Social changes: Similarities to Japan

Germany and Japan face many of the same problems. Among them are both countries' struggles with the demographic challenges of rapid aging and low fertility. While the life-expectancy of people in Japan and Germany continues to increase, at the same time both countries see a decrease in children being born. In 2008, Japan's total fertility rate (the number of children a woman can expect to have in her lifetime) was 1.37, slightly up from the previous year. Germany's total fertility rate has seen a very similar development and stands at 1.37 (in 2007) as well.

Both countries' declining fertility rates are caused by multiple factors. One important factor is the delay of marriage and motherhood. Over time, German women are having children later than before. The changes for the age-ranges 25-29 and 35-39 are particularly telling. Whereas in 1994 37.4% of women gave birth at the age of 25-29, in the year 2004 the number fell to 27.7%. On the other hand, whereas in 1994 9.9% of new mothers were between the ages of 35 to 39, in 2004, their share doubled to 18.9%.

In 2004, married women living in Germany had their first child on average at the age of 29.6 years. The second child was born to mothers aged 31.3, and the third one at the age of 32.8 years. Yet these numbers vary by region, as married women living in the former territory of the Federal Republic, Western Germany, had their first and second children later than married women living in Eastern Germany, namely the new Länder and Berlin East.

Research shows that another major factor suppressing fertility is female employment, in case it is made difficult for women to combine labor force participation and childrearing. And that is the case for Japan as well as Germany, here particularly due to persisting traditional role models for mothers and fathers in German society, as well as certain family policies.

However, if institutionalized childcare, such as daycare centers (in Japan hoikuen, in Germany Kindertagesstätte, Krippe), are socially acceptable, economically affordable, readily available, as well as provide flexibility in care hours and a high level of quality of care, this negative correlation could be eased to a certain degree. Yet the presence or availability of institutionalized childcare in Germany is still comparatively limited, particularly for children under the age of 3, and has significant regional variations and numerous shortcomings.

Labor force participation of German mothers

A comparison of employment rates between women with and without children living in the household reveals clear distinctions in active labor participation. 75% of mothers with a child younger than age 4 are not in the paid labor force, thus women with children living in the household put clear restrictions on their professional activities up to the age of 40, and then, if they work, they are to a much higher percentage employed in part-time work than women without children. Whereas employed fathers do not usually reduce their working hours when they have minor children to be looked after, mother's employment varies significantly in relation to the age of their child. The younger the child, the more likely women are not to work. Similar to Japan, a large part of mothers living in Germany quit their jobs for a while at the time of childbirth, before returning to the job-market once the children are older.

Thus full-time employment rates for mothers are low. The majority of mothers are employed part-time. Overall, in the year 2005, 70% of all part-time work was performed by women in comparison to men and thus has remained a female domain (at least in Western Germany). Of the 33% of employed mothers of children under age 3, 63% work part-time.

In professions where part-time is not a viable option, Germany also sees an increasing number of women foregoing childbirth altogether. Nationwide about 25% of German women do so. Yet particularly in academia, the situation for women is severe. Here as many as 40% of all employed women forego having children. This is a clear sign that in Germany, having a career and children are still hard to reconcile.

Traditional roles and the taxation law

This situation is particularly aggravated by two factors: On the one hand it is the persistence of fairly "traditional" ideals of how mothers and fathers should allocate their time and roles in regards to how to balance work and family life. These favor the father as sole breadwinner, and the wife either to be a full-time housewife or, if needs be, part-time employed.

Concurrent with that, German family policies also support the traditional division of labor, thus usually meaning the male breadwinner model, which is similar to the situation in Japan. In both countries, the income tax system encourages married women's withdrawal from the labor market. In Germany, the so-called Ehegattensplitting (income splitting) only is financially beneficial for married couples with one partner having high, and the other partner having none or very low income. If the wife however has a full-time job in addition to the husband, the total family income is taxed at a significantly higher rate. In some cases, this could even mean a decrease in net income.

On the other hand, even if women would continue their employment, to a large part they just cannot, as there is no alternative for care-giving other than that by the parents. Daycare centers for children would be an alternative, to help women to remain in the workforce, but the number of daycare facilities, particularly for children under age 3, remains extremely limited.

Daycare in Germany: East-West differences

Overall, institutionalized childcare in Germany is primarily public. This is quite different to Japan, which not only has a large public, but also a large and growing private childcare market. Yet in regards to costs of care for the parents, daycare fees in Germany are charged like in Japan according to the household income of the parents and are relatively affordable.

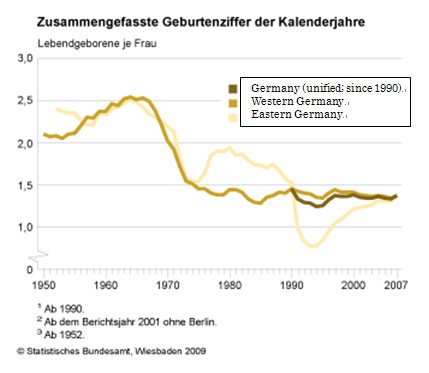

Since 1996, parents are legally entitled to institutionalized care for half a day for children ages 3 to 6 in a public daycare center. That is a step in the right direction, yet half-day care still does not allow for full-time employment of the main care-giving parent. The situation for children under age 3 is still lacking that provision. In that respect, it should be noted that it is difficult to talk about Germany as a whole. Even though Germany's reunification occurred 20 years ago, many differences between former Eastern and Western Germany remain quite visible - in social problems, employment rates, in population figures, in fertility rates (see figure 1), in the role of women and men in society and household, and in the system of institutionalized childcare (see figure 2).

