Bilingualism and Language Teaching Series

- 1. Bilingualism as the Goal of Language Learning (This paper)

- 2. How Bilingualism Informs Language Teaching

Introduction to this article

The discipline of bilingualism in applied linguistics is the study of different languages that come into contact at various levels in the same social space or person. Active bilingualism research groups in Japan show, on the one hand, a fascination with an idealized view of dual language proficiency that is virtually out of reach as a goal. On the other hand, bilingualism principles (McCarty, 2010b) and worldwide research findings serve the imperative of international families to raise well-adjusted bilingual children (McCarty, 2010a). This article aims to clarify the various meanings of bilingualism, and to show how understanding bilingualism developmentally makes it a realistic and appropriate goal of language learning.

Meanings of "Bilingualism"

The word "bilingualism" can mean many things, which together form a "perspective" on language issues and life decisions. Becoming bilingual oneself, it becomes possible to see the same event from the standpoint of two different languages and cultural viewpoints. Changing from being monolingual as a child to becoming bilingual as a language teacher also makes it possible to see that, developmentally, bilingualism is the proper "goal of second and foreign language education" (McCarty, 1992, p. 3).

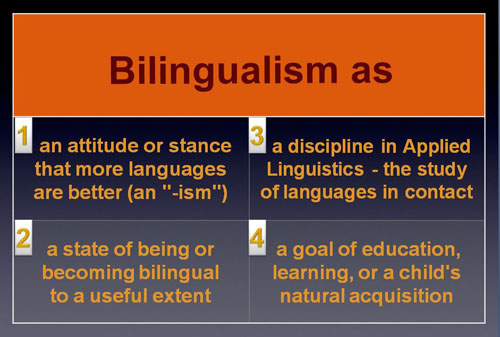

To gain a fuller understanding of bilingualism as a perspective, consider some of the meanings people can have in mind when they use the word:

- Bilingualism as an "-ism" refers to an attitude or stance, usually based on positive intercultural experiences, that having two languages is better than one for people generally. Bilingualism includes multilingualism, so three languages are considered better than two, and so forth. Monolingual and monocultural people often simply lack intercultural experiences, but their attitude becomes an -ism, monolingualism and monoculturalism, when they are taught to exclude from humane consideration others who are different from their group. Therefore, from this perspective, bilingualism is generally better morally, ethically, and humanistically. For instance, tolerant and broad-minded peacemakers are more likely to arise from among those with a bilingual and bicultural perspective.

- Bilingualism as an -ism can be operative at different levels, including individual experience, bilingual child-raising in the family, bilingual education in schools, or government policies in some countries. At the individual level, however, bilingualism often implies a measure of the extent to which a person is bilingual or proficient in a second language. Bilingualism in this sense refers to a state of being or becoming bilingual to a useful extent, where functioning in two languages or more makes a difference in an individual's life or way of thinking. Particularly when considering bilingualism in this sense as a goal of education, it will be important to see bilingualism realistically as a matter of degree. Balanced bilinguals are rare, and dual native speaker ability is not necessary, because people use different languages in different domains for different purposes. The measure of bilingualism should be the individual's needs.

It can be awkward to use the terms bilingualism and biculturalism to describe how bilingual and bicultural a person is, so the technical terms "bilinguality" and "biculturality" are sometimes used for that purpose. Derived from French, "bilinguality is the psychological state of an individual who has access to more than one linguistic code as a means of social communication" (Hamers & Blanc, 2000, p. 6). "Bilingualism" is often used in this sense. - Bilingualism is also a discipline in applied linguistics, the study of languages in contact, within and between individuals and groups, and at different levels. This meaning of bilingualism will be detailed in the last article of this series.

- A fourth meaning of bilingualism is as an explicit or implicit goal of education, learning, or a child's natural acquisition. It can be an aim for bilingual functioning that may be stated or implied in the literature of bilingual or international schools. Also for individuals who are not bilingual yet, it is an imagined future state to aim for. Children of international or intercultural marriages, raised from age zero hearing two languages, may to some extent have two native languages, especially if that was the intention or goal of their parents. This highlights the fact that, in schools as well, bilingual functioning is more likely to be the outcome if, informed by the field of bilingualism, it is established as an attainable goal.

