| THEME | : | Aiming for a Society that Encourages a Positive Experience of Birth and Childrearing: Discussion Starting with the Concept of Doula |

| DATE | : | 14:30 -16:30 Thursday, September 25, 2014 |

| PLACE | : | Conference room, Shinjuku Sumitomo Sky Room |

| ORGANIZER | : | Child Research Net |

Introduction: What Is a "Doula"?

The term "doula" which means "an experienced woman who provides support to other women," originates from the ancient Greek word. It refers to a nonmedical person who assists a woman and her family before, during and after childbirth by providing physical and emotional support in various ways.

The concept of doula was introduced to Japan in 1977 by Dr. Noboru Kobayashi (professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, honorary director of CRN). In 2005, Dr. Rieko Fukuzawa (Kishi), who researched doulas in the United States, came across an article by Dr. Kobayashi while researching doulas in Japan. This was the start of regular features about doulas on the CRN website. In 2012, the Doula Japan Association was founded to train and certify postpartum doulas *1 and since then, the term "doula" has received more attention in the Japanese society. In 2014, a new series titled "Doula Case Studies" was started on the CRN Japanese website by Dr. Fukuzawa, which situated the concept of doulas in a wider context and focused on creating a society that encourages birth and childrearing as positive experiences.

This mini-symposium discussed on how we can realize a society that encourages women to have positive birth and parenting experiences based on the concept of doula.

[Topic 1] Recent Changes in the Social Environment Surrounding Childbirth in Japan (Seiko Mochida)

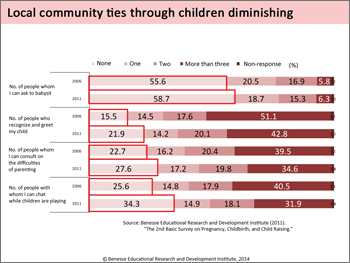

The average age of women giving birth to their first child has risen to over 30 years old in Japan today. The environment of mothering is changing and Japan is clearly evolving into a society of late marriage and childbirth. The following data is based on surveys conducted by Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute in 2006 and 2011 ("Basic Survey on Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Child Raising"). The study shows that only half of the respondents had experienced close contact with a baby before they became parents. As the results show in Figure 1, relationships in the local community that are mediated through children have become weaker. Traditional practices that support pregnancy and childbirth through family and community ties have been changing:

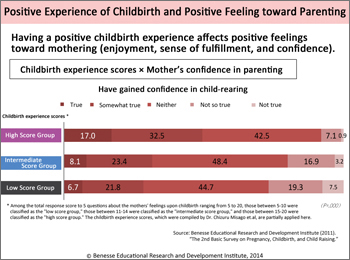

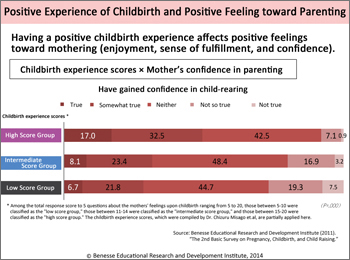

In terms of the relationship between the experience of childbirth and the positive feeling toward parenting, the survey shows that mothers who found childbirth to be a positive experience were likely to go on and have a sense of fulfillment, enjoyment and good confidence in parenting. On the contrary, those who were less satisfied with the childbirth experience tend to be less confident in parenting.

Mothers who are less satisfied with the childbirth experience tend to be less aware of the existing mental and physical consulting services for mothers and are less satisfied with those services when accessed. Therefore, it is likely that the necessary support has not reached those who need it most. In addition to improving the quality of extant support, it is also essential to consider establishing a system to inform mothers that such supportive services are available.

According to the above mentioned survey results, the mothers tend to be more isolated in current Japanese society than before. It is therefore essential for mothers to obtain mental and physical support during pregnancy, childbirth and early parenthood through a "doula-like" person.

