased awareness of their sexuality. Often parents are not aware of how these changes affect their young people. (5)

CONCLUSION - In the U.S. an average of 5-10% of youth in late adolescence have public health problems related to the changes in their developing body, immature brain function and the choices they make. They sometimes function as children and sometimes as adults. We caregivers should recognize these changes and know how they affect our youth, and we should know how the youths perceive their choices and actions. There are few studies about the adolescent brain development in relationship to their behaviour changes, but good advice about caring for these troubled individuals is provided by experts who work with youth. Students and caregivers also learn from the life stories of adults who recall their adolescent years.

References:

- (1) Hughes, Clara. 2015. Open Heart, Open Mind. Simon & Schuster Canada.

- (2) "How music saved a Toronto man from drugs before he turned 21-years-old." CBC News, Posted Nov. 10, 2015 11:05 AM ET.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/programs/metromorning/how-music-saved-a toro... Retrieved Nov. 11, 2015. - (3) Nelsen, Jane, Ed.D, Lynn Lott, M.A., M.F.T., H. Stephen Glenn, PhD. 2013. Positive Discipline in the Classroom and Responsibility in Your Classroom. Three Rivers Press, an Imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, division of Random House Inc. N.Y.

- (4) Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan and Lori M. Hilt, ed. 2009. Handbook of Depression in Adolescents. Routledge, an Imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. N.Y., N.Y.

- (5) Strauman, Timothy J., Philip R. Costanzo, and Judy Garber, ed. 2011. Depression in Adolescent Girls - Science and Prevention. the Guilford Press, a division of Guilford Publications Inc. N.Y., N.Y.

- (6) French, Mia. 2004. "Put Downs & Comebacks, How to respond to a discouraged kid." Reading Rockets, WETA television station, Washington D.C. funded from the U.S. Department of Education. www.readingrockets.org.

Marlene Ritchie

Marlene Ritchie