When placed in an extremely difficult situation, Japanese feel that they have to exert tenacious effort (ganbari), pledge to do ganbari, exchange encouraging expressions such as 'ganbarō!' (Let's persevere together)!', and send encouragement like 'ganbare (Hang on! Work Hard)!,' regardless of age or gender (p. 3, Amanuma 1987).

The Japanese term ganbari means exerting tenacious effort and hard work, persevering, and not giving up. The concept and practice of ganbari are prevalent in everyday lives in Japan. Scholars argue that it is often a key cultural value that guides students' motivation and attitudes in Japan (see Amanuma, 1987). From an early age, Japanese children are expected to cultivate the spirit and habit of ganbari, trying hard and exerting effort, often by persevering and hanging on even in the face of failure (see Yamamoto & Satoh, in press, for details). Japanese parents and other adults explicitly or implicitly try to cultivate ganbari by encouraging young children to be persistent and apply greater efforts. For example, when young children are working on tasks, parents or teachers often encourage them to complete the task and not giving up by saying "Bring ganbari! (Don't give up! Or Try harder!)" Japanese teachers tend not to intervene quickly when children are frustrated and wait until children actually do try harder. Teachers also sometimes assign young students activities and tasks that are slightly beyond their capabilities and encourage them not to give up. Adults tend to view students' struggling or failing as an opportunity to cultivate ganbari (Yamamoto & Satoh, in press). Many schools employ activities that focus on fostering the ganbari spirit such as a marathon race. Through these socialization processes, children are expected to be willing to exert effort when learning or engaged in tasks.

Scholars who observed Japanese preschools noted that teachers tend to focus on children's attitudes rather than outcomes in their activities and work. Japanese teachers usually focus on praising children who tried hard and completed tasks rather than children who were competent. They may also criticize children if their work did not reflect their best effort (Lewis, 1985; Shigaki, 1983). In general, Japanese teachers and parents believe that continuous efforts and hard work, more than abilities, determine academic outcomes. Being able to persevere and exert efforts are considered to be important characteristics that need to be developed. According to a cross-cultural study, in first grade, Japanese children demonstrate greater task persistence than American children (Heine et al., 2001). Japanese teachers list perseverance and concentration in addition to good socio-emotional skills to function as a group member as critical pre-academic skills (Lewis, 1995; Yamamoto & Satoh, in press).

Is the concept of ganbari unique to Japanese culture and not found in Western culture? Based on cultural comparisons, some scholars argue that East Asian cultures tend to value and emphasize effort more than Western cultures. For instance, people in East Asia tend to believe that effort determines children's academic failure or success whereas Western people believe that innate abilities do so (Holloway, 1987; Li, 2012). In the United States, teachers and parents tend to believe that children's innate ability is a more powerful determinant of their outcomes and performance than effort. In the U.S., because adults focus on fostering self-esteem in children, they also tend to highlight each child's strengths more than weaknesses that can be improved by exerting more effort (Dweck, 2017; Li, 2012). According to an experimental study, East Asian mothers tend to focus on areas where children can do better while American mothers tend to focus on their children's strengths.

Nevertheless, increasing attention has been paid to the value of efforts and perseverance in children's development and educational processes in the U.S. For example, a psychological concept called GRIT, which shares some commonalities with ganbari, has received considerable attention in the field of education. GRIT is defined as "perseverance and passion for long-term goals" and "working strenuously toward challenges, maintaining effort and interest over years despite failure, adversity, and plateaus in progress" (Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007). GRIT is not found to be associated with IQ like ganbari. Scholars are not yet sure how individuals can be gritty. However, Duckworth implies that having a growth mindset may be critical. According to Dweck (2017), children with a growth mindset believe that their intelligence can improve by exerting more effort. These children tend to exert greater efforts even when faced with challenges or failure as they believe that they can become smarter. On the other hand, children with a fixed mindset believe that natural intelligence will itself determine their outcomes, and thus intelligent people do not need to exert efforts. Over the last ten years, schools and teachers in the U.S. have tried to cultivate growth mindset and GRIT in their students. However, as Dweck (2017) reported, such processes have been challenging. While ganbari has been passed down across generations as a cultural virtue in Japan, GRIT or a growth mindset is a relatively new psychological concept introduced to teachers and schools in the U.S.

