Taxonomy of Bilingualism

- 1. Levels of Bilingualism > the Individual Level

- 2. Family and Societal Levels of Bilingualism

- 3. School and Academic Levels of Bilingualism (This paper)

Introduction

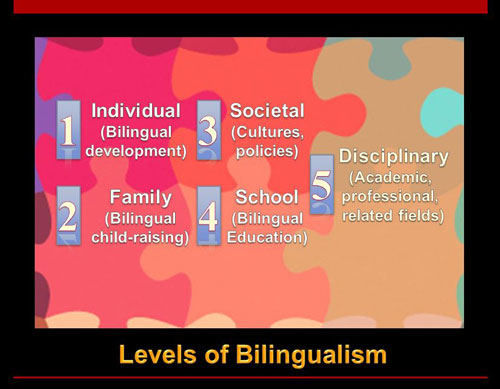

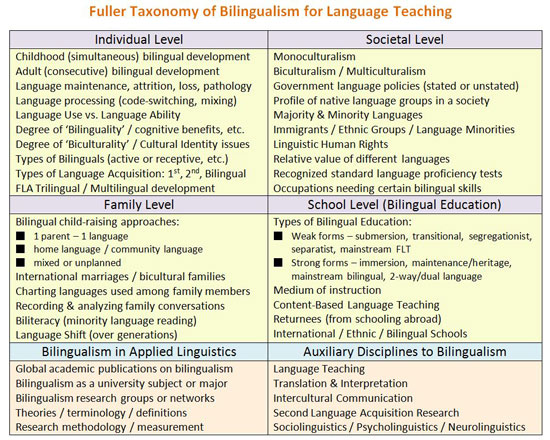

This article concludes the taxonomy of bilingualism, with the various phenomena of bilingualism classified by the author into five levels as in Chart 1 below. The focus of the first article was on the Individual Level, summarizing the items under that category in Chart 2 below. The second article continued similarly with the items under the Family Level and the Societal Level. This article summarizes basic issues at the School Level (Bilingual Education) and then introduces the Disciplinary Level, a fifth level where the four naturally occurring levels become a subject of academic and professional study.

Bilingualism at the School Level (Bilingual Education)

Bilingualism at the school level refers mainly to bilingual education, which should not be confused with bilingual child-raising at the Family Level. Bilingual Education in turn has many types, listed under the School Level in Chart 2 above according to Baker (2006, pp. 213-225). The various types of bilingual education in the world reflect the role of different languages in each society and the purposes, decided at the government or local level, that languages serve in their educational system and society. An earlier series analyzed in more detail the purposes that languages serve in education (McCarty, 2012a) and the corresponding types of bilingual education that result (McCarty, 2012b). Then cases of bilingualism around the world were presented, with a method to use in university classes for students to analyze the type of bilingual education in any educational situation in the world (McCarty, 2012c). Without repeating the earlier series, this section goes over some of the basic issues of languages in contact at the school level.

Bilingual education generally means teaching in two languages to some extent. While most school systems eventually offer foreign or minority languages if not bilingual education, a key issue is always the medium of instruction, the language in which courses are taught. The medium of instruction often serves to maintain the power of the dominant language and its native speakers in a society. Victims of such power structures include both language minority students and majority children who study foreign languages in their own native language belatedly and ineffectively. By contrast, in some regions of the world, effective bilingual education programs partly flip the medium of instruction of regular content courses to a target language that needs more use to develop than the dominant language does. Since balanced input and interaction in two languages are the most effective way for learners to become bilingual, whether in school or elsewhere, the weaker language normally needs more support and active use.

The proof of effectiveness of a bilingual program lies in the extent to which the students become or continue to be bilingual as a direct result of the curriculum. Developing the dominant language of a society takes less schooling than developing a second language. Thus the extent to which the medium of instruction is the target or weaker language tends to determine bilingual learner outcomes more than any other factor. Weak forms can be accepted as types of bilingual education mainly in the sense that having one dominant and one weaker language is a type of bilingualism. If students are bilingual despite the curriculum, because of using a minority language at home, then the school system cannot claim to be implementing bilingual education. Nor would international schools be practicing bilingual education if they taught in only one language, strictly speaking. But such schools are not compulsory and may be part of a bilingual strategy to add English or another international language on top of the home language. In any case, classes in both languages to an extent at international schools would more likely result in a strong form of bilingual education for children.

Continuing with the items in Chart 2 above under the School Level, there are many types of second and foreign language instruction that could be considered weak forms or not bilingual education at all. English or other languages for special or academic purposes could be considered bilingual education if such classes were taught in the target language or formed a significant part of the curriculum. Similarly, the difference between bilingual education and content-based foreign language teaching, where regular subjects are taught in a target language, is usually that in the latter case students simply cannot take enough such courses to become bilingual. Whereas, one of the strong forms of bilingual education, immersion, is defined as 50% or more of the curriculum being taught in the students' second language (Genesee, cited by Bostwick, 2004). Content-based foreign language teaching in half of all classes or more would therefore cross over into immersion bilingual education. Like bilingualism at the individual level, in education it is also a matter of degree.

