Malaysian Children and Disability

In Malaysia, a disability is a multilayered and complex phenomenon. It not only entails examining the medical facets but it also explores the historical and sociocultural roots of what makes Malaysian parents' perspectives on disability differ from others. The understanding of disability depends on the category. For example, a "social" disability would not warrant the same types of assistance as a "medical" disability defined by the World Health Organization. A social disability refers to the social conditions that impact the mental health of an individual (UNICEF, 2014). Furthermore, according to Malaysian tradition, mental illness would not qualify as a disability, as this is thought to be a social condition and not a medical condition (Abdullah, et al., 2017). In other words, it is seldom thought that one is impaired if afflicted by a mental illness. This type of tradition has implications for how disability is defined, and accommodations are made, perceived and viewed which ultimately affect success among other aspects. Unless the child's disability or conditions are physically noticeable, their learning difficulties may not be recognized in the ways that school professionals consider as a disability.

The World Health Organization defines a disability as one that impacts children's mobility, verbal ability, vision, comprehension, functional capacity, and behavioral problems (2007). Others, such as the Disability Act defined a disabled person as one who has a long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment which in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society (2008).

Malaysia is located in Southeast Asia with a multiethnic society, and a mixed population of Malay, Chinese, and Indian. The cultural and traditional values, including religion, play an important role in parental perceptions regarding their children's development. Approximately 5.1 % of children aged 0-14 in Malaysia have some kind of disability (World Report on Disability, 2011). One in two children registered as disabled in East Malaysia are out of school (UNICEF, 2019). The government of Malaysia formally adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2010 to promote their inclusion.

Studies show that some Malaysians do not understand the concept of disability (UNICEF Malaysia, 2016) although 77% of the people recognized that disabilities can have congenital and genetic causes or result from accidents or diseases. A significant number of parents believe that a disability is caused by the 'will of God' (10%), the fault of parents (4%), or fate/Karma(2%) [UNICEF Malaysia, 2016].*1 At the community level, a disability is still subject to deep-rooted taboos. Strong religious and cultural beliefs around disability being linked to past misdemeanors can hamper people's understanding of what causes impairments. Therefore, there is still a strong assumption that having a disability implies a state of abnormality, dependency and a need for specialist provisioning. This essay discusses the Malaysian's parental perceptions about children's disability, related to the cultural values, beliefs, and traditions. Parental perceptions are defined as beliefs about disability, cultural and educational backgrounds (Islam, 2015).

Malaysian Parents Perceptions about Children with a Disability

Malaysian parents have mixed perceptions of children with disabilities. Some accept the disability as God's will, while others have negative and pessimistic feelings, embarrassment, feeling withdrawn or even rejection of the existence of children with disabilities. Many have stigma that affects their health as well, such as restless sleep and depressive symptoms. This may happen, especially when the efforts that are made seem to be fruitless, and feel unable to educate or care for their disabled children. However, these perceptions depend on parents' age, gender, faith, education, and employment status (UNICEF, 2016). In addition, the child's type of disability and age are also taken into consideration.

In Malaysia, influences of stigma, shame, and rejection associated with disabilities are more prevalent than in other developing countries. In fact, 56 % parents agree that a disability may reflect poor parenting (Shukeri & Othman, 2017). Some parents have stigma about having a child with a disability and experienced a negative feeling (Feng, 2019). Stigma can often be associated with rejection, devaluation, that involves confinement to a specific set of standards, values, and stereotypical perspectives about someone's abilities.

Malaysian parents tend to be protective and actively involved with the lives of the children due to the culture of collectivism. Chinese parents are strongly influenced by Confucian philosophy, whereas Malay parents believe in Islamic teaching, and Indian parents follow Hinduism (Author, 2005). Their belief that parents are responsible for training their children's behavior patterns, such as being obedient, never questioning parents and following their orders, and exercising self-control. These strict, overprotective, and authoritarian parenting styles, in general were normal practices among older generations (Author, 2005). They also tend to be actively involved in their children's development particularly in education.

Parents beliefs place a high value on academic achievement as one of the keys to be successful in life. They expect their children to succeed in education, however, they believe that having a disability will constitute a great obstacle to the fulfillment of family expectations. Parents feel very stressed, ashamed, and find it difficult to accept that their child performs poorly in school due to a learning disability. Influenced by the myth of being a model minority (Hu, 2022), parents see disability as indicating their failure as a parent. In Asian culture emphasis is placed on success in education, and respect for elders, obedience, and hard work are required to achieve upward mobility (Author, 2005; Kim et al., 2021).