[Topic 2] From the Perspective of Women's Childbirth Experiences: Do We Need a "Doula" System in Japan? (Chizuru Misago)

Hearing About "Doula" for the First Time in Brazil

The first time I heard the word "doula" was in Brazil in the 1990s. At that time I was working there to popularize midwifery. A doctor in a large public maternity hospital in Rio de Janeiro used the term. They were trying to introduce "doulas" into hospitals in Brazil, where there were no midwives. The word "doula" means "a person who stays with the mother during childbirth." At that time, 40% of public hospital deliveries were by Caesarian section, mainly taking place in hospitals with no midwives around. No matter how much the pregnant women suffered from pain, there was nobody who could accompany her to help during the delivery. It never occurred to anyone to support women in such a way, since there was no occupational equivalent to a midwife in Brazil.

However, as hospital staff came to agree that it was not good to leave pregnant women alone, the above-mentioned doctor asked experienced women who lived close by or specialists in physical exercise to give emotional and physical support to pregnant women in the hospital. They took on the role of "doulas."

Japanese Midwives Are Just Like Doulas

Do we need a "doula" system in Japan? If you let me jump to my conclusion, I have been thinking that we don't need one as we already have midwives here. As long as they can fulfill their essential role through their work, I think they already embrace the essence of "doulas."

In a country such as Japan where only 1% of mothers choose to give birth in a birthing home, it is quite rare that the midwife system has continued as an independent practice. There are many countries with a midwife system, but most do not allow midwives to practice independently. For example, the midwives in Finland are very active, being involved in most of the deliveries taking place in hospitals, however they are not allowed to assist deliveries without a doctor. This makes it difficult to expand their field of activities from the hospital to the local community, and as regular check-ups for pregnant women are the responsibility of public health nurses, they are unable to provide continuous care to pregnant women. On the other hand, birthing homes in Japan allow midwives to be deeply involved with pregnant women on an ongoing basis.

The doctors who visit Japanese birthing homes from developing countries are surprised to see how safe deliveries can take place even without medical intervention. They are also surprised to see both mothers and babies looking very happy there. The traditional way of Japanese childbirth seems to have many "doula-istic" aspects.

Doula as a Mature Woman

I would like to raise the topic of what it originally meant to accompany a woman during childbirth. A young ethnographer is doing some very interesting research on this. On a small remote island in Japan, there was a "menstruation hut" outside the village until the early 1970s. It was a hut where menstruating women stayed for a few days during their periods. At that time, menstruating woman was regarded as "foul," so they left home and stayed in the hut with other menstruating women for a couple of days during their periods. Responsibility for housework, including looking after children, was left to neighbors. This could be interpreted as "sexism," however, it could also be said that the segregation supported women once a month under the name of "foulness." Childbirth also took place in this hut.

On that island, when a girl was born, an unrelated kari-oya (a godmother-like parent) was appointed to support the girl throughout her life. The kari-oya accompanied her during childbirth as well, organizing a comfortable environment for her pregnant godchild, which allowed her to give birth with a sense of confidence in her own powers.

Through this custom, both the kari-oya and the supported girl were said to grow and mature. Everyone wants to be of some help to others. The woman who took the role of a kari-oya was someone who was capable of being attentive to others and ensuring a comfortable environment. The godchild was able to give birth, believing in herself, because she has trust in her godmother. The role of "doulas" can be interpreted as a person who "provides an environment for the mother," just like the kari-oya. In Japan, it is very inspiring to consider the concept of doula in terms of the role of a kari-oya.

*For more details on "kari-oya," please refer to the following article:

"Learning from Japan's Custom in Remote Islands: the Role of Social Parents at the Time of Childbirth"

http://www.childresearch.net/projects/birth_rate/2015_05.html

[Topic 3] The Future of Doulas in Japanese Society (Rieko Kishi Fukuzawa)

99% of Women Give Birth at Medical Institutions

Earlier in the discussion, it was mentioned that 1% of women in Japan gave birth in birthing homes, however this also underscores the reality that 99% of women give birth in hospitals or doctor-run clinics. In most hospitals, it is very difficult to offer continuous support to the mother as her care is fragmented and she is passed around various departments; for example, an outpatient department during pregnancy, a hospital ward during birth and the local community (such as a health nurse) after returning home. There is a serious and chronic shortage of maternity health care providers in Japan. Since non-medical care such as accompanying or encouraging the patient does not bring direct revenue to hospitals, it tends to be low in priority once staff becomes busy with other tasks. I worked in a hospital as a midwife and I admit that I could not provide enough non-medical support because of the time pressure of work.

