Introduction

Three law revisions enacted in 2018 clarified qualities and capabilities that should be nurtured in early childhood education in Japan, expressing them as three pillars--"foundation of knowledge and skills," "foundation of the ability to think, to make decisions and to express themselves and other abilities" and "attitudes of learning to learn and human qualities, among others." The revisions also specified "developments that should be achieved by the end of early childhood," urging efforts to collaborate with elementary school teachers through such means as sharing these developments, thereby promoting smooth transition to elementary school. While the importance of education through the environment remains intact, in order to establish a consistent learning environment between early childhood education and school education, which have two different cultures, the perspective of "nurturing emotional skills" becomes valuable.

Also, the "Course of Study for Kindergartens" enacted in 2018 specifies perspectives for enriching kindergarten education, including qualities and capabilities that should be nurtured, and improvements in teaching aligned with "proactive, interactive and deep learning" in school education adjusted to younger children. It also states that "when using information devices such as audiovisual teaching materials or computers, they should be considered in relation with children's experiences, for example, by providing complementary experiences that are difficult to come by in normal kindergarten life." In other words, it encourages the use of ICT as necessary in relation with children's experiences, thereby enriching such experiences.

Against this backdrop, I introduce how Finnish education policies are working effectively within a system where children's emotional skills are nurtured by society as a whole, and discuss the implications. I also reveal the positioning of media education in terms of ICT usage under the Finnish National Core Curriculum, which was revised ahead of Japan, and examine how media education functions organically in nurturing children's emotional skills as an entire society.

1. Education System in Finland

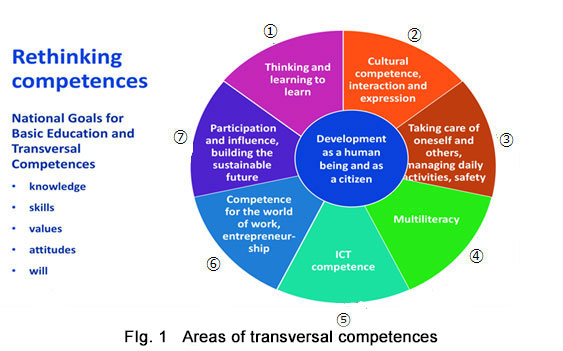

Basic education in Finland (ages 7-16; applies to elementary and lower secondary schools in Japan), sets seven areas of transversal competences: (1) thinking and learning to learn; (2) cultural competence, interaction and expression; (3) taking care of oneself and others, managing daily life activities, safety; (4) multiliteracy; (5) ICT competence; (6) competence for the world of work, entrepreneurship; and (7) participation and influence, building the sustainable future (see Figure 1). Meanwhile, six areas are defined for pre-primary education (age 6) by combining (4) and (5), and five areas for ECEC (ages 0-6) by further omitting (6).

2. Comparing Japan and Finland

I compared the perception of qualities and capabilities, the national curriculum and standards, and media education between Japan and Finland (see Table 1). In Japan, qualities and capabilities are captured through three pillars, and attempts are made to seamlessly connect them from early childhood to elementary school through "10 developments that should be achieved by the end of early childhood" (i.e., a healthy mind and body; independence; cooperativity; budding of morality and social norms; involvement with social life; budding of thinking skills; involvement with nature and respect for life; interest in and sense of numbers, diagrams and letters, among others; communication using words; and rich sensibility and expression).

| Qualities and Capabilities | Standards/Curriculum | Media Education | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Before Entering School | Foundations of the three pillars and 10 ideal developments | -"Course of Study for Kindergartens" -"Guidelines for Nursery Care at Day Nursery" -"Courses of Study and Childcare for Certified Centers for Early Childhood Education and Care" (i.e., facilities integrating kindergarten and day-care functions) | -Separated approach -Information education at school |

| After Entering School | Three pillars: "Attitudes of learning to learn and human qualities, among others" "Knowledge and skills" "Abilities to think, to make decisions, to express themselves and other abilities" | "Courses of Study" | ||

| Finland | Before Entering School | -Six qualities and capabilities

(Pre-primary: preparation for entering school) -Five qualities and capabilities (ECEC) |

-National Core Curriculum for Pre-Primary Education (2014) -National Core Curriculum for ECEC (2016) | -Integrated approach -Schools, families and the community think together |

| After Entering School | -Seven qualities and capabilities | -National Core Curriculum for basic education |

With regards to methods for nurturing such qualities and capabilities, in Japan, preschool education curricula are designed by referring to respective courses of studies or guidelines for kindergartens, day-care facilities, or centers for early childhood education and care. This implies that curricula are designed in a top-down manner under the supervision of the respective government agencies. Classroom plans--ranging from annual curricula according to facility type, to daily plans created primarily by home room teachers--and each child's individual plan tend to be handled separately, partially in consideration of the collective teaching approach from elementary school and onward.