Families described disability as a form of karma or a curse for previous wrongdoing, beliefs that are rooted in the moral model of disability (Gowramma et, al, 2021). It is believed that a disability is the result of karma or is a sign of the person's or their family's moral weakness. Parents and families of children with disabilities are thought to be morally responsible. Being feared of "losing face," parents may opt to remain quiet about their child's disability, refrain from seeking a diagnosis, hide the child away from the public and these actions further perpetuate the stigma (Wu, 2002).

Hu's study found Chinese fathers believed that diet and genetic factors are the contributing factors to children suffering from autism, whereas mothers reported they violated the pregnancy taboo and noticed that her child was delayed in language development (2022). Both parents reported similar feelings of shock and unacceptability when informed that their child has autism. The father went into denial and became angry when he became aware that his child had autism. Disbelief, resistance, and keeping the information secret tends to save face as they feel embarrassed at not being perfect (Hu, 2022).

All of these factors, which contribute to the parents' stress level, were related to the children's characteristics and behaviors of disability, not the children's age (Abdullah et al., 2017). The stress level of parents does not diminish as their children with a disability become older. Parents whose children have been diagnosed with autism experienced higher stress compared with parents of typically developing children (Shukri et al., 2017). This is because of their children's inability to adjust to environmental changes and because of this many parents have difficulties in developing a firm parenting style and become very protective of their children with a disability.

In terms of coping strategies, the father used rationally focused strategies such as trying to understand the disability by obtaining more information from books and networking with other parents that have the same issues. Mothers shared their sad experience with others and sought information through religious and spiritual teaching (Sukeri, et al., 2017). However, fathers and mothers shared similar expectations regarding their child's future. They were hopeful that their children could be independent and have a bright future in their life.

The Study

This case study interviewed four parents from Malaysia with different ethnic backgrounds about their perceptions on children with disabilities and their experiences with support from families and community. The ethnicity of the parents were Malay, Chinese, and Indian.

Malays make up the largest proportion with 69.7 %, followed by Chinese at 22.8%, and Indians at 8.6% (Bee & Ahmad, 2024). Malays, Chinese, and Indians maintain harmonious relations, emphasis on family and self-respect and promote collaboration among all ethnicities. Cooperation and loyalty are valued in Malaysian families through the practice of filial piety among family and kindship.

Most Malays are Muslim, practice Islamic culture and traditions which influence their belief in God to determine the faith of their life and future. Their politeness, respect, courtesy as moral values, and family-orientated are based on Islamic teaching. However, they are less focused on economic matters, and devoted Muslims prioritize looks and social status. In addition, they avoid criticizing, insulting, causing embarrassment or shame to others. Furthermore, they make use of non-verbal communication and tend to be subtle and indirect, re-phrasing questions, avoiding things that offensive (Shukeri & Othman, 2017).

Most Chinese are Buddhist and some follow Confucius teaching as a way of life. This ethnic group is business-savvy and has the highest income and dominates roughly 70% of the Malaysian economy (Aminudidn, 2020). They are known for hard work, are highly focused, exhibit great diligence, and resilience for being aggressive to purse the goals in their lives (Aminudidn, 2020). One of their family traditions is the emphasis on education of their children and parents sacrifice their wealth to materially support their children's success in education. On the other hand, the Indian population has class stratification between elites and low income people. The majority of them follow Hinduism as their main faith that influences their traditional beliefs. One of the central beliefs in Indian culture is Karma. Karma is "the influence of one's actions on one's present and future lives" (Doniger & Gold, 2024, p.1) and the individual's deep bonds to family, society, and the divinities associated with these concepts. Indians believe that Karma often helps people cope with these situations. They are actually responding to the generosity that bore them into a world suffused with life and possibilities (Doniger & Gold, 2024).