Figure 1: Total fertility rate (live births per woman)

Source:

http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Content/

Statistiken/Bevoelkerung/AktuellGeburtenentwicklung,templateId=renderPrint.psml,

July 6, 2009.

As shown in figure 1, the TFR in Western Germany shows a similar development as Japan. In Eastern Germany, however, the birthrate had risen again in the mid 1970s. The sharp decline to a record low of 0.7 only a few years after the reunification in 1990 is unique and caused by the political and resulting social circumstances. By 2007, however, the fertility rate in Eastern Germany had rebounced to almost exactly the same level as in Western Germany.

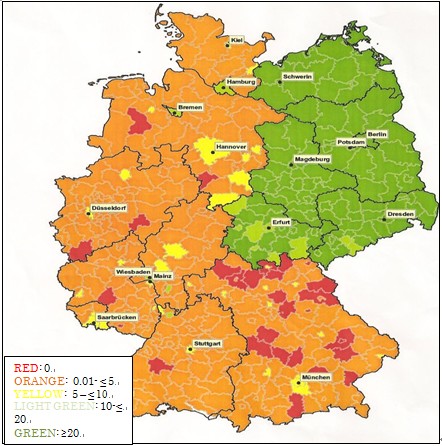

In regards to institutionalized childcare nationwide, there is space for only 22.1% of all children under the age of 3. However, when contrasting the situation in Western Germany with Eastern Germany, a significant difference becomes visible: Whereas in Eastern Germany, daycare space is available for 36.7% of all children under the age of 3, in Western Germany, it is only for 9.6% of all children (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, Oktober 2007. Zentrale Ergebnisse des Berichts der Bundesregierung, page 3; http://www.bmfsfj.de).

Figure 2: Daycare center distribution for children under the age of 3 in Germany (available spaces per 100 children under age 3)

Source:

Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder (2004): Kindertagesbetreuung regional 2002. Krippen-, Kindergärten- und Hort-plätze im Kreisvergleich, p. 18.

Shortcomings of the current daycare situation

As the above numbers show, the availability of daycare facilities in Germany, and particularly in Western Germany, is very limited. And in comparison, there are much less daycare facilities than in Japan. However, besides these quantitative shortcomings, there are further shortcomings to the system. Some of these concern the opening hours of the daycare centers:

| - | Daycare centers often close at 5 p.m., the latest by 6 p.m.. In Japan, extended hours past 7 p.m. for public and until 8 or 10 p.m. for private hoikuen are not a rarity. |

| - | About 50% of all daycare centers still close for lunch, which does not allow for any fulltime employment of the care-giving parent. |

| - | Half of all employed people in Germany work either on weekends, at night or as shift-workers. Daycare opening hours however are not flexible, and are neither open on weekends or at night. Also in Japan, shift-workers, though, have a hard time finding care and thus often have to turn from public to private daycare options to have their needs met. |

| - | A significant number of daycare facilities close over the summer for four to six weeks. Even though German vacation on average is significantly longer than standard vacation time in Japan, still German parents report the long closure over the summer as very difficult to organize in case both parents are employed. |

In regards to the quality of care, comparisons between Germany and Japan are difficult to make and naturally there is great variance. However, what can be said is that both in Japan and Germany, the profession of care-giver in daycare facilities used to be almost exclusively female. That however seems to be shifting in Japan, with the number of male care-givers increasing, more so in private, but also in public daycare. That is reported by Japanese parents as a positive aspect, as male care-givers provide role models for the children, substituting absent fathers due to long working hours.

New trends in policy making

In Japan, ever since 1990, policies were designed to increase daycare facilities (e.g. Angel Plan, etc.). In Germany, such policies have developed several years later, yet are similar in numerous aspects.

For a few years now, the Minister of Family, Senior Citizen, Women and Youth, Ursula von der Leyen, has made a particular effort to tackle the shortcomings of the daycare supply in Germany. Interestingly, she herself is a hard-working politician with a husband and seven (!) children.

Her efforts were successful in so far as that in 2007 the German government decided that the number of day-care spaces for children under the age of 3 is to triple by the year 2013, so to provide spaces for 35% of all children of that age-group. In addition, if a family is not putting their child into daycare, they are entitled to a cash payment of 150 Euro per month to support their at-home care-giving efforts. And beginning in 2013, parents can claim a legal right for a daycare space for their child under age 3 (the same already exists for children ages 3 to 6).

If these improvements to the daycare situation will prove to be successful, only time can tell.

For further information, please see also:

Germer, Andrea, Holthus, Barbara. 2008. Danjobyôdô to Work-life Balance - Doitsu ni okeru shakai-henka to shôshika mondai (Gender Inequalities and Work-life Balance: Social Change and Low Fertility in Germany). Tokyo: Deutsches Institut für Japanstudien / Stiftung D.G.I.A.. 36 p.

See also: http://www.dijtokyo.org/doc/WP0801_GenderIneq-Work-lifebalance.pdf

Related articles

- A Look at Working Mothers

- The Norwegian Man as a Father

- Basic Survey on Young Children's Daily Lives and Parents' Childrearing in Five East Asian Cities: Tokyo, Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei