New Zealand has many types of early childhood education (ECE) services. Teacher-led services include kindergartens, education and care centres, and home-based education and care services. Parent-led services include playcentres, Kōhanga Reo, and playgroups (See Table 1). Although there are many types of ECE services, all ECE services are delivered through the implementation of a common early education curriculum called Te Whāriki*1. International studies on early childhood education in New Zealand focus on this curriculum. As its most important feature, this curriculum is not purpose-oriented but based on ideals consisting of four principles and five strands. "Te Whāriki," which means "mat" in Māori, one of New Zealand's official languages, considers the curriculum to be "a mat for every child" and is widely-used in many ECE services with varied educational philosophies and cultural backgrounds. Nowadays, Te Whāriki is becoming famous in Japan although its origin is not that well known. In this article, the origin of Te Whāriki, the features of Te Whāriki, and recent issues will be introduced.

| Teacher-Led | Education and care centres* | Generally, education and care centres are called daycares or pre-schools (These centres are similar to "hoikuen" in Japan). Montessori and Rudolph Steiner centres are also categorized here. Half of the teachers must hold a diploma in Teaching. These services usually charge fees. |

|---|---|---|

| Kindergartens* | Generally, they are called "community-based kindergartens". To lead the session, teachers are required to have qualifications. Kindergartens usually ask for donations and fees. Those with longer sessions charge higher fees but the charge is lower than at Education and Care Centres. | |

| Home-based education and care services | Home-based education and care services are services for small groups in a home setting. This service is supported by a registered teacher (co-ordinator) who supervises matters such as safety and the progress of education. This service usually charges fees. | |

| Parent-Led | Playcentres | Playcentres look like kindergartens but are run by parents (or caregivers) only. Parents' responsibility and role in education is very high, so parents are encouraged to attend Playcentre courses to organize sessions. Fees or donations are lower than teacher-led services. |

| Kōhanga Reo* | This service is for children and parents to build their knowledge of Māori language and culture. Kōhanga Reo has its own facility and is administered in the Māori language. Donations for food/fees are asked. | |

| Playgroups | Playgroups provide a place for children to play up to 4 hours per day. Parents and caregivers usually accompany children. (The children's program run by "jido-kan" in Japan is similar to the playgroups.) Most playgroup sessions are conducted in community halls or churches. | |

| Kōhungahunga | This type of playgroup helps children learn the Māori language and culture. The language it is conducted in depends on each playgroup. It may be in both English and Māori or entirely in the Māori language. | |

| Pacific Island Early Childhood Groups | This type of playgroup helps learning the Pacifica language and culture (eg: Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, Tuvalu and Fiji). The language it is conducted in depends on each playgroup; it may be in both English and a Pacifika language or entirely in one Pacifika language only. | |

| Others | Correspondence School | This service is one choice for children who live far away from early childhood education services or children who are ill or have a disability. The correspondence school teachers support parents in the conduct of activities or play. Educational materials such as books, puzzles and educational games can be borrowed. |

| Special Education | This is an additional service for children with special education needs until they go to school. The details depend on the children and inquiry basis. | |

| · This information is mostly taken from the Ministry of Education. · Children are not necessarily limited to only one service but may also avail themselves of a combination of services. · Fees vary widely within the same category services. Every child over 3 years is subsidized for 20 hours per week. Also, there are additional subsidies depending on the family's income. · ECE services with * have their own facility. | ||

The Origin of Te Whāriki

Until 1990, the quality of education at kindergartens was adequate in terms of teacher's qualifications and fees. At that time, other services were not qualified and subsidized *2. Generally, the kindergartens were established for children turning 3 years of age. However, most kindergartens used to hold a morning session for 4-year-old children and an afternoon session for 3-year-olds *3. They also ran sessions aligned with school terms which meant they had long holidays *4. This kindergarten system was not suitable for working parents. With the rise of the women's rights movement, the right to choose services, equal subsidies, and the quality of ECE became important issues. Moreover, there was a focus on increasing the attendance rate of Māori *5 and Pacific Islanders. Increasing numbers of migrant children in schools were also a concern. Coincidentally, every service delivered under the Department of Social Welfare was transferred to the Ministry of Education in 1986. Thus, there was a practical need to make a curriculum that could cover many services and philosophies together. It was during this period, sometime in 1990, that Te Whāriki had its beginnings. A national curriculum was needed but service providers were also concerned that the national curriculum would obliterate their independence and diversity. Margaret Carr, the project leader, together with other authors, tried to listen to all service providers. This became possible because of the Kōhanga Reo Trust *6 and Tamati Reedy's *8 corporations which accomplished the Māori immersion education *7 program. It took more than 6 years to complete Te Whāriki. The process of developing Te Whāriki was more bottom-up than top-down. In writing this section, May (2005) was mainly referenced but there are many academic articles regarding the development of Te Whāriki. This topic is also included in the document on Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996, p.17-18).

Some features of Te Whāriki

Te Whāriki has many unique features. In particular, three features of Te Whāriki are important to explain in order for Japanese people to understand this curriculum. Firstly, the term "curriculum" used in Te Whāriki has a more holistic and broader meaning than how it is generally used in Japan. This holistic meaning can be seen in the introduction of Te Whāriki which explains, "this curriculum is founded on the following aspirations for children: to grow up as competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body, and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society." Secondly, the central idea comes from the concept "empowerment *9" which was the most important topic among Māori people in 1996. Along with this, authors recognized that the empowerment of children is the most important issue not only for Māori but also for all children across New Zealand. Consequently, the four principles and the five strands were decided. The four principles are Empowerment, Holistic Development, Family and Community and Relationships while the five strands are Well-being, Belonging, Contribution, Communication and Exploration. The details are listed in the tables below. Te Whāriki establishes these principles and strands as a framework in which children can learn and develop within a sociocultural context. Thirdly, the curriculum respects diverse practices. It does not contain specific objectives for each age or stipulate educational content. It also respects educational philosophies such as Montessori education, Rudolph Steiner education, and Playcentre. In fact, these service providers provide education according to their own educational philosophy and use Te Whāriki as a curriculum at the same time. Children with special needs are also covered by Te Whāriki. Furthermore, Te Whāriki is a bicultural curriculum. The curriculum includes translated Māori language and Māori immersion curriculum which is mostly used at Kōhanga Reo.

| Empowerment | The early childhood curriculum empowers the child to learn and grow. |

| Holistic Development | The early childhood curriculum reflects the holistic way children learn and grow. |

| Family and Community | The wider world of family and community is an integral part of the early childhood curriculum. |

| Relationship | Children learn through responsive and reciprocal relationships with people, places, and things. |

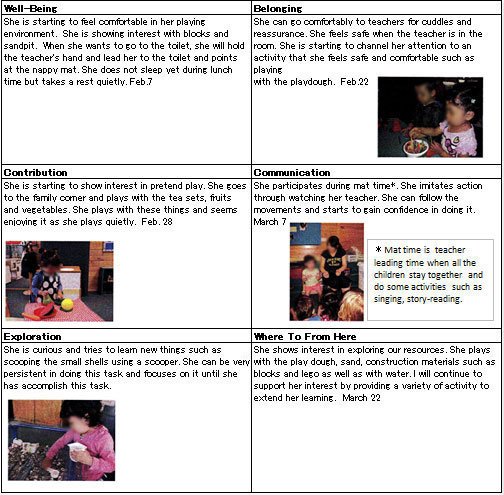

| Well-being | The health and well-being of the child are protected and nurtured. |

| Belonging | Children and their families feel a sense of belonging. |

| Contribution | Opportunities for learning are equitable, and each child's contribution is valued. |

| Communication | The languages and symbols of their own and other cultures are promoted and protected. |

| Exploration | The child learns through active exploration of the environment. |

Learning Assessment

How should a teacher assess children when the education is based on Te Whāriki? After 1996, a lot of research regarding assessment was encouraged and funded. The assessment method referred to as learning stories was finally introduced (Carr, 2001). More than 94% of ECE centres adopted learning stories in 2007 (Mitchell, 2008). This approach is not the traditional purpose-based assessment. It describes the children as they are. More of a narrative method, it is time consuming for teachers, but considered to be a very important tool for teachers and parents as part of a child's development. Recently, records are not only written but also recorded by digital camera as well. It is very common for the teacher to take photos in daily sessions. Learning stories are frequently used in teacher-led services. This method is not used as often in Kōhanga Reo Māori education.

Current Issues

People who know Te Whāriki are generally proud of it because of its democratic origin representing New Zealand's ideals. Internationally, Te Whāriki is highly evaluated as a leading curriculum by such organizations as the OECD. Also, teachers are positive about the curriculum because it respects teachers/services' development of their own educational practice. It has been already 17 years; most of the teachers working at ECE services now learned Te Whāriki at school. During this time, many migrants became ECE teachers to solve the teacher shortage issue and the proportion of migrant teachers is very high. Te Whāriki has attracted teachers who are migrants or the teachers whose colleagues are migrants.