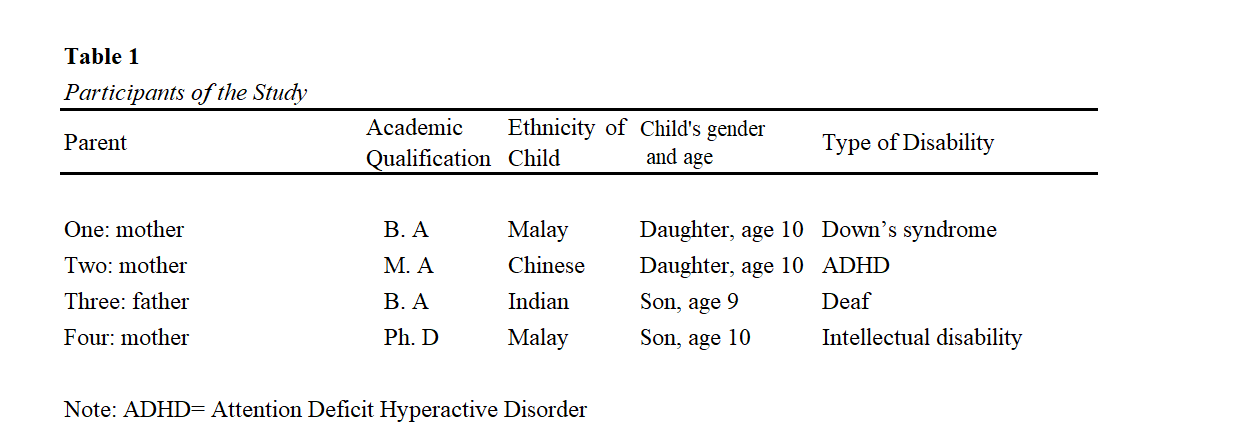

Parents from middle class families, aged between 34-40 years old participated in the study. One parent was a father and three were mothers. Two parents have baccalaureate degrees, one has a Master's Degree and one has a doctoral degree. They reside in a multiethnic metropolitan city. See Table 1 below.

The parents were interviewed using four open-ended questions for approximately 120-150 minutes for each parent. The questions were as follows:

- Tell me how you feel about your child having a disability

- How do you feel about your child's future?

- What is your experience with your child with a disability in the family and at school

- What is your experience of educational support you received in the community?

Data was transcribed and coded (Saldana, 2021) into four themes: God destiny, parents' perception, parents' feeling, family, school and community support.

Results

God's DestinyTwo parents (Parents One and Three) accepted the diagnosis of their children with disabilities and considered that having a disability was God's will. They felt that they understood that their children had special needs.

Parents Two and Four felt God was unfair because he had given them children with special needs. Parent Four and her husband have the highest degree in education and can find no reasons why her son has an intellectual disability. They perceived disabilities as an issue deeply rooted to taboos. Parents One and Three further believed that disability is caused by the "will of God," is the fault of parents, or is because of karma. Strong religious and cultural beliefs around a disability being linked to past misdemeanors can hamper people's understanding of what causes impairments. They assumed disability implies a state of abnormality and dependency and so services to children with a disability was considered as an act of charity instead of a right of entitlement. Parent One mentioned "that the perceptions these people held about disabilities came from superstitions in Asian culture that bad things could only happen to people who have done wrong; seen as bad karma inflicted on the family for past moral wrongdoings and disability seen as "punishment."

Parental PerceptionsParents did not perceive their children with disabilities based on differences in age at the time of diagnosis but based on parents' ages and educational backgrounds. Younger parents; Parent One and Parent Three, were more accepting of their children's disabilities compared to Parent Two and Parent Four. Parent Two and Parent Four have advanced educational degrees compare to Parent One and Parent Three. Parent Four stated, "I don't understand why my son was diagnosed with having an intellectual disability, he is doing well in school."

A study of factors associated with depressive symptoms in Asian men, found that adherence to masculine norms such as competition, dominance, and avoidance coping strategies were associated with depressive symptoms, while the endorsement of Asian cultural values, self-reliance, and emotional control were not associated with depressive symptoms (Hasnain et al., 2008). These results, combined with the results of the current study, suggested the merits of a thorough investigation of the effects of Asian cultural values and masculine norms on the physical health and depressive symptoms of father (Parent Three) of a child with a disability. Perhaps such masculine norms or other aspects of Asian cultural values, such as focusing on group harmony and "saving face," discouraged fathers of children with a disability from engaging with sources of support from informal and formal social networks. This can be attributed to the concept of saving face. In Asian culture, face is defined as one's respectability, prestige, and positive social value, as ascribed by others (Wu, 2002).