When healthy pregnancy and childbirth are treated as an illness and without sufficient support to maximize the innate power of expectant mothers, the mother and her providers may tend to depend on medical interventions, instead. As a result, out of fear that something might go wrong, even if the expectant mother had wished to give birth naturally or to breastfeed, she tends to turn away from these natural instincts just to be on the safe side. This makes it difficult for women to believe in or exercise their innate power. Furthermore, social factors prioritize safety over the care desired by the expectant mother, which is caused by the reality that the obstetrician faces a greater chance of being subject to a medical lawsuit these days. These are the underlying reasons for why we need to have doulas in our society.

How Can We Develop Doula Support in Japan?

I would like to raise some current issues regarding doula support as an occupation which is popular overseas and also increasing on the rise in Japan. Firstly, can we convert doula support into money? I think this is a very difficult issue given that "doula" as an occupation is a way of "being," and often intangible and priceless. Once a doula-client relationship is established on the basis of a financial transaction, it might be difficult for the mother to pass on her appreciation of the doula's support and her repayment to the next generation for the support she received. Her feelings of the need to "pass it forward" may be thwarted by the financial arrangement.

Secondly, should the pregnant woman's family be expected to provide such support? Pregnancy is a very private event shared by the couple. At the same time, the baby is a treasure to society. In that sense, the child is a very public existence. As for my personal experience, I have received much warm support and helpful advice from strangers on a bus or in town who encouraged me with kind words such as "parenting is the biggest pleasure in life." In contrast, perhaps out of their kind concern to prepare me mentally, the advice of my own mother and experts was likely to be negative, telling me how difficult parenting was. Through such experiences, I feel that it is very meaningful to receive heartwarming support from complete strangers.

Finally, I would like to ask this question: Should doulas be certified and professionalized? Dr. Kobayashi says "a person who wants to be a doula is already a doula" and Dr. Misago has just defined a doula as a mature woman in her earlier discussion. If so, it would be very difficult to establish a certification exam to judge the competencies of doulas. However, certification could have some advantages; it would be more reassuring for clients to ask support from someone with a qualification, and for those who work as a doula, it would give them confidence in their work. However, I believe this should not make it more difficult for wonderful doulas who do not have the specific certification to work.

A Society Where Everyone Can Be a Doula

Ideally, I hope for a society where we all can be a doula. Since most births in Japan take place in medical institutions, I think there is a demand for doulas to support childbirth, in particular in medical settings. It seems that in Japan as well, the doula as an occupation is becoming increasingly necessary as an "interim measure" for the current social problems that we have. I would like to see a society in which those who presently work as doula are recognized and cherished as valuable.

[Panel Discussion] Aiming for a Society that Encourages Birth and Childrearing as Positive Experiences: Discussion Starting with the Concept of Doula

Coordinator: Yoichi Sakakihara (M.D., Ph.D., Director of CRN)

The panel discussion considered the three topics mentioned above from three perspectives regarding the support for "positive birth and childrearing": why support is necessary, what is necessary for this support and specific measures. Each speaker's remarks are summarized as follows.

To Reduce "Anxiety from Not Knowing"(Seiko Mochida)

Childbirth and parenting are likely to cause feelings of strong anxiety because they are something unknown and not experienced. For example, unmarried people tend to have a negative image of parenthood due to their lack of knowledge and experience. Although schools teach students about birth control, they do not teach much about becoming parents or provide essential information about pregnancy, childbirth and parenting to the young generation. In the context of the falling birth rate, it has become increasingly important to give essential information to both men and women of the young generation.

During pregnancy, providing detailed information about parenting to reduce the fear of expectant mothers leads to "positive childbirth." Furthermore, I believe that good emotional and physical care after childbirth and in the early period of child-raising will help mothers to be positive and happy throughout parenthood. Support based on a doula-like concept is essential as it will enhance information provision and intimate support throughout the maternal and perinatal periods.

Inspired by the System of "Kari-oya (godmother)" (Chizuru Misago)

The Japanese childbirth system is wonderful since it offers a wide range of choices from homebirth to birth in a university hospital. I think it is important for women to take responsibility for their own lives to make the most of this excellent system.

