This qualitative study examined factors involved in contemporary Japanese university students' study abroad participation through the perspectives of study abroad (SA) administrators at Japanese universities. Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory was applied as a guiding framework in identifying various factors associated with Japanese students' decisions to study abroad. Five study abroad administrators working in Japanese universities participated in in-depth interviews regarding the immediate and distant factors that impact Japanese students' study abroad decisions, which included family, peers, school, business, education system, government policy, culture, and time. Based on the research findings, implications and recommendations for Japanese policy makers, university administers, and entities interested in recruiting Japanese students are discussed.

Results

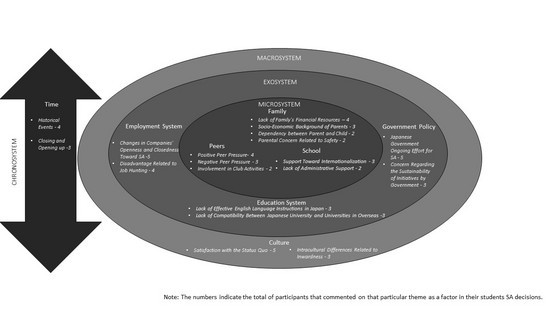

Two to four themes emerged in the immediate environment (family, peers, school) and distant environment (education system, employment system, government policy, culture, time) as factors in SA decisions. Figure 1 shows the themes that emerged from each environment level based on Bronfenbrenner's Systems Theory (1986)*1. The frequencies of each theme were included in the figure.

Figure 1. Themes related to Japanese university students SA decisions based on Bronfenbrenner's System's Theory (1986)

Family. The main themes that emerged related to the family factor were Lack of Family's Financial Resources, Socio-Economic Background of Parents, Dependency Between Parent and Child, and Parental Concern Related to Safety. Four participants identified family financial support as a primary factor that influenced students' SA decisions (Lack of Family's Financial Resources). Relatedly, Socio-Economic Background of Parents has influenced their perceptions toward their children's opportunities to SA. Rie*2, one of the five research participants, explained "The family environment is quite different. As you know, a social economic gap is increasing in Japan. There are a number of students at the poverty level which are struggling to get the money to attend universities.*3" The participants noted that scholarships and government support are crucial to ongoing efforts to encourage lower income families and rural families to consider SA.

Parents often discourage their children to participate in SA due to safety concerns (Parental Concern Related to Safety). For example, Ai shared that parents canceled trips in France and Thailand after recent terrorist incidents. Dependency Between Parent and Child often becomes an obstacle related to Japanese students' decision to SA. Kei discussed the Japanese mother-child closeness as the obstacle to SA in terms of helicopter parents: They are too anxious about the future success of their kids. It seems that they want to continue the connected relationship they had when their kids were younger. This pattern negatively affects students' attitudes and choices regarding SA in the form of strong control.

Peers. The main themes that emerged related to peer factors were coded as Positive Peer Pressure, Negative Peer Pressure, and Involvement in Club Activities. Four of the participants identified different ways that Positive Peer Pressure impacted Japanese students' SA decisions. For example, returning or current SA students have a positive impact by lowering psychological hurdles to SA participation (e.g., "Many students are willingly updating photos on SNS (Facebook, Instagram, and Line) during SA to share their experience with their friends." (Kei)). The participants also pointed to the dominant Japanese cultural pattern of conformity to group norms in their discussion of SA. Ai noted that if they join a community where everyone goes to SA and enjoys intercultural learning, they are easily motivated to SA. However, peer pressure can also manifest itself mainly in a strong tendency to conform to the normative progression to graduation and the job search (Negative Peer Pressure). The participants indicated that if students perceive that they will be left behind by their peers in the job search, this can serve as a strong deterrent to SA participation.

Involvement in Club Activities tied with the strong group mentality in Japan, which tends to discourage or distract students from participating in SA. Club activities are a big part of the life of university students in Japan. Consequently, even though students initially intended to SA, they ended up changing their minds (e.g., "My students sometimes come to me and say, 'Well, teacher, I am really enjoying my club activity, so I don't want to leave Japan.'" (Mari)).

School. The main themes that emerged related to school were coded as Support Toward Internationalization and Lack of Administrative Support. Three participants positively commented on the financial support for SA from higher administrators and/or alumni. For example, Rie talked about the scholarship for exchange students to SA that come from a university alumni group. At the same time, two participants also noted a Lack of Administrative Support for SA, due to institutional budget cuts or lack of financial resources. Ai expressed her frustration in relation to lack of staffing in the international office (e.g., "We always lack staff working for the university. A couple of the members tried to develop programs, but the staff complained because they cannot really handle all of the additional administrative work.").