Most families in the current study perceived that their children can be successful in academic performances despite of challenges they faced in having disabilities. They put constant pressure on their children to be more successful academically. Most parents felt that they were failures as parents, and chose to place their children in special education such as in private boarding schools to receive a good quality special needs education and services. All the parents agreed that "Being the second best was not enough. I expected my child would attend college and receive a degree and will have a good job and better future."

Parents were worried that discrimination, alienation, and prejudice in schools and in public space would have a detrimental effect on their children's development. Parent One said, "People gave me a strange look when they saw my daughter (with Down's syndrome)."

Parents' FeelingsParent One and Parent Three stated that they could not understand and recognize the potential of children with disabilities. Parent One felt that her life was in a crisis. She was shocked, confused, and felt sad. "The sadness of having a child with a disability is heavier than the sadness of death," she said. Parent Three struggled to navigate through various resources to help his son. These are common reactions that parents experienced. Parent Four said, "Having a child with a disability, the sadness lasts a long time, throughout life." The more severe the level of disability a child has, the more it makes parents feel confused and sad.

Among the three mothers in this study, Parent One had seriously experienced fear of stigmatization due to having a child with Down's syndrome. She has high levels of depressive symptoms. The mothers' depression, caused by fear of stigma, is correlated with variables from social support (support from family members, friends/coworkers, and community). Her family members distanced her from family events such as birthdays and other cultural holiday events.

Furthermore, the cause of stress and depression due to having a child with a disability is the need for medical care, particularly if a child with a disability also has a physical condition that requires intensive care. Parent Three had to go to a special class to learn sign language to help his son with school work. Feeling stress and ability to find the right solution and using the right coping mechanism are extremely challenging for the parents and family. Furthermore, feelings of isolation, financial inadequacy, pressure in the household, community acceptance, and hopes about the future of children with disabilities worried the parents.

The perception of parents about the feeling of failing to be good parents and overwhelmed by caring for children with disabilities was agreed by two parents (Parents One and Two). Parents One and Three felt pessimistic about the future of their children with disabilities.

However, Parent Four did not feel that she had failed as a parent even though she was overwhelmed by caring for her child with disabilities.

All parents felt that they were concerned about their children's education and future employment. Parents feel burdened by having children with disabilities, such as a lack of quality time with other family members, financial difficulties in accessing quality services for their child. These stresses directly undermine caregivers' psychological well-being and quality of life.

Parents who experience depressive symptoms reported that they have a lower level of physical health as well. Mothers reported significantly poorer physical health than did fathers. Mothers (Parents One, Two, and Four) also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to the father (Parent Three).

Parent Three self-reported his physical health was higher among fathers with higher levels of educational attainment, while fathers' work outside the home played a detrimental role in their self-reported physical health. Similar results were reported regarding the impact of education and employment status on fathers' depressive symptoms that confirmed a significant and negative relationship between parental age (not the age of the child with a disability) and stress. Parents of children with a disability did not exhibit the same pathways to better physical health and depressive symptom outcomes. However, this factor depended on the parenting style. For example, Parent Four used an authoritative parenting style to a lesser extent than the other three parents who were younger than her. Authoritarian parenting contributed to higher levels of parental distress (Author, 2005).

The child's age was found to be negatively related to fathers' depressive symptoms. Fathers with a younger child with a disability were reported to have greater depressive symptoms due to the fear of stigmatization (Hu, 2022). For fathers, only individual characteristics (such as parents' age, educational attainment, and employment status were found to be significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (UNICEF, 2016).

Family and Community RelationshipMost parents felt that their extended family and society were reluctant to accept the existence of children with disabilities. They were concerned about the children and were pessimistic about their future. Mothers reported significantly higher levels of perceived overall social support than fathers did. However, mothers who received social support from other family members and friends/co-workers and were involved in the community reported having lower levels of depressive symptoms. Parent Three who was physically healthier and willingly accepted his child's learning disability, received support from family members and friends/coworkers.

Parents often find themselves quite isolated as they struggle to find appropriate information, financial, and social protection (Sukeri et al., 2017). The mothers often take the responsibility of raising a child with a disability, take her/him to the hospital and accompany them to school and rehabilitation centers. Sometimes mothers feel unsupported by the family's members, communities and service providers, "partly because of the negative attitudes prevalent toward disabilities which they have experienced as feelings of shame" (Sukeri et al., 2017, p. 428). Parent Two said, my mother always warned me to keep an eye on my daughter's behavior when she was shopping, "Don't let her pick things up that we are not going to buy."

