Quite a few daycare centers and kindergartens seem to have difficulties in dealing with children with special needs. This is especially true when it comes to children with developmental disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Asperger syndrome and so forth, due to the fact that their behavioral patterns are different from the children around them. What should be taken into consideration when dealing with children with developmental disorders and their parents? We interviewed Dr. Yoichi Sakakihara, professor of Ochanomizu University, who has addressed the issue of developmental disorder as a medical doctor.

Using "Diagnosis" Based on Correct Knowledge to Find an Appropriate Response

I think that, through their daily interactions, teachers at childcare and educational facilities realize that every child has his/her own differing needs. Based on their experience and knowledge, they must decide on the best way to deal with each child as an individual.

The way of thinking when dealing with children with special needs is basically the same. However, in dealing with them, it is necessary to carefully observe their needs since their behavioral patterns are different from the children around them. Furthermore, behavioral patterns vary significantly from child to child. For this reason, correct understanding about developmental disorder is crucial. You're more likely to find appropriate ways to respond if you can understand the reasons for a child's behavior. Children always have their own reasons for doing things.

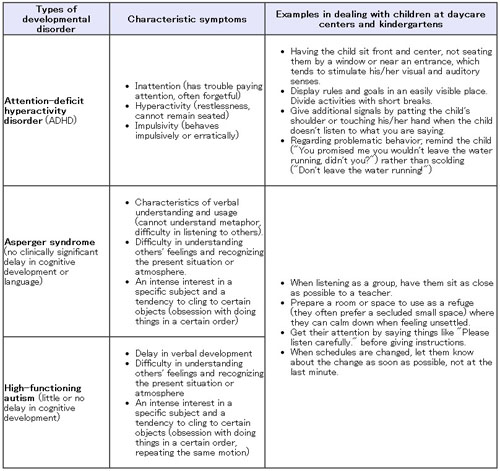

According to a survey conducted in 2002 by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), it was revealed that there is a possibility that 6.3% of children in normal classes have a developmental disorder. Developmental disorders include ADHD, LD, autism, Asperger syndrome and so forth. Each of these disorders have their own characteristic behavior. (See Table 1)

By deepening their knowledge concerning the behavior of children with a developmental disorder, teachers become able to "diagnose" such children. Diagnosis means, for example, working from the assumption that "it might be better to consider the possibility of ADHD since the child's behavior has shown characteristic symptoms." Bearing such a possibility in mind may lead the teacher to read up on developmental disorders in order to get some hints on how best to deal with the child. However, what should be kept in mind is that "diagnosis" is only a premise and completely different from labeling.

Rather than judging from an adult's perspective, try to see things from the child's point of view.

Regarding Developmental Disorders as Differences Rather than Diseases

Developmental disorders are innate and are not caused by bad parenting. However, children's behavior changes depending on how they are treated by the adults around them. A study was done to survey how the development of children with ADHD was influenced by the differences in the way they were treated by adults. It was found that continuous scolding is likely to worsen a child's behavior. On the contrary, accepting a child's feelings can gradually reduce problematic behavior.

What should be kept in mind above all else is not to take the attitude of trying to cure their disorder. Developmental disorders should be regarded as "differences" not as "something that needs to be cured." The problems are not with the children, but with the friction their behavior tends to cause with the people around them.

Seen in this light, we come to understand that the main point is in how to provide an environment in which the child causes less friction. The answer varies depending on the type of developmental disorder. For example, in the case of ADHD, problematic behavior can be reduced by having the child sit front and center, by not seating them by a window or near an entrance, which tends to stimulate his/her visual and auditory senses, and so forth.

Even when friction occurs, as the child had no intention of causing a problem in the first place, scolding the child without hearing his/her side of the story should be avoided.

Furthermore, it is also important to consider the viewpoint that friction can be reduced by adult intervention, not by leaving it to the children to work out on their own. When raised in an environment in which children can show their potential, they can build self-esteem and learn how to build relationships with other children. This leads to improving their characteristic behavior.

*Symptoms of learning difficulties (LD), difficulty in acquiring writing skills, calculation and so forth, are likely to appear after entering elementary school.

*There are some experts who consider Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism to be the same disorder since it is difficult to show consistent differences between the two except for a presence or absence of a delay in linguistic development.

Building a Trusting Relationship with Parents by Being Specific

Next, I would like to discuss how we should treat parents who have children with a developmental disorder.

In today's Japan, as a whole, the number of people who experience raising children is decreasing due to a falling birth rate. Compared to parents in the old days, it is natural that parents today are less likely to notice the possibility that their child might have a developmental disorder as they often have only one child and therefore cannot compare the child to a brother or sister. For this reason, the existence of teachers becomes more crucial as they see many children daily and have a kind of measure with which they can judge what a three-year-old child can normally be expected to be able to.

Since developmental disorder is a very sensitive issue, teachers have to take great care when conveying this possibility to parents. Even if a developmental disorder is suspected, be sure not to assertively state that, "Your child seems to have a developmental disorder, so I recommend that you take your child to a doctor." Doing so is highly likely to lead the parents to reacting defensively as they may feel that they have to carry the burden alone or worry that their child might be expelled from the daycare center/kindergarten. This will make future cooperation with the parents more difficult.

First of all, avoiding using the term "developmental disorder" and instead convey specific problems like "Your child has difficulty sitting still in a group", "He/she seems to have difficulty understanding teachers' instructions" and so forth. In order to get the parents to understand your concerns, give them the opportunity to see their child in class. If this is difficult to arrange, recording the child's behavior in class after getting permission from the parents is another possibility. Observing the actual situation could help persuade the parents to understand your concerns.

At the same time, explain specifically how you and your colleagues, the teachers, are dealing with the child and are fostering a favorable environment for him/her. After doing so, saying something like "In spite of our efforts, things don't seem to be improving with your child" could help communicate your concerns and efforts.

After taking these steps, you could then mention for the first time the possibility of a developmental disorder and recommend that they bring their child in for diagnosis. At the same time, it is very important to keep a cooperative stance by saying, "The reason I recommend seeing a doctor is that I would also like to know, as a teacher, how best to deal with your child." If time allows, you could offer to go to an expert with the parents. This might help ease the parents' tension and deepen mutual trust.

Acting as a Partner in Supporting a Child's Growth

In dealing with a child with developmental disorder and his/her parent, place importance on keeping a "counseling mind" that always shows a receptive attitude toward your clients. On that premise, it is necessary to have correct knowledge of developmental disorders. As I mentioned before, how children with a developmental disorder grow is significantly influenced by the differences in the way they are treated by the adults around them. Particularly during infancy, children are likely to cause problems due to their lack of social experiences. However, with continuous appropriate handling, they will be less likely to cause trouble by learning how to relate to others as they are growing.

Conveying this to the parent could be taken as both encouragement and a huge burden. I believe, by acting as a partner for the parent and showing your consistent attitude of wanting to support their child's growth, you can definitely ease their burden and help them to raise the child in a positive way.

To Everyone in the Field

I trust that you, the teacher, are making an effort to find your own way while dealing with children who need special care. Though I imagine it must be tough for you to make the time, please share each of your experiences during training courses. Sharing your experiences with your colleagues in this way will broaden your perspective on children and improve the way you deal with them. This will eventually lead to wholly improving the quality of child-rearing at your institute.

Yoichi Sakakihara

Yoichi Sakakihara