In the previous article, Inclusive Education in Finland (1), I reported on the underlying ideas and rough history of inclusive education in Finland and who is the targets of inclusive education. As stated, the way of understanding and promoting inclusive education is greatly influenced by a country's religious values, history, culture, and economic background. Therefore, it is necessary to look at it from many different angles in order to understand inclusive education in that country. In the case of Finland, educational reforms in the 1970s led to the introduction of special needs education teachers without overseeing a classroom in each regular school. In 2010, a three-tiered support system was introduced. In this report, I will describe how the three-tiered support system works.

The process for the introduction of the three levels of support

Before the introduction of the three-tiered support, a major change occurred in the framework of special needs education with the revision of the Basic Education Act in 1997. Children with severe disabilities, who had previously been placed under the jurisdiction of the welfare domain and could only receive segregated education, were now able to receive education at regular schools. Consequently, the number of children with special needs in the educational domain has increased rapidly during the 2000s. In response to this trend, education officials from 10 large municipalities assembled to express their opinions on the confusion and concerns in the educational field caused by this increase, as well as what was acceptable in schools, and they compiled a report in 2006. In response, the Ministry of Education and Culture established a steering committee to develop strategies for the long-term development of special support. In 2007, an initial draft of the revised Basic Education Act related to special support was issued. Simultaneously, between 2007 and 2010, various municipal projects supported by the Ministry of Education and Culture developed their own strategies for special needs education, conducted early intervention and teacher training on special support. The results were reported to the Ministry of Education and Culture. Based on the results of these practical reports from the municipalities, the Diet approved the final draft of the Revised Basic Education Act in 2010. The centerpiece of this revision was the introduction of three-tiered support, modeled after the Response-to-Intervention (RTI), which was already practiced in the United States.

When discussing this trend with a Finnish researcher, she said, "In Finland, this kind of voice from local government education officials moved the Ministry of Education and Culture and even led to the revision of the law and the introduction of a new education system." I remember her words, expressed with deep conviction, "I am proud that we were able to change the education system in such a bottom-up way." I believe that it is precisely because Finland is a small country with a population of 5.54 million that we can listen to the voices of the people on the ground and quickly implement educational reforms.

Details of the three levels of support

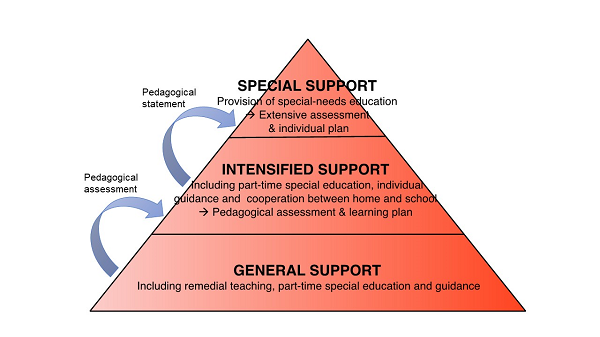

The main goal of the three-tiered support is to provide early identification and intervention; thus, support can be provided to all children struggling with learning and school life. The first level of support is called "general support" and includes all children. This begins when the need for support is perceived. It includes remedial teaching, in-class support by a special needs teacher, or taking individual or small group instruction outside the classroom (commonly known as "part-time special education"). This support is considered temporary and does not require any special documentation or statistical reporting of the support received by the child.

The second level of support is called "intensified support" and is provided when temporary support is deemed insufficient. First, an educational assessment is conducted by the child's homeroom teacher, special needs teacher, and parents/guardians, and a subject-specific learning plan is developed (e.g., Math, Reading). This learning plan is designed for a short period, from a few weeks to a few months. Upon completion, an assessment is conducted to discuss whether to continue the intensified support or stop providing support, or if further support is needed.

The third level is referred to as "special support" and is provided when intensified support is deemed insufficient. This phase requires the development of a pedagogical statement based on extensive assessment and approval from the leadership team, including the school principal. At this stage, a more detailed Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is developed, and support is provided accordingly. To enroll in a special needs class, students must be approved to receive this special support.

According to 2018 statistics, the number of children receiving intensified support was 10.6%, and the number of children receiving special support was 8.1%. In addition, part-time special education, as mentioned in Inclusive Education in Finland (1), is available at all stages, and the number of children receiving this part-time special education is 22% of the total. Furthermore, 35.5% of the children receiving special support were totally segregated (i.e., received classes only in special needs classes or special needs schools), while the rest were enrolled in regular classes in one form or another, regardless of the amount of time they spent there.

Challenges of the three-tiered support

Although this model appears to be highly effective in achieving the goal of early identification and intervention, various challenges have also been identified. For example, the introduction of the three-tiered support has increased the workload of teachers and by intervening in mild cases, there is a risk that children who truly need special support may be overlooked. In addition, as for the newly introduced second stage, the law does not clearly stipulate when a child should receive intensified support, and each school is left to its own practice. Extending beyond the second stage, clear guidelines on what kind of support should be provided at each stage are not stipulated and practices seem to vary among regions and among schools.

This may be related to the characteristics of the Finnish school system. In Finland, the autonomy of schools and teachers is highly valued, and educational practices vary between regions and schools. While this may be advantageous in that teachers and schools are trusted, one challenge is the lack of clear guidelines; even if there are good practices (or failures) at each school, they cannot be accumulated and shared among other schools. There is a need for organizations to consolidate practices in each region and school, share them among schools, and make teaching materials and other resources available.

Three-tiered support from the eyes of a parent

Thus far, my child does not receive any intensified or special support services; therefore, I have not experienced the process by which they are provided. However, at the parent-teacher conferences held at the beginning of each semester, there is always an introduction to the special needs teacher in charge of my daughter's class, an explanation of how she will be involved, and an announcement that we can contact her if we would like to discuss anything. Furthermore, as my daughter has told me, some of her friends receive individualized instruction (i.e., part-time special education) from that teacher several times a week. Nevertheless, my daughter and her classmates do not seem to feel anything special about this. In Japan, many parents feel that their children are labeled as "disabled" by others when they receive special support; here, the atmosphere suggests that it is better to receive necessary support and the child is not special just because he/she receives it. I think that one of the reasons in making it easier for both children and parents to receive support is that a diagnosis from a medical institution is not required.

References

- Björn, P. M., Aro, M. T., Koponen, T. K., Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. H. (2016). The many faces of special education within RTI frameworks in the United States and Finland. Learning Disability Quarterly, 39(1), 58-66.

- Eklund, G., Sundqvist, C., Lindell, M., & Toppinen, H. (2021). A study of Finnish primary school teachers' experiences of their role and competences by implementing the three-tiered support. Special Needs Education, 36(5), 729-742.

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2016). National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish National Board of Education.

- Pesonen, H., Itkonen, T., Jahnukainen, M., Kontu, E., Kokko, T., Ojala, T., & Pirttimaa, R. (2015). The implementation of new special education legislation in Finland. Educational Policy, 29(1), 162-178.

- Yada, A. (2020). Different processes towards inclusion: A cross-cultural investigation of teachers' self-efficacy in Japan and Finland.

Available at: https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/67827/978-951-39-8073-3_vaitos_2020_02_28.pdf?sequence=1

Ph.D. (Education), University of Jyväskylä, Finland; Licensed Psychologist and former Clinical Psychologist, Japan. She is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the Centre of Excellence for Learning Dynamics and Intervention Research (InterLearn), University of Jyväskylä and University of Turku, and a visiting researcher at the Center for Sustainable Development Studies, Toyo University.

After completing the master’s degree program at Aoyama Gakuin University, she worked as a clinical psychologist for six years at a child developmental center, a child psychiatry clinic, and an elementary school. She mainly provided counseling and consultation to children with special needs and their parents and teachers.

Interested in inclusive education, where children with and without special needs learn together in the same place, she moved to Finland with her husband in 2013. She continues her research on inclusive education. Based on her experience of childbirth and childcare in Finland, she is also interested in Finnish neuvola, early childhood education, and social welfare systems. She has conducted extensive research on these topics.