Since the birth of my daughter and her attendance at the local Japanese nursery school began, a new world of books opened up to me: the world of Japanese picture books. Though I knew many English titles from my work in English acquisitions for the relatively large picture book collection at our school, I was basically ignorant of Japanese works until Japanese friends started giving us their favorites and my daughter showed me library books that her teachers had read to her class. These tales were charming, and I was enchanted by almost all of them. However, pursuing titles at local bookstores, there was still one type of Japanese picture book that I could not understand. Not only did the words, the meaning, even the pictures defy my understanding, but I also found them so disorienting that simply to look at the pictures turned my stomach.

A contemporary, prize-winning author

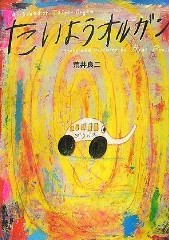

Imagine my surprise when the second keynote speaker of the International Research Society for Children's Literature (IRSCL) conference I attended was Ryoji Arai, the creator of Taiyo Orugan (literally, "Sun Music Box") and other titles, who had just received the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, a prestigious international award from Sweden that is one of the highest international recognitions for children's literature, and that also has a large cash component. Taiyo Orugan was just the sort of book that turned my stomach!

|

Taiyo Orugan, Ryoji Arai, Artone, 2007 |

The pictures looked to my eyes like a mish-mash of scribblings, and my ignorant mind could discern no meaning in them, much less a story. I was shocked that Arai had been invited to share the stage with Mr. Matsui, the fifty-year veteran of children's literature publishing in Japan whose talk is discussed in IRSCL Part I. However, since I could not understand Arai's work at all, I learned an incredible amount from his speech.

Arai began with a frank confession that he had had trouble attending elementary school for the first few years and was often truant. This is a very serious but common problem among children in Japan. However, during this period he entered his own world in picture books. In his talk he spoke of how he looked at picture books on his own, of how turning the pages and "entering different worlds" was what he loved. In replicating this feeling for readers of his own works, he was inspired by the famous work Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown, especially passages such as "Goodnight air" and "Goodnight noises". This comment gives a hint, I think, to understanding Arai's books.

Arai admitted quite readily that reactions to his first books were strongly negative. However, he said, this made him happy: "As long as the reaction was strong." Before hearing Arai's talk, looking at the pictures in his books for me was like looking at a child's very chaotic and messy drawing. In creating them he takes into account the different ways adults and children view pictures. While adults look at the middle, Arai says, "...children look at the tiny details in the picture, things that have nothing to do with the story."

Arai creates his books specifically for this audience. By his own admission, Arai's books do not contain a story and have no intent to teach. Instead, he aims to create a book children will want to look at again and again.

As an example, he talked about his book Taiyo Orugan (literally, "Sun Music Box"). His message in this work is very deep, and an important one especially for children: that there is always something watching over us. The sun represents that "big presence" while the bus that appears throughout the book is the small entity the reader is meant to identify with. The enormity of the meaning Arai communicates here is stunning: this is a book for the smallest children about faith and religion, and yet he executes it without any reference to specific doctrine. When I realized the depth of meaning he had created in this work, I was completely shocked. It is very easy to dismiss these books out of hand because of their "messy" pages, but when we do so we show only our own ignorance.

Arai also talked about the workshops that he does for children. For three and four year olds, these workshops are about creating something immediately in that place and time. In a workshop titled simply "Laundry," he had participants dip several hundred pieces of oddly shaped cloth in various buckets of colored dye and then hang them on a hundred-foot clothesline. Some kids stuck their hands in the dye. Some played under the flapping "laundry". In another workshop called "Drawing Music," participants painted a grand piano with their hands and "drew" a piece of music which a pianist then played. Of his workshops, Arai said that they have no purpose such as "teaching". If adults asked him at the end, "What did you do?" he said simply that if they didn't get it, he couldn't answer.

At the end of his talk, he spoke about making a picture book like a modern e-maki, the long picture scrolls that were the "books" of Japan centuries ago. It seemed fitting, as Mr. Matsui talked about these as the beginning of children's literature in the first keynote speech (see Part I). Arai also spoke of how he hoped his picture books were like a window for his readers. He certainly opened a window for me and taught me how to appreciate these works of which I had been so ignorantly critical.

Recent problems in children's literature

Talks during the afternoon and remaining four days of the 18th Biennial Congress of the International Research Society for Children's Literature ran simultaneously at multiple venues on a vast array of topics relating to children's literature. However, one of the most alarming topics, mentioned by a number of researchers, was on trends of globalization and the commercialization of children's literature. Naomi Asagi gave an entire talk on "The Americanization of Picture Books in Japan" and the related "diminishing" of Japanese culture. Elizabeth Bullen talked about "Consumption and Class Identity" in young adult literature. Still others touched on changing expectations for profit margins among publishers in Japan and the U.S. as well as other countries, and trends like product placement - essentially advertising commercial goods - in novels for young adults.

While it would have been physically impossible to attend even a quarter of the fascinating offerings since several talks were being given in different rooms at any one time, one of the most informative and shocking talks on this topic that I attended was given by Joel Taxel from the Language and Literature Education Department at the University of Georgia. Taxel's talk was titled "The Commodification of Children's Literature in the 21st Century: Sequels, Series, and Synergy." He used the word "synergy" to refer to interconnected aspects of marketing a book.

Focusing on profits

Taxel began with the alarming statistic that eighty percent of U.S. publishing is controlled by only five conglomerate corporate entities. America has always been wary of monopolies or too much control by too few bodies in any industry because of the lack of freedom (competition that sets fair prices, etc.) that it implies. However, the trend is frightening in an industry like publishing because here the commodity is information. Too much control of the flow of information by too few people - and a possible resulting lack of freedom of information - could be very dangerous, especially in our so-called "Information Age".

Taxel went on to describe how this amassing of power in the hands of a few has fundamentally changed the publishing industry: now, according to Taxel, the first priority of the company owners is that of making money and as much of it as possible. For comparison, he told us that the historical profit returns on books was four percent after taxes. Now, however, these companies expect returns of three to five times that much. Traditionally the decision to publish or kill a book was made by people with a background in literature. Now, however, Taxel says that these decisions are being made by those with educations in marketing and business.

Ramifications and the future

If Taxel is right, these trends will cause children's literature, and thus children's introduction to the written word, to change completely as we know it. How will this affect the education, culture, and values of coming generations? How will it change American culture, and thus other countries worldwide that are becoming "Americanized" as one speaker said was happening to Japanese children's literature?

Yet as Mr. Matsui pointed out (see Part I), we do have the classics of children's literature in both languages, and doubtless they will endure. It is a shame, however, that our generation will be able to leave little for posterity besides thinly disguised commercials. Perhaps works like those of Arai's will speak directly to children, assuming of course that such books manage to make it into their little hands.

(Mr. Matsui and Mr. Arai's speeches were given in Japanese. Translations are my own and I take full responsibility for any mistakes.)