Taxonomy of Bilingualism

- 1. Levels of Bilingualism > the Individual Level (This paper)

- 2. Family and Societal Levels of Bilingualism

- 3. School and Academic Levels of Bilingualism

Introduction

This article begins the fourth series of papers on bilingualism that the author has written for Child Research Net. The first series had articles on bilingual child-raising, biculturalism, and concepts in the field of bilingualism. The second series was on bilingual education, its purposes, types, and cases that could be used in a university course related to bilingualism. The third series applied bilingualism to language teaching. Its first article clarified the various meanings of 'bilingualism' and showed why bilingualism should be considered a realistic goal of second or foreign language learning. The second article applied a developmental bilingual perspective to language teaching. Learning was conceived as a process of organic growth, with each person having a unique developmental path. With 'being or becoming bilingual' properly understood as a matter of degree rather than as an idealized state, the goal could be identified as bilingual functioning to a useful extent according to the needs of the individual (see also McCarty, 2008). Furthermore, applying first language acquisition research findings and the demonstrated capacity of infants to develop two native languages, many ways were presented that bilingualism can inform language teaching.

This fourth series presents a taxonomy of the various phenomena of bilingualism, with a view to how it fills out the context of language teaching. A taxonomy is a classification like an anatomy, except more summarized than detailed, and here the phenomena are sorted according to levels of bilingualism. Previous articles have been more thoroughly researched, while an overall taxonomy must of necessity be concise. Yet here still the series is divided into three articles.

Over about 20 years the author has developed both the levels used in this series, and the taxonomy, which began with a survey of language teachers as to the scope of bilingualism in Japan (McCarty, 1995). The examples are occasionally specific to Japan and often applicable to language teaching, but bilingual phenomena in Japan can also be found elsewhere. If not for the bewildering linguistic diversity in some regions of the world such as southern Africa, this series could serve as a general taxonomy of bilingualism.

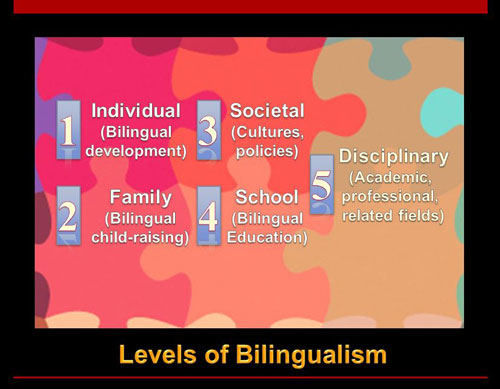

This taxonomy starts by classifying bilingual phenomena into five levels, the first four levels found occurring naturally in daily life, with the fifth level being the academic study of the first four levels (see Chart 1 below). This first article has introduced the series and aims to summarize the individual level of bilingualism. The second article will go on to the family and societal levels, then the third article will conclude the taxonomy by summarizing the school level (bilingual education) and the academic or disciplinary level (bilingualism as an area of study in applied linguistics).

Levels of Bilingualism

In teaching bilingualism courses, it has been helpful to contextualize complex bilingual phenomena by checking students' understanding of what kind or level of bilingualism is being discussed. The author therefore often draws a square grid with four boxes on the board and asks students, which level of bilingualism is this about, the individual, family, societal, or school level? It is explained that bilingualism includes 1) the individual level, such as one's own bilingual and bicultural development; 2) the family level, such as bilingual child-raising; 3) the societal level, such as cultural issues or government policies toward minorities; and 4) the school level, particularly bilingual education.

Rather than just an abstract understanding of concepts, these four levels help learners understand bilingual phenomena in their fuller dimensionality, in the context where they actually manifest. For example, it is important to distinguish between bilingual child-raising at home and bilingual education in schools, which these levels help explain. As another example, in discussing the overly idealized image of the bilingual in Japan, which sounds boastful to attribute to oneself, students can be referred to the square grid to focus on the individual level of bilingual development and how it is a matter of degree. Family bilingualism often involves analyzing what languages are spoken among members of an international family. Societal bilingualism takes up broader issues such as the percentage of speakers of different languages in a geographical area. Sometimes human rights are not protected, such as the right to choose the languages through which one's children are educated. At the individual level, people should have the right to their own linguistic and cultural identity, as more languages bring more choices and therefore greater freedom.