What is not known yet is children's developing views related to the concept of ganbari. It is well known that Japanese teachers and parents try to cultivate ganbari in children from a young age. How do Japanese children conceptualize ganbari in their learning processes from a young age, such as first grade? Are there concepts like ganbari that often require children's persistence and efforts in the U.S.? Do children in Japan internalize the value of ganbari more than children in the U.S.? The goal of this study is to examine first graders' concepts related to ganbari in Japan and the U.S.

Method

In 2013 and 2014, several research assistants and I conducted interviews with 180 first graders (109 in Japan and 71 in the U.S.) who attended public schools in Osaka in Japan and two states in New England in the U.S. The children who participated in this study were 6- or 7-year-olds. To elicit young children's narratives, we used a story-completion method that is widely used for interviews with young children. As young children still cannot process abstract concepts or articulate their thoughts clearly, this method is considered to be a valid way to elicit children's thoughts, feelings, and ideas. While showing black and white pictures, an interviewer read various types of standardized short stories beginning with children's learning processes. The gender of the children in the pictures and the stories were matched with the gender of the participants. For this paper, I analyzed two stories that illustrated children's learning attitudes and their outcomes. One story is about a child who tries hard and is finally able to read a book. The other story is about a child who tries to count apples at a store but gives up before completion. An interviewer then asked the child to continue each tale. Whenever children mentioned stories or concepts related to learning, an interviewer probed by asking if that is good or not good and why it is good or not good or what is good/not good about that. The interviewer kept probing until the child repeated the same concepts or showed some sign that he or she was finished. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. At the end of each story, the interviewer asked if the child liked the protagonist child in the story and enquired after the reasons for liking or disliking the protagonist.

First Graders' Views

Values and meanings of ganbari: Japanese children's viewsLet's look at narratives of the following Japanese girl (Maho as a pseudonym). After the beginning of a story about a child who gave up counting apples at a store, Maho continued the story as follows.

Child: Her mom said "Try it (ganbatte) one more time," then she started to count one more time. Then her mom and dad praised her and said, "Good for you!"

Interviewer: Is it good or not good?

Child: Good.

Interviewer: Why is it good?

Child: Because if one tries hard (ganbattara), puts in some effort, counts, that person would like numbers.

Interviewer: What's good about trying hard, putting in effort, counting, and liking numbers?

Child: She will understand addition, subtraction, and multiplication. And when someone says "what is it?" she can say "yes!" and understands it. And when she becomes a second grader or a six grader, she will like to work on addition.

This example demonstrates the child's sophisticated understanding related to ganbari. Here Maho shows her beliefs that ganbari would lead to positive feelings such as liking to count as well as positive outcomes such as being able to solve advanced math problems. She also mentioned a parent who encouraged the child by saying "ganbatte!" To the question asking if she liked this protagonist, Maho noted that she did not like the child in the story because the protagonist child gave up easily, indicating her disapproval of the child's attitude to learning. She noted that "If you try hard, it will be good for you." These statements reveal Maho's understanding that ganbari (trying hard and not giving up) is important.