While Chart 2 above does not mention specific languages, there are still items that attract particular attention in Japan. Returnees from schooling abroad present a dilemma of their having missed some of the native language and cultural influences of the standard national curriculum, making them different to an extent from mainstream students. It is difficult for traditionalists to appreciate that returnees also represent an opportunity for the nation's future with their linguistic resources and cosmopolitanism. As a result, catching up in the native language tends to be considered more important than maintaining or developing the second language of returnees, so the value gained from their experience abroad can be diminished or lost along with their bilingual skills. Returnees are prized, however, by universities that specialize in foreign languages, so returnees have an advantage in entering prestigious universities. While speakers of international languages have a positive image, there is yet little recognition that individuals can still be Japanese if they admit to such uncommon attributes as being bilingual and bicultural.

Besides the types of methods or approaches to languages in education, there are corresponding types of schools, the last item in Chart 2 above under the School Level. International schools have already been discussed in connection with the medium of instruction, which would determine the true type of school they are. There are also ethnic schools that struggle to maintain the language and culture of a minority group, such as the Korean heritage schools in Japan. Struggling with no government subsidies, they typically teach Korean and, later, English to students born and raised in Japan as native speakers of Japanese, who can thereby become to some extent trilingual.

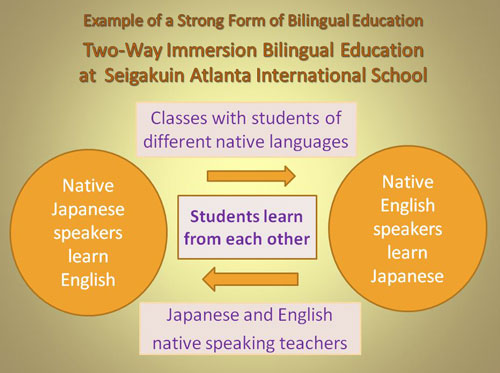

Finally there are bilingual schools, although student outcomes need to be confirmed, with some whole school systems in Europe and elsewhere applying the principles of bilingualism. One strong form of bilingual education is two-way or dual language education, illustrated below in Chart 3. Seigakuin Atlanta International School can also be called a bilingual school. They aim to balance the two languages, with the additional merit of leveraging both native languages so that all students can in effect act as teachers. The Vienna Bilingual Schools (Oka, 2003, pp. 49-64) are quite similar, with native speakers of German and English learning from each other.

Bilingualism at the Disciplinary Level

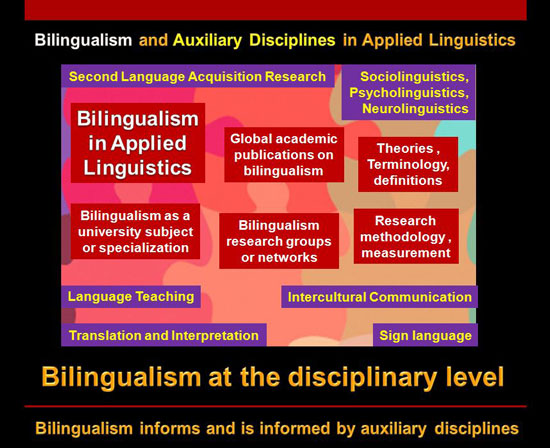

The two sections at the bottom of Chart 2 are combined in Chart 4 below:

To locate bilingualism as an academic field logically, going from the general to the specific, linguistics is divided into theoretical and applied disciplines. Applied linguistics includes many areas such as language teaching and bilingualism. Bilingualism can then be divided into different areas, with bilingual education as one subset of bilingualism, which can be further subdivided into types of bilingual education.

Proceeding from the general to the specific characterizes a vertical analysis, whereas a horizontal analysis would align different fields and mature disciplines, many of which can be mutually informative. The main difference between a field and a discipline in this context is that a field covers whole areas of study, whereas only parts of each field are selectively developed into disciplines, with academic societies, educational programs, methodologies, and a body of research literature. In interdisciplinary research, in order to provide a fuller picture of complex subjects such as human activities, academic disciplines often utilize the methods and research results of related or surrounding disciplines.

While the first four levels of bilingualism in Charts 1 and 2 apply to bilingualism as observed in daily life in the world, bilingualism at the disciplinary level involves the practices and principles of the academic discipline of bilingualism as well as related disciplines in applied linguistics. The related or bordering disciplines, only some of which are listed in Charts 2 and 4, can serve as auxiliary to bilingualism research, but from the standpoint of other disciplines in applied linguistics, the research findings and theories of bilingualism could also serve as auxiliary to their research. It is in this sense that Chart 4 above states that bilingualism informs and is informed by auxiliary disciplines.