Distant EnvironmentEducation system. The main themes that emerged related to the education system were coded as Lack of Effective English Language Instructions and Lack of Compatibility Between Japanese Universities and Universities in Overseas. Lack of Effective English Language Instructions was addressed by three participants, as Japanese students often lack confidence about their English proficiencies. Kei explained that "Generally in Japan, English teachers focus on the grammar, reading, and vocabulary that will be on the test, especially entrance exams. Practical uses of English are often ignored." Three participants, however, recognized the recent positive changes being implemented by the Japanese government, such as teaching English beginning in elementary school and an increase of English taught courses at university level.

Lack of Compatibility between Japanese Universities and Universities in Overseas often becomes an obstacle to students' decision to SA because it involves a risk of delayed graduation and additional educational expenses for students. Institutions sometimes failed to support students through their unwillingness to approve transfer credits for SA exchange programs. For example, Yuri noted that the differences in school schedules in Japan and universities overseas (such as starting early April vs. the end of August) discourage students from SA.

Employment system. The main themes that emerged related to the economic factor were coded as Changes in Companies' Openness and Closedness Toward SA, and Disadvantage Related to Job Hunting. All participants made comments related to Companies' Openness and Closedness Toward SA returnees. Four participants pointed to different ways that recent changes in business circumstances and hiring practices have begun to favor students who chose to SA. Mari stated that "Japanese companies are increasingly evaluating students to determine whether they are globally-ready or globally-minded. Maybe students will receive that kind of message from companies and be encouraged to go overseas." According to the four participants, however, inward-minded business attitudes are still very common in Japan, which often make it difficult for returning SA students to find a job. Kei explained, "When they employ new graduates, they commonly give priority to graduates from prestigious Japanese universities and those with personal connections rather than students with experiences and skills acquired by studying abroad." She further indicated her concerns as "...in extreme cases, students with SA experiences are negatively classified as individuals who failed to adjust to life in Japan... Returnees can be seen as too individualistic."

Disadvantage Related to Job Hunting was addressed by four participants as a reason for not doing SA. In Japan, students begin the process of looking for a job in their junior year and are typically hired immediately after graduation. Consequently, students who SA are sometimes excluded from this regimented process. This rigidly timed hiring schedule often discourages students from SA out of concern that their peers will gain an advantage over them in the job search. For example, Mari shared the experience of returning SA students as follows:

Most of the time, they must start job hunting activities quite soon after returning to Japan. Job hunting activities, norms, and customs are distinctly Japanese, so they really have to follow all the rituals of meeting people who are older and adjusting to the company culture.

Government policy. All of the participants acknowledged the positive contribution of the current government and private sector initiatives to send more Japanese students to SA (Japanese Government Ongoing Effort for SA). For example, Kei said, "The Japanese government has been doing really well as far as providing funding for universities, and sending more students out."

At the same time, three participants expressed Concern Regarding the Sustainability of Initiatives by the Government at universities, such as (1) strict rules and restrictions regarding the usage of the funds, (2) reductions/shortages of government funding after the initial approval, (3) instability of government funding based on political changes, and (4) unequal distribution of government funding (mostly distributed to top universities). Mari said that "We wrote all the proposals and action plans based on the funding that we were expected to receive, but the amount was reduced. We still need to keep our promises in our proposal, but that is impossible."

Culture. The two themes that emerged from the cultural factor were Satisfaction with the Status Quo and Intracultural Differences Related to Inwardness. The participants described the characteristics of contemporary Japanese students as a cultural pattern of satisfaction and complacency (Satisfaction with the Status Quo). Ai explained that her students used to be more adventurous, but they are now comfortable in their nice friend circle, and they just don't want to go out. Mari described her students as not being willing to take risks, face severe challenges, or change.

Three participants pointed out Intracultural Differences Related to Inwardness. In particular, two participants mentioned that female students are more willing to take the risk to SA if they have opportunities and resources when compared to male students. Mari described the two opposite patterns related to inwardness, "Some parts of Japanese societies are opening up quickly and really aggressively, but the rest of Japanese society is really closing and inward looking. I see the gap between those two different types of people."

Time. The main themes that emerged related to time and socio-historical conditions were coded as Historical Events and Closing and Opening up. Historical Events impact Japanese student openness to participating in SA. One feature of current historical events is the patterns of international tensions and terrorist acts, both internationally and in Japan's geographical region, East Asia. For example, at the time of this study, there was growing political tension between Japan and China, which resulted in a declining number of Japanese students doing SA in China, according to Ai. Yuri and Ai pointed to recent natural disasters that had occurred in Japan (e.g., Tohoku earthquake in 2011), and the subsequent economic difficulties the country experienced, as having a significant impact on SA participation.

