Key words: American soldiers, children, cultural differences, English teacher, friendships and love, Japanese mom, Keisen Christian Service Club, Keisen Jogakuen, Korean War, Manchurian repatriates, Marlene Ritchie, Pied Piper, resilience, rudimentary Japanese, Tokyo, Ueno children, Ueno Social Centre, vanishing differences, Yokohama Harbour

"What was it like?" I'm asked by friends when they hear that I lived in Tokyo from 1950 to 1953. It must seem like ancient times to them. Tokyo was still rebuilding after the incendiary bombings; there were shortages of everything; rice was rationed. I remember that classrooms at Keisen Jogakuen where I taught English had pot-belly stoves installed for the cold month of January, and each room received one bucket of coal a day to heat the room. The first year junior high school girls didn't know how to build a fire, and their rooms were dense with smoke so that the sliding windows had to be left completely open. At least by lunchtime the smoldering coal had warmed the stack of obento (lunch) boxes on the top of the stove.

I arrived in early September, 1950 to the Isshiki family home. Joann, another American girl who was finishing her three-year term of English teaching, and I lived on the second floor, and the family lived on the first floor. Having been one of Michi Kawai's first pupils during the founding years of Keisen Jogakuen, Yuri Isshiki and her husband were consummate supporters of the school and frequently looked after foreign teachers. The house was a tudor-style mansion hidden behind a high brick wall and accessible by car or on foot when a ponderous iron gate opened to a circular driveway past a covered stoop, which admitted people to the brick house.

The Korean War had begun two months earlier. Our passenger liner, the S.S. President Wilson, couldn't dock in Yokohama Harbour because every slip was occupied with ships being loaded with supplies or soldiers headed to Korea. We had to descend down a metal ladder to barges that took us to a hanger where we waited for our baggage. From the doorway we saw loads of American GIs waving to us from the beds of the trucks. We must have made them think of home, because when they saw us foreign teachers they called, "Where are you from?" or "Hello, hello. Are you from Iowa?" They were just boys, younger than me. Their eyes were wide with apprehension. My insides churned. Oh, oh, what was about to happen to them? I didn't want to look at their faces. I wanted to shrink inside myself to escape picturing each boy facing the North Korean firing line. Again I asked myself what war was about. Did young men have to die whenever there was a conflict between nations? Couldn't we find a way to accommodate our differences, compromise or just be tolerant of unfamiliar customs and beliefs? Those thoughts motivated me to go to Japan at the age of twenty-two, only five years after the end of the Pacific War. I grew up in a rural Ohio town of 490 inhabitants. I had never seen a Japanese person--only knew about Japan from newsreels and articles, but it had seemed to me that if I got to know a Japanese person, I would find their culture interesting, or at least be able to accommodate to different ways, and we most certainly wouldn't want to take up guns and kill each other. Having graduated from university and taught for one year, I went to Japan to teach and to test my theory. I intended to write home about the Japanese people I met, and I would show pictures and talk to my students about my relatives and friends back home.

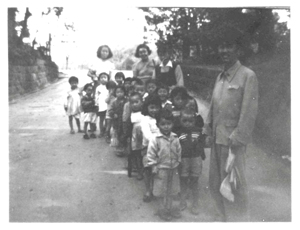

Children in front of Ueno Social Centre

When I arrived at my billet, I was received warmly by Mrs. Isshiki. She was more than a landlady; she was like my Japanese mom for which I am grateful. She taught me how to behave in this new culture: never eat while walking along the street; Japanese don't bathe in the tub, please wash first and then step into the hot ofuro; always return the following day to thank families who invited you to dinner; wear a mask when you have a cold; get under a desk or stand in a doorway when there is an earthquake; peel an apple before eating it. From her example I learned that I should sit with my knees together and never cross my foot over my knee. When I used my newly acquired word benjo for the word toilet, she corrected me. I discovered that there were words that only men and boys should use. There was much to learn, and I slipped up several times. Once when I was entertaining guests in our Japanese tatami (mat) room, I decided to seat the guests at the table facing the tokonoma where they could look directly at the alcove with the landscape scroll, but when Mrs. Isshiki looked in to see how I was doing as a hostess, she was horrified and hurriedly explained that she hadn't taught me that guests should be seated as close to the tokonoma as possible with their backs to this main attraction of the room. She kept her eye on me in a loving way and made an obento lunch for me to take on school outings--for Girls' Festival, a lunch comprised of foods coloured pink and green in keeping with the colours used at parties during this festival.

I used my rudimentary Japanese to shop at the market along the narrow Kyodo street. "Oishii sakana kudasai," I'd ask the fish monger for a delicious fish, and he'd suck through his teeth, scratch his head and whisper to himself in Japanese that he wondered what fish foreigners liked. At the butcher shop I might have to wait until a dead pig was unloaded from the bicycle that delivered the stiff carcass, and then to buy hamburger I'd ask, "Hiki niku hyaku mai kudasai" meaning the ground meat 100 weight please. On these shopping expeditions children would appear from out of nowhere. Little girls stopped jumping rope to join me, and in no time six or ten kids were grabbing for my hands or hanging onto my arms. Those children may have regarded me as an anomaly, but their natural curiosity was uninhibited. They felt no prejudice toward someone who looked different. It was like being the Pied Piper walking down the Kyodo street with a group of kids in my wake. Some would put their cheeks against my hairy arm and say. "Yawarakai" (soft). One little girl asked whether I was a sister or an aunt. I knew she was trying to figure out my age, since there are different words for a girl and for a woman old enough to be an aunt. In Japanese I told her that I was probably an aunt. One day after dozens and dozens of walks and talks, one little girl asked if I had a mother. To confirm that indeed I had a mother, I said, "Hai Okasan imasu." The little girl looked perplexed and asked in Japanese, "Well, how do you talk to her?" My Japanese, though child-like, sufficed so that she was comfortable talking to me, and we'd been together so many times that she forgot that I was from a different culture and spoke another language. Our differences had vanished.

I'd go with the Keisen girls who belonged to the Christian Service Club. We cleaned the home of a young laborer, a widower who was raising three children on his own. The mother's ashes resided in a jar sitting in the corner so that there was room for a table in the single room over a shop, which was their living quarter. One day we took the two younger children, a girl and boy age four and five, downtown to give them an adventure. The older son, age twelve or thirteen, was apprenticed to the bicycle repairman and had to work. We took the train and then an escalator to the top of a department store where there was a small zoo. We lifted them one by one to sit on a small elephant, talked to the monkeys and petted and observed other animals. Then we gave them money to buy souvenirs. They each bought cakes to take to their father and brother who couldn't come. As we approached their home, I asked what had been the most interesting thing we'd done. Both youngsters agreed that the train ride took first place, the escalator ride second and the elevator ride third. I was amazed. It just goes to show that when you stimulate children you can't know what the children will learn from the experience. Remembering that day makes me smile.

Group out for a walk; Returning to Ueno Park

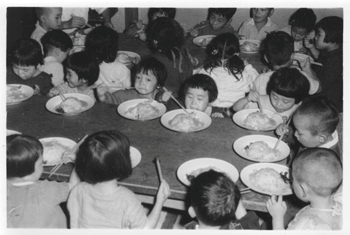

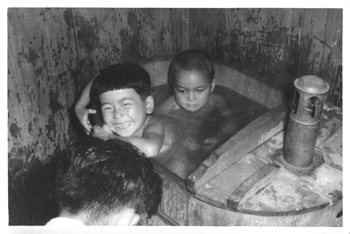

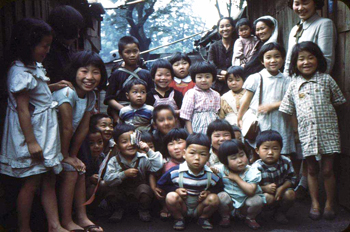

I joined the Keisen Service Club girls on Saturday visits to meet families squatting in Ueno Park. Those people had been repatriated from Manchuria and lived in shacks made of crates, pieces of corrugated metal and canvas. Some university boys had rented a house in the neighbourhood. They lived there and tutored the children who couldn't attend Japanese public schools, because they had no legal address. On Saturdays the house was used as a Social Centre to feed and bathe the little ones who couldn't use public baths. Keisen girls had a turn one Saturday a month. When meeting in the park, we would distribute day-old bread to families who had had nothing to eat the day before, and then we would walk with the younger children to the centre. Keisen girls would cook a meal--a stew and rice, while other volunteers would bathe each child and dunk them into the ofuro. I liked the job of helping with the baths. I remember the boy who took his towel, held it shoulder high and raced naked around the room like he was a flying Superman. And I remember the day that one of the volunteer girls, who worked at a toy factory, brought celluloid cupie dolls for each child. Afterwards, the walk back to Ueno Park was tranquilly silent. Each child, boys included, cuddled his or her doll wrapped in a shirt tail or the skirt of a dress as they trudged home with a doll of their own to love. Those children taught me resilience, that there was joy in everyday things, and that we all need love.

Ueno children eating

Bath time for Ueno children

In the meantime, my family members in the U.S. still remembered the war and distrusted the Japanese; however as they met my Japanese friends who visited America, they began to write that Mr. K reminded them of so and so, and when my sister took Yasuko Takahashi home from Ohio University for spring holiday, and Yasuko combed my grandmother's hair and helped my mother in the kitchen, they said it was like having me back home. I knew that their prejudice had vanished.

Since those years of living in Japan I have come to realize that there are injustices and oppressive regimes in the world, leaders who are bullies, and I realize that there is still a need for armies to stop a massacre and end injustices and torture perpetuated by the power-hungry, but for mature nations and on the home front, I believe that my theory is true. We do learn to understand, sometimes accept or at least to accommodate people living in our neighbourhoods who come from different cultures, and the connection enriches our lives. Our differences fade, friendships and love springs from the associations. We just need to multiply the contacts between people of different cultures millions of times. Often it's the children who bridge the differences first.

Conclusion

My experiences while living in Japan showed me that unless taught differently, children can be uninhibited when meeting a person from a different culture. They are curious, friendly and tolerant of language mistakes. Children are resilient. It is often the children who bridge our differences first and lead to tolerance or understanding, friendship and love between peoples from different ways of living.

Assembling in Ueno Park for walk to centre