As for media education, it tends to be perceived as information education implemented within schools as a cross-curricular matter, implying that it takes a "separated approach," independent from the local community or families.

Meanwhile, in Finland, qualities and capabilities are perceived as seamless in fostering "development as a human being and as a citizen." Also, the number of areas for qualities and capabilities to be developed shift from five to six, and then seven according to children's developmental stage. Curriculum is jointly developed by childcare practitioners (senior personnel) and university researchers, and each local curriculum is accompanied by a proprietary assessment plan. At facilities, such local curricula and plans are used more commonly than the "National Core Curriculum," meaning that each facility holds high discretion. Local curricula are developed by each region and "pedagogical activities" are planned in tandem with "individual plans." In other words, group plans are developed based on individual children's growths. This is made possible owing to the fact that childcare takes a small-group approach: children ages three and under act in groups of four, and children ages four and above act in groups of seven. It should be noted that teaching in elementary school and onward also mainly takes a small-group approach.

As for the positioning of media education, KAVI (The National Audiovisual Institute) undertakes national/regional initiatives, such as creating guidelines (including safety of media environment for children), developing teaching materials or providing professional development, and organizing events. In Finland, media education is interpreted as media literacy, which is an element of multiliteracy, which in turn is one of the qualities and capabilities. It takes an "integrated approach," engaging everyone from families, the country, local communities to schools, and is grounded deeply in daily life. For example, during media week which is carried out on a national scale, people consider how to deal with the Internet, events are carried out nationwide offering access to the latest information technologies, and it is common for entire families to attend such events. Importantly, the contents, plans and other aspects of such events are considered by KAVI, which is a governmental organization. The fact that media education is implemented as a society-wide initiative in an integrated manner, leads to attitudes and awareness among children for subjectively dealing with media, which in turn leads to their growth as a human being and as a citizen.

3. The Role of Neuvola

Kindergartens and day-care centers in Japan serve as bases for "child-raising support," and childcare practitioners are therefore expected to fulfill various roles including parent support. In contrast, the role of childcare practitioners in Finland is clearly defined as providers of "early childhood education." Meanwhile, neuvola plays a prominent role in "child-raising support." One can infer that it is effective to divide support into areas befitting the respective professions with their high levels of knowledge and skills.

Neuvola (neuvo means suggestions or advice, while la means location or place in Finnish) serves a crucial role in supporting the Finnish education system. There are several types of neuvola in line with a person's life stage, including childbirth neuvola, children neuvola, youth neuvola and family neuvola. In particular, childbirth and children neuvola are support systems targeting families with children from the pregnancy phase to preschool phase. They refer to one-stop, local bases that provide seamless support centered around a "primary care neuvola nurse" from before and after childbirth, to the child-raising phase.

I conducted a study visit to päiväkoti in March 2018. Päiväkoti is a facility formerly termed day-care center which was placed under the administrative jurisdiction of the Department for Steering of Healthcare and Social Welfare, but was renamed and placed under the jurisdiction of Ministry of Education and Culture several years ago. (Päiväkoti is a facility similar to center for early childhood education and care in Japan which serves both childcare and education functions.) This shift in jurisdiction clearly indicated that emphasis is placed on päiväkoti's role as an "educational facility." Also, since most women work full-time accompanying the progress of gender equality, all children, regardless of whether their mother works or not, are given the right to enter päiväkoti, and also guaranteed the right to receive education. At the päiväkoti I visited, children in all age groups were very calm and participated in activities in a concentrated manner. Since activities are basically carried out in small-groups, and not by the entire class as is the case in Japan, I could sense from every classroom that each child had been cherished since they were babies. What lies at the base is most likely the concept of neuvola which commences continuous support from when each child is conceived by the mother. In Japan, initiatives tend to originate from simulating risks in child-raising and considering how to avoid such risks. Whereas, in Finland, children are accepted as an independent human with social presence from the moment they are born. On site, I observed that children subjectively selected what they wanted to play and what activities they wanted to do rather than being instructed to do something by childcare practitioners, and that childcare practitioners listened calmly to children's voices. Everything was designed rationally, and the work environment was designed to be comfortable for childcare practitioners as well. For example, the height of children's chairs was the same as those for adults so that childcare practitioners need not stoop down. Nap-time beds could be stowed away in the wall to enable using ample space. In a class for younger children, childcare practitioners watched over and waited patiently while children changed their clothes before and after playing outdoors, under a physical environment arranged so that children could change on their own. Such examples demonstrate that one of the foundations supporting children's growth is a serene environment with adequate leeway for adults taking care of children.

