ECCE in Indonesia: Policy and Challenges

- Part1 (This paper)

- Part2

Introduction

Since 2001, the Indonesian government has started to put extra attention to Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE). The landmark was the creation of ECCE Directorate (Direktorat Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini) in the non formal section of the Ministry of National Education (now the Ministry of Education and Culture/MoEC) (UNESCO, 2005). Since the establishment of this directorate, non-formal ECCE services are put emphasis on the government planning. As a consequence non-formal ECCE services started to flourish.

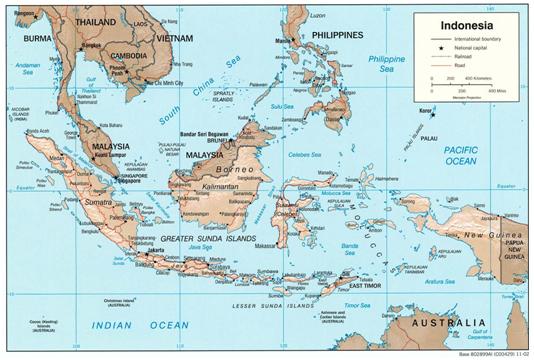

To give a little bit of context, Indonesia consists of 33 provinces with total population of 239,870,000 people according to 2010 census. Population of young children (age 0-6) in Indonesia is 31,804,759 or 13.26% of total population. There are 15,381,471 (48.36%) young children living in urban areas and 16,423,288 (51.64%) living in rural areas (BPS, 2011). Indonesia ranks as a lower-middle income country with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) USD 846,832,283,153 in 2011(World Bank, 2012a). Even though there is a slight decrease in poverty level from 13.3% in 2010 to 12.5% in 2011 (World Bank, 2012a), the poverty level is still considerably high compared to Malaysia where it is only 3.8% (World Bank, 2012b). Indonesian position of Human Development Index in education is 119 out of 187 countries. In Asia Pacific, Indonesia ranks 12 out of 24 countries (World Bank, 2012). Indonesia's national budget for education in 2012 reaches 20.2% of total development budget (Nurdiansah, 2012), but only 1.08% is allocated for ECCE (calculated from various sources: Nurdiansah, 2012 & Mulia, 2012).

FIgure 1. Map of Indonesia

Government attention to ECCE has increased the gross enrolment rate in pre-primary education from only 15% in 2000 (UNESCO, 2005) to 53.7% in 2009 (Kemendikbud, 2012). However the increase was still not good enough. Since 2010, government's attention to ECCE has become stronger. ECCE is the Indonesian government's first priority in its 2010-2014 strategic plans in education. The main focus is to increase children's access to best quality ECCE and the equal provision in all provinces, districts, and cities (Kemendiknas, 2009). There are three main targets related to it:

- to increase national ECCE's gross enrolment rate (GER) to 72.9%, at least 75% of provinces reach minimum 60%, at least 75% of cities (urban areas) have minimum 75%, and at least 75% districts (sub urban areas) achieve minimum 50%;

- at least 85% teachers in formal ECCE have a bachelor degree (4 years university degree) and at least 85% are certified, and at least 55% of non-formal ECCE teachers are trained;

- all formal ECCE implement learning program that build characters of honesty, social sensitivity, responsibility and tolerance, and most of the activities should be playful and fun for children (Kemendiknas, 2009). These three targets can be classified into two main objectives that are improving quantity and quality of ECCE.

One of important things that the government did to achieve the objectives is a reform in bureaucracy of ECCE. Before 2011, there were two different directorates within the MoEC who managed two different kind of ECCE. Formal ECCE, usually called as Taman Kanak-Kanak (TK), was managed by the directorate of TK-SD which was also responsible in managing elementary education. Non-formal ECCE was managed by the ECCE directorate. Since 2011 the government created directorate general of ECCE, Non Formal, and Informal Education called as direktorat jenderal Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini, Non Formal, Informal (PAUDNI) to manage both formal and non formal ECCE. Therefore, now both formal and non-formal ECCE are in one coordination board (Kemendiknas, 2011). According to Law of Republic Indonesia No. 20/2003 about National Education System, formal education refers to structured and tiered education. Non formal education refers to any form of structured and systematic education outside the formal system (UURI No. 20/2003).

According to the law, ECCE is excluded from formal education system. The law considers ECCE as a step to prepare children entering primary education.