Reviewing the above chart then, bilingualism is a stance, a state, and a field. It is a goal, a means toward that end (bilingual education), and a perspective on the whole process.

Bilingualism as the Goal of Language Learning

Bilingualism as a goal has been introduced, but further clarification is needed to show how bilingualism can be an attainable goal. Bilingualism has been overly idealized in Japan (McCarty, 2010a), an unrealistic image of two native speakers in one person. Such an unattainable ideal cannot serve as a goal. Rather it discourages language learners like a nearly impossible perfect score by a non-native speaker on a TOEIC or TOEFL test. Those who are actually functioning bilingually hesitate to admit to being bilingual, afraid that it sounds boastful. Those who are not functioning bilingually yet are liable to give up because the idealized image is completely out of their purview. It becomes someone else's business, an excuse not to make progress in a second language, or at best a curiosity. Rather, the bilingualism referred to here as the goal is simply bilingual functioning according to the needs of the individual. The goal is for people to be able to use two or more languages naturally in their life, so that language is not an obstacle, in order to fulfill their chosen purposes. People are always learning new vocabulary and expressions even in their native languages, so bilingualism will always be a matter of degree. The bilingualism to aim for is, as the above chart indicated, a state of being bilingual to a useful extent.

It may seem self-evident that the goal of language learning is to master the second language (L2) as much as possible. But there are some exceptions and problems with this assumption. In social circumstances where the native language of an immigrant or minority group is not valued (Vaipae, 2000), the unequivocal pursuit of L2 mastery can lead to the replacement of their native language by an incomplete second language, which is called subtractive bilingualism (Baker, 2006, p. 74). More can be lost cognitively than gained in such cases, so native languages should, and can, be maintained while further languages are acquired. People who have free choice of languages usually enjoy the cognitive benefits of additive bilingualism, where there is only enrichment and nothing is lost. Therefore the goal is not the one-sided pursuit of another language but rather balanced bilingualism, in the sense of maintaining native-level languages while developing weaker languages by regular use.

Even native-speaking language teachers have not upheld bilingualism as the goal of language learning or L2 acquisition. The native speaker model of 'correct' pronunciation and so forth, held up as the implicit aim, reinforced by standardized tests, is the counterpart of the overly idealized image held by non-native speakers like the Japanese. They suspect that if they did not start speaking English or another second language in childhood, they are condemned to never have native-like pronunciation. Research shows that children must start a second language by age eight (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, p. 138) if native-like pronunciation is a goal. Therefore, if they or their children have passed age eight already, the native speaker model should not be held up as a goal. Implausible or overly idealized goals like the native speaker model demotivate and disengage students from realistic goals.

Each person has a developmental path, in language as in other areas of psychological growth, and each person has different needs, which may change at different stages of life. The individual may well respond voluntarily to the needs of society for proficient users of international or bridge languages for international trade and so forth. But standardized foreign language proficiency tests, and extrinsic norms in general, imposed by others, disregarding the whole person and the social context, are fundamentally misguided. The standard should rather be the individual's developmental path and needs. Learning is a process of organic growth, which can only move from what the individual actually is to what the individual is able to grow into. Depending on the needs and purposes of the individuals, a reasonable goal of bilingual functioning is within reach.

-

References

- Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (4th ed.). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Golinkoff, R.M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2000). How babies talk. New York: Plume.

- Hamers, J.F. & Blanc, M.H.A. (2000). Bilinguality and bilingualism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- McCarty, S. (2010a). Bilingualism concepts and viewpoints. Tokyo: Child Research Net - Research Papers. Retrieved from

- McCarty, S. (2010b). Bilingual child-raising possibilities in Japan. Tokyo: Child Research Net - Research Papers. Retrieved from

- McCarty, S. (1992). The bilingual perspective. The Language Teacher, 16 (5), 3.

- Vaipae, S.S. (2001). Language minority students in Japanese public schools. In M.G. Noguchi & S. Fotos (Eds.), Studies in Japanese bilingualism (pp. 184-233). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.