Experience of Cultural Transition by Children, Parents and Teachers

From the viewpoint of children and parents, advancing from kindergarten to elementary school can be seen as a transition between two environments: from the culture of kindergarten to the new culture of school. The first half of this paper discusses the experience of kindergarten and elementary school culture in Japan based on the experience of those in transition between the two cultures of kindergarten and school, starting first with children, then proceeding to parents and teachers.

In the United Kingdom (Sharp, 2004) and Germany (Niesel, 2000), research on collaborative relations between kindergarten and elementary school has relied on interviews with a wide range of subjects, using methods such as one-to one interviews and drawings by children. The results indicate that clear differences are perceived in the transition from playing to studying and in the representation of kindergarten and school. What then is the experience of Japanese children? In previous research projects (Akita 2009, 2010), the author et al. interviewed children in three areas of Japan two months prior to entering kindergarten and two months after entering elementary school to study how they characterized their current situation and how they spoke of the difference between kindergarten and elementary school and their anxiety. This research, subsidized by a science research grant and with the collaboration of the children's parents/guardians is the second qualitative research project to be conducted on short-term cross-sectional basis. Using the same research method, a comparative study was also conducted in joint research with Professor Shing, M. L., Taipei Municipal University of Education in Taiwan where the early childhood educational system and curriculum is most similar to that of Japan.

Drawing by Children in the U.K.

"Studying A Lot is Hard"

"Different Classroom Environments"

(Sharp, 2006)

Drawing by German Children

"Homework and Rough Boy"

(Fried, 2010)

When asked about the difference between kindergarten and elementary school after entering elementary school, most children cited those features that were not parts of the physical environment of kindergarten, such as the variety of classrooms, long hallway, etc. They also mentioned having their own desk, the blackboard, and exercise equipment including unicycles, and things they found in the science room, etc. On the topic of studying, their responses were general and vague, such as "We study every day." As for patterns of activity, they cited gathering at the sound of the chime in elementary school whereas the teacher had called them together in kindergarten. A low percentage of responses cited the procedure for activities, such as kindergarteners starting the day by putting their bags on the desk and singing while in children in elementary school all rise at attention at the beginning of the day before studying, and playtime only consisting of the main recess and lunchtime. It appears that two months after starting elementary school, they are at a stage where they perceive physical differences with their bodies and they are not yet able to express and verbalize behavior and communication within themselves in a specific manner.

Drawings by Japanese children (Akita et al., 2009)

"Playing with Friends"

Drawings by Japanese children (Akita et al., 2009)

"Staying Inside because of Hay Fever"

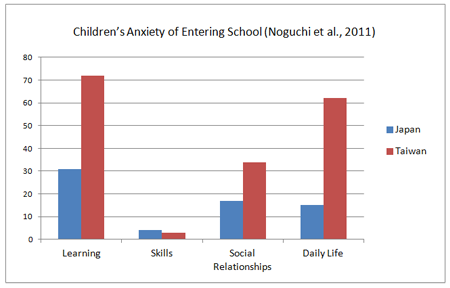

Moreover, when responses of children in Japan and Taiwan regarding anxieties related to entering school are compared (chart1, 2), children in Taiwan express a variety of concerns overall. This appears to depend to a great extent on differences in how they speak about school and their activities soon after entering school. In all countries, students' concerns focused on homework and language skills related to reading and writing. Internal differences were seen among the countries, in particular, regarding social relationships. Children in Taiwan expressed concern about their relationship with the teacher and children in Japan worried about peer relationships, such as possible bullying by classmates. As for everyday life-related concerns, children in Taiwan cited fear of being scolded by the teacher for tardiness and other reasons. In Japan, children cited matters pertaining to everyday life, such as school lunch and going to and from school, for example. This seems to point to cultural differences in the teacher-student relationship.

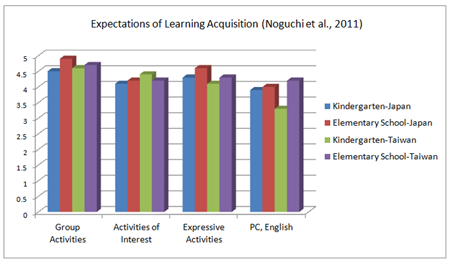

Cultural differences were also seen in surveys with parents that asked about how they prepared children for school. In contrast to respondents in Japan who spoke about preparing a study environment complete with supplies and other equipment and establishing daily life rhythms and habits, etc., respondents in Taiwan overwhelmingly talked about preparation for adapt to school learning. This suggests that during the transition period, the concerns of parents in Taiwan, where children study the phonetic symbols immediately after entering school, become increasingly more specific than those of parents in Japan. These parental expectations also reflect the different writing systems in the two countries. The Japanese syllabary consists one symbol per syllable, which is relatively easy for children to learn, whereas in Taiwan children must learn Chinese characters. As for changes in parental expectations before and after starting school, parents in Japan showed the greatest change in their expectations for social relationships, including everyday life habits and group conduct, and growing interest in art, music and physical education as expressive activities. In Taiwan, however, whereas parents indicated low interest in personal computers and other new technology and foreign language learning, interest in these subjects grew after children started school. The study showed that culture also accounted for differences in parental expectations and the image of elementary school. This consequently indicates that it is important to consider what kind of expectations and image of school should be fostered in parents.

chart 1

chart 2

Besides children and parents, an increasing number of teachers are experiencing both cultures though the teacher exchanges between kindergarten and elementary school. This study also collected and analyzed survey responses of teachers involved in these exchanges and their statements of the experience. These were then categorized into "Experience of Time and Outlook," "Instruction Plan and Preparation, " Educational Materials and Tools," "Instructional Methods," "Communicating with Children," "Understanding Children," "Playing and Studying Awareness," "School Organization (Colleagues)," "Recordkeeping Methods," "Terminology," "Relationship with Parents/Guardians," "Awareness of the Partner Schools," and "Myself and my Emotions as a Teacher." Teachers who moved between elementary school to kindergarten and vice versa first pointed out the different experience of time, an indication of the large effect of time on adaptation. These teachers returned to their schools after one or two years, where they applied this experience creatively in instructional plans and curricula as well as in the learning environment and activities. This indicates that a successful transition and connection requires not just organizational collaboration, but also people with experience in both cultures.