There is some overlap and mutual influence among the four levels, which is illustrated by the puzzle background rather than straight lines in Chart 1 above. It was introduced in the previous series to show how, in language teaching, compared to a focus on teaching discrete aspects of a target language, a bilingual perspective provides a broader view of the dimensions involved in language development.

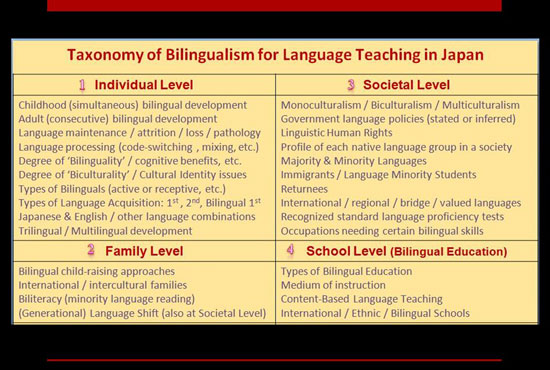

Taxonomy of Bilingualism

Common phenomena and issues connected to bilingualism are illustrated in Chart 2 below. In some ways the items reflect the viewpoint of English language teaching in Japan, thus falling short of the full complexity of bilingual phenomena. This taxonomy nevertheless aims for a wide understanding of the field of bilingualism, adding some anatomical details to the skeletal levels. This brief series aims to provide an overview of bilingual phenomena, with example situations often reflecting languages in contact in Japan. For more encyclopedic coverage, see books such as Baker (2006), or further details particularly in McCarty (2010a, 2010b), since this series tries to avoid repeating the contents of previous articles. Chart 2 covers just the naturally occurring levels where different languages come into contact in daily life, and will suffice for the individual level of bilingualism discussed in this article.

Bilingualism at the Individual Level

Bilingual development is the chief issue at the individual level, and there are important differences according to when two languages (or more) are started. Starting at birth or infancy is called simultaneous bilingualism, whereas starting another language after a native language mindset is established is called consecutive or sequential bilingualism. Corresponding types of language acquisition were proposed previously (McCarty, 2013). Infants evidently have the capacity for natural language acquisition, whereas a deliberate effort or study is needed when languages are started after puberty. There seem to be other stages or critical periods around age three, six, and pre-adolescence where languages are acquired more easily than after puberty, and very generally speaking, the older one starts languages, the more difficult it is to acquire them. Theories of critical periods at the individual level explain much about the failures of foreign language education in many countries where one language is dominant: too little exposure, not often enough, started too late, and with too few opportunities to use the non-dominant language actively and authentically.

Bilingual development is affected by various factors such as the frequency and amount of input, opportunities for interaction, the perceived need for certain languages, or the willingness of the individual to communicate with diverse others. Moreover, continuing with the above chart, language acquired needs to be maintained by use, or else attrition begins, such as less fluency in speaking. Language loss means that a language previously acquired to some extent, usually in early childhood, becomes irretrievable. Studies have shown that languages are more easily acquired and quickly forgotten for small children, and more difficult to learn but also more difficult to forget as they grow older. Some school-age Japanese returnees who lived abroad for several years seemed to have lost their native language, but when they returned to Japan their Japanese fluency revived, which showed that their L1 was not lost but rather dormant from not being used. Another crucial issue for returnees is usually maintenance of the L2 they acquired abroad (Childs, 2004). Language pathology or various developmental problems need to be treated, but it is important to understand that bilingualism itself does not cause such problems. Even using one language instead of two, any language disability would similarly affect that one language. Social problems are also often misinterpreted as drawbacks of bilingualism, whereas the problem is not being or becoming bilingual but rather how others respond to the bilingual being different from the majority.

Language processing is another area studied in bilinguals, and the general conclusion is that they mix languages strategically and creatively with a view to the linguistic repertoire of listeners. To insert words from another language into the syntactical structure of one language can be called code-mixing, whereas alternating languages and their syntactical structures can be termed code-switching. Bilinguals often enrich communication with each other by mixing languages, not for lack of vocabulary but because they choose cultural nuances of one or the other language that better suit what they aim to express.