About 54 percent of the Japanese children in this study voluntarily mentioned the term "ganbaru" or "ganbari" in their stories. Their narratives indicated children's values regarding ganbari and recognition of the benefits of ganbari in their learning processes. For example, significant numbers of children mentioned that ganbari is necessary to lead to achievement or to acquire skills. Moreover, success or better outcomes gained after ganbari are felt to lead on to positive feelings, such as joy and a sense of achievement. One child said, "She couldn't count them after trying a few times, but she could do so after trying a bit harder (ganbatta) and felt happy". Another child mentioned, "If he tries, he will think that he did it. When he thinks he did it, he will be able to count higher numbers than those apples." These narratives demonstrate their beliefs in which persistent efforts can lead to success and motivation. Some children also mentioned the importance of internal feelings and motivation. One child noted, "If you are motivated and have a spirit of trying harder (ganbaru kimochi), you can memorize them." Many children also expressed values related to ganbari: "It's good to ganbaru, but it's not good not to ganbaru." Overall, these narratives demonstrate Japanese children's beliefs such as values in ganbari, benefits gained from ganbari, and feelings associated with ganbari.

Practicing, trying hard, and not giving up: American children's narrativesIs ganbari a uniquely Japanese concept? There is no single noun that is equivalent to ganbari in English. However, analyses of children's narratives show that many American children in this study also believe that it is essential to exert efforts and to not give up when engaging in tasks or learning. After hearing a story of a child who tried hard and could finally read a book, one child (Emily as a pseudonym) continued the story as follows.

Child: Her mom helps her and reads. And she reads to her and practices and practices and practices every single time so she can learn how to read a lot of times so then she can read by herself.

Interviewer: What's good about practicing and practicing and being able to read by herself?

Child: Because if you just quit and don't want to do anyth--you don't want to do it, you get to a grade, and you are gonna be like, "How can I do this because I don't know?"

Practicing and practicing every single time seems similar to the concept of ganbari. Emily also believes that one has to practice repeatedly by not giving up to acquire skills and better outcomes such as reading a book. American children mentioned terms such as "trying hard," "keep trying," and "not giving up" in their narratives. Many American children also mentioned that trying hard and not giving up is important. Like Japanese children, they mentioned that continuous effort would lead to improvement, better outcomes, and achievement such as getting skills or a good grade. Values placed on constant effort are similar to attitudes toward ganbari. Thus, regardless of cultures, young children seem to be aware of the values of exerting efforts and not giving up in their learning processes.

So do American children and Japanese children share similar views related to ganbari? American children tended to focus on outcomes and performance more than Japanese children when they mentioned the importance of exerting efforts. Japanese children mentioned ganbari in relation to spirits and processes more than American children. Japanese children may think that it is important to try harder even if one cannot succeed or even if it may not necessarily lead to better outcomes. But for American children, practicing or trying hard may be viewed as a strategy to achieve. American children tended to mention effort and practices in the context of personal choice and strategy. Japanese children tended to mention ganbari in the context of obligation by using the phrase such as "must" or "have to." While American children are aware of the importance of continuous efforts, they may not feel that putting in effort is a moral virtue or obligation like Japanese children.

Is doing ganbari good? Cross-cultural differencesAnalyses of children's narratives demonstrate that children are aware of the importance of exerting efforts in learning processes from a young age, regardless of cultures. Are there different patterns across the two countries then? In other words, do Japanese children tend to value effort more than children in the U.S.? At the end of each story, interviewers asked children if they liked the child in each story and enquired after reasons for liking or disliking the child. By analyzing their responses, we can see children's values placed on ganbari.

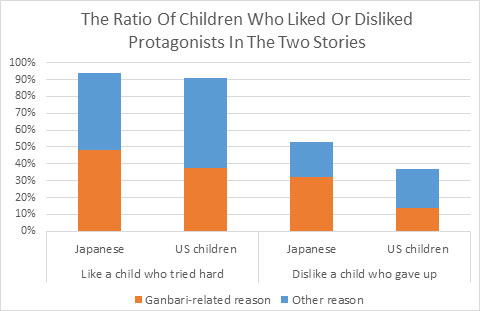

Most children in Japan and the United States liked the child who worked hard and could finally read a book (see Figure 1). About 94% of the Japanese children and 91% of the American children liked the positive protagonist in the story. However, when children mentioned a reason for liking the child in the story, 51% of the Japanese children and 41% of the American children specifically mentioned a ganbari/effort-related reason (e.g., because she did ganbari) . Other reasons given for liking the child in the story included appearance (e.g. because she is cute) and a successful outcome (e.g., because she could read a book) for both Japanese and American children.

There were more cultural differences in the story of a child who gave up counting apples at a store and did not exert efforts (see Figure 1). About 53% of the Japanese children and 37% of the American children said they did not like the child in the story. More Japanese children noted the child's attitudes of not exerting efforts as a reason for disliking the child than American children. Among those who did not like the child in the story, 61% of Japanese children mentioned ganbari or learning attitudes-related reasons (e.g., because he gave up; because she did not try hard) as a reason for disliking the child in the story while 38% of the American children did so. Other children mentioned reasons related to outcomes (e.g., because he couldn't count), relationships with adults (e.g., because he didn't listen to his parents), personal characteristics (e.g., because he is not nice), or physical appearance (e.g., because she is not cute; because he doesn't have nice hair).

|

These numbers indicate that children in both countries generally agree with the learning attitudes of exerting efforts. However, when it comes to attitudes of not exerting efforts, more Japanese children expressed disapproval of such attitudes than American children. It may reflect strong values placed on perseverance and effort (ganbari) in Japanese culture. Analyses of reasons provided by children also demonstrate that Japanese children tend to focus more on attitudes in their learning processes compared to American children, who tend to focus more on outcomes.

Discussion

From an early age, most children have internalized cultural values that are prevalent in their environments. At age 6 or 7, Japanese children seem to have developed the belief that exerting efforts is critical to their learning processes to a greater extent than American children have.

It is important to note that this research was conducted in Osaka and two states in the U.S. and may not be an overall representation of children in the two countries. Moreover, not all of the children in this study valued ganbari in Japan. A few children mentioned that children do not always need to do ganbari. In interviews with Japanese mothers, a few mothers noted that excessive ganbari may not be healthy and could be a source of stress for their children. Some noted that children could do ganbari naturally if they are engaged in activities/areas they feel passionate about, and thus ganbari should not be forced on them. However, as more than half of the Japanese children in this study voluntarily mentioned the term ganbari in these stories, ganbari may be considered to be a critical process by Japanese children.

In this study, I did not examine how children's views of ganbari are related to their actual behavior patterns. My follow-up interviews indicate that values on ganbari do not always lead to their ganbari behavior. Even when children recognize that doing ganbari is essential to learning processes, not all children can exert efforts. In future studies, it is essential to understand why some children are able to try hard and not give up while others are less able, especially when they are confronted with obstacles and challenges. Research studies on ganbari or GRIT are still scarce despite its significance on children's learning and developmental processes. I hope there will be further systematic studies on these concepts in the future.

References

- Amanuma, K. (1987). Ganbari no kōzō: Nihonjin no kōdō genri [The structure of ganbari: Principles of Japanese behaviors]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan.

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087-1101.

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). The journal to children's mindsets―and beyond. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 139-144.

- Heine, S. J., Kitayama, S., Lehman, D. R., Takata, T., Ide, E., Leung, C., & Matsumoto, H. (2001). Divergent consequences of success and failure in Japan and North America: An investigation of self-improving motivations and malleable selves. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 599-615.

- Holloway, S. (1988). Concepts of ability and effort in Japan and the United States. Review of Educational Research, 58(3), 327-345.

- Lewis, C. C. (1995). Educating hearts and minds: Reflections on Japanese preschool and elementary education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Li, J. (2012). Cultural foundations of learning: East and West. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Shigaki, I. (1983). Child care practices in Japan and the United States: How do they reflect cultural values in young children? Young Children, 38(4), 13-24.

- Yamamoto, Y., & Satoh, E. (in press). Ganbari: Cultivating perseverance and motivation in early childhood education in Japan. In O. Saracho (Ed.), Contemporary research on motivation in early childhood education. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Acknowledgment

A part of this research was supported by a grant from the Mayekawa Foundation.

Yoko Yamamoto

Yoko Yamamoto