Educational Policies and Practices for Kindergarten-Elementary School Collaboration in Japan

In the first section of this paper, I addressed this issue from an individual, microcosmic perspective. In the second half, it is viewed from a macrocosmic perspective that considers the policies and practices of the nation and government organizations. In Japan, collaboration between kindergarten and elementary school is both a new and old topic. Since the 1920s, it has undergone several changes and has now become a hot topic. What is considered necessary to the particular form of collaboration and transition depends on the age. Today, one fundamental requirement is effective education through consistent curricula from kindergarten to high school. Another is the "first graders' problem" i which needs to be dealt with urgently.

Policies at the national level include promoting collaboration and exchange between kindergartens and schools along with revising guidelines for kindergarten education, day care facilities, and elementary school educational instruction as well as drawing up the starting curriculum at elementary schools and requiring the creating and sending of day-care guidance records.

According to a government survey, collaboration between elementary schools and kindergartens was only 23% at the prefectural level and in urban areas and only 20% in municipalities. This resulted in the "Report on Promoting Collaboration between Early Childhood Education and Elementary School Education" in November 2010. This report emphasized establishing a transitional period and the role of the board of education. The report understands the development of learning from early childhood and childhood as one that starts with an awakening to learning to lead to self-aware learning. As such, it specifies required educational content and sets forth clear educational goals, educational curriculum, and the relation between educational activities to promote understanding of those involved in both kindergarten and elementary school education.

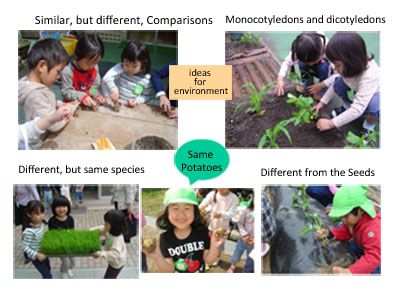

Efforts at the local government level can be largely classified into four types: first, organizations to facilitate collaboration by school district, including councils for communication between day-care centers, kindergartens, and elementary schools; second, creation of original local curricula that emphasize continuity in day-care and education programs from 0-8 years of age; third, promoting deeper mutual understanding among specialists in early childhood and elementary school education and concrete measures through mutual visits by day-care, kindergarten, and elementary school teachers to day-care facilities and classes; and fourth, social communication between pre-school and school-age children. A program in Tokushima prefecture seeks to promote a process of learning that will span pre-school and elementary school; it aims to stimulate the ability to think by focusing on "comparative thinking, relational thinking, and analytical thinking" and activities of "awareness, feeling, thinking, engagement, and acting." For example, in one kindergarten, monocotyledons and dicotyledons were planted next to each other to allow children to discover for themselves that even among potatoes, there are the different kinds. As a part of a year-long program, it is designed to foster the ability to think through repeated inference from experience.

In Chuo Ward, Tokyo, collaboration among day-care, kindergartens and schools focuses on particular content and goals in fostering, for example, "awareness of numbers, quantities, and shapes" in order to encourage reflection on the organization of the environment around them and how activities are carried out. With particular emphasis on continuity from age three to the lower grades of elementary school, this program compiles instructional materials based on children's experience of numbers, quantity and shape to visualize the meaning of their experience, promotes teacher awareness, an environment that lends itself to classification, and draws up proposals on day care based on the views of both teachers at preschool and school. The process of discussion is important for both specialists to reach a deeper level of knowledge.

Tokushima Prefecture Program (Sasaki, 2010)

Tokushima Prefecture Program (Sasaki, 2010)

Based on the above, first, as a way of ensuring continuity in experience and learning, it is important to provide occasions that will help children and their parents/guardians to understand the aim. Clearly explaining to parents the differences between elementary school education when they were children and now and how they should prepare will minimize their anxieties and prevent expectations that are too high. Second, collaboration and exchange between teachers is an effective way to promote specialized knowledge of children, their views and understanding. This does not mean that day-care centers and kindergartens will become similar to elementary schools; rather, providing experiences appropriate to the level of development will raise the level of education and is crucial to ensuring equal opportunity in education. Third, adopting the viewpoint of continuity and collaboration will clarify the significance of the daycare environment and its activities and thus contribute to making them more effective. This can be seen not as a top-down effort from the national government, but one that takes root regionally to develop local knowledge in the practice of diversity.

While the work of one,

We do not work alone

Now the past blossoms,

The buds of the future are full now.

These are the words of the Japanese potter, Kawai Kanjiro. I would to ensure that all children receive quality day care and education through collaboration and continuity from preschool to elementary school and together make the future bloom.

i The "first-graders' problem" refers to behavior that lasts for several months upon entering the first grade in which a child is unable to participate in activities as a member of a group, sit still during class, or listen to the teacher, etc. Although in the past, this behavior was seen to subside after about one month, it now continues for a longer period of time, which has focused attention on the relation to early childhood education and parental attitudes before entering school.