However, ECCE can be organized formally, non-formally, or informally. Formal ECCE consists of two forms, Taman Kanak-Kanak (TK)/kindergarten and Raudlatul Athfal (RA)/Islamic Kindergarten. Non-formal ECCE consists of kelompok bermain (KB) /play group, Taman Penitipan Anak (TPA)/childcare center, and Satuan Paud Sejenis (SPS)/other forms of play group. Informal ECCE is any form of ECCE provided by family and/or community. Besides these three forms of ECCE services, Indonesia also have integrated service post usually called as pos pelayanan terpadu (posyandu) and young mother's program called Bina Keluarga Balita (BKB) (UNESCO, 2005). Both are services combining health services for young children and parenting education. The distinction of each form of ECCE can be seen in the following table:

| Kindergarten TK/RA | Play group KB | Childcare/ Daycare TPA |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age (year old) | 4-6 years old | 2-4 years old | 3 month old-6 years old |

| Target | Child | Child | Child |

| Focus | Pre-primary education Child development and school readiness | Child development | Care service for children of working parents; supplemented with child development |

| Opening hours | 5-6 days/week 150-180 minute/day |

Minimum 2 days/week 150-180 minute/day |

5-6 days/week 8-10 hours/day |

| Responsible government agencies | Ministry of Education and Culture - for TK Ministry of Religious Affairs - for RA |

Ministry of Education and Culture - policy and guideline development | Ministry of Social Welfare - care and social service component, supervision Ministry of Education and Culture - policy and guideline development |

| Other form of playgroup (SPS) | Integrated Service Post (Posyandu) | Program for Family with Young Children (BKB) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Age (year old) | 2-4 years old | 0-6 years old | 0-5 years old |

| Target | Child | Child and Mother | Mother |

| Focus | Child development; supplemented with additional program | Health care service combined with parenting education | Parenting education, combined with child development activities during meeting |

| Opening hours | Minimum 2 days/week | 2 days/month 2 hours/day |

2 days/month 2 hours/day |

| Responsible government agencies | Ministry of Education and Culture - Policy and guideline development | Ministry of Health - technical support, supervision Ministry of Home Affairs works together with Family Welfare and Empowerment Movement |

Ministry of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection - policy National Population and Family Planning Board (Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional/ BKKBN) |

Table 1. ECCE Services in Indonesia (from various sources: UNESCO, 2005; Ministerial Decree No. 58/2009)

SPS includes Pos PAUD, Taman Asuh Anak Muslim (TAAM), Bina Anak Muslim Berbasis Masjid (BAMBIM), PAUD Taman Pendidikan Al-Quran (TPQ), PAUD Pembinaan Anak Kristen (PAUD-PAK), and PAUD Bina Iman Anak (PAUD-BIA) (Kemendiknas, 2011). These services are provided by various ministries, agencies, and communities. The focus can be very diverse, ranging from care and health to religion and education, etc. Ministry of education and culture will commit in regulating education service in the center. For example, Pos PAUD is ECCE services provided by both posyandu and BKB. It integrates health, education, care, parenting, and child protection services. Ministries and agency involved in Pos PAUD provision are ministry of health, ministry of home affairs, ministry of women's empowerment and child protection, and ministry of education and culture, and national population and family planning board (Badan Kependudukan dan Keluarga Berencana Nasional/BKKBN).

Other form of ECCE is Holistic Integrative ECCE developed by National Development Board (Badan Pembangunan Nasional). Similar to Pos PAUD, this model integrates education, care, health, child protection, and parenting. This model, however, is still in the process of trial and development. Therefore, to this date, it has not been implemented widely. There is still an ongoing debate on the definition of "holistic integrative", whether integrated in one agency or if it refers to teachers' skills.

Quantity: Increasing ECCE's Gross Enrolment Rate

To achieve the target of ECCE's gross enrolment rate (GER), the government uses strategy of diversifying ECCE's service providers and integrated approach (UNESCO, 2005). The government has supported and mobilized non-government institutions/organizations, parents and community, private institutions, regional and local authorities to create ECCE centers. The integrated approach allows ECCE to be integrated into existing community services such as community health services (Pos Pelayanan Terpadu/Posyandu) and Program for Family with Young Children (Bina Keluarga Balita /BKB) (UNESCO, 2005). Local governments are also obliged to provide at least one ECCE in each village. These strategies are implemented since around 2002 and have been proven to increase GER quite effectively.

However, the issue of quality has been set aside. Many ECCE centers in villages do not match the minimum standard in terms of facilities and teachers' qualifications. Another issue is that there are many unregistered ECCE centers. The MoEC is now in the process of rearranging the mechanism of ECCE centers registration (Akuntono & Wedhaswary, 2011). The mechanism will be as simple as possible to motivate ECCE providers to register. This is important because only registered ECCE centers have access to government funding (Akuntono & Wedhaswary, 2011).

In Part 2 of the article, I will explain about the policy on quality improvement and challenges of ECEC in Indonesia.

References

- Akuntono, I & Wedhaswary I. D. 2011. Empat kebijakan kemdikbud soal PAUD. Kompas.com [online newspaper], December 12, 2011. Accessed May 21st, 2012

- BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik). 2011. Penduduk menurut umur tunggal, daerah perkotaan dan pedesaan, dan jenis kelamin. Accessed April 4th, 2012

- Finland National Board of Education. (2000). Core Curriculum for Pre-School Education in Finland 2000. Accessed December, 8th 2011

- Kemendikbud, Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan (Ministry of Education and Culture). 2012. Pedoman penyelenggaraan program pendidikan anak usia dini, nonformal, dan informal tahun 2012. Accessed April 4th, 2012

- Kemendikbud, Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. 2012. Peraturan menteri pendidikan dan kebudayaan Republik Indonesia nonor 5 tahun 2012 tentang sertifikasi guru dalam jabatan. Jakarta: Kemendikbud

- Kemendiknas, Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional (Ministry of National Education). 2009. Peraturan menteri pendidikan nasional Republik Indonesia nomor 58 tahun 2009 tentang Standar pendidikan anak usia dini (MoNE Ministerial Decree No. 58/2009 about Early Childhood Care and Education Standard. Jakarta: Kemendiknas

- Kemendiknas, Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional (Ministry of National Education). 2007. Peraturan menteri pendidikan nasional Republik Indonesia nomor 16 tahun 2007 tentang Standar akademik dan kompetensi guru [MoNE Ministerial Decree No. 16/2007]. Jakarta: Kemendiknas

- Kemendiknas, Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional (Ministry of National Education). 2011. Petunjuk teknis penyaluran bantuan buku dan bahan ajar pendidikan anak usia dini tahun 2011 (dana dekonsentrasi). Jakarta: Direktorat Pembinaan Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini, Kemendiknas

- Kemendiknas, Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional. 2010. Rencana Strategis Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional 2010-2014. Jakarta: Kemendiknas

- Mulia. 2012. Indonesia kekurangan 15000 PAUD. Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia, Direktorat Jenderal PAUDNI: Warta, June 12th, 2012 Accessed July 3rd, 2012

- Nurdiansah, D. 2012. Hari Pendidikan Nasional 2012. Kompasiana: opini, May 2nd, 2012. Accessed July, 3rd 2012

- Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Nomor 5 Tahun 2012 tentang Sertifikasi Guru dalam Jabatan. Accessed July 17th, 2012

- STAKES. (2003). National Curriculum Guidelines on Early Childhood Education and Care in Finland. Finlandia: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health

- The New York State Education Department. (1998). Preschool Planning Guide: Building Foundation for Development of Language and Literacy in the Early Years. New York: The University of the State of New York.

- Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia nomor 14 tahun 2005 tentang guru dan dosen [Republic of Indonesian Law No. 14/2005 about teacher and lecturer]. Accessed July, 17th 2012

- Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia nomor 20 tahun 2003 tentang sistem pendidikan nasional (sisdiknas) [Republic of Indonesia Law of National Education System No. 20/2003]

- UNESCO. 2005. Policy review report: early childhood care and education in Indonesia. Early Childhood and Family Policy Series, 10, Accessed April 4th, 2012

- Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. 2008. Appendices Analysis of Curriculum/Learning Frameworks for the Early Years (Birth to Age 8). April 2008. Melbourne: Department of Education and Ealry Childhood Development

- World Bank. 2012a. Indonesia country profile. Accessed April 4th, 2012

- World Bank. 2012b. Malaysia country profile. Accessed April 4th, 2012