To make it happen, I want women to grasp something intuitively through their own physical experiences. Whether it is childbirth for one woman or breast-feeding for another, that physical experience has a huge impact that can completely turn their lives around.

To become a woman who is intuitive and proactive, I think we could take a hint from the idea of kari-oya, the parental role that provides continuous support to young women.

A Society which Both Supporters and the Supported Can Feel Confident (Rieko Kishi Fukuzawa)

Women in their perinatal periods are very sensitive. Therefore, it is very important for women to be in good and warm human relationships during this time.

The reality of the obstetric medical scene is that health care providers encounter difficulties in embodying those warm, human relationships with pregnant women and in providing sufficient non-medical support for mothers and their family members due to staff shortages and lack of time. As doulas can simultaneously help the pregnant mother and health care providers, introducing doulas into the medical settings is worth considering.

While the "doula" as a new occupation initially fulfills this non-medical support role, hopefully everyone in society can eventually help expectant mothers and their families as informal, natural occurring doulas. I would also like to add that anybody can be a doula and can gain personal maturity as a person by acting as a doula. In the critical periods of pregnancy, childbirth and early-parenting, I hope the mothers and those-to-be can find someone she can truly trust and be comfortable and open with as she seek ways to receive full support from society for her and her loving baby.

Conclusion: What We Need Now is Someone to Take the Role of Doula (kari-oya)

It has become more important to provide continuous support physically and emotionally to women during pregnancy and in childbirth. Many women tend to be isolated from the community at this time. Unfortunately, local community ties have diminished. Close relations with people who are not family members, in other words having someone who takes a role of doula (godmother), may enable a society that allows women to give birth and raise children with a sense of security. The mini-symposium came to a close with a proposal to raise awareness of specific measures to realize such a society.

*1 There are two types of doulas. One is a "birth doula" who supports pregnant and laboring women and their family members and the other is a "postpartum doula" who supports mothers and their family members in their postnatal period. The latter role is currently emerging in Japan.

Profiles

Chizuru Misago

Professor of Tsuda College, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Department of International and Cultural Studies. Specialized in epidemiology and maternal and child health studies. Born in Yamaguchi prefecture in 1958. Ph.D. in epidemiology from University of London. Various publications include "Onibabaka-suru-onnatachi (Women who become monsters)" (Kobunsha), "Tsuki-no-Koya (A moon hut)" (The Mainichi Newspaper Co., Ltd.), "Gokan wo Sodateru Omutsu-nashi Ikuji (Nurturing Five Senses Childrearing without Diaper)" (Shufunotomo Co., Ltd.), and "Onna wo Ikiru Kakugo (Being Prepared to Live as a Woman)" (Chukei Shuppan, Kadokawa Corporation) etc. Translation of "Pedagogy of the Obsessed" by Paulo Freire (Akishobo Inc.) and co-authored "Shintaichi (Body Intelligence)" (Kodansha Ltd.) with Tatsuru Uchida.

Rieko Kish Fukuzawa

Assistant Professor of the University of Tokyo, Division of Health Sciences and Nursing, Graduate School of Medicine. Practices as a nurse-midwife and lactation consultant. Areas of study include international comparative study on perinatal care and doula support. Being interested in doulas, studied at the University of Illinois in Chicago 2003-2009 and received her PhD in nursing science. Since 2005, has run the "Doula Laboratory" at CRN. Advisor of Doula Japan Association and a supervisor of the training course for prenatal/postnatal maternal helper at Nichii.

Yoichi Sakakihara

M.D., Ph.D., Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Sciences, Ochanomizu University; Director of Child Research Net, President of Japanese Society of Child Science. Specializes in pediatric neurology, developmental neurology, in particular, treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Asperger's syndrome and other developmental disorders, and neuroscience. Born in 1951. Graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, the University of Tokyo in 1976 and taught as an instructor in the Department of the Pediatrics before assuming current post.

Seiko Mochida

Research associate at Bennese Educational Research and Development Institute, Child Sciences and Parenting Research Offices. Major areas of study are "Basic Survey on Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Child Raising," "Report on the 'Waiting List for Nursery Schools' in Tokyo Metropolitan Area," "Report on People without Children," etc. Researches on changes in thinking, reality and the influences of environment-change caused by the increase in roles through having a family.