Community support and government benefits were not significantly correlated, only annual household income correlated positively and significantly with mothers' self-reported physical health. Mothers with a higher annual household income reported better physical health (Sukeri et al., 2017). According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (2024), individual with BA degree earned below RM 4,360 (USD 1,008), MA degree earned RM 4,361-9619 (USD 1,009- 2,224), and for PhD. holders earned RM 9,620 (USD 2,225) and above.

For fathers, education and employment status were correlated with physical health; fathers with higher educational levels reported better physical health. Social support from informal social networks, such as family members and friends/co-workers were found to have direct and significant effects on mothers' self-reported physical health and depressive symptoms.

In Malaysia, services are provided within a culture where support implies an act of charity, rather than being a right or entitlement. Some services and resources provided for children with a disability have poor quality, lack regulations, have limited availability, and are under-funded. Children with a disability enrolled in public schools do not use inclusive programs and teachers have limited professional training and qualifications to teach children with disabilities (Cooc, 2017).

Discussion

The results revealed that parents of children with disabilities had different pathways to get a better health outcome. Parents of a child with a disability often have negative perceptions, including feeling pessimistic, embarrassed, withdrawn and even rejecting the existence of such children. This may happen, particularly when the efforts made seem to be fruitless, and parents feel unable to educate and care for their children.

These results inform practitioners and local community stakeholders in developing programs to help families with children with disabilities. In light of the study results, community programs that promote help through informal social relationship networks, greater community engagement, and the reduction of affiliated stigma may be important ways to improve physical health and alleviate depressive symptoms among parents of children with disabilities. Thus, practitioners may consider parent's age, education, employment status, cultural backgrounds, and child age as screening tools to identify potential risk factors and the service needs to develop programs or services that meet their specific needs.

There are several factors that cause mental distress in parents who have children with disabilities. First, financial problems, the need for consultation, treatment, and purchasing equipment. Second, emotional problems, such as feelings of guilt, blaming each other, shame, and feelings of being rejected by other family members, parents are also facing issues such as changes in family goals and expectations, and negative views and stereotypes from society, neighbors and friends. Third, the issue of the need for intensive care for children with disabilities, often hinders the work, careers of parents, and some even give up work to care for their children. Finally, there is the issue related to the difficulty of finding adequate educational institutions that are willing to accept children with disabilities.

It is suggested parents who have children with disabilities become involved in parent-teacher conferences to be aware of and recognize the disabilities to support the child's development and learning. Parents are also encouraged to collaborate with teachers to reconsider the methods of assessing children to support their learning. For example, the conventional assessment method based on "what cannot be done" has several advantages such as setting goals for each child and making an appropriate intervention at the early stage (Abdullah et al., 2017). However, this method only indicates "what a child cannot do at the moment." As each child has his or her own pace of learning, "what a child cannot do at that moment" should not be interpreted as the same as "what a child will not be able to do in the future" (Park, 2020, p. 51). The appropriate assessment should align with "what a child will not be able to do in the future" (Author, 2005, p.55). Therefore, it is necessary to employ not only the assessment method based on "what cannot be done" but also other methods to evaluate children's abilities from a long-term perspective.

It is important for children to work towards achieving their goals even if they take a longer time than others. Professionals should understand such individual variability in developing skills and abilities are critical to help parents understand the disabilities and strategies to help and accommodate them at home. Understand the parents' cultural traditions, values, socio-economic status, educational backgrounds and expectations regarding their children are also critical to the help children with a disability. Furthermore, to consider the development and influence of technology and roles of other siblings with no disabilities are important as other factors. The level of discrimination tends to vary for each type of disability. For example, children with psychosocial or behavioral disability, such as hyperactive disorders, face greater stigma compared to those with physical disabilities (Abdullah et al, 2017; UNICEF, 2016). There is a lack of social acceptance for children with these impairments, even if they manage to enroll in mainstream schools (Islam, 2015). Parents' perceptions of children with disabilities determine parents' acceptance and the quality of care provided and these could affect children's development, social behavior skills, and adaptability.

In Malaysia, some of the language used to describe disability is quite derogatory such as "handicapped' and the assumption that having a disability implies a state of abnormality and dependency (Government of Malaysia, 2015). The term "special" which is typically used about children with disabilities, is starting to be recognized as potentially segregating and contributing to the overall experience of exclusion. Welfarist-based thinking is also pervasive, reflected in the language used to describe disability as a derogatory word meaning handicapped for example, is still widely used (Cooc, 2017; UNICEF, 2017).

- *1 Karma: The force produced by a person's actions in one life that influences what happens to them in future lives (in Buddhism, Hinduism, and some other religions).

-

References

- Abdullah, A., Hanafi R., & Hamdi, D. (2017). The rights of persons with disabilities in Malaysia: the underlying reasons for ineffectiveness of Persons with Disabilities Act 2008. International Journal for Studies on Children, Women, Elderly and Disabled, 1, 127-134

- Aminnudin, N.A. (2020). Ethnic differences and predictors of racial and religious discrimination among Malaysian Malay and Chinese. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1766737

- Bee, O, J., & Ahmad, Z, (2024). People of Malaysia. Encyclopedia of Britannica.

- Chonghui, L (2019). Over 10,000 special needs children enrolled in schools under zero reject policy. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/05/07/over-10000-special-needs-children-enrolled-in-schools-under-zero-reject-policy

- Cooc, N. (2017). Examining racial disparities in teacher perceptions of student disabilities. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education. 119 (7). https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811711900703.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia (2024). Sustainable development goals indicators. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r¼column/cone&menu_id¼bEdTaUR1ejcrZUhGQlFtRVI4TG93UT09..

- Disability Act (2008). The Americans with Disabilities Act: Amendments Act of 2008. https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/americans-disabilities-act-amendments-act-2008

- Doniger, w. &Gold, A.G. (2024). Hinduism. Encyclopedia of Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hinduism/Practice

- Feng, J. (2019). Cultural interpretations among Asian views of disability. Journal of Disability Studies, Student Paper.

- Government of Malaysia. (2015). Education Blueprint 2015-2025. https://www.um.edu.my/docs/um-magazine/4-executive-summary-pppm-2015-2025.pdf

- Government of Malaysia. (2008). Disability Act. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2022/11/Malaysia-Pwd-Act-2008.pdf

- Gowramma, I.P, Ganmei, E, & Behera, L (2021). Research in education of children with disabilities. Research Gate, Indian Educational Review, 56 (2), 1-92. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352559858_Research_in_Education_of_Children_with_Disabilities

- Hasnain, R, Shaikhm L. C., & Shanawani, H (2008). Disability and the Muslim Perspective: An Introduction for Rehabilitation and Health Care Providers. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Disability-and-the-Muslim-Perspective%3A-An-for-and-Hasnain-Shaikh/b5d291aeb8b566191fd6912503d0c4c63e9a43e6

- Hu, X. (2022). Chinese fathers of children with intellectual disabilities: Their perceptions of the child, family functioning, and their own needs for emotional support. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68 (2), 147-155. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20473869.2020.1716565

- Islam R., (2015). Rights of persons with disabilities and social exclusion in Malaysia, International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 5(2), 171-177.

- Malaysia Demographics Profile. https://www.indexmundi.com/malaysia/demographics_profile.html

- Park, E.R., Perez, G.K., Millstein, R.A. (2020). A virtual resiliency intervention promoting resiliency for parents of children with learning and attentional disabilities: A randomized pilot trial. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 39-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02815-3

- Saldana, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE

- Sukeri, B, & Othman, M. (2017). Barriers to unmet needs among mothers of children with disabilities in Kelantan, Malaysia: A qualitative study. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 12(5), 424-429.

- UNICEF (2019). 'Children Out of School - Malaysia: The Sabah Context', p 25. https://www.unicef.org/malaysia/media/896/file/Out%20of%20School%20Children.pdf 14

- UNICEF Malaysia (2016), Childhood disability in Malaysia: a study of knowledge, attitudes and practices. Malaysia. 25 Op cit, 85.

- UNICEF (2014). Children with disabilities in Malaysia: mapping the policies, programmes, interventions and stakeholders. UNICEF Malaysia.

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/

- World Health Organization (2007) The International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health for Children and Youth. WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Report on Disability (2011). World Report on Disability. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182

- Wu, F.H, (2002). Yellow. Basic Book.

- Yunus, S.M. (2005). Childcare practices in three Asian countries. International Journal of Early Childhood, 37(1), 39-56.

Sham'ah Md-Yunus

Sham'ah Md-Yunus