Bilingualism at the disciplinary level includes academic activities such as a) research centers, university or graduate school programs with a major related to bilingualism, b) a body of literature in various publications with research findings from studies worldwide, c) academic societies, research groups or research-based networks, including online discussion groups, d) theories or concepts developed to account for languages in contact at various levels, terminology to describe bilingual phenomena, with some terms unique to this field, and definitions to maintain clarity and consistency, and e) research methods and the means to measure the phenomena of bilingualism, often drawn from different disciplines.

Many activities of bilingualism at the disciplinary level could involve auxiliary disciplines, interdisciplinary research, or collaboration with scholars in other countries and fields. Chart 4 names eight disciplines in applied linguistics that border on bilingualism as fields, written yellow on a purple background. Their methods or findings could inform bilingualism research, while their theories or practices could be informed by bilingualism.

"How Bilingualism Informs Language Teaching" (McCarty, 2013) demonstrated many ways that language teaching practices could draw from findings in the discipline of bilingualism, so one particularly fertile combination of disciplines in applied linguistics would be bilingualism and language teaching.

Translation and interpretation are interdependent with bilingualism, for one thing because translators and interpreters must be bilingual or multilingual. Thus translation and interpretation could be considered a part of the bilingualism field, but they also have distinct characteristics such as their own academic societies and a body of literature that distinguish them as a separate discipline. At expert levels, translation and interpretation can even diverge into separate specializations, such as simultaneous interpretation.

Bilingualism intersects with the discipline of intercultural communication in the communicative aspects of using two or more languages across cultures. Chart 2 above placed cultural aspects of bilingualism at the individual, family and societal levels. People of mixed cultural heritage or experience have a compound or distinct cultural identity along with more choices in life. In international families or for people living abroad, intercultural communication is a daily challenge. In multicultural societies these issues are magnified to the scale of different cultural groups sharing the same space. Intercultural training may be useful for sojourners who do not stay long enough in a foreign country to consider learning its language worth the effort. Instead, training is available in anticipating and adjusting to cultural differences, generally or regarding specific regions. Otherwise intercultural communication might be considered interdependent with bilingualism, since there are no shortcuts around language acquisition to deeply understand a culture.

Sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, and neurolinguistics are among the disciplines in applied linguistics that provide experimental methods and theoretical frameworks to analyze bilingual phenomena. Sociolinguistics, for example, supports family bilingualism research, charting the languages used between each member of an intercultural family. Psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics represent scientific measurements of the brain that will gradually contribute concrete evidence to theories of languages in contact at the individual level. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is increasingly used to track brain activity under different language stimuli. Brain science is a young field whose applications will gradually broaden.

Among other areas of applied linguistics in Chart 4, sign language is included as a discipline related to bilingualism. For one thing, a person who functions in sign language and another language to some extent is considered bilingual, as would someone who could function in two different systems of sign language or interpersonal communication. Sign language may serve as an example where connections could be drawn with bilingualism resulting in unexpected insights into language or communication.

Conclusion to the Series

Being a taxonomy, this series could only suggest the skeletal outlines of a vast field. Levels and components constituting bilingualism, with applications to language teaching in Japan and elsewhere, were proposed out of the author's experience and research. It is hoped that this article, along with the many previous ones, will contribute to a fuller understanding of the field of bilingualism.

-

References

- Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (4th ed.). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Bostwick, R.M. (2004). What is Immersion? Numazu, Shizuoka, Japan: Katoh Gakuen. Retrieved from http://bi-lingual.com/school/INFO/WhatIsImmersion.html

- McCarty, S. (2010b). Bilingual child-raising possibilities in Japan. Child Research Net: Research Papers. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2010_02_03.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/140.html

- McCarty, S. (2012a). Analyzing purposes of bilingual education." Tokyo: Child Research Net - Language Development and Education. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2012_01.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/171.html

- McCarty, S. (2012b). Analyzing types of bilingual education." Tokyo: Child Research Net - Language Development and Education. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2012_02.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/179.html

- McCarty, S. (2012c). Analyzing cases of bilingual education." Tokyo: Child Research Net - Language Development and Education. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2012_03.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/186.html

- McCarty, S. (2013). How bilingualism informs language teaching. Child Research Net: Language Development & Education. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2013_02.html

- Oka, H. (2003). Sekai no bairingarizumu [Bilingualism around the world]. In JACET Bairingarizumu Kenkyukai (Eds.), Nihon no bairingaru kyoiku: Gakko no jirei kara manabu [Bilingual education in Japan: Learning from actual school cases] (pp. 49-64). Tokyo: Sanshusha.