Degree of bilinguality in the chart refers to how bilingual an individual is. There is no clear line between being monolingual and bilingual, and each person has a different mix of the four skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Ultimately, however, individuals only need to be bilingual in the ways and to the extent sufficient for their own purposes. Cognitive benefits of bilinguality refer to the mental and ethical benefits that tend to accrue to people who grow up or become bilingual. A large-scale survey including native speakers of Japanese and of English showed that both usually gained such cognitive benefits of a wider linguistic repertoire and a broader perspective than when they were monolingual (McCarty, 1999). Degree of biculturality similarly refers to how bicultural an individual is (another cause of cognitive benefits shown in McCarty, 1999). Although precise measurements of biculturality seem hardly possible, one might qualitatively research the extent to which an individual can see each situation through the eyes of two cultural viewpoints and thus have the choice of different approaches to the same issue.

There are a number of types of bilinguals posited in the literature, including the distinction between simultaneous and consecutive bilingualism mentioned above. Another important distinction is between active bilinguals who display proficiency in speaking and perhaps writing in both languages, versus receptive bilinguals who speak mainly one language. They are sometimes called receiving bilinguals because they understand most of what they hear in their weaker language. It is unwise to call them passive because they are actively listening, like some children of international marriages raised in Japan who respond to English or another language in Japanese, with the conversation proceeding at a normal pace in two languages. When such children study abroad, it is not unusual for them to become fluent within several weeks, activating the language they had quietly and invisibly built up for years. The process of turning orally comprehended language (listening skill) into active production (speaking skill), when it becomes necessary to speak in another language regularly, also applies to foreign language learning. Acquired language (through listening or reading) is always more than what the individual expresses or can use actively (in speaking or writing). It is a common mistake to measure language acquisition by speaking.

Language acquisition is another dimension of the individual level, and four types of language acquisition were previously proposed (McCarty, 2013). Two of the four, first language acquisition and bilingual acquisition (from infancy), share a common characteristic due to the innate ability of babies to acquire more than one native language, often because their parents or guardians speak different languages regularly to them from birth. Trilingual or multilingual development is the last item listed for the individual level, and there can be qualitative differences in acquiring more than two languages. Having learned a second language, for example, similar skills are employed to make the learning of further languages more efficient and rapid. While second or foreign language acquisition clearly corresponds to consecutive bilingualism, multilingual acquisition is usually of a consecutive nature because children tend to have up to two regular guardians. For similar reasons, bilingualism is an apt term in most instances with two parents or guardians, and bilingualism can serve as the umbrella term including multilingualism in its meaning.

There are other types of bilingualism that are of concern to specialists. The question of which language combinations are involved applies to all levels, and the mention of Japanese and English only in Chart 1 suggests a context of teaching English in Japan that does not confine most of the taxonomy.

-

References

- Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (4th ed.). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Childs, M. (2004, July 20). Kids learn and forget quickly. Daily Yomiuri.

- McCarty, S. (1995). Defining the scope of the Bilingualism N-SIG [a national special interest group of the Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT)]. Japan Journal of Multilingualism and Multiculturalism, 1 (1), 36-43.

- McCarty, S. (1999). Nigengo nibunka heiyo no igi: Seijin bairingaru no jiko kansatsu [What it means to combine two languages and cultures: Self-observations of bilingual adults]. In M. Yamamoto (Ed.), Bairingaru no Sekai [World of the Bilingual] (pp. 133-159). Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

- McCarty, S. (2008). The bilingual perspective versus the street lamp syndrome. IATEFL Voices, Issue 203, pp. 3-4. Canterbury, UK: International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language.

- McCarty, S. (2010a). Bilingualism concepts and viewpoints. Child Research Net: Research Papers. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2010_02_02.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/137.html

- McCarty, S. (2010b). Bilingual child-raising possibilities in Japan. Child Research Net: Research Papers. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2010_02_03.html - or in Japanese at http://www.blog.crn.or.jp/report/02/140.html

- McCarty, S. (2013). How bilingualism informs language teaching. Child Research Net: Language Development & Education. Retrieved from http://www.childresearch.net/papers/language/2013_02.html