On the other hand, there is also some criticism. For example, teacher's interpretations of Te Whāriki are too varied; the way of writing learning stories differs with each teacher; Te Whāriki becomes an excuse for some teachers since Te Whāriki does not require any specific result. Because the curriculum does not specify outcomes and practices, services and teacher's ability can be assumed to vary widely. Moreover, some recent research shows that despite the large amount of funding used in the ECE sector, there is no understanding of what New Zealand children are learning (Blaiklock, 2013). This criticism points out that there is not enough accountability in ECE. The recent rise in funding for ECE, which has doubled from 5 years ago, brought on this criticism. These criticisms may be difficult to deal with because, in the first place, Te Whāriki originally aimed to include diverse cultural backgrounds, educational philosophies, and many education services that already existed, but not to assess the result of each type of education service.

In June 2011, an independent ECE taskforce group *10 proposed many ideas regarding a vast range of topics including such matters as the quality of education and cost effectiveness to the Ministry of Education. This ECE taskforce was established by the Education Minister to review the ECE independently. In 2012, the Ministry of Education also unveiled Pathway to the Future *11 - a 10-year strategic plan for early childhood education. The content of this plan includes the subsidy system, effective implementation of curriculum, and assurance of the quality of ECE teachers. Researchers think these recent proposals will make New Zealand ECE more effective. Te Whāriki, being considered a leading curriculum in the world, faces recent issues such as market needs and a lack of accountability in New Zealand. The future direction of New Zealand early childhood education is now given more attention.

- *1 The extent to which Te Whāriki is used as a reference in daily education depends on each service provider.

- *2 The difficulty of obtaining quality education from a service provider other than a kindergarten is more obvious in the suburbs. In an urban area such as Auckland, owing to the competitive circumstance on ECE market, there are many private education providers which deliver high quality education.

- *3 Traditionally, kindergartens organize their services in this manner: 4-year-old children attend morning sessions and 3-year-old children attend afternoon sessions. Recently, more kindergartens offer all-day sessions, for example, from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. for children of all ages.

- *4 In New Zealand, the school year is divided into four school terms. Each term is 10 weeks long followed by a 2-week school holiday. The longest holiday is from the middle of December to the end of January.

- *5 Indigenous Polynesian people, who comprise 15% of the New Zealand population are called Māori. Māori people live modern lifestyles nowadays. However, Māori people have their own language and culture. The New Zealand government officially supports and respects Māori people in their policy. The Treaty of Waitangi is one of the bases of this political position. (Treaty of Waitangi: http://www.newzealand.com/us/feature/treaty-of-waitangi/). Māori people face many socioeconomic issues such as lower education, lower income, and higher unemployment rates.

- *6 Kōhangahanga is responsible for Kōhanga Reo.

http://www.kohanga.ac.nz/index.php?option=com_content&view=frontpage&Itemid=1 - *7 Immersion Education means that the education will be done in the target language. Thus, Māori Immersion Education means education is conducted in the Māori language.

- *8 The name "Te Whāriki" was also suggested by Tamaki Ready.

- *9 Generally, empowerment means giving minority people opportunities to gain self-confidence and live better in society. This concept is applied to early childhood education context: children are given opportunities to grow up as "competent and confident learners and communicators".

- *10 ECE taskforce group website: http://www.taskforce.ece.govt.nz/

- *11 Pathway to the Future website:

http://www.minedu.govt.nz/NZEducation/EducationPolicies/EarlyChildhood/

ECEStrategicPlan/PathwaysToTheFutureEnglishPlanAndTranslations.aspx - Blaiklock, K. (2013). What are children learning in early childhood education in New Zealand?. Vol 38.2, Australasian Journal of Early Childhood.

- Carr, M. (2001). Assessment in Early Childhood Settings-Learning Stories. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- May, H. (2002). Early Childhood Care and Education in Aotearoa-New Zealand: An overview of history, policy and curriculum. Vol 37 (No. 001) McGill Journal of Education.

- Ministry of Education (1996), Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Matauranga mō ng ā mokopuna o Aotearoa, Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

- Mitchell, L. (2008). Assessment practices and aspects of curriculum in early childhood education. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research

- Te One, S. (2013). Te Whāriki: Historical accounts and contemporary influences 1990-2012. Nuttall,J. Weaving Te Whāriki 2Nd Edition. Wellington: NZCER Press.