Three participants commented on the particular historical context that students find themselves in and its impact on Japanese students' openness or closedness to participating in SA (Closing and Opening Up). One implicit example of the recurrence of this theme was Kei's description of the way that businesses in Japan were opening up due to the pressures of globalization, but also were struggling to adjust to these new realities and unable to change some of their traditional practices to create a welcoming environment for returning SA students. Yuri explained that the institutions are trending toward globalization, which subsequently affects SA trends as follows:

Our students see changing patterns in academic culture. We have more international scholars than before, and many professors go to international conferences and have international collaborations. These influence students to think about the importance of overseas experiences.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the factors that impact Japanese university students' decisions to SA from the perspectives of Japanese SA administrators through in-depth interviews. Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems (1986) was used to analyze multiple immediate and distant environmental factors that may influence Japanese students' SA decisions. As found in previous studies (e.g., Asano & Yano, 2009; Lassegard, 2013, Ota, 2013), the current study also identified a wide variety of environmental factors associated with contemporary Japanese students' choice to SA, such as the lack of financial resources, Japanese university schedules and curriculum, and the lack of English language skills. Our study specifically identified mixed views regarding some of the key issues affecting contemporary Japanese students' decisions to SA: (1) Japanese corporate hiring practices and business culture, (2) Japanese students' inwardness, (3) Japanese government internationalization initiatives, and (4) financial barriers to SA. Furthermore, our findings suggested an association between Japanese cultural patterns and students' SA decisions: (1) conformity and harmonious relations and (2) dependency between parent and child. Based on the findings of this study, we also discuss research implications for a variety of constituents, which include policymakers and university administrators in Japan, admissions and recruiting personnel at universities outside of Japan, and SA researchers.

In our study, Japanese corporate hiring practices and business culture was referenced as an obstacle for Japanese students' decision to SA, which was also identified in previous research (Asaoka & Yano, 2009; Lassegard, 2013). The responses from the participants revealed concerns related to the timing of the job search, the lack of enthusiasm in hiring students with SA experience, and delays in graduation. However, the participants also noted an increase in the global mindset of some large Japanese corporations, which might influence the vision of life trajectories for contemporary students. Along with globalization, Japanese companies recently started underscoring the importance of diversity management (Tominaga, 2016). Future research may benefit from exploring the global mindset of Japanese companies in relation to the recent emphasis on diversity.

Our findings support previous literature suggesting that Japanese students' satisfaction with the status quo and lack of confidence and initiative are often a hindrance to SA (Lassegard, 2013; Ota, 2013). As pointed out by Ota, our study also found two opposite spectrums of Japanese youths concerning inwardness - a group that is strongly orientated toward SA and a group with a weak orientation toward SA. Female university students appear to be more open to SA compared to male counterparts. Japanese female students' strong aspiration toward internationalization was also found in a recent study of Japanese university students (Kawano, 2013). In relation to this notion, future researchers may find it profitable to analyze the benefits of SA, paying specific attention to career trajectory differences between male and female students. According to the World Economic Forum (2018), Japan has the worst gender gap, next to South Korea, among all industrial nations.

Most of the participants in this study agree that the recent increase in SA participation is due in part to the ongoing Japanese government internationalization initiatives. Some participants did express concerns, however, about the sustainability of these programs when and if this support comes to an end. In addition, as addressed by Rappleye and Vickers (2015), concerns related to the increasing workload of faculty and international officers as a result of this political effort were expressed by some of the participants. This finding suggests the importance of prioritizing international endeavors at the institutional level and adjusting the budget in a way that will maintain programs that begin with an infusion of resources initially provided by the central government and a recognition of the need for adequate staffing.

Regarding the financial barriers, the current study found increasing economic disparities between Japanese students. Our study indicated that the Japanese international affairs' administrators perceived and reported a significant difference in family incomes, which made it difficult for low-income and/or rural families to pay for SA. In addition, there was a difference in career trajectory between the wealthy (predominantly urban dwellers) and poorer, rural Japanese students. Students from rural areas see themselves in careers that do not necessarily reward those with international experience, while students from urban areas, especially those attending top-tier universities, perceive the benefits of working in global industries and the rewards of international experience. This finding has implications for policymakers. Based on these findings the government should consider providing more Tobitate scholarships (the individual MEXT scholarships funded through a private/government partnership for students interested in studying abroad) to individual students at a variety of institutions, especially students from low income families, rather than funds for top-tier targeted institutions.

The Japanese cultural pattern of conformity and harmonious relations (Nakai, 1980) was also identified in this study. Along with parental expectations, students' SA choices were often related to the norms of the groups that they associated with (peer pressures) and their immersive involvement in school clubs. This finding coincides with results of a cross-cultural study of Japanese university students (Tsuboi, 2013). Compared to university students in other Eastern Asian countries, Japanese students are mostly categorized as "collegiate" types who tend to enjoy social life on campus more than academic achievement. It would seem helpful and important for SA administrators to consider different ways that they can take advantage of peer influence and design programs that take this dynamic into account. Two ways to do this would be to work directly with student clubs to design SA programs and make sure institutions take full advantage of returning students to expose current students to the benefits of SA.

Another cultural pattern found in this study was the dependent relationship between parent and child in Japan. Historically, beliefs about cultivating closeness between parent and child have been emphasized in Japanese parenting, which is believed to be a precursor for academic success in Japan (Azuma, 1994). The pattern of contemporary Japanese parents and children, revealed in this study, is a desire to remain dependent and an experience of separation anxiety when considering SA. Although helicopter parents who pay extremely close attention to a child's academic experience also exist in the West, Japanese parenting may be slightly different because children also prefer to remain dependent. Rather than resisting parental involvement as an intrusion into the student's lives and as an obstacle, SA administers may need to consider creative ways that they can persuade parents of the value of SA and team up with them in their efforts to convince students to SA.

Conclusion

Several limitations of this study should be kept in mind. First, the sample was small and not random. As mentioned earlier, the lack of staffing at international offices in Japanese higher education made it difficult to recruit participants. Some of the SA administrators are also teaching faculty, along with responsibilities related to SA. This made it particularly difficult to spare time for in-depth interviews. Second, all but one of the participants were from top-tier universities. The findings of this research might have been different if the participants had been from universities with lower financial resources, prestige, and support from the Japanese government.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, this was one of the few studies that analyzed the factors associated with Japanese students' decision to SA from the perspective of professionals who promote, encourage, and support student decisions to SA. In addition, the participants' bi-cultural experience (Japan and the West) contributed to their ability to critically evaluate the characteristics of current Japanese university students as well as on-going globalization efforts by the Japanese government, corporations, and higher education institutions through an implicit comparative lens. Further research is needed to develop effective strategies for encouraging Japanese students to SA through an increase in sample size and by systematically recruiting the SA administrators from a wide range of regions and levels. Such efforts not only extend our understanding of globalization in Japan but can also inform policy and practice in ways that will encourage more SA participation in other nations.

- *1 We excluded the question related to Mesosystem from our analyses because none of the participants had much to say.

- *2 See article 1. We used fake names to protect the participants' identities.

- *3 The English grammar of the interviewees was corrected by the first author.

References

- Asaoka, T., & Yano, J. (2009). The Contribution of "Study Abroad" Programs to Japanese Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13, 174-188. doi:10.1177/1028315308330848

- Azuma, H. (1994). Nihonjin no shitsuke to Kyoiku [Japanese ways of education and discipline]. Tokyo: Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723-742.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723 - Kawano, Y. (2013). Nihonjin gakusei no kokusai sikousei [Global orientation of Japanese students]. In M. Yokota & A. Kobayashi, Internationalization of Japanese universities and the international mindset of Japanese students (pp. 157-178). Tokyo: Gakubunsya

- Lassegard, J. P. (2013). Student perspectives on international education: An examination into the decline of Japanese studying abroad. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 33, 365-379.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2013.807774 - Nakai, K. W. (1980). The naturalization of Confucianism in Tokugawa Japan: The problem of Sinocentrism. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 40, 157-199. doi: 10.2307/2718919

- Ota, H. (2013). Nihonjin gakusei no uchimuki shikou saikou [Rethinking of Japanese students' inwardness]. In M. Yokota & A. Kobayashi, Internationalization of Japanese universities and the international mindset of Japanese students (pp. 67-93). Tokyo: Gakubunsya

- Rappleye, J., & Vickers, E. (2015, November 6). Can Japanese universities really become Super Global? Retrieved from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20151103154757426

- Tominaga, T. (2016, March 25). Japan urged to embrace diversity management as working population shrinks. The Japan Times, Retrievevd from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/03/25/business/japan-urged-embrace-diversity-management-working-population-shrinks/#.Wxl9u0gvw2x

- Tsuboi, K. (2013). Nihonno daigaku to daigakusei bunka [Japanese universities and university culture]. In M. Yokota & A. Kobayashi, Internationalization of Japanese universities and the international mindset of Japanese students (pp. 39-66). Tokyo: Gakubunsya

- World Economic Forum (2018). Global gender gap report. Retrieved from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf

| | 1 | 2 | |

Richard Porter

Richard Porter Noriko Porter

Noriko Porter