At päiväkoti, children's growth and development are fostered systematically through "pedagogical activities," and the process and goals of their growth are shared with parents. Parents can receive support on their children's development and health based on medical knowledge through continuous dialogues with neuvola nurses, and are thereby able to raise their children with a sense of reassurance. When their children become sick, parents can ask neuvola nurses to issue prescriptions at neuvola within health centers. Furthermore, by submitting the medical certificate obtained on the spot to their workplace, parents are permitted to take leave from work. A system is in place enabling parents to readily stay by their child's side.

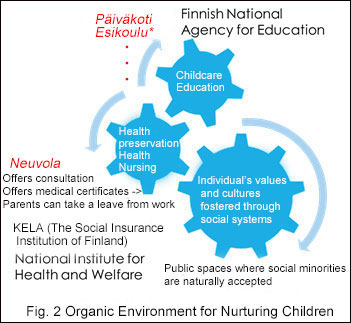

In Finland, the concept of "well-being" is persistent as a foundation of an organic environment for nurturing children, and the individual is cherished above all. This is common to children, parents, childcare practitioners and workers alike. Children's emotional skills are nurtured by the entire society through the interlocked gearwheels of society-wide values, health preservation and education (see Figure 2).

In Closing

The website of the Embassy of Finland introduces various emojis, and among them is one that stands for "sharing with each other" (see Figure 3). I felt this spirit on many occasions during my study visit in March last year. For example, when riding the VR (i.e., express train), I wanted to place my suit case on the shelf, but the lower shelf was unfortunately full and only the upper shelf had space. Seeing that I was having trouble, a female stranger tried to help me put my suit case on the top shelf, but slightly lacked strength, so she called out to another male passenger, who helped us. Furthermore, on finding out that I only had bank notes and could not pay the 0.5 euros necessary to use the locker-type shelf, the women slipped in some coins for me and said "No problem, we should help each other in times of need." Various considerations were also made in the design of trains. For example, there were train cars that allowed pet dogs (considered family members by many) and ones with play areas for children. The spirit of cherishing one another and accepting differences was exercised everywhere. I spotted many mothers and fathers pushing strollers in town, and parents could get on trams, subways and buses without folding their strollers even when the vehicle was crowded. Other passengers would take that for granted and make space. Finland is still a very young country, having marked its 100th anniversary since foundation, with a population of 5.5 million (as of January 31, 2017). As such, various things are developed rationally without complicated constraints. Against such a social backdrop, the Finnish education system differs from that of Japan in many aspects including cultural background; yet, I believe there is much to learn from their education system.

- *Esikoulu: In Finland, primary education starts from age 7. Esikoulu, which serves as a preschool or a preparation phase for learning spanning a year before entering primary school (age 6), has become part of compulsory education.

References

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), "Course of Study for Kindergarten" and "Courses of Study."

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW), "Guidelines for Nursery Care at Day Care."

- Cabinet Office, MEXT and MHLW, "Courses of Study and Childcare for Certified Centers for Early Childhood Education and Care."

- "National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014."

- "National Core Curriculum for Pre-primary Education 2014."

- "National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care 2016."

- Website of the Embassy of Finland, https://finland.fi/emoji/ (accessed February 27, 2019).

This study is sponsored by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research: JP17K04656, and expands on a poster presentation presented at the 15th Conference of Japanese Society of Child Science.

Megumi Nakamura